1545 Cree identity in exile

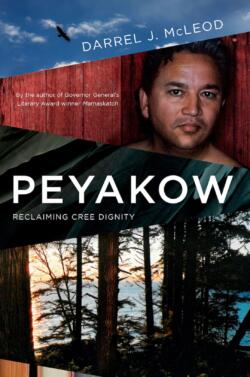

Peyakow: Reclaiming Cree Dignity

by Darrel J. McLeod

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2021

$29.95 / 9781771622318

Reviewed by Heather Simeney MacLeod

*

Darrel McLeod attended the University of British Columbia where he obtained two degrees – a Bachelor of Arts in French Literature and another in Education. Prior to becoming a writer, McLeod worked for the federal government as a chief negotiator of land claims, and as an executive director of education and international affairs with the Assembly of First Nations. Peyakow: Reclaiming Cree Dignity is McLeod’s follow-up to his debut book, which received the Governor General’s Literary Award for Nonfiction in 2018, Mamaskatch: A Cree Coming of Age, which I also reviewed in these pages. McLeod continues his story and memoir from Mamaskatch into Peyakow. Certainly, as indicated in its subtitle, Mamaskatch is a coming-of-age, a bildungsroman, and Peyajow continues the trajectory into the hero’s journey. That McLeod’s hero is the author himself is of no matter, for he embarks upon adventures, overcomes ordeals, defeats enemies, and is transformed. Indeed, peyakow is a Cree word meaning an individual is alone or travels alone, or, as McLeod’s book jacket states, “one that walks alone.”

Darrel McLeod attended the University of British Columbia where he obtained two degrees – a Bachelor of Arts in French Literature and another in Education. Prior to becoming a writer, McLeod worked for the federal government as a chief negotiator of land claims, and as an executive director of education and international affairs with the Assembly of First Nations. Peyakow: Reclaiming Cree Dignity is McLeod’s follow-up to his debut book, which received the Governor General’s Literary Award for Nonfiction in 2018, Mamaskatch: A Cree Coming of Age, which I also reviewed in these pages. McLeod continues his story and memoir from Mamaskatch into Peyakow. Certainly, as indicated in its subtitle, Mamaskatch is a coming-of-age, a bildungsroman, and Peyajow continues the trajectory into the hero’s journey. That McLeod’s hero is the author himself is of no matter, for he embarks upon adventures, overcomes ordeals, defeats enemies, and is transformed. Indeed, peyakow is a Cree word meaning an individual is alone or travels alone, or, as McLeod’s book jacket states, “one that walks alone.”

McLeod’s journey begins in poverty in Treaty 8 territory in northern Alberta. As with his coming-of-age tale, McLeod is a survivor of intergenerational trauma, cultural genocide, racism, and the Canadian Indian Residential School system, and he lives through addictions that have been inflicted upon his family, community, and the Indigenous peoples in general. His hero’s journey opens with him stating, “I’ve been living in exile from my homeland for over five decades, separated from my people, my culture and language, the rivers and streams, hunting grounds and berry patches — the entire ecosystem of which I am a part; an ecosystem that has been permanently altered” (McLeod quoted in opening matter).

As with most Indigenous heroes’ journeys, the adventure is often not permanently away from home because the hero returns, altered, towards home in the hope of reclaiming culture, community, and language.

Even the most cursory understanding of the Indigenous peoples in Canada (and elsewhere around the globe) will reveal the ordeals endured along the hero’s path: cultural genocide, racism in all its various structures, residential school, addiction, and trauma. In Peyakow, McLeod decides to leave the comfort of his home and the community he had built in North Vancouver with his partner to relocate to an isolated and impoverished area of northern BC — to an unknown landscape filled with many unknown aspects, including Nation. There he finds the familiar: “Through the bank of windows I could see large crows flitting between tall spruce trees and alders, cawing over each other impatiently and making guttural clicking noises. I thought of home […] the crows outside were identical” (p. 17).

McLeod suffers what my Cree grandfather would have referred to as the great unrest. He moves from the small Yekooche community (85 kms northwest of Fort St. James) to the village of Salmon Arm. Along with the move from the Cariboo region to the north Okanagan, McLeod changes positions from a school principal to “travel[ing] all over BC to work with many First Nations, urban and rural, developing college-level education programs and curricula” (p. 39). His unrest and ambition continue in his new work. For example, he works as part of an Indigenous delegation to the United Nations in Geneva and as an executive in the federal government. These adventures are evocative especially because each call is so fully and richly its own journey. McLeod is right to divide — for lack of a better term — his vignettes into chapters. Still, each chapter contains fully articulated characters on McLeod’s changing terrain as well as, I suggest, the spiritual elements that guide McLeod throughout his journey, such as the timber wolf that followed him from BC into Alberta.

Part of the hero’s journey is the defeat of enemies; however, for the Indigenous peoples of Canada — certainly in my experience and as documented in McLeod’s memoir — the enemies are not always as easily identifiable as, in my own experience, I ever hoped or expected. McLeod traces many of these opaque racist moments in his memoir. While working in Salmon Arm, McLeod recalls a colleague’s rebuke: “Darrel, I have to say, just by looking at you I can tell you that you are not Cree. With a name like McLeod, you are Metis at best” (p. 42). I must say, as a member of the Metis Nation and as someone who passes as white, that McLeod’s colleague’s comment upon his lineage and culture is devastating and, certainly and sadly, not a lone example. His ability to defeat those that wish to pull or push him down — either through the exposure of his family or his own secrets – understandably shifts between fear and acceptance. It is his decision to rely upon his ancestors and the natural world that supports him through his travails.

McLeod likens his position in the world to sandpaper between cultures — a metaphor McLeod locates in Chrystos’s poem, “I Am Not Your Princess.” However, McLeod’s position as bearing witness is far more apparent in both his memoirs than that of sandpaper. He reveals his own life in his unflinching addressing of youth suicide in Indigenous communities, his exposure of the long-term impacts of residential schools within one community (revealing poverty in all its shame), his unveiling of the challenges of Indigenous peoples to attain education, his own obstacles to forward motion within the workplace while subjected to racial discrimination, and his own witnessing and exposure of government corruption. He reveals how he learned to live his life imperfectly but with respect for himself, his family and ancestors, his past and inherited memory. Always the nonhuman animal is evocatively present, and always McLeod bears witness with joy and displays an easy way towards laughter and optimism. I would suggest that despite the title of his memoir, McLeod doesn’t walk alone. He treads paths that are crowded with ancestors, crows, and a timber wolf.

Still, McLeod is transformed through a merging between the Indigenous peoples of what is, at this historical moment, identified as Canada and its problematic ecosystem: “a land now traversed by pipelines and penetrated by compressor stations and pumpjacks” (opening matter). The connection between the ecosystem and the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island is apparent when McLeod writes, “After laborious research and deep reflection over the last few years, I now grasp how my extended family, once proud and strong, independent and thriving, became disenfranchised and impoverished while the society around us grew increasingly affluent” (opening matter). McLeod points out that he has “come to understand about the colonization of [his] people and tell the story of how [he] struggled to turn around [the Indigenous peoples] dystopian lives, striving to salvage some degree of happiness” for all involved (p. 1). His memoir illustrates how this work was undertaken and worked towards. As I noted when reviewing Mamaskatch, this is the work of truth and reconciliation, and most importantly, as McLeod so deftly illustrates, it is a long and arduous process. Peyakow: Reclaiming Cree Dignity is an Indigenous hero’s journey tackled with unwavering honesty and insight by a remarkable writer and man.

*

Heather Simeney MacLeod is a member of the Michif Nation. She has published four collections of poetry; the most recent, The Little Yellow House, published by McGill University Press. Her poem, “All Evidence to the Contrary” was shortlisted in the Magpie Poetry Prize in 2022, and her poem “Arctic Archipelago” won second place in Room’s poetry contest in 2021. Heather works as an Assistant Teaching Professor in the Department of Media and Visual Arts at Thompson Rivers University. Editor’s note: Heather MacLeod has also reviewed books by Darrel McLeod (Mamaskatch), Ivan Coyote, Garry Gottfriedson, and Robert Eighteen-Bisang & Elizabeth Miller for The British Columbia Review.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster