1603 Writing to shape one’s future

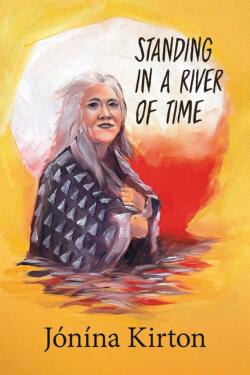

Standing in a River of Time

by Jónína Kirton

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2022

$19.95 / 9781772013795

Reviewed by Cathy Ford

*

If, when you begin reading, and then rereading, a book by this author, soon after the second anniversary of National Truth and Reconciliation Day in Canada, perhaps you should know already your life will change. That is, a kind of celebration is occurring in these pages, written before and through the sorrowful, full awakening to comprehension of the trials and traumas undeniably apparent to every conscious Canadian, as suffered by Indigenous and Métis peoples, through colonization, through the residential school system, through intergenerational pain and remembrance. And yet, here is a writer who has faced these issues in her own life, her own family, her own healing, and is not only searching out a healing path, but giving guidance to the rest of us, especially those opening a book avowedly full of poetry.

If, when you begin reading, and then rereading, a book by this author, soon after the second anniversary of National Truth and Reconciliation Day in Canada, perhaps you should know already your life will change. That is, a kind of celebration is occurring in these pages, written before and through the sorrowful, full awakening to comprehension of the trials and traumas undeniably apparent to every conscious Canadian, as suffered by Indigenous and Métis peoples, through colonization, through the residential school system, through intergenerational pain and remembrance. And yet, here is a writer who has faced these issues in her own life, her own family, her own healing, and is not only searching out a healing path, but giving guidance to the rest of us, especially those opening a book avowedly full of poetry.

This book is fully weighted with a serious poetic intelligence, a push toward narrative, detail, image and metaphor that gifts the reader with an understanding of a unique life, and the places in that life, and in these poems, that reach commonality, reverb. The collection also contains a kind of interpersonal conversational prose that can’t quite be entirely memoir, or entirely that doppelgänger “creative non-fiction,” or entirely fiction, such care is taken with each consideration of experience along the way. Some of the details of Jónína Kirton’s life facts, observations, sufferings as experience, are heart-rending, stark in the clarity of the telling. Some details are introduced with care and consideration, and the harsher elements more subtly rendered.

In Standing In A River Of Time, this juxtaposition between the creation of poetry, and the retelling of recalled life experience side by side in prose makes a convincing argument for those all-too familiar notions that both writer and reader should examine the quality of an author’s intent, the old “write what you know” test, truth-telling, and other critical swerves. Yet, here is an example, self-identified, the manufacture of open invitation and grace-filled consent, to stay with a writer sure of her ground, realizing the importance here, of weaving together the sparks of experience, the orality of the poetry, the story of the life. This is the kind of sharing from an author rarely encountered except in the most intimate of lyrical poetics, made metaphor, or almost inadvertently, behind the cloak of fictionalized story presentation. Why does this matter, what matters about this conversation between forms, between re-telling, and re-creating?

As a reader, in Standing In A River Of Time, you can see the writer at work. Not just because you are a smart reader, with plenty of poetry or other personalized written work in your ken, but because this author has decided to share her methodology, the self-education she sought, the paths she found previously unmarked, the perseverance she clung to, and the way she saved her own life. The choices made, subject by subject, event by event. Sometimes the poems are conclusive remarks, sometimes the prose is more like an argument with an old friend – the kind who listens, doesn’t just hear when the difference in lives is told. Sometimes this writer is talking to herself, reminding her own writing and her own “history” what choices she made along the way, including searching spiritual ways or courses of action.

As a reader, you have been placed by this author in a position of trust, even privilege, while she recounts the struggles in her life, her family, her journey toward self-healing, self-acknowledgement, self-appreciation. Like many who are writing as her contemporaries, Jonina Kirton as an author has ancestors who were both first people, whose lives intersected with new immigrants, and those who made new lives and communities. Not coincidently, those ancestors now found, whose resilience inherited from parents and grandparents came at cost, and whose stories had to be searched out, have been found again. This too, is a working method to know one’s history, one’s self, to shape one’s conduct, integrity, life, and lifework.

To suffer such sorrow as a family, her “mother’s tears flooding / all the rooms of our home / now we were all drowning” (from “Seekers,” p. 14), draws the line between losing two children in a family, then one’s mother too, all these sorrows interconnected. Then, in “Displaced: It’s Always About The Land” (p. 38), the end-lines move into poetic form – “Every time someone died, we moved.” Kirton writes poems for her lost brothers and reflects on the effect of such loss on having a son of her own. She wrenches understanding of her parents out of her own troubles, and looks back with a generosity of spirit that includes courage in its loving. She writes poetry as the bereaved, at the dying of her nephew who has been like an adopted stepson, his a final tragic passing in his own family, and painting dark shadows on her continually evolving personal relationships. She writes in particular of men she has made her life with, of women who have helped her find confidence in her writing talents and voice, those women who also write from the body, the body of their lives and their stories. She writes about finding the Icelandic part of her heritage, dealing with unforgettable loss, and carrying forward with a way to accept, understand, forgive.

From the section of the book, “Forgiveness: It’s Never Too Late” in the poem, “Tumbling” (p. 199), Kirton writes: “I have been carrying the dead my whole life / I had to let them go.” Having done them all justice, one can also see, as a reader. And finally, “Within The Echoes Of Erasure” (p. 201), that assurance, “You can create new pathways, tell new stories. / Rewriting reality your best defence.” Jónína Kirton is a poet and author of fresh, forthright intellect and remarkable compassion, whose ideas shape the forms she is writing in, and whose writings are shaping the future. Read this book. It’s a rare gift.

*

Cathy Ford is a poet, fictioniste, and memoirist, working predominantly on the long poem, feminist issues, life and death concerns, social justice and peace, our relationship with this beloved earth. She has published more than fifteen books, including the art of breathing underwater (Mother Tongue, 2010), and Flowers We Will Never Know The Names Of (Mother Tongue, 2014) — an abc book of the language of flowers and their transliteration, an interpretation of grief and protest, based on the Montreal Massacre. Her earlier books are published by blewointment press, Caitlin Press, Harbour Publishing, and Véhicule Press. She lives in Sidney. Editor’s note: Cathy Ford has also reviewed a book by Linda Rogers for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “1603 Writing to shape one’s future”