1654 Chilcotin master chronicler

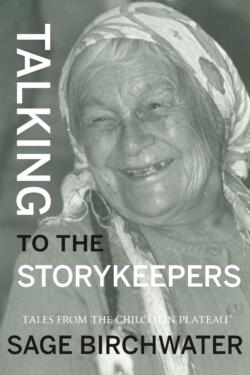

Talking to the Storykeepers: Tales from the Chilcotin Plateau

by Sage Birchwater

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, 2022

$26.00 / 9781773860800

Reviewed by Richard T. Wright

*

The Cariboo-Chilcotin-Coast region in the central-west portion of the province of BC is a land renowned for broad grasslands, magnificent mountains, fast glacial rivers, salmon, caribou, vast cattle ranches, and Indigenous court challenges.

The Cariboo-Chilcotin-Coast region in the central-west portion of the province of BC is a land renowned for broad grasslands, magnificent mountains, fast glacial rivers, salmon, caribou, vast cattle ranches, and Indigenous court challenges.

The land and its people have spawned many books, from Leland Stowe’s Caruso of Lonesome Lake (1957), Cliff Kopas’s Bella Coola (1970), Paul St. Pierre’s Breaking Smith’s Quarter Horse (1966) and Boss of the Namko Drive (1969) and his newspaper columns and CBC fictional shows, as well as Irene Stangoe’s Looking Back at the Cariboo-Chilcotin (1997) and History and Happenings in the Cariboo-Chilcotin (2000). To these must be added the impressive output of author and journalist Sage Birchwater, including his classic book Chiwid (New Star Books, 1995), and his recent Chilcotin Chronicles: Stories of Adventure and Intrigue from British Columbia’s Central Interior (Caitlin Press, 2017) [Reviewed by Lorraine Weir – Ed].

In Talking to the Storykeepers: Tales from the Chilcotin Plateau, Birchwater has penned perhaps his best yet. What is more, arguably no one else could have woven this colourful tapestry of stories.

For background: in the early 1970s Rick Stamford dropped out of the University of Victoria to travel. In his words, in 1975 he and his partner “disappeared into the mountains to reinvent the wheel and rediscover fire on our remote trap line in the Chilcotin, and when we reemerged in the spring we were Sage and Yarrow.”

He spent the next 24 years in a variety of jobs and adventures in the broadly-based Chilcotin. Then in 2001 he became a Williams Lake Tribune reporter. This background is important. His life not only put him in touch with the people of the west, including Indigenous people and ranchers, but earned him hard-won credibility and respect, attributes that gave him access to the stories recounted here.

During his career as a journalist, Sage Birchwater wrote about many of the people introduced in Talking to the Storykeepers, and a fan of his work will detect a bit of overlap in the tales. But they are great tales, tales that deserve to be told again, and which moreover can tell us where some of the current cultural connections and separations originate. Sage has rare insight into the culture of the Chilcotin. By being in some cases the chosen scribe for First Nations events, he became part of the stories, which now he generously shares with readers.

Local history is often used as a pejorative term, but Sage has the gift of transcending the local to provide the collective history of a people, and of documenting a time that is quickly passing. In the process he makes his readers a part of the land.

Full disclosure: I have lived half my life in this same country as Sage Birchwater and have heard oral versions of some his tales, and he and I have crossed paths on occasions. I can say I envy Sage for his connections, hard-won though they are, and for his ability to transcribe these tales. He makes us wish we knew the folks he is writing about.

The introduction, which explains in brief the background of BC, is to a certain extent autobiographical. As the chapters unfold, Talking to the Storykeepers: Tales from the Chilcotin Plateau narrows in focus and becomes the recent history of the Chilcotin and Williams Lake areas – from the first Indigenous encounters with Alexander Mackenzie, to the settler period of the 1930s, through to the hippy commune era, and finally to those folks still on the land.

These are stories hard to imagine today, for example a life saved when a flour sack is used for blood stop; of working for eight years without pay; of birthrights denied by baptisms; of horses’ ears and horsetails, of desperate races for medical aid, of salmon and suckers, potatoes and creation myths, all wrapped and seasoned in the myths from thousands of years, yet as fresh as the accounts of the depression and the hippy era. We are invited to attend birthdays, funerals, food gathering, and harvest celebrations as if we were members of the family. Talking to the Storykeepers is a valuable source of story, lore, biographies, and background. It should be required reading for BC residents.

There is also wisdom here, for instance when Emily Lulua Ekks says, “Don’t keep going to places you don’t belong. Doing that isn’t good for you. Stay close to home and teach your children the proper way to live.”

Woven into the stories Sage documents a semi-nomadic, self-sufficient people being forced onto reserves and built communities and their children taken to the now familiar residential schools. There is forgiveness when Nuxalk Chief Councillor Archie Pootlass, speaking at the final blessing of the Bella Coola Emmanuel United Church, says, “I have a lot of painful memories from attending school. Now it is time for me to forgive the United Church for managing and administering that Facility.”

If I can find a fault with this fine book it rests with editorial decisions. The book, and the stories themselves, suffer from the lack of a map or, preferably, maps. If you have bounced around the Cariboo Chilcotin for as many years as I have, you will know where Anahim, Bella Coola, the Dean River, Towdystan, and Redstone are. But it takes a local to understand Borland Meadow, Bidwell, Cless Pocket Ranch, the route of the Nuxalk-Daketh Grease Trail, Henry’s Crossing, Stuie, and others.

Birchwater’s stories draw us in, and we want to grab a map and follow the seasonal migrations of so many rich characters. The language and telling is overflowing and a map would have helped situate this regional abundance.

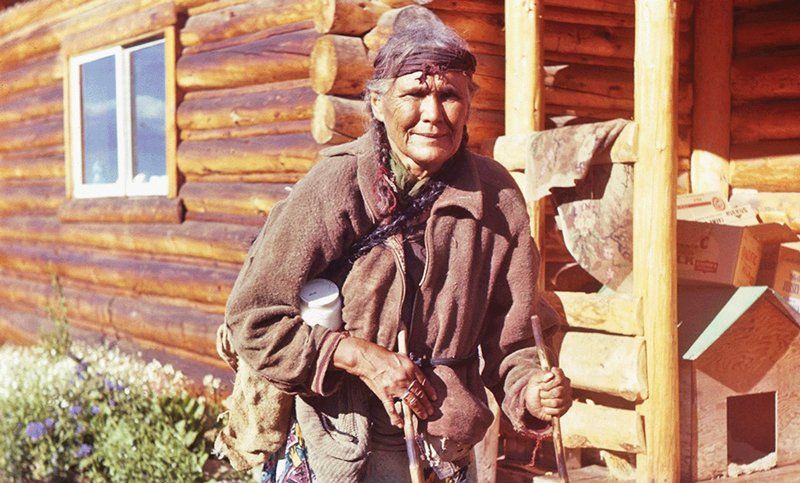

Talking to the Storykeepers is filled with photos and, while one could argue with the layout and quality of some, they serve to help tell the stories in a visual sense.

These are the stories heard in Cariboo Chilcotin cafes and corrals, stories that drift through the trees and across hay meadows like smoke from ancient campfires. Sage Birchwater deftly fans those story embers to life, bringing warmth and light to a new generation. These are stories that ought not die.

*

Richard Thomas Wright is a British Columbian environmental and history writer and photographer, a playwright and filmmaker. He has written 22 books, a dozen plays and produced some 40 films. With a particular interest in the BC goldrush, Wright’s Barkerville and the Cariboo Goldfields (Heritage House) is now in its 5th edition (2013). He is also author of The Overlanders (1985), a study of the gold seekers who travelled the land route to the gold fields. As a revisionist historian he produced two treks with camels, deconstructing the “Cariboo Camel” myth for segments on National Geographic Today and On The Road, CBC, and has collected BC folksongs for two music CDs. In 2004 he and partner Amy Newman contracted to run the Theatre Royal in Barkerville, where he produced, directed, and wrote ten plays including The Unquiet Grave, Westering Man, and Diller’s Luck. During this time he and Newman began the Bonepicker.ca project, a film series on Vimeo that “picks at the bones of history.” Several of his films have won international awards. In 2019 Newman and Wright left Barkerville and the Theatre Royal for other projects. Wright is a consultant on “art in heritage” issues and leads the Cariboo Waggon Road Restoration Project for the New Pathways to Gold Society. See his work also at Winter Quarters Productions.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

8 comments on “1654 Chilcotin master chronicler”

We lived in the Chilcotin for over 30 years (27 of that in a wilderness valley) and still miss that wonderful and special place. Your review brings to life Sage’s approach and content, and we’re eager to read his latest book as everything he writes about that country is always authentic and fascinating.

Aw, thanks dear hearts. So looking forward to reading your brand new memoir of that place.