1331 Reverend Wright & the wrongdoers

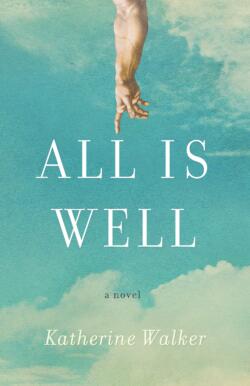

All Is Well

by Katherine Walker

Saskatoon: Thistledown Press, 2021

$24.95 / 9781771872157

Reviewed by Heather Graham

*

Christine Wright, the protagonist of Katherine Walker’s novel All Is Well, is a recently ordained priest in the Anglican Church of Canada with fifteen years of military service to her credit, some of it in Special Forces. She is also a recipient of the Victoria Cross, Canada’s highest military award. Quite a pedigree, not to mention quite an interesting career change for someone to undertake in midlife.

Christine Wright, the protagonist of Katherine Walker’s novel All Is Well, is a recently ordained priest in the Anglican Church of Canada with fifteen years of military service to her credit, some of it in Special Forces. She is also a recipient of the Victoria Cross, Canada’s highest military award. Quite a pedigree, not to mention quite an interesting career change for someone to undertake in midlife.

And what kind of a story can readers look forward to with such a protagonist in the narrative’s lead position? Something “weighty” seems the obvious answer: a spy thriller, perhaps, or at least a mystery of some kind, with Reverend Wright cast in the role of amateur sleuth. In fact, although the novel includes two, say we say, unnatural deaths, All Is Well is not a serious read, in the usual sense. Our protagonist is deeply troubled, and her attempt to attain a state of “soul recovery,” as she calls it, is certainly serious, but there is a lightness in the telling of this tale, a comic sensibility at work, that makes it anything but earnest or solemn.

The setting is Victoria, capital of British Columbia, and Christine’s church, together with the manse that is her home, is located not too far from the downtown area on a street that anyone familiar with the city will be able to pinpoint at once. Events take place during the time of Covid, but a Covid very different from the one that the world has been living through for the past almost two years. Masks are referred to only briefly, with little evidence that they’re actually being worn by anyone, and there’s definitely no social distancing or worry about the dangers of public gatherings. Church services are held, there is a wedding, AA meetings, visits to a pub, and even a boisterous Fun Run through city streets; the harsh realities of the pandemic have no part to play in this story.

The first death in All Is Well occurs just before the curtain goes up, and the story begins with Christine standing over the dead body of Terry, one of her parishioners, the weapon that dealt the lethal blow still clutched in her hand. What to do? It was self-defence, so the obvious answer is to call the police. Instead, Christine wraps the body in a rug and buries it in the churchyard. By herself. Impossible, you say? But this is someone with military training: “Christine can dig a trench in six minutes.” In the end it takes a little longer than six minutes, but at least it is done. Now she can move on to the really important matters in her life, like the upcoming Easter celebrations.

Does all this seem a bit silly, or at least implausible? It does indeed. By this point, the reader will have twigged to the fact that in the world of All Is Well, expectations of verisimilitude are irrelevant. This is a fanciful tale, where the constraints of real life don’t apply. Nevertheless, a matter of import lies at the heart of this story: a woman who is suffering because she feels herself alienated from God. There are subplots involving some of the other characters, including minor ones, all experiencing some kind of grief in their own lives: Tom, Christine’s church server, who has lost touch with his little girl; the delightful Mrs. Dee, one of Christine’s church ladies, whose husband suffers from dementia.

Two of the characters in All Is Well are very different from the others. Each has their own reasons for wanting to destroy Christine, and, if not actual forces of evil, these two are definitely agents of malevolence, driven by hatred and vindictiveness. One of them is unspeakably vile, and what goes on in his head is not easy to read. But they both have specific roles to play, and their outcomes are exactly what they should be. A little far-fetched, perhaps, but consistent with the imaginative nature of this particular fictional world.

Every once in a while during the course of the story Christine says to herself, by way of encouragement and comfort, “All will be well.” This personal mantra, expressing her basic belief, despite all of her uncertainties, in the ultimate goodness of God, evokes the words of Julian of Norwich, fourteenth-century English mystic, who most famously said, “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.” The presence of this idea in Walker’s story of spiritual healing is not incidental or without significance. Joey, Christine’s spiritual director, assigned by their bishop to get her through ordination, tells her this: “We are made from love to love and be loved.” By the end Christine will have achieved inner peace and the acceptance of those she cares about. There is even the promise of some worldly love, in the person of a character with a history that makes it possible for him to understand and help her.

A note to the proofreading department at Thistledown Press, publisher of All Is Well: You might want to reset your word usage error alarm. Doors have jambs, not jams. Crowds teem, they do not team—unless, of course, they are forming up to play some kind of competitive game, which was not the case in this instance. A church has an altar, not an alter, which inadvertently made it through a few times. And mon cherie? Oops. These are definitely not earthshaking missteps when it comes to language usage, but they’re not ones that any publisher concerned about editorial professionalism wants to see in the books they send out into the world.

And yet another note to Thistledown, this time on a very different subject: Keep your eye on Katherine Walker. What is she working on, now that All Is Well is off her plate? Would she like to talk to someone about her ideas? Walker’s first novel is not great literature, not does it have any aspirations in that direction, but there’s an engaging quality to the story that keeps the reader turning the page to follow this particular cast of characters, and a freshness to the way the story is told that is very satisfying. All Is Well is the first effort of someone who may still be trying to find her writerly feet, and definitely a talent to watch.

*

Heather Graham worked as an editor for nearly thirty years, and during that same time made more than one foray into the seductive but fraught business of bookselling. Now officially retired, she indulges her bookish inclinations by taking on the occasional editing project, as well as trying her hand at the storytelling process itself and doing some of her own writing. She lives on Malcolm Island in Queen Charlotte Strait. Editor’s note: Heather Graham has also reviewed books by Luke Inglis, Susan Olding, Bernice Friesen, Traci Skuce, Michael Christie, Anny Scoones, Alexander Laidlaw, Jennifer Butler, and Terry Milos for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “1331 Reverend Wright & the wrongdoers”

I wondered what happened to Katherine after she stopped being curate at my church. Now I know! I’m recalling her discussion of St Paul’s horse… so I would expect a good story.