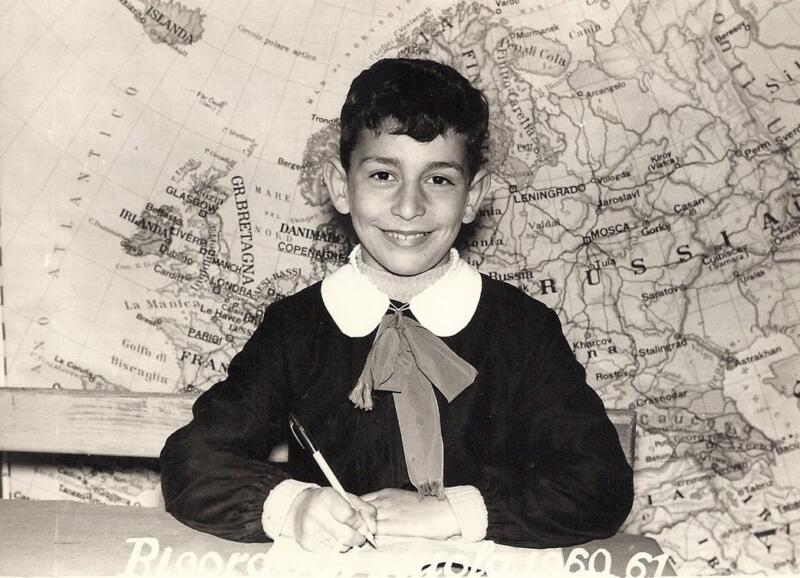

1670 An Italian childhood

Mea Culpa: A Plea of Innocence. A Memoir

by Bruno Cocorocchio

Victoria: FriesenPress, 2022

$24.49 / 9781039137462

Reviewed by Jane Frankish

*

The title of Bruno Cocorocchio’s memoir, Mea Culpa: A Plea of Innocence, has an immediate and jarring effect. It sets up a seemingly impossible concurrence of two states of being – “I am guilty” and “I am innocent.” I know that “mea culpa” is an exclamation acknowledging one’s responsibility for an error.[1] Nevertheless, I am compelled to look further into its origins, and I find that it is part of the Catholic prayer, known as the Confiteor:

The title of Bruno Cocorocchio’s memoir, Mea Culpa: A Plea of Innocence, has an immediate and jarring effect. It sets up a seemingly impossible concurrence of two states of being – “I am guilty” and “I am innocent.” I know that “mea culpa” is an exclamation acknowledging one’s responsibility for an error.[1] Nevertheless, I am compelled to look further into its origins, and I find that it is part of the Catholic prayer, known as the Confiteor:

mea culpa, mea culpa,

mea máxima culpa.

through my fault, through my fault,

through my most grievous fault;[2]

The recital of the Confiteor is often accompanied by a banging of the chest, signifying great sorrow for things done, or not done, and an unworthiness in the sight of god.

“And all the people that came together to that sight, beholding the things which were done, smote their breasts, and returned” (Luke 23:48).[3]

The Confiteor is often recited by altar boys when they learn to perform mass, and the young Bruno was an “accomplished and well-liked Altar boy” (p. 71). While “Mea culpa” alludes to a specifically Catholic sense of guilt, this memoir explores the more personal sense in which we all feel deep sorrow, sadness and shame in our lives.

I am equally intrigued by the subtitle of the memoir, A Plea of Innocence, which seems to reach out to the reader to ask for a reconsideration of blame. It is a plea from the accused, the opposite of Mea Culpa! At the beginning of his memoir, Cocorocchio makes a disclaimer about “truth.” It seems that for him, truth, like beauty, arises in the senses and is subjective. He asks the reader to understand that one person’s truth may not be true for another. He says that his memoir “is a record of childhood experiences that created triggers in my adult life” (front matter).

I begin to hear a clash of truths. The adult writes and records what is remembered by the boy. The memoir is filled with stirring impressions of sorrow and pain, but is this how it happened? Is the author responsible for transmitting the truth of the child or the truth of his adult inquiry?

Might these be different? Is this memoir less about what may or may not have happened to the child, and more about sharing the adult’s reunion with the hurt child inside himself?

The book begins with an essay that Cocorocchio wrote when he was twelve years old. It is an assignment for school, in which he presented a person whom he was particularly fond of. Bruno wrote about his mother, “her name is Elena, she is tall and the color of her eyes and hair is chestnut” (Introduction, p. xiii). He describes her as someone who “prefers to stay at home from morning until night rather than go out to have fun” (Introduction, p. xiii). This earnest effort earned the boy a C-. I imagine the casual indifference of the teacher who stamped this evaluation on the essay, and I begin to see how the adults surrounding Bruno shaped his story.

Cocorocchio goes on to present a series of vignettes set in a small village near Rome. Sant’Elia Fiumerapido is home to all the folk who are somehow implicated in causing hurt in the life of this young Italian boy. Cocorocchio’s mother is described in the first chapter as, L’Addolorata — Mother of Sorrows. She is full of sadness, “growing up in a war-torn country, Mamma experienced famine and poverty from a very young age” (p.1). Papa is a tailor and works in his brother’s shop. He constantly argues with Mamma about money and his position in society. Mama sees Papa as a man with no prospects. They appear to be in an endless argument, which dominates Bruno’s young life and becomes the backdrop to this memoir. He takes the blame for the pain and much more besides, “It’s my fault that they’re poor” (p. 11).

As a young boy, Cocorocchio was often locked in his parents’ apartment or left alone at the back of the tailor shop. It is on one of these occasions that we first come across the figure of the centurion — in the shape of a button! Bruno’s father has given him buttons from the tailor shop, and out of these, the boy creates imaginary armies. He categorizes the buttons. The small buttons are foot soldiers and the larger buttons are commanders. There is one unique button that does not fit in with the rest, “It’s not round like all the others but square” (p.18). This button is fantastical. It has a combination of colours and gold on the corners. This button becomes the Roman centurion. As Bruno exclaims, “He is everything I wish I could be” (p.18). Bruno has created an imaginary champion. The centurion becomes a trusted comrade, and the button, a place from which to gather strength — to imagine striking back, when in fact he has no means of coping.

In the chapter, Pasta e Baccala — Pasta with Salted Cod, Bruno’s trauma is fully realized. In class, he reads the story of Muzio Scevola who fails in his mission to kill the invading Etruscan King. When questioned before the king, this brave Roman puts his hand in a nearby fire until it burns right off. The king is so impressed that he ends the war and returns home. Bruno imagines both this heroic action and the pain of the burning hand. This helps him get through the awful incident over the salted cod meal, when his Mama assaulted him with closed fists. Bruno accepts the pain. He deserves it, “I must be punished … for I have failed … I must pay … I can endure the pain … yes, I can … am I not Muzio Scevola, cittadino di Roma?!” (p. 39).

Danger lurks around every corner for the young boy. There is Zio Ettore, a young uncle who rubs up against him as he looks out the window. Zio Ettore “pushes up against me. Back and forth. Harder, Faster, I want him to stop” (p. 44). The young Bruno finds himself in an unbearable situation, an unthinkable position. In the trauma of the moment, he becomes the centurion, “I must endure … because I am a centurion … from the hilltop I access the legions … they are well-rested and well-fed … they are ready for battle … we will win … I will lead them to victory!” (p. 44).

Mea Culpa records many memories of family and village life, some good, others traumatic, and then, when Bruno is about twelve years of age, the family emigrates to Canada. Cocorocchio describes his first steps on Canadian soil and exclaims in capitals and italics, I KNOW WHY CRISTOFORO COLUMBO KISSED THE GROUND WHEN he got off the Santa Maria in 1492. He was seasick just like me!” (p. 93). This seems to be a point of transition. Bruno leaves the imagined Roman centurion of his childhood behind. He is now an explorer in his own right. The boy becomes a man in Canada, and has his own set of experiences, independent of his Italian parents.

The memoir goes on to present the familiar dilemma of immigration — assimilation into the new country versus yearning for the old one. After thirty seven years in Canada, Cocorocchio’s parents return to Italy for their retirement. Cocorocchio’s father passes without fully acknowledging his son. At the funeral he finds himself wondering, “what it would feel like to be in a coffin while it was being interred.” This image reminds me of Muzio Scevola’s hand in the fire. Cocorocchio then reveals his deepest fear and his hope, “Surely, there is salvation for people like us” (p. 180).

In the final chapter, Figlio di Mamma — Mama’s Boy — Cocorocchio is at his mother’s bedside in an Italian nursing home. Building on the childhood memory of salt cod, Cocorocchio turns to gagging imagery to express his painful bond with his Mamma. “I have swallowed a fish hook, and it remains lodged in my throat” (p.191). Cocorocchio’s final words in his memoir are, “She continues to suffer. In me. Mea culpa” (p. 192).

The mother’s suffering is trapped inside of the son. The pain of Cocorocchio’s guilty plea seems, in itself, evidence of his innocence. In the Postscript, Peter DeRoche, a psychiatrist at the University of Toronto, says, “Bruno had no choice but to learn resilience from an early age. He put it to good use, but paid a high price. He accepted the pain despite his continued efforts to uncover its source” (p. 196).

I feel the resilience in Cocorocchio’s memoir, standing as courageous as a Roman Centurion on a hilltop, waiting for the onslaught of memory.

*

Jane Frankish is a writer of poetry and prose. She holds a Master’s Degree in Liberal Studies from SFU, a Masters in Library and Information Studies from UBC, and works as a librarian at Vancouver Public Library. Editor’s note: Jane Frankish has also reviewed books by Eileen Casey & Jeanne Cannizzo and Jenny Boychuk for The British Columbia Review. She has also published a popular memoir, Chennai: A Place in Between, and a Letter from the Pandemic, in The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] “mea culpa, int. and n.”. OED Online. September 2022. Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/115382?rskey=AhaePG&result=1&isAdvanced=false (accessed November 16, 2022).

[2] https://www.saintanneshelper.com/confiteor.html (accessed November 16 2022)

[3] https://www.kingjamesbibleonline.org/Luke-23-48/ (accessed November 16 2022)

2 comments on “1670 An Italian childhood”