1370 Documenting monopoly

“Opposition on the Coast”: The Hudson’s Bay Company, American Coasters, the Russian-American Company, and Native Traders on the Northwest Coast, 1825-1846

Edited and introduced by James R. Gibson

Toronto: The Champlain Society, 2019

$99.00 / 9780772764416

Reviewed by Peter Grant

*

A game of monopoly: The Bay, of department store fame, was once the terror of the fur trade

A game of monopoly: The Bay, of department store fame, was once the terror of the fur trade

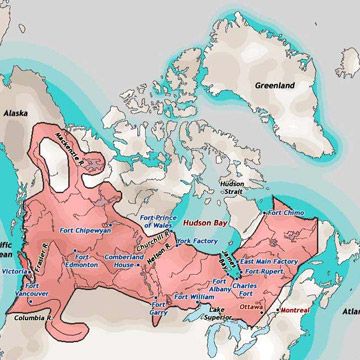

This interesting selection of documents comes from the period when the present U.S. states of Oregon and Washington and all of British Columbia south of 54º40’ N latitude and west of the Rockies, a vast and varied domain called Columbia by the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and Oregon in the United States, were under joint occupation — a bilateral free-trade agreement, in other words. Between 1818 and 1846, the HBC and American fur traders duked it out for control of the peltry, while American and English diplomats laid claim to large swaths of the other’s claimed land. Indigenous trappers and carriers played the traders against one another, driving up the price of pelts. The HBC, too, relentlessly bid up furs to levels that were ruinous to the freelance American traders, but not to the HBC — the company had deep English pockets and a military-style command-and-control modus operandi, executed on the ground mostly by tough-as-nails Scots and Canadians. The HBC was the British government by default over all those lands and much more besides, because geography was a huge hindrance to communication with the motherland, necessitating long trips around capes Horn (outbound) and Good Hope (on the return voyage) or else following the gruelling overland routes between Hudson Bay and the Pacific Coast.

The corporate squeeze caused the American presence on the Northwest Coast to dwindle. One notable defector to the HBC was William Henry McNeill, an American veteran of the fur trade, a skilled shipman, the husband of an Indigenous woman of a prominent Kaigani Haida family. The last straw was the British company’s supplanting the Americans as suppliers of provisions, trade goods and furs to Russian America, a colony that took in much of Alaska, Yukon and BC north of 54º40’. So it went in the interior of Columbia/Oregon: independent American fur-traders could not make a profit and retired from the field. By 1839, the HBC had established monopoly control over Columbia/Oregon. They skunked the Americans. The competition was far from peaceful — more like a prolongation of the War of 1812-14 by other means.

“Opposition on the Coast” is the work of James R. Gibson, a historical geographer who has published several deeply researched books about North West America: Imperial Russia In Frontier America: The Changing Geography of Supply of Russian America, 1784–1867 (Oxford 1976); Farming the Frontier: The Agricultural Opening of the Oregon Country 1786-1846 (UBC Press 1985); Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods: The Maritime Fur Trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785-1841 (McGill-Queen’s 1992); The Lifeline of the Oregon County: The Fraser-Columbia Brigade System, 1811-47 (UBC, 1997). Gibson has published notable scholarly articles on the subject as well. The present work adds to an already impressive body of text about Oregon/Columbia. Altogether, Gibson’s oeuvre earns a place in the pantheon of Joint Occupation scholarship with Frederick Merk, Harold Innis, W. Kaye Lamb, E. E. Rich, John S. Galbraith, Peter C. Newman, Richard Mackie, Mary Molloy, Stephen Bown and other heavy hitters. (The reviewer, while familiar with regional history and geography, is a recent recruit to this subject.) The present volume is among the recent contributions of The Champlain Society, the ancient Canadian publisher of books, uniformly clothed in scarlet, of foundational Canadiana — “the adventures, explorations, discoveries, and opinions that have shaped Canada … the eyewitness accounts” (so reads the Mission Statement). It has published eighty-two volumes so far, each blazoned with the society’s circular seal depicting a stylized galleon with the motto In mari viae tuae (from Medieval Latin liturgy meaning, roughly, “Your pathways are on the sea”).

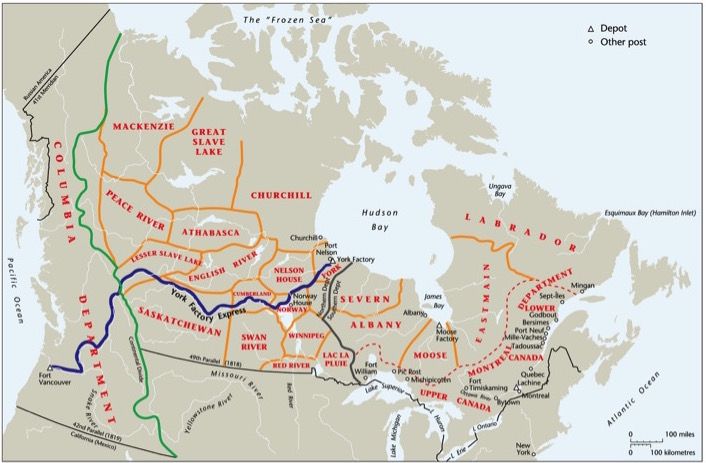

The twenty-seven documents in “Opposition on the Coast” are introduced by an 80+ page overview. The narratives follow only the coastal fur trade, within a tightly-focussed period that began with the HBC’s establishment of Fort Vancouver in 1825, near the mouth of the Columbia River, and ended with the Oregon Treaty of 1846, which established the 49th Parallel as mainland British Columbia’s southern boundary with the U.S.A. (This happened, of course, BC: before colonization.) It is hugely the story of the HBC’s pursuit of monopoly control of the fur trade on the Pacific Coast and interior drainages. The starting point is governor George Simpson’s Grand Design (so styled by the editor) after the North West Company’s routes, forts and personnel fell into his lap, backed by a national claim to ownership of Columbia/Oregon and Rupert’s Land. The HBC built forts on the coast near the mouths of rivers that were Indigenous trade routes. It imported the singularly versatile steamboat Beaver. It over-trapped the spacious Snake River drainage, making it a fur desert to Americans. Simpson, meanwhile, performed adroit end runs, subverting the American interest in trade with the Russians. Two obstacles frustrated the Grand Design. One was Simpson’s scheme to market furs in China, interdicted by the East India Company’s monopoly on British trade there. (The HBC stuck with Plan A — shipping them back to England.) Another dud was the establishment of Fort Langley on the Fraser River in 1827 as a potential new headquarters north of the 49th Parallel and the coastal terminus of a route from the interior that was alternative to the Columbia, with its ship-devouring mouth of shifting sandbars. Simpson abandoned the Fraser scheme when he experienced first-hand the challenge of even surviving passage through the Fraser Canyon.

Together, the introduction and documents show “how the company entered this important new enterprise of what it called the ‘coasting trade,’ and how it fared.” The material is presented chronologically “so as to underline the changing character of the coast trade and the evolution of the HBC’s involvement.” A brief prefatory note glosses the criteria for inclusion: “the most pertinent, informative, and trustworthy of the dozens of reports, letters, journals, and memoirs that deal wholly or partly with the coast trade of the American, British, Russian, and native contestants.” Both American players and Indigenous peoples are everywhere in the narrative, in both documents and introduction, but the title of the book requires a little qualification to be accurate. American interests got pretty much dealt out of the selection process, and there are no Indigenous documents, as explained in the prefatory note: “The voices of the natives are largely silent, the few recorded oral narratives (what the Tsimshians call adawx) being too general to be of much service.”

More than half the documents in “Opposition” were generated by the HBC, and two are texts of agreements between the HBC and the Russian-American Company (RAC); they account for four-fifths of the allocated space. As to the composition of the fifteen HBC documents, all but one were internal communications; the other was James Douglas’s private diary of an 1840 trip from Fort Vancouver up the coast and back on a tour of inspection and reconnaissance, a diary that narrates many eye-opening scenes, like the dressing down Douglas received from Captain McNeill over who gave the orders aboard the SS Beaver. The RAC was the source of ten of the entries, to which 27 pages are devoted, not including the forementioned agreements. The American interest is represented by a single text, an agreement between a Boston fur trading company and the RAC — two pages. Eight documents have previously been published and are mostly identified as such in footnotes. The source footnotes indicate that the documents were taken from original archival material or copies of same, as the prefatory note explains: “All of the 27 documents have been selected from the archives of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in the Archives of Manitoba, Winnipeg; the BC Archives, Victoria; and the extant records on microfilm of the Russian-American Company (RAC) in the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.”

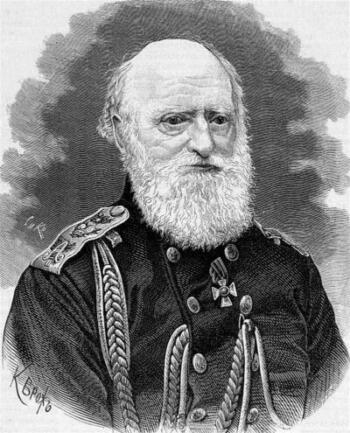

The stars of the show appear to be the translated Russian material, including nine internal communications that provide perspectives on the issues of occupation and trade with the HBC and the Americans. Reading the RAC papers in tandem with contemporary letters and reports of the HBC, one may compare the same events from the different points of view, interrogate them for veracity, and savour the candour of internal communiqués. If those documents have not before seen the light of day in English, their publication opens a window on the curious diplomatic dance between the field marshals of two monopolists, Simpson, the bastard from Rossshire, for the HBC, Baron Ferdinand von Wrangell for the RAC. They met first in St Petersburg and, in 1839, in Hamburg to finalize their Northwest Coast trade agreement. The fourteen documents in this vein cohere, and the narrative is relatively intelligible to a newcomer.

The HBC’s communications are more problematic. The letters and reports typically dwell on several topics, if not multitudes, covering months-long operations, so that one is hard-pressed to decide which details carry the freight, the through-story that the editor promised would demonstrate how the HBC “entered the ‘coasting trade,’ and how it fared.” To introduce the subject, the editor chose an analytic approach, considering, in turn, “intelligence, ships, captains, posts and goods.” (“Intelligence” concerns the HBC’s inquiries into the operation of the coastal fur trade to which they were newcomers, and “goods” includes articles both for trade and to provision the posts.) A long, highly detailed section analyses the competitors in the trade and their evolving interactions.

One consequence of the analytic approach (as against, say, building a unified narrative) is to sow frustration. Instead of one narrative, the introduction offers many. The search for coherence is complicated by convoluted text. One encounters paragraph-long sentences whose flow is interrupted, often, by parenthetical asides. Footnotes pepper the text, and much of the footnoted material is substantive, requiring the reader to evaluate one by one their significance vis-à-vis the text.

Readability and fragmentation are not the only hindrances to understanding the introduction. It makes reference to specific documents parenthetically, e.g., “(Document 16)” or in footnotes. The editor is a deep researcher with a wealth of documentary material at his fingertips. The 325 footnotes in the introduction attest to that, and the documents section has more than 200. The many sources drawn on in the introduction seldom come from the documents in view, however, and the introduction typically quotes a few words or phrases from them, if that. Reference is made to Document 26, for example, in the introduction, in the context of the Chilkat Tlingits “travelling 75 miles up the Taku River to trade with interior natives (Document 26).” The document cited is Chief Factor James Douglas’s Diary of a Trip to the Northwest Coast (mentioned above), which runs 37 pages. Where is the passage to which the introductory reference alludes? Repeated close readings of the 37 pages did not uncover any reference to the “Chilkat Tlingits” or the 75-mile trip up the Taku. One is left with the impression that the parenthetical reference to “Document 26” is not intended to steer the reader to any specific evidence, much less to interpret, summarize or otherwise elucidate the document. Broadly, one searches in vain for the thinking behind the choice of any particular document, or a summary of their significance, each or severally. Nor does any document have an introduction to frame it. Which creates a challenging task for the reader who wishes to puzzle out the linkages: one must develop a conversant knowledge of both the introduction and documents. To the dogged and persevering, the lack of guidance is a motivator.

A couple more examples will illustrate this reader’s difficulty interpreting the documents. Consider John Work’s October 1838 report on the HBC’s coasting trade from Fort Simpson. The document is referenced three times in the introduction. The first (p. 56) quotes a sentence from the report about the logic of Indigenous traders’ migrations to the highest-paying markets. A 13-line quote (p. 58) recounts the dreadful smallpox epidemic in 1836. A one-line quotation (p. 75) asserts the limited opportunity to expand the trade, given the Russians’ exclusion of European traders from their Alaskan domain. The references are mere citations, airy and vague to boot, among many, to texts that require much more of the reader than bemusement. An array of numerical tables occupies nearly half of the Work report’s 18 pages, but there’s no interpretation. The introduction functions on a parallel track to which the documents function as mere source material. The logic of this is backwards. The documents are in fact the main event and the introduction subservient to the reader’s need to understand them, or should be.

Seven pieces were not accorded any reference at all in the overview. The most curious is Document 17, Chief Trader Peter Ogden’s Report on Transactions at Stikine, 1834. Peter Skene Ogden, tough-as-nails Quebecker with a law degree, sailed the HBC brig Dryad into RAC waters near the mouth of the Stikine River with the intention of building a fort. So much was allowed by the HBC-RAC convention of 1825, Ogden argued. An officer representing the RAC forbad them nonetheless, and there was a tense standoff while Ogden waited for governor von Wrangell to consider the HBC claim. That seemingly inconsequential, failed adventure was indeed consequential and is well-known to History as The Dryad Affair. The matter is glossed in the introduction, as is the two parties’ progress to the HBC-RAC agreement of 1839. But there’s no reference to Document 17, Ogden’s report. And there’s no linkage with the fascinating Document 18, von Wrangell’s account of the affair, which differs in material ways from Ogden’s. The reader should not be left to pull those threads together. On a trivial plane, the source footnote for Ogden’s report makes no mention of its appearance in McLoughlin’s Fort Vancouver Letters, First Series, published by The Champlain Society in 1941. The same must be said of Document 18, which appeared (in a markedly different translation) in an appendix volume to the Proceedings of the Alaskan Boundary Tribunal (1904).

Grasping the twists and turns of this dramatic chapter of our regional history requires a knowledge of the larger historical arc, one would think. A sketch of the genesis of the international competition for furs is, however, not to be found here. Missing is any mention of the American fur traders’ dominance on the Northwest Coast for a generation after they first appeared (ship Columbia Rediviva, Captain Robert Gray, in 1788). Missing is the fact that, in 1792, rival captains Gray and George Vancouver, RN (United Kingdom) were in the vicinity of the Columbia River’s mouth within two weeks of each other. Both proclaimed possession of all the lands drained by the mighty Columbia. (By volume of discharge it is the fourth largest river in North America, in a watershed of some 668,000 sq km.) Lieut. William Broughton, RN explored the lower Columbia in October 1792, leading the Brits to challenge American precedence. That’s not in there either. Missing, too, is a résumé of the events leading up to the 1818 free-trade agreement. After the inconclusive War of 1812-14, both countries advanced claims to the interior regions drained by the Columbia. This led to the joint occupancy agreement, which was renewed twice, while rival diplomats preened and politicians postured to gain ascendance.

Another piece of missing background concerns the HBC’s absorption of its bitter rival the North West Company (NWC) in 1821. The HBC, 150 years old, synergised with the NWC. The NWC, a Canadian company, based in Montreal and Fort William, employed such outstanding explorer-developers as Alexander Mackenzie, Simon Fraser and David Thompson. Peter Skene Ogden and John McLoughlin, another Canadian (licensed to practice medicine), were Nor’Westers long before before they became chief factors in the HBC. By the merger, the HBC gained a foothold on the Pacific to complement its monopoly in Rupert’s Land. That was the Columbia Department. (Funny thing — our province has the old North West Company moniker in its name. It was originally Columbia District, which took in the drainage basin of the Columbia River; while the separate New Caledonia District encompassed the Fraser River watershed and was so named by Simon Fraser himself. The districts were combined by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1826.) Coincident with HBC-NWC merger was the appointment of George Simpson as governor of the Northern Department– an astounding coincidence, given Simpson’s genius (some would say evil genius) in appropriating the NWC’s model of far-flung overland networks and hooking them up to the HBC’s coastal operations centre at Fort Vancouver. Any account of the period should grapple with the significance of that coincidence in the rise of the HBC as a prodigy of transcontinental business with unique powers, run by, for all intents and purposes, the man who wrung jaw-dropping services from his servants and gentlemen and made the fur trade profitable again. (Simpson’s authoritarian powers have been compared to Napoleon’s; Simpson’s empire was the larger in area if not in GDP; both wielded tyrannic power over their subjects.)

In the contest of the rivalry with the Americans, the HBC won every battle — but lost the war. Its control of trade in Columbia/Oregon was rendered moot by the thrilling saga of the Oregon Trail, when a few thousand settlers, aroused by the prospect of rival U.K. owning a huge chunk of North America, made the arduous overland journey from the United States; a colony got settled in the Willamette Valley (the river of that name flows through Portland, Oregon near its confluence with the Columbia); the settlers appealed to the United Sates to proclaim “Oregon” US territory, putting it on the high road to statehood. Settlement trumped the vagaries of trade. Little of that is to be found here, however. Gibson sums up the experience of Joint Occupation as “a hollow, if not a pyrrhic, victory” for the HBC, for several reasons — depleted populations of sea otter, fur seal and beaver; the collapse of the European market for beaver pelts as the beaver hat went out of fashion; the high cost of outbidding American coasters during the 1830s; the consequential depreciation of returns and dividends; and a shrinking labour pool. His conclusion is that “all in all, it was time for the HBC and the RAC [Russian-American Company] to follow the lead of the ‘Boston men’ and seek profitable alternatives to the waning fur trade.”

But wait, is that all the company achieved in those 28 years? It can be argued that the HBC pulled off a huge save for the British Crown when it established Fort Victoria in 1843: besides giving the HBC an option for relocating its Pacific headquarters, it gave the British a fallback position on its land claims, to make the 49th Parallel the boundary of British and American territory, which effectively squelched the American clamour for all of Oregon/Columbia (“54º40’ or fight!”). There followed the full British colonial treatment, when Vancouver Island was privatized (to the HBC), followed within nine years by the Crown-colonizing of mainland British Columbia; the two united in 1866, and just five years after that, the united colony became a Canadian province. Less than thirty years, in other words, from a trading post on Vancouver Island to provincehood. The little fort was suddenly the capital of a vast domain whose natural resources, thanks to Section 92 of the British North America Act, were to be managed by an elected premier according to the high tenets of responsible government, which in the real world tends to become democratic dictatorship, which somewhat resembles Simpson’s dictatorial operation of the HBC. The HBC laid the foundation for that colony and saved Britain’s bacon on the Pacific slope and coast. The HBC went from pinnacle to pinnacle, morphing as it went, and The Bay is of course still with us. Not inconsiderable achievements, if not entirely aboveboard. The narrow field of vision of “Opposition” misses such larger themes on the consequential side of the joint occupation’s historical arc.

It is a fascinating read nonetheless, if not an easy read, and it brings together many salient documents. It’s good to have this material ready to hand. Thanks to Gibson’s erudition and meticulous sourcing, the book will make a useful reference.

*

Peter Grant is the author of seven books about Vancouver Island (in print: Victoria: A History in Photographs; Wish You Were Here: Life on Vancouver Island in Historical Postcards; Vancouver Island Book of Everything; Vancouver Island Book of Musts; Vancouver Island Imagine, with Boomer Jerritt) and is the proprietor of the local history blogs Oak Bay Chronicles and Spanish Influenza in Victoria, Canada 1918-1920. His most recent publication is, “A 1918 Influenza Outbreak at Haskell Institute: An Early Narrative of the Great Pandemic” (Kansas History, 43:2 Summer 2020). He lives in Victoria. Editor’s note: Peter Grant has also reviewed books by Carol Blacklaws & Rick Blacklaws, Ian Gibbs, and Gwen Curry for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster