1400 There is always laughter

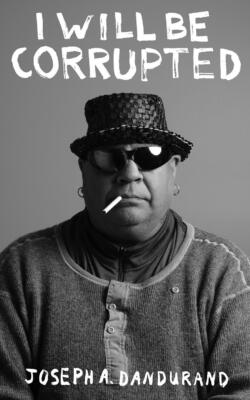

I Will Be Corrupted

by Joseph A. Dandurand

Montréal: Guernica Editions, 2020

$20.00 / 9781771835060

*

The East Side of It All

by Joseph Dandurand

Gibsons: Nightwood Editions, 2020

$18.95 / 9780889713802

Both books reviewed by Paul Falardeau

*

Joseph Dandurand has been busy lately. Since the Covid pandemic began, he has written three books of poetry, three plays and two manuscripts of short stories, with more on the way. A member of the Kwantlen First Nation, he lives and writes from his home on an Island in the Fraser River, about 20 minutes east of Vancouver. These two locales, Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and his peaceful home on the river, are the rotating nuclei of his poetry in the two collections he released late in 2020, I Will Be Corrupted and The East Side of it All, which was shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize in 2021. Though the two books could be seen as companion pieces, and both share many of the same themes and tropes, their focus shifts between different aspects of the poet’s life. East Side focuses on Dandurand’s journey from dispossessed drug-user, living in one of the Downtown Eastside’s (DTES) infamous SROs, to his acceptance of his gifts of a storyteller and healer. I Will Be Corrupted focuses on what comes after, the day to day experiences of normality, and the depression beneath the surface of the everyday.

Joseph Dandurand has been busy lately. Since the Covid pandemic began, he has written three books of poetry, three plays and two manuscripts of short stories, with more on the way. A member of the Kwantlen First Nation, he lives and writes from his home on an Island in the Fraser River, about 20 minutes east of Vancouver. These two locales, Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and his peaceful home on the river, are the rotating nuclei of his poetry in the two collections he released late in 2020, I Will Be Corrupted and The East Side of it All, which was shortlisted for the Griffin Poetry Prize in 2021. Though the two books could be seen as companion pieces, and both share many of the same themes and tropes, their focus shifts between different aspects of the poet’s life. East Side focuses on Dandurand’s journey from dispossessed drug-user, living in one of the Downtown Eastside’s (DTES) infamous SROs, to his acceptance of his gifts of a storyteller and healer. I Will Be Corrupted focuses on what comes after, the day to day experiences of normality, and the depression beneath the surface of the everyday.

Both collections highlight the kind of terse, yet lyrical, style that has garnered so much acclaim for Dandurand. He makes good use of plain, relatable diction that he nonetheless elevates. Considering that his subject matter is often serious and tragic — life on the streets, drug use and addiction, missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, residential schools, suicide, and depression — Dandurand makes good use of everyday language to centre these realities without losing them in his language. Likewise, when he brings the reader to the peace and quiet of his riverside homeland, this clean, clear language allows these images to shine without too much added floweriness. In any case, the work comes across as conversational. While reading his poetry, one feels as if the man himself is sitting there across the table, lit smoke dangling at his lips, speaking the poems to you. Dandurand himself has admitted the language of his poems is meant to elicit the spoken word. In an interview with open-book.ca, he says:

I am always struggling with publishers with my use in my poems of the word “AND,” but for me I write like I would read the piece out loud and the word “AND” gives me time to breathe as I chop through the poem. When I come to endings of my poems there are usually one word stanzas and I slow down as I breathe the last words out.

This kind of spare, conversational, and refreshingly real language is not only a stylistic touch, but a vessel that showcases the dualities that are present in much of his work. With bluntness, he reveals vulnerability; moments of toughness are often a shield for places of softness, and it is rare that he lets us sit in the brutal realities of the life he portrays without adding moments where he finds beauty in the world around him. These contradictions are often embodied by the recurring character of the Sasquatch, who walks between the tree-clad mountains and the grimy streets of the DTES, and seems to be somewhat of an alter-ego for Dandurand himself. Often thought to be a fearsome creature, large, hairy and strong, the Sasquatch is frequently shown in these poems as a loving, empathetic character, someone who is misunderstood. In “Desire that Carved Me” from I Will Be Corrupted, he writes that,

once I sat down and had

tea with a sasquatch

and he said he had seen

all the mountains on earth

and I believed him as

he sipped his tea and stared

off across the valley to the

snow-capped mountains above.

Though both books grapple with the litany of trauma that Dandurand and the people in his life have endured, The East Side of It All really starts with a focus on the reality of life in the DTES. Here we find the poet giving a voice to the most marginalised peoples. In “Violins,” he paints a picture of homeless folks pushing stolen grocery carts, picking through trash for treasures of discarded skag in used syringes. His empathetic pen and keen ear relate that, “the squeaking wheels/ begin to sound like violins/ of a pathetic symphony/ and the notes are unplugged/ in unison as the wheels/ turn and stop and repeat.” In “Street Scene” he chronicles the day-to-day of drug use, from the working girls, “Fifteen minutes later/ she is back and lights her/ glass pipe, inhales her lifeline, exhales/ the sorrow, then tries again to stand straight.” To forgotten elders, “The addict says he is fine/ but they carry him off anyway/ and he spends his day high as a kite/ imagining he is back/ home on his reservation/ and everyone around him/ is his family. He talks to a nurse/ as if she were his mother.”

Despite the heartbreaking realities faced in the early part of the book, The East Side of It All is also ultimately a book about healing. It’s clear that Dandurand’s scenes of human suffering are made possible by colonialism by the Canadian state. We hear stories of residential schools and the molestation, humiliation, and abuse that happened there, and their echoes in the actions of the residents of the DTES’s streets. We also have the ever present “pig-farmers” and “predators” that lurk through alleyways and hang out of car windows at night, taking women who are never seen or heard from again. But Dandurand is not helpless, he fights. He also realises that he has a gift of storytelling and healing and begins to use it. “The sasquatch/ rubs his hands together and places them/ upon the wounds,” he writes. “The man is healed/ and says Thank you as the sasquatch/ turns and pukes out the poison/ he has taken from his brother.” Storytelling is a form of justice, and of healing that often comes not in anger, but in community and laughter, like in the ending of one of the best poems of the collection, “There is Always Laughter”:

Our people struggle but there is always laughter.

This is a gift that will never be taken away nor

will they ever change us. We even laugh at funerals,

laughter covering the pain for yet another lost soul

gone too young and too tragically. The laughter is

ours as we weep and ask why, again, as we bury

our love and all of us go home as a sasquatch

and a wolf and a bear and a child who was put

on a train appear and sit around the fresh dirt.

They do not cry, no, they laugh at it all.

*

Where East Side focuses on the experiences of the street, and the transition to a place of healing, I Will Be Corrupted finds Dandurand in a different place. Though we often revisit some of the same tragedies, we also now find him in his peaceful home on an island in the middle of the Fraser River. Here, the characters of sturgeon, Hawk, Eagle, and Coyote replace the downtrodden denizens of the city. This new physical location reflects Dandurand’s new stage of healing. Yet, the nuance here allows us to understand that a change of scenery and a fresh perspective cannot erase the past. The poems of I Will Be Corrupted all fade to single word lines. This seems to replicate the day in, day out, of living a new life of healing; of continuing on. Often this seems to evoke both the beauty and the banality of the sublime, the repetition of healing and a life without numbing. Though outwardly things seem more serene, beneath the surface there are still painful memories, thoughts of suicide and depression. For example, “I imagined hanging myself/ in the smokehouse at the/ back of my house but I could/ never tie a proper knot/ and I just stood there with/ the rope around my neck/ as the smell of smoked fish/ covered me.” Dandurand understands intimately that being saved comes with an immense sense of guilt and that healing is a lifelong practice. Ultimately there will be regression and doubt and regret. I Will Be Corrupted is one of the best and most honest reflections on the strength required for such a journey.

Where East Side focuses on the experiences of the street, and the transition to a place of healing, I Will Be Corrupted finds Dandurand in a different place. Though we often revisit some of the same tragedies, we also now find him in his peaceful home on an island in the middle of the Fraser River. Here, the characters of sturgeon, Hawk, Eagle, and Coyote replace the downtrodden denizens of the city. This new physical location reflects Dandurand’s new stage of healing. Yet, the nuance here allows us to understand that a change of scenery and a fresh perspective cannot erase the past. The poems of I Will Be Corrupted all fade to single word lines. This seems to replicate the day in, day out, of living a new life of healing; of continuing on. Often this seems to evoke both the beauty and the banality of the sublime, the repetition of healing and a life without numbing. Though outwardly things seem more serene, beneath the surface there are still painful memories, thoughts of suicide and depression. For example, “I imagined hanging myself/ in the smokehouse at the/ back of my house but I could/ never tie a proper knot/ and I just stood there with/ the rope around my neck/ as the smell of smoked fish/ covered me.” Dandurand understands intimately that being saved comes with an immense sense of guilt and that healing is a lifelong practice. Ultimately there will be regression and doubt and regret. I Will Be Corrupted is one of the best and most honest reflections on the strength required for such a journey.

Ultimately, the river itself is one of the key elements in these poems and Dandurand’s redemption. He gets back in touch with himself and his ancestors by heading out on the water and casting nets to catch fish for his children. There are many poems where he imagines himself or others slowly sinking to the bottom of the water to feed the fish in turn:

over time you come to

accept it all and you fall

asleep and dream about

your boat sinking to the

bottom of the river and then

you wake up and go to the

river and get in your boat

and you throw your net

and watch it drift and then

all of a sudden your net begins

to dance and you race over and

pick a twenty-five pound spring salmon

and throw it in your boat and begin

the day with a smile and a dream

of a sinking boat.

Through the course of I Will Be Corrupted it seems that Dandurand learns to heal his wounds by not fighting against them or struggling to hold his past behind him. He says that his poetry has opened doors for him, but it has been painful to let what he has kept inside walk out that same door to be seen by the world. “To me that is the greatest gift I can give to the world. To simply teach others that it is okay to go inside of yourself even if it scares you, even if it is so much a part of you that sharing it is one more step to that knocking at the door.” These poems seem to understand the duality of this and the duality of life itself. The river may feed you, but you may also become its food; one may be at peace, but also in struggle under the surface; that we may not find answers, but may be content anyway.

These are some of the moments of beauty in Dandurand’s two books from 2020 that can be found in the everyday and the mundane, moments that in turn give birth to sublime thought. There are no answers here, but as the river flows by him, as it has done since time immemorial, Dandurand ultimately finds for himself and his readers the greater rewards of a connection to the large and smallness of the sacred and infinite cycles of life.

*

Paul Falardeau is a poet, essayist, brewer and most recently, an English teacher, living in Vancouver, a city on the unceded lands of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations, whom he offers respect and gratitude. He is a graduate of University of the Fraser Valley and Simon Fraser University. He has published in Pacific Rim Review of Books, subTerrain, and Cascadia Review, and he contributed an essay to Making Waves: Reading B.C. and Pacific Northwest Literature (Anvil Press, 2010). Editor’s note: Paul Falardeau has recently reviewed books by Richard Wagamese, Lydia Kwa, Sam Weibe, Yasuko Thanh, Richard Van Camp, Michelle Sylliboy, and Trevor Carolan.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and writers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster