1598 All together now

Namwayut: We Are All One. A Pathway to Reconciliation

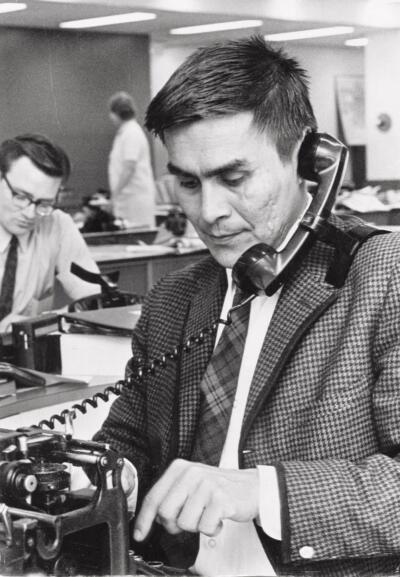

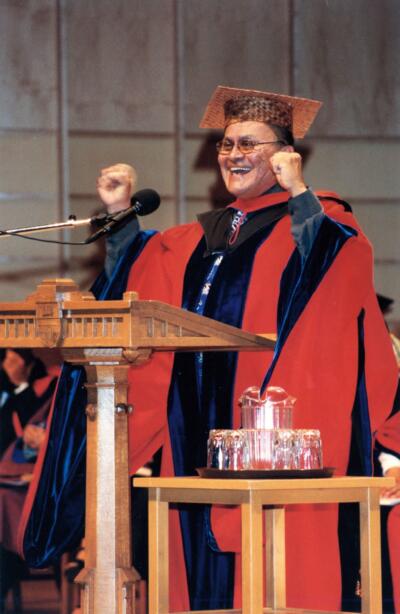

by Chief Robert Joseph

Vancouver: Page Two Books, 2022

$29.95 / 9781774580059

Reviewed by Linda Rogers

*

At last, the building, its outline terrorizing The Bay or Yalis, the community framed by open legs, both sides of the water which feeds the people, has come down. St. Michael’s Residential School aka child prison run with the collusion of the Canadian Government, the RCMP and the Anglican Church is now dust, but the horror remains in the minds and hearts of its survivors, of which the author, Hereditary Chief of the Gwawaenuk First Nation, international peacebuilder, and honorary witness to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, is one.

At last, the building, its outline terrorizing The Bay or Yalis, the community framed by open legs, both sides of the water which feeds the people, has come down. St. Michael’s Residential School aka child prison run with the collusion of the Canadian Government, the RCMP and the Anglican Church is now dust, but the horror remains in the minds and hearts of its survivors, of which the author, Hereditary Chief of the Gwawaenuk First Nation, international peacebuilder, and honorary witness to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, is one.

One is the operative word because, in spite of every effort to erase his Indigeneity, Chief Joseph holds on to his ancient credo, which should inform every believer who accepts the notion of human family, that we are all related, every living thing from the planet itself to the microorganisms that feed the sea.

That is, in the end, what allows forgiveness as we move to correct the mistakes of hubris and greed that have defined the fall of man within the construct of corrupt institutions and belief systems.

By revealing the triumphs and challenges of his own life, defining the forces of good and evil that separated him from family and culture and brought him back full circle to traditional knowledge and the defining principle of kindness, he creates a map for reconciliation with the self, the family and the larger community of humanity.

Anyone who has heard elders speak in Big Houses across his Nation and others recognises the eloquence of a leader who knows whereof he speaks. Having experienced degradation at school, addiction, loss of family and respect, he has brought himself back to the pinnacle of oration, informing others of his peril and the reclamation of his identity.

As the pendulum swings with the exhumation of child victims, many writers have walked through open doors to witness for their suffering, but Joseph, almost uniquely, rises above justified rage to show us the other side of pain. Namwayut is the map of reconciliation as we follow his path from underserved child to acclaimed adult, robed in the glorious raiment of his Kwakwaka’wakw ceremonial regalia.

There are others, lost in bitterness and newly discovered ambition, who turn from universal brotherhood and sisterhood and deny the opportunity to smudge the past and build a future out of the ashes of degradation. But not the author of Namwayat, who fully understands the desideratum of his people: We are One.

There will be a Renaissance and we will share it. It is starting to happen and action comes out of the cursed memory of schools like St. Michael’s, Kuper Island, Port Alberni and dozens of others that were designed to take the Indian out of the child, to deny the integrity of birthright and instil the competitive principles of capitalism.

It will take all of us to rebuild and it is leaders like Chief Joseph who know the steps to personal and social salvation, world harmony, no more othering.

That this testament comes from a child who was kidnapped by the forces of evil, taken from his protector, his beloved Ada, and abused body and spirit is nothing short of miraculous reconnection with the Creator who turned from him when most needed. Joseph does not spare details as we live the horror of porridge filled with worms and cruel disciplinarians

who preach godliness and desecrate the precious bodies of children.

On a personal note, my boys grew up in Cowichan alongside children who reflected generational trauma, parents and siblings taken by Kuper Island which we knew to be a penal colony of innocents. But they never told of the deep wounding when we asked the kids what hurt when they fell down or cried. They had been threatened into silence like young scholar and athlete Richard Thomas, who was hanged at Kuper Island, now Penelekut Island, and accused of suicide for threatening to tell about the abuses he witnessed and endured.

My first recollection of telling was an elder who broke down on the water taxi to Yalis on Cormorant Island, site of Joseph’s stolen innocence, the day of Henry Hunt’s picture dance, almost a decade after most infant prisons were shut down. Triggered by the shadow of the school on the water, he began his transformation from victim to survivor. Everything Joseph writes is affirmed by the experience of many, many young people.

That Joseph tells of his humiliation in detail is courageous beyond measure, and, if he has the courage to witness, then we must have the courage to listen.

He tells the story of colonisation and genocide and the determination of buried children to become the seeds of regeneration.

He also speaks of matriarchy, the dehumanizing process of colonisation where a balanced culture was destabilised on the European model of post-Christian misogyny, and the importance of recognising women’s voices in the womb-shaped ceremonial houses.

We are a choir, he tells us and his pitch is perfect as he asks of his wounded but undefeated Indigenous brethren:

We must prepare ourselves as Indigenous Peoples to be involved and engaged in the heavy work of healing and reconciliation. For many of us, we will be struggling to overcome that harm, but we must for the sake of our children and generations to come.

And for non-Indigenous who must live through shame and blame to the truth that lies before us, we too must struggle to become the One he so generously envisions.

That he so movingly harmonizes the plainsong of his stolen childhood with the operatic rhetoric of the Big House, school for civilisation, is a gift to all who need to understand the meaning of social change as we begin the process that is essential to the peaceful evolution of a community of friends out of genocide.

Gilak’asla for the opportunity to heal.

*

Canadian People’s Poet Linda Rogers was welcomed to his Kwakwaka’wakw family by Chief Tony Hunt, who introduced the world to Northwest Coast art. She hopes to honour that privilege in her writing and advocacy for children and Indigenous artists. Editor’s note: Linda Rogers has recently reviewed books by Jody Wilson-Raybould, Carol Shields & Nora Foster Stovel, Mandi Em, Sue Goyette, Cid V. Brunet, and Betsy Warland.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “1598 All together now”

Linda, thanks for this compelling and heartful review. I will be ordering the book immediately. I’ve had the privilege of meeting Chief Joseph (at Continuing Legal Ed’s 1st Conference on Indigenous Legal Orders in 2012) and he is a uniquely inspiring person, one who has surmounted so much grief and hardship, he is able to bring a true openheartedness to his encounters. We are most fortunate to have a person of his integrity and stature amongst us! Sally Campbell

Thanks to the review for the opportunity to speak on the issues that matter to us, for the civil discourse that is our map to a better future.