1238 Decolonizing Northwest Coast art

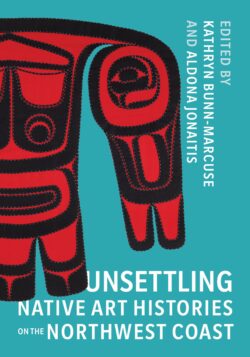

Unsettling Native Art Histories on the Northwest Coast

by Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse and Aldona Jonaitis (editors)

Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2020

$39.95 (U.S.) / 9780295747132

Reviewed by Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa

*

A few years ago, a First Nations man told me a story of two masks. The original, held in a museum, had been lent to the descendants and the community who originally owned it, to enable a well respected elder and carver to study it and create a new one, for the community to use in spiritual dances.

A few years ago, a First Nations man told me a story of two masks. The original, held in a museum, had been lent to the descendants and the community who originally owned it, to enable a well respected elder and carver to study it and create a new one, for the community to use in spiritual dances.

A ceremony took place in the big house, with an audience gathered to see the new mask danced in. The original mask and the new one lay side by side on a table behind a curtain, hidden from view. During the ceremony, the dancer left the floor for a quick change of regalia and to don the new mask. A helper placed the new mask in his hands, and he rushed back to the curtained entranceway, waiting for his timed entry. The carver stood next to him and helped him place the mask on his face. It didn’t fit! They hadn’t tried it on before. With a minute to go, the carver whisked out his knife and deftly carved away the inside of the mask more and more until it fit the dancer’s face, and just in time, the dancer entered the floor wearing the mask.

After the ceremony, they realized their mistake. In the dim light and the rush of the moment they had whittled out the wrong mask — the original one. They returned the newly altered original mask with trepidation to the museum, along with a letter of apology. Before long, they received a reply from the curator, delighted with the expanded history of the mask.

I learned a lot from this story, and it is still teaching me. Why was I shocked when I heard the museum mask had been whittled? Why was I taken aback upon hearing of the curators’ reaction? Who actually owns the mask? What does an object mean to a museum vs the original culture? Over time as my thinking expanded, I returned to this story again and again and like smoke and sparks from a big house fire, more questions arose: How does a European centric view of art differ from an Indigenous perspective; what is a museum; whose museum is it? This story came vividly to mind in reading Unsettling Native Art Histories on the Northwest Coast. This book, like the story of the masks, encourages us to pause and to rethink.

Prior to opening the book, I was unsure if it was a book on native “art” or about the history of “art” on the Northwest Coast, or about changing how we look at “art” or…? It is all that, yet so much more. The opening sentence in the introduction makes clear that no traditional Indigenous word for “art” exists on the Northwest Coast. To call a piece “art” is to remove it from Indigenous culture, kinship connections or spiritual power, to value it as a disembodied artifact rather than part of living tradition.

At first glance, the book is like a coffee table book: hardcover, relatively large (7” x 10”and 344 pages), and not too heavy to hold – yet it is impressive in its content and scope. I found it an enjoyable and fascinating read. Reasonably priced at just under $50 Canadian and produced on high quality paper with many beautiful photographs of Indigenous art, it deserves a place on the table to be seen, picked up, and browsed through again and again. And its varied content makes it a a valuable conversation starter. In a deeper sense, however, Unsettling Native Art Histories is so much more. The book has depth and layer upon layer of teachings that encourage the reader to take the time to savour the contents that might unsettle your – perhaps unconsciously — complacent mind and expand your understanding of the vibrant west coast artistic traditions.

The two editors both have wide experience as professors, authors, museum curators, and directors of Indigenous-focused centres: Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, curator of Northwest Native Art and Director of the Bill Holm Centre for the Study of Northwest Native Art, at the Burke Museum, University of Washington in Seattle; and Aldona Jonaitis, at the University of Alaska and the Museum of the North in Fairbanks. Their backgrounds set the underlying spirit of the book: one of respect, reconciliation, relevance, and reciprocity — the 4Rs. Advocated thirty years ago by two Indigenous educators, the 4Rs have become principles for building positive relationships with Indigenous people, something that many considerate museums are now trying to do. At a time when our very own Royal BC Museum is soul searching after an investigation found acts of systemic racism and discrimination against Indigenous team members, Unsettling Native Art Histories will help those involved in museums and readers grappling with what reconciliation might look like in institutions and even within ourselves.

While the editors represent museums in Alaska and Washington State on our northern and southern border, it is worth reminding ourselves that these borders are a settler construct of imaginary lines that separated families, put an end to work requiring border crossing, and disrupted traditional cultural events. These political borders have also put blinkers on our understandings; they can determine where we look and what we read. This book, with authors from both countries, ignores those borders and covers the whole Indigenous coast and our shared concerns.

Unsettling Native Art Histories has fourteen chapters and a conclusion by diverse authors — artists, weavers, carvers, academics, or museum curators. Half of the authors are Indigenous: Haida, Klahoose (Northern Coast Salish), Inupiag, Tlingit, Tahltan, and Kwakwaka’wakw. The chapters are organized into themed sections on “Cultural Heritage Protection — questions of rights and authorities,” “Woman’s Work — stories, art, and power,” “Changing Museums,” and “Beyond Art.” Each chapter, like carefully curated exhibits, presents the reader with objects and the story behind the objects — ancestral belongings — and each section is like a themed exhibit hall punctuated with stories and poetry that transition to the next door hall.

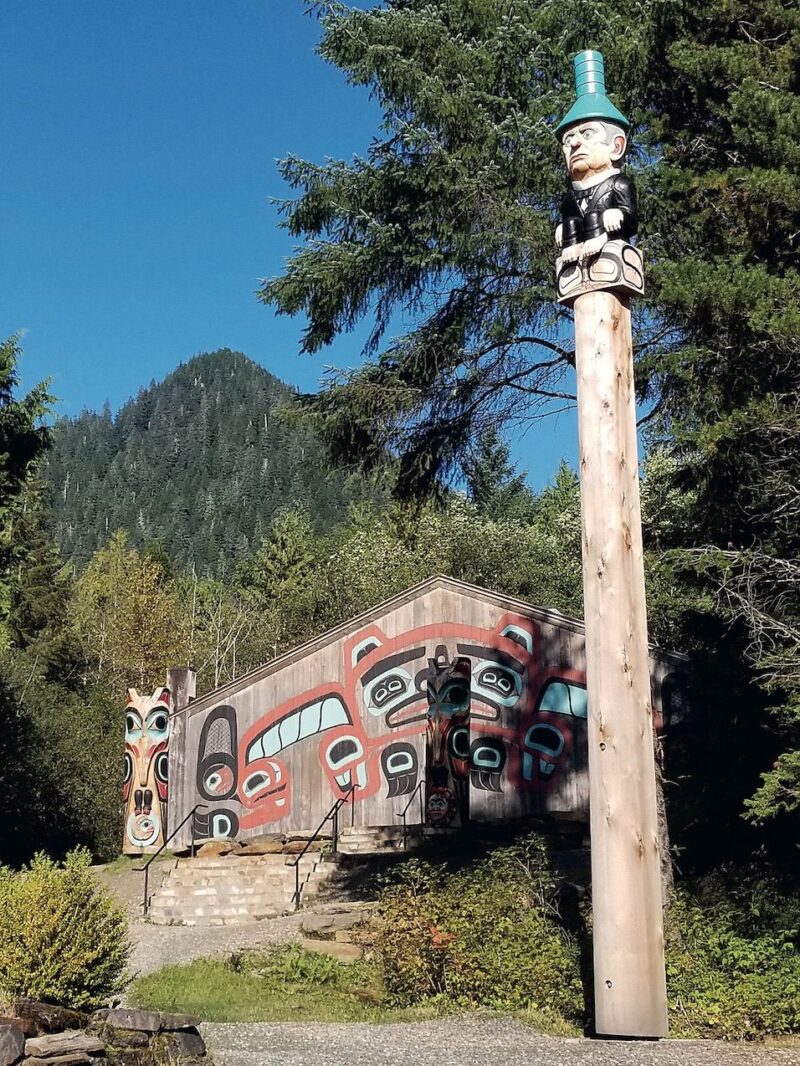

The opening chapter tells the complex and revealing story of the “shame pole” (a revelation to me) representing William H. Seward, who negotiated the “purchase” of Alaska from Russia with no consideration of the original inhabitants. The shame pole represents an unreturned honour debt that Seward owed, along with the non-recognition of Taant’akwáan rights to their lands. There have been three versions of this totem since the original one from the 1880s. The Government of Alaska, unaware of its meaning, paid for the second pole to replace the decaying original in 1941, with the aim of promoting tourism. The last pole was dedicated in 2017, coincidentally when a bronze statue honouring Seward was unveiled outside the State capital – this in an era of toppling colonial “hero” statues. A non-Indigenous tour guide proposed that the shame of debt be paid in the spirit of reconciliation to allow everyone to “move” on. The Taant’akwáan Tlingit refused. As the carver Stephen Jackson, quoted here, suggested, “For what does reconciliation allow people to silence rather than remember, to set aside rather than spur toward justice?”[1]

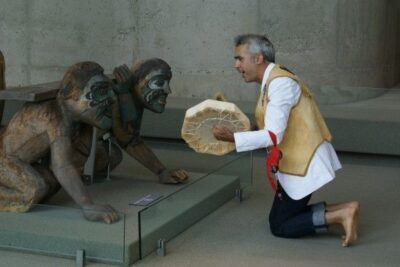

Throughout the book, the reader is encouraged to “unsettle” their own thinking and start to understand Indigenous world views. In the chapter on Peter Morin’s Museum, we read about an experimental exhibit at Vancouver’s Satellite Gallery that displayed the structures — language, baskets, songs, even a kitchen table — representing Morin’s Tahltan culture and knowledge. These structures and objects changed and disappeared over the lifetime of the exhibit, until by the closing date in July 2011, the display hall was empty. Morin explained how his exhibit was to be experienced: “You need to experience all the complexities around this knowledge. You didn’t just get to consume it … you had to work at it.” This is good advice, also, for reading this book.

Lou-ann Neel’s delightful chapter weaves two stories together beautifully: her own journey as an artist and the inspiration she takes from the story of her grandmother Ellen Neel (1916-1966), a Kwakwaka’wakw carver who time and time again broke ground for other women to follow. Haida master weaver Evelyn Vanderhoop of Masset traces her journey to “see” Naaxiin (Chilcat) and Ravenstail blankets, learning from oral and written stories of “sky and cloud blankets” and the spirits embedded in these robes.

A highlight for me was the last section, “Beyond Art,” which helps place the art, the objects, and the ancestral belongings in context. These esteemed items are imbued and surrounded with cultural context, invisible unless you know how to “look” and “know” before you can “see.” Tlingit artists explain the ancestral belongings as “at.óow,” which are inherited clan belongings (such as masks, robes, songs, stories); in Tlingit society, these are inherited by people who are considered caretakers, not owners. Ishmael Angaluuk Hope of Juneau, Alaska — poet, playwright and storyteller — reiterates that there is no Tlingit word for “art” and that the clan houses are containers for the clans’ “at.óow.” Between the introduction, pointing out there is no Indigenous word for art, and this last chapter, one learns the distance between those two words — art and at. óow — and the vast meanings that emerge in the chapters sandwiched in between. Hope’s illumination of art stands out as a good summary: “The art is at.óow,” he writes. “It is alive. It is infused with soul, spirit, and meaning. I like to think that it is the best possible destiny an artist could hope for their art, even what a work of art would want for itself.”

The book is strong with views of northern perspectives. I would like to have seen unsettling views from the Coast Salish whose nations occupy a major portion of the southern coast. This is not a criticism of the contents of the book but rather a reminder that, since contact, in the non-Indigenous view, Coast Salish “art” has always been overshadowed by the “art” of the northern nations and is only just starting to be rightfully appreciated. This historical bias could, in itself, have been a chapter in Unsettling Native Art Histories.

Co-editor Jonaitis provides a concluding section that reviews her fifty years’ experience studying Northwest Coast art and the changing perspectives and increasing involvement of Indigenous artists, elders, knowledge keepers, curators, and writers in contributing, partnering, and leading differing paradigms and cultural narratives.

The many stories and essays in Unsettling Native Art Histories provided me with valuable new teachings and perspectives. I recommend it highly to people of diverse interests in the fields of art, anthropology, history, ethnology, and contemporary Indigenous issues.

*

Retired from Vancouver Island University where she held the position of Director of Research Services, Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa now spends much of her time studying Coast Salish textiles. She holds an MA in Educational Technology and a Master Spinners’ Certificate. She has worked with museums in North America and the UK including the Smithsonian, the British Museum, Pitt Rivers Museum, the RBCM, the Museum of Anthropology at UBC, and the Burke Museum, in helping to identify yarns, fibres, tools, and techniques used to create the yarns. She was instrumental in identifying a rare blanket in the Burke Museum as being made of woolly dog hair. She has given many presentations and workshops on Coast Salish spinning and textiles and has written articles on the subject for magazines such as Selvedge, Spin-Off, and Ply, and for BC Studies on the use of diatomaceous earth in Coast Salish blankets. She lives on Protection Island, in Snuneymuxw territory. Editor’s note: Liz Hammond-Kaarremaa has also reviewed a book by Leslie H. Tepper, Janice George, & Willard Joseph for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] I refer the reader here to Robin Fisher’s thoughtful essay on the removal of totems and statues, “‘The Noise of Time’ and the Removal of History?” in The Ormsby Review (no. 1124, 10 May 2021).

5 comments on “1238 Decolonizing Northwest Coast art”