1202 Hothouse Earth: The future is now

Graeme Wynn reviews four books:

The Imperilled Ocean: Human Stories From a Changing Sea

by Laura Trethewey

Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions, 2020

$22.95 / 9781773101156

*

Passion and Persistence: Fifty Years of the Sierra Club in British Columbia

by Diane Pinch

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2019

$12.99 / 9781550178814

*

Hope Matters: Why Changing the Way We Think Is Critical to Solving the Environmental Crisis

by Elin Kelsey

Vancouver: Greystone Books in partnership with the David Suzuki Institute, 2020

$22.95 / 9781771647779

*

The Citizen’s Guide to Climate Success; Overcoming Myths That Hinder Progress

by Mark Jaccard

Cambridge/ New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020

$22.95 / 9781108742665

Also available in Open Access online here.

*

In late April, as courier companies delivered the four books under review here to my doorstep, an email message from the American Association of Geographers popped into my inbox. Summoning all the gravity it could muster from its 117-year history, and its membership of 10,000 specialists in physical, biological, and social sciences resident in almost 100 countries, this professional society declared itself “uniquely qualified to warn the global community that human and other species habitation of Planet Earth is in extreme danger of collapse due to the impacts of anthropogenic climate change.“ After a further 1,000 words — detailing increasing concentrations of CO2 and methane in the atmosphere, shrinking glaciers, rising sea levels, warming oceans, and “intensified and more costly disasters” of many sorts — the purpose of this “Climate Emergency Statement” was revealed. Having recognized that the “greatest obstacle to climate change mitigation is a lack of political will,” the AAG urged the US President and Congress to action. It was time, they insisted, for new regulations incentives, taxes and education to transition the American economy to zero emissions by 2050, for fear that failure to do so would leave us with “no way to imagine what the world will look like” at that date.

Clearly, we have a problem — and it is not of the imagination. Deeply threatening, this looming calamity is neither new nor easily addressed. Alarms have been sounded for decades, and their urgent tone has grown more strident as the house burns. The troubling spectre of human-induced “climate change” (or “polar-warming” as it was sometimes called) first identified by scientists in the nineteenth century, grew, in late-twentieth century popular discourse into anxiety about “global warming”; that term gave way, in turn, to “global heating” among those intent on signalling the seriousness of continuing changes to the energy balance of planet. By 2018 climate scientists were expressing their concern that “self-reinforcing feedbacks” might produce a “Hothouse Earth” in which reductions in GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions would fail to arrest a continuing rise in temperature. Three years on — with hundreds of fires raging across western North America and still-fresh memories of the heat dome that enveloped British Columbia and drove ambient temperatures to unprecedented levels (approaching 50C in the Fraser Canyon) before the village of Lytton was reduced to cinders — it is tempting to conclude that the “unimaginable” future is now.

Meanwhile, innumerable books and hundreds of thousands of words have been written to chart the scope of the problem, urge people to action, and — ironically if unintentionally — contribute to our collective quandary as they consume paper (and trees), keep power-hungry electronic servers running, are shipped (flown) across continents, and end up, oft times, in landfills. To note only a very few: Jelmer Mommers, a Dutch journalist asks How Are We Going to Explain This? Billionaire Bill Gates offers his view on How to Avoid a Climate Disaster; self-help author and TV presenter David Pogue chips in with a 624 page “practical guide” to avoiding the chaos of climate change; climate scientist Michael Mann and economist Seth Klein would each in different ways go to war against the troubles we face; and Mike Berners-Lee has given us There is no Planet B, delightfully described by a reviewer in the New Scientist as “a sort of Alexa to tell you how to live in a more planet-friendly fashion….”

What then might these four books, each with some connection to British Columbia, contribute in this over-crowded field? Each of them deals in some way with humanity’s relations with Earth. But they form a motley assortment. Broadly (very broadly), they might be associated with what David Beers, founding editor of The Tyee, called future-focused journalism — writing that allows “citizens to imagine and debate alternative futures, and to mobilize support for the versions they support” (SPARC BC News, Spring 2005). Yet their messages are delivered in very different tones. Trethewey and Kelsey adopt a colloquial voice, Pinch steers an unadorned course from past to present, and Jaccard is sufficiently sombre and explicit that I am tempted (in echo of the above-mentioned review of Berners-Lee’s book) to think of The Citizen’s Guide as the most Siri-ous of these contributions.

There is similar disparity in the foci of these books and the scale of their concerns. Pinch maintains a resolute focus on the Sierra Club of British Columbia; Trethewey takes the ocean as her canvas; Kelsey pursues one big idea; and Jaccard is most explicitly focused on the fate of planet Earth. This diversity is further emphasized by the books’ titles, which variously portend calamity (The Imperilled Sea), remind us of the importance of Passion and Persistence, stress the value of optimism (Hope Matters) and suggest how we might prevail over the delusions that hinder progress on the climate file (The Citizen’s Guide). If there is a single refrain running through these works, however, it is about crisis: climate change and biodiversity loss are urgent and existential threats (Kelsey); we are in the middle of a “sixth extinction” (Pinch); “the ocean as we know it today has perhaps a decade left before catastrophic changes take hold” (Trethewey, p. 20); we face a daunting global challenge (Jaccard).

*

“Ocean journalist” Laura Trethewey, who says she “writes true stories that capture our changing relationship with water,” may be familiar to some readers of The Ormsby Review from her time as senior writer and editor for The Vancouver Aquarium’s storytelling website Ocean.org, for which she wrote and produced weekly videos about the sea. The Imperilled Ocean is a collection of seven non-fiction essays about individuals on, in, and engaged with water, together intended to make the point that “the ocean’s story is also our own.” These “human stories from a changing sea,” from “the earth’s last wild frontier” (as marketing copy for the book enthuses), are a diverse lot.

“Ocean journalist” Laura Trethewey, who says she “writes true stories that capture our changing relationship with water,” may be familiar to some readers of The Ormsby Review from her time as senior writer and editor for The Vancouver Aquarium’s storytelling website Ocean.org, for which she wrote and produced weekly videos about the sea. The Imperilled Ocean is a collection of seven non-fiction essays about individuals on, in, and engaged with water, together intended to make the point that “the ocean’s story is also our own.” These “human stories from a changing sea,” from “the earth’s last wild frontier” (as marketing copy for the book enthuses), are a diverse lot.

Trethewey has an omnivorous mind and the journalist’s insatiable curiosity. Chapter by chapter her book offers sprightly, often surprising, accounts of lives touched by the sea. It begins with Pete Romano, “Hollywood’s top underwater cinematographer” shooting a Kanye West music video in a water tank in Los Angeles. Then we cut to barely-experienced BC sailors Fiona McGlynn and Robin Urquhart in their 35-foot sailboat being battered by wind and waves off the coast of Oregon; only later do we learn that they made it, eventually, to Australia. In the intervening pages we read of the rise of offshore sailing as a middle class sport, of Tretheway’s anxieties about sailing out of sight of land, and of her enrolment in a training course for bluewater sailors. We also discover, in an extended personal aside, that Trethewey’s great, great grandfather was the Halifax harbour master when military authorities ignored his policy of unloading explosives outside the harbour and set events on their way toward the infamous 1917 Explosion.

And so it goes. After leaving Fiona and Robin in Sydney, we accompany refugees known as Hassan Basheer (a Syrian) and Mohammed Botwe (a Ghanaian) on separate harrowing journeys across the Mediterranean. Then we join float-home residents facing eviction from the “Dogpatch” in Ladysmith, British Columbia; observe the efforts of volunteers working under the Ocean Legacy banner to remove tons of plastic washed ashore on Vancouver Island’s MuQwin Peninsula [Mquqᵂin (Brooks Peninsula)] where it “carpeted the ground” of nature’s cathedral “like someone had Photoshopped a garbage dump onto the forest” (p. 143); explore a man-overboard mystery in the North Atlantic that dwells on the challenges faced by crew-members on luxury cruise ships; and join a team intent on saving a prehistoric fish (the Fraser River sturgeon).

Each of these stories has some value. Written in a style that reaches for vivid description before thoughtful analysis, giving readers colourful detail about places, circumstances, and occurrences few of them will have experienced, and broadly accessible, they variously charm and intrigue. But this is, in the end, a disparate collection about (some of) those in peril on the sea, rather than a sustained reflection on an ocean imperilled. These are indeed human stories, in most of which the author has more than a “walk-on” part. The rationale for their selection is unclear, and their juxtaposition is sometimes awkwardly arresting. Fiona and Robin, Hassan, and Mohammed were all dreamers, but setting the self-centred carefree indulgence involved in taking a couple of years to sail the Pacific alongside the nightmares of fleeing war zones and persecution, trusting one’s fate to people smugglers, and seeing dozens of fellow refugees drown, tells us much more about the world’s social and economic inequities, and the thin veneer of humanitarian concern, than it does about the “changing sea.”

Trethewey consistently fails to measure the significance of her observations and thus to build a compelling argument. Pete Romano may be worried (or too sanguine) about the possibility that computer-generated imagery will make his craft redundant, and the working conditions of those who attend to every whim of luxury cruise passengers may be trying, but these circumstances scarcely imperil the ocean. Plastics do, and they get some of their due here. But what of ocean acidification, coral bleaching, collapsing fisheries, aquaculture, oil spills, algal blooms, the destruction of coastal habitat, and the atmospheric and ocean pollution produced by global shipping?

Like the ocean, our environmental problems are deep, but Trethewey’s engagement with them is too often surficial and thus superficial. Her all-too-human stories fail to draw out the necessary larger perspective. Her reach for resonant through-lines trends to the banal. “We” have perhaps “been terrestrial animals for too long” and forgotten our “watery origin story” (p. 14). “By the sea, we live in the moment” (p. 21). “What’s off your shores today could be off someone else’s tomorrow” (p. 19). “Taking care of the ocean means taking care of ourselves, too” (p. 211). Recognizing that many environmental problems are a form of slow violence — “too slow, too scattered, too distant” to provoke skeptics to action — she suggests that the ocean can be saved by acknowledging the emotional value of its good health. Statistics, diagrams, video evidence, and rigorous studies are not, it seems, up to the task of convincing humans of the damage we are inflicting on the earth; but expressions of “collective grief” may do the trick (pp. 147-9). This may be near-perfectly in tune with our times, making human feelings, emotion, and “affect” the centre of the story, but I remain unconvinced, and disappointed, by this spumous proxy for a much-needed deep engagement with the imperilled ocean.

*

Diane Pinch’s Passion and Persistence is an altogether different sort of book. Written by a retired psychologist and long-time volunteer with the Sierra Club of BC, this substantial work simply claims to “put together a faithful narration of the challenges” faced, and successes enjoyed, by the club over the last half century. For British Columbians this is an important story, and its significance is nicely captured by Elizabeth May whose brief Foreword urges readers to imagine “a version of It’s a Wonderful Life all about Sierra Club BC,” and reflect upon “how much worse everything would be” had SCBC never existed.

Diane Pinch’s Passion and Persistence is an altogether different sort of book. Written by a retired psychologist and long-time volunteer with the Sierra Club of BC, this substantial work simply claims to “put together a faithful narration of the challenges” faced, and successes enjoyed, by the club over the last half century. For British Columbians this is an important story, and its significance is nicely captured by Elizabeth May whose brief Foreword urges readers to imagine “a version of It’s a Wonderful Life all about Sierra Club BC,” and reflect upon “how much worse everything would be” had SCBC never existed.

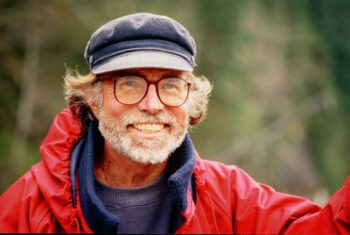

Taking its name, and inspiration, from the Sierra Club founded by John Muir in California in 1892 as part of his continuing effort to preserve the Sierra Nevada (especially Yosemite and Hetch-Hetchy), SCBC came into existence in Vancouver in 1969. Terry Simmons, an American who came to Simon Fraser University for graduate work in geography in the fall of 1968, had spent the preceding summer as a research assistant in the national office of the Sierra Club in San Francisco. Struck by the dearth of similar environmental groups in BC, Simmons contacted local subscribers to the Sierra Club Bulletin, and convened a meeting that led to the incorporation of SCBC to “explore, enjoy and preserve the scenic resources of British Columbia, in particular its forests, waters, and wilderness.” The group was soon active, joining forces with the Save Cypress Bowl Committee that opposed commercial development of that area, and the Run Out Skagit Spoilers (ROSS) coalition to oppose construction of the High Ross dam. It was also instrumental in securing the establishment of Pacific Rim National Park (which spawned a second Sierra Club on Vancouver Island).

The die was cast. The organization went from strength to strength, although legal and organizational arrangements were sometimes rather byzantine. By 1972, when the SCBC had 500 members in Alberta and BC, eastern and western Canadian chapters of the Sierra Club were established; twenty years later the Sierra Club of Canada came into existence with some affiliation to the US organization; a decade on these ties were severed. No matter. In BC, dedicated leadership and the commitment of dozens of volunteers made the club a significant force in most of the province’s major environmental issues.

Pinch provides a useful, well-grounded summary of all of this. Her work rests on close engagement with the SCBC archive as well as interviews with many of those engaged with the club over the years. Her overarching purpose is to chronicle and report and she is a humble scribe: “I have not been able to describe each and every campaign, landmark accomplishment, or leadership initiative, so some may notice gaps here and there, for which I apologize” (p. xii). Much is told, nonetheless. The book is, basically, organized around campaigns in which SCBC played a part: “Campaigns in Northern BC”; “Old-Growth Forests — Conflict in the Woods”; “Campaigns in the Southern Interior”; “Mining Campaigns”; “Oil and Gas issues — Pipelines, Tankers, and Fracking”; “Marine Campaigns — Protecting Oceans and Sea Life”; “The Great Bear Rain Forest.”

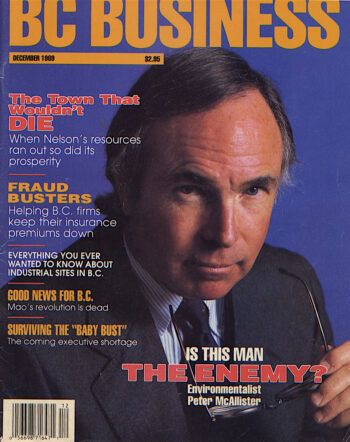

Each of these chapters provides a succinct account of the issues and the SCBC players involved, as well as a useful primer on environmental issues in the province. So one encounters the names and learns of the contributions of many familiar environmental campaigners: Vicky Husband, Peter McAllister, Merran Smith, Katy Madsen, Sarah Cox, Claire Hutton, Colin Campbell, Kathryn Molloy, and Bo Martin among them. Others, redoubtable and influential crusaders with scant connection to the Sierra Club, are passed over (Tzeporah Berman) or given only brief mention (Colleen McCrory). Still Pinch recognizes that the environmental fight was fought by many people on many fronts and attempts to “point out the many instances in which a campaign was successful because of coalitions, alliances and partnerships that were formed at the time” (p. xii).

By the turn of the 21st century, SCBC was beginning to frame the conservation and environmental issues that had been its raison d’etre through “a climate change lens,” and to blur somewhat the ontological divide between humans and nature so central to early preservationist thinking. A new vision statement aspired to the development of an “ecologically sustainable province, which integrates human and economic activity, while conserving the province’s wilderness and biodiversity values” (p. 174). Global warming (and then Indigenous Rights) became central to the SCBC agenda, and the organization claims considerable credit for moving the Gordon Campbell government toward implementation of a carbon tax (although others, including Mark Jaccard, also played important parts). The last words of substantive text in this history are “The Future is Here” (p. 258). In the end, Elizabeth May was close to the mark in suggesting that we would be living in a substantially different place were it not for the work of the Sierra Club through the last half century — and this simple observation feeds conviction that change is possible.

*

Hope matters. It fuels passion and drives persistence — and in Elin Kelsey’s view it is in dangerously short supply in discussions about the fate of the earth. In a nutshell: “Fears about our planet are fuelling an epidemic of despair.” Gloom and doom dominate “how we think, feel and relate to the environment,” seeding anxiety and nurturing a culture of hopelessness. Kelsey, an environmentalist and educator, and adjunct instructor at Royal Roads University, understands the “gravity, urgency, and vast entanglements of the planetary crisis” that we face, but seeks to push back against what she identifies as “the fatalistic belief that it is already too late to act” (back cover and pp. 2-8). In her view, years of forceful insistence on the enormous adverse effects of environmental demise have left us mired in a slough of despond in which it seems as though nothing positive or useful has ever been accomplished. Diane Pinch’s book is of course a modest and welcome corrective to the sense of impotence this creates, but it is written in a very different register. Kelsey’s Hope Matters aims to carry us further, and into the future, not merely by showing what differences have been made, but by crafting “an evidence-based argument” that draws upon the psychological, sociological, philosophical, and spiritual dimensions of hope to celebrate “trends that are heading in positive directions for the planet” (p. 160).

Hope matters. It fuels passion and drives persistence — and in Elin Kelsey’s view it is in dangerously short supply in discussions about the fate of the earth. In a nutshell: “Fears about our planet are fuelling an epidemic of despair.” Gloom and doom dominate “how we think, feel and relate to the environment,” seeding anxiety and nurturing a culture of hopelessness. Kelsey, an environmentalist and educator, and adjunct instructor at Royal Roads University, understands the “gravity, urgency, and vast entanglements of the planetary crisis” that we face, but seeks to push back against what she identifies as “the fatalistic belief that it is already too late to act” (back cover and pp. 2-8). In her view, years of forceful insistence on the enormous adverse effects of environmental demise have left us mired in a slough of despond in which it seems as though nothing positive or useful has ever been accomplished. Diane Pinch’s book is of course a modest and welcome corrective to the sense of impotence this creates, but it is written in a very different register. Kelsey’s Hope Matters aims to carry us further, and into the future, not merely by showing what differences have been made, but by crafting “an evidence-based argument” that draws upon the psychological, sociological, philosophical, and spiritual dimensions of hope to celebrate “trends that are heading in positive directions for the planet” (p. 160).

Insisting that it is hard to be hopeful, to find solutions and to amplify them, while enveloped in a chorus of anguish, Kelsey seeks to ease the burden in fewer than 200 pages of brisk text intended to nurture “the wild, contagious hope that lives inside” us all (p. 184). Her pages carry readers on a heady journey through a daunting array of observations drawn from the literatures of a large handful of academic disciplines (this “evidence-base” is provided in 32 pages of notes). Chapter titles capture the main drift of the argument; “The Power of Expectation and Belief”; “The Collateral Damage of Hope and Gloom”; “Hope is Contagious”; “Stories Change”; “The Age of Personalization”; “We are Not the Only Ones Actively Responding”; “The Strength of Empathy, Kindness and Compassion”; “Trending Hopeful.”

Sympathetic to the claim of Kelsey’s title, I hoped to like this book, and to endorse its message. Certainly it is hard to disagree with many of its specific observations: “The idea that something as complex and extraordinary as all life on Earth could ever be encapsulated by a single grand narrative just doesn’t make sense” (p. 22); “Nature has an astonishing capacity for healing” (p. 72). Others might give slight pause — “fear of failure doesn’t propel you to greatness” (p. 26); “generalized slogans trap us in a fixed state of discouragement” (p. 77) — but work to advance Kelsey’s argument: that hope is better than despair and that it is essential to engaging with “the real and overwhelming issues we face” (p. 11). This is more than important if, as this book suggests repeatedly, children are suffering emotional and psychological anguish because they are convinced that planetary destruction is inevitable and have no idea that other futures are possible.

Kelsey believes that hope derived from such developments as climate emergency declarations; the banning of single-use plastics; reducing food waste; and riding bicycles can carry us forward. Such things need, in her view, to be made widely-known and celebrated, in order to shift the environmental narrative in ways achieved by #OceanOptimism, a social media campaign devoted to disseminating accounts of successful conservation efforts that Kelsey helped to initiate and that has since been emulated by #EarthOptimism and #ConservationOptimism. It is hard to disagree. We desperately need solutions and anything that might encourage them is welcome.

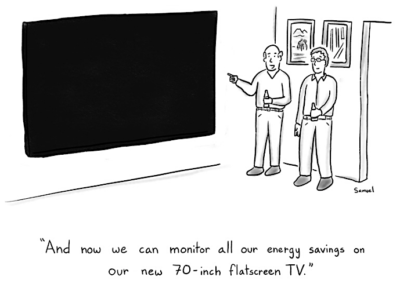

But I am left uneasy by the feel-good message of Hope Matters. As I read this book, its pivotal chapter is the one arguing that we live in an “Age of Personalization.” This, it seems, is defined by the expectation of personalized experiences delivered in an authentic way by the ménage à trois of digital technology, smartphones, and Artificial Intelligence. Individualized feedback tailored to make us “feel valued, appreciated, heard and involved” helps us to “understand how our everyday actions impact the planet” (pp. 105, 116), encourages participation in collective campaigns for action, and spawns a sort of collective wisdom. Perhaps. But situating ourselves in well-informed networks, being appreciated, and being empathetic seem (to me) more likely to enhance a sense of self-worth than to lead to decisive, effective action that averts environmental disasters.

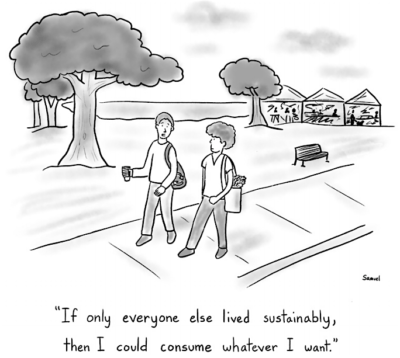

Consider the book’s “Afterword,” which turns on a parent’s concern that his seven-year old daughter cries herself to sleep over the issue of plastic waste. “What can I do?” he asks fellow participants in a workshop on hope and climate change. Answers come thick and fast: “Listen to how she is feeling”; “Share how you are feeling with her”; “Show her a map of all of the places that are banning plastic bags…”; “Remind her that situations can get better”; “Grow seeds and bulbs on the windowsill” and experience the joy of flowers blooming; “Have a sleepover outside”; collect “moments that make her – and you – feel hopeful” (pp. 185-6). All these are fine and good things to do. Anytime. But will they save the MuQwin Peninsula or shrink the Texas-sized mass of drifting slurry in the Pacific? I am reminded of a twenty-year old essay by Michael Maniates, in Global Environmental Politics, sub-titled “Plant a Tree, Buy a Bike, Save the World?” There he mounted a critique of the widespread tendency to “understand environmental degradation as the product of individual shortcomings” and find “solutions in enlightened, uncoordinated consumer choice.” In his view, individualizing responsibility deflects attention away from the nature and exercise of power and influence in society. Although Kelsey believes that the Age of Personalization will yield “a sort of communal intelligence” (p. 120), I worry that personalization and “mindfulness” might deflect us from the real, hard, work ahead. We, humans, are deeply implicated in the environmental crises of our times. Hope matters, but we need more than amorphous, widespread, optimism to realize the better future we need.

*

Few understand this imperative more than Mark Jaccard, a professor in the School of Resource and Environmental Management at Simon Fraser University who has a doctorate in Economics and interests in sustainable energy. He chaired the British Columbia Utilities Commission in the 1990s, advised the provincial government on climate-energy policies in the 2000s and has provided expert testimony to the US Congress and the European Commission, and served on intergovernmental panels addressing issues of climate change. Jaccard’s The Citizen’s Guide to Climate Success reflects all of this experience, and cuts through the platitudes and banalities so unfortunately common in the books of many of those authors who have clambered aboard the climate change bandwagon. Widely and enthusiastically praised by a pantheon of well-regarded experts in the field, who describe it as “a gem,” “essential reading,” “a must-read,” “a huge service,” and a “timely guide,” this book is not the last word on the topic, but stands above much of the recent literature in its respect for hard data, its clear-headed analysis, its embrace of critical scepticism, and its endorsement of the sentiment attributed to Albert Einstein: “Those who have the privilege to know, have the duty to act.”

Few understand this imperative more than Mark Jaccard, a professor in the School of Resource and Environmental Management at Simon Fraser University who has a doctorate in Economics and interests in sustainable energy. He chaired the British Columbia Utilities Commission in the 1990s, advised the provincial government on climate-energy policies in the 2000s and has provided expert testimony to the US Congress and the European Commission, and served on intergovernmental panels addressing issues of climate change. Jaccard’s The Citizen’s Guide to Climate Success reflects all of this experience, and cuts through the platitudes and banalities so unfortunately common in the books of many of those authors who have clambered aboard the climate change bandwagon. Widely and enthusiastically praised by a pantheon of well-regarded experts in the field, who describe it as “a gem,” “essential reading,” “a must-read,” “a huge service,” and a “timely guide,” this book is not the last word on the topic, but stands above much of the recent literature in its respect for hard data, its clear-headed analysis, its embrace of critical scepticism, and its endorsement of the sentiment attributed to Albert Einstein: “Those who have the privilege to know, have the duty to act.”

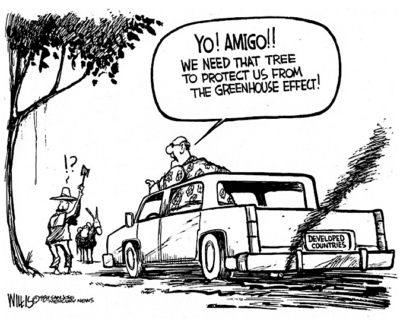

In Jaccard’s view, climate scientists and climate-energy economists have known, for decades, that strong responses to the well-documented patterns of global climate change were both necessary and feasible. But effective action has been (exceedingly) slow to follow. So the question is: “why did it come to this?” Why have we failed, collectively, to respond in sensible and decisive ways to the climate-energy challenge? Why has the steady accumulation of scientific understanding had “negligible effect on the decisions made by individuals, firms, and governments” (p. 8)? The search for answers led Jaccard from his accustomed modelling of energy-economy systems into the realms of political science, public policy, behavioural economics, sociology, psychology, and global diplomacy, and to the conclusion that progress on the climate crises is, and has been, hindered by a number of myths — widely held beliefs that range from blatantly wrong to questionable.

These myths are put to the sword in successive chapters. “Climate Scientists Are Conspirators”; “All Countries Will Agree on Climate Fairness”; “This Fossil Fuel Project Is Essential”; “We Must Price Carbon Emissions”; Peak Oil Will Get Us First Anyway’; “We Must Change Our Behavior”; “We Can Be Carbon Neutral”; “Energy Efficiency is Profitable”; “Renewables Have Won”; “We Must Abolish Capitalism”. Some of these surprise. What does it mean to say that both the need to change our behaviour and the belief that we can be carbon neutral are myths? That we should proceed along the very course that brought us here and that much-touted emissions-reduction targets are fraudulent? Not exactly. Jaccard’s purpose is more complicated and he combines his deep understanding of the issues with an appreciation of the power of stories in informing the public, to tease out his case, often resorting to (perhaps somewhat contrived) anecdotes to advance his arguments. So the problem with behavioural change is that all but its most extreme manifestations (“living like a monk in an abbey”) will have little effect so long as the energy system relies on fossil fuels. The discussion of carbon neutrality is in effect a forensic dissection of the failings of the carbon-offset business. Similarly the question about abolishing capitalism interrogates and rejects, even eviscerates, the contention, of Naomi Klein and others, that “the only path to climate success is to ‘change everything’ about capitalism” (p. 229).

For all its effort to reach a mass audience, this is not an uncomplicated book. Jaccard is too much of a scholar to strip nuance from his analyses. No summary can do full justice to the many facets of this work. But The Citizen’s Guide does offer some “down-home” wisdom and a handful of straightforward suggestions to light the way forward. Be cautious of arguments that place responsibility for mitigating climate change on individuals. These are readily exploited by cynical interests (such as big oil) and can let politicians off the hook. Don’t be distracted by “sideshows” insisting that answers to the climate crisis lie in massively expensive innovations (geoengineering) or radical makeovers of the political system. Focus instead on essential actions and the implementation of transformative policies. For Jaccard these come down to “transforming a few key sectors of our economies, focusing our politicians on a few key policies, and … changing a few key technologies” (p. 248). Put more directly this means moving quickly and decisively, at the national scale, to decarbonize electricity production and transport (phasing out coal-fuelled electricity generation and gasoline/ diesel powered vehicles). These sectors are major contributors of GHG and offer the most readily available prospects for emissions reductions. The challenge is greater for emissions-intensive, trade-exposed industries (but can be met by the development of regulations such as the carbon border tax recently proposed by the European Union). Further, steps must be taken to assist poorer countries to adopt low-emission energy systems. There are hurdles to overcome but they are not insurmountable, and should not induce paralysis.

In the end, Jaccard draws hope from his complex exegesis. In his view, previous energy and technological transitions were driven by the “self-interested decisions” of people seeking options that “performed better” and the process can be repeated. Indeed, he quotes the aphorism usually attributed to Margaret Mead to the effect that all change has been brought about by small groups of thoughtful, committed citizens. Rather than relying upon the amorphous concern of a few to drive change, though, Jaccard seeks to channel and focus the power of the people. They – we — he says, must be able to detect and elect climate-sincere politicians and then pressure them to implement the necessary policies and establish long-lasting regulatory institutions.

We cannot, in other words, afford to turn attention away from the nature and exercise of power and influence in society. It is well to celebrate the influence of individuals and to recognize that, like Bedford Falls without George Bailey, BC without Terry Simmons, Ric Careless, Vicky Husband, Sarah Cox, Peter McAllister and other stalwarts of the Sierra Club would have had a different history. But it is essential to recognize that their efforts were amplified by a wind of popular sentiment, the new social movement known as environmentalism, that gained momentum in the 1960s and placed a premium (as the historian Sam P. Hays had it) on such values as beauty, health, and permanence. It is also well to admire the commitment of volunteers who spend summers picking plastic from remote shorelines to haul out an astonishing twenty-five tonnes of the stuff after six weeks of hard labour. But are such efforts more symbolic than effectual? As Trethewey notes, a study published in Science in February 2015 estimated that eight million tonnes of plastic entered the ocean annually.

Focused on the preservation of forests, waters, and wilderness, members of the Sierra Club could count small steps as progress: a new park here; a logging moratorium there; the cancellation of plans for a gas-burning power station someplace else; all could be tolled as successes on the rosary of environmental protection, even as exploitation continued elsewhere. Lobbying could move governments to weigh the political calculus involved in acting to “save” a particular piece of territory or block a specific development initiative, especially if backed by strong support manifest in club memberships purchased and donations received. Trade-offs were relatively easy to measure and to make.

Today, by contrast, the scale of our most urgent environmental challenges — global heating and despoliation of the oceans — are incommensurable with the effort that individuals can bring to bear upon their mitigation, even if they organize into Sierra-Club-like interest groups. These are what specialists call “global collective action problems” and they are as difficult to address as their name suggests; effective solutions founder on what Garrett Hardin called the “Tragedy of the Commons,” (also known as the free-rider problem). It is highly unlikely that governments around the world will voluntarily and quickly agree to take, together, the steps necessary to decarbonize the global energy system and remediate the seas.

Yet action is imperative. This is why Jaccard, astutely, advocates an immediate focus on decarbonizing electricity and transportation — the least-difficult, biggest-impact strategies to significantly reduce GHG emissions that can be implemented by national governments with little economic downside — while working toward more-difficult-to-realize international/ intergovernmental agreements. Saving the unbounded seas poses a similar if more intractable set of problems. Just as pollutants sent aloft soon span the globe, detritus dumped off one shore is indeed likely to linger in the ocean or make landfall on someone else’s coast in short order. But relatively easy, low-cost, high-impact alternatives to using the ocean as a sink are less readily available than those for remaking the electricity and transportation sectors. Still international agreements have been reached to stay some of the most serious abuses of ocean ecologies (such as moratoria on whaling and fishing), and more should be sought.

None of this will be easy, given the scope of the challenges, the generally short horizons of political concern, the power of fossil fuel lobbies, and the political polarization that has emerged over such measures as carbon taxes. As though to emphasize the point, a recent article in The Guardian (August 4, 2020) described the G20 as “a perfect model of our collective failure to build institutions capable of coping with deep, long-term, existential problems, that cannot be solved by building more weapons,” and pointed out that its members have subsidized fossil fuel production and consumption to the tune of $3.3 trillion over the last five years.

For all that, both Jaccard and the AAG petitioners are surely correct in insisting that solutions must come through the development of legislation and the implementation of regulation. It is indeed vitally important to place these levers of power in the hands of climate- (and environment-) sincere politicians. And here lies the necessity of shifting public opinion, because politicians are unlikely to act against the will of their constituents. Hope matters, because without it there is little incentive to aspire to alternative arrangements. But in the end, conviction, commitment, and action are more essential than hope – and a well-informed public is vital. Electric cars offer certain environmental improvements on gasoline / diesel-powered vehicles, but (as the recent scramble to mine lithium, cobalt, and rare-earth elements reveals) their production is neither environmentally nor socio-economically benign. Rather than resting content with the substitution of one power-train for another, perhaps it is time to reconsider the paradigm of mass car ownership (and many other things). Faced with the ongoing ravages of climate change (and more broadly environmental and social inequities), we comfortable inhabitants of the affluent First World must adjust our expectations and ensure the rapid implementation of less environmentally damaging, and socially and economically unjust, arrangements than those we now know. We need new societal norms to deal successfully with the future that confronts us.

*

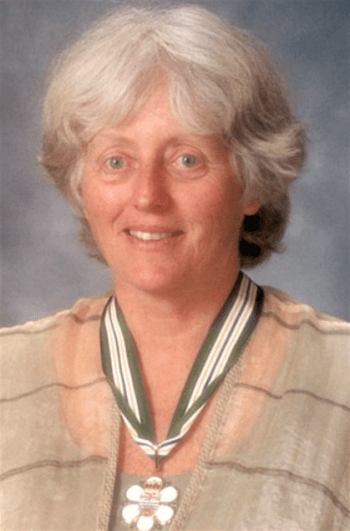

Graeme Wynn is Professor Emeritus of Geography at UBC. As an historical geographer and environmental historian, he served that institution in various capacities including Associate Dean of Arts, twice as Head of Geography and, for six years, as editor of BC Studies. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, he served as President of the American Society for Environmental History (2017-2019) and he is Adjunct Professor (History) in the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Wynn currently serves on the Advisory Board of The Ormsby Review, on the Advisory Board of UBC’s Green College, and as past Principal of UBC’s Emeritus College. Much of his work has focused on Canada, although his interests extend more broadly to encompass much of the so-called British world. He edits the Nature|History|Society series published by UBC Press, and in 2019, under the On Point imprint of UBC Press, published a collection of essays, co-edited with Colin Coates, The Nature of Canada, reviewed for The Ormsby Review by Jenny Clayton. Editor’s note: Graeme Wynn has also reviewed books by Kevin Hutchings, Alison Wearing, Robert William Sandford, Edward Burtynsky, Jennifer Baichwal, & Nicholas de Pencier, Alejandro Frid, Adam Shoalts, Alfred Siemens, and Robert Griffin & Richard Rajala for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

7 comments on “1202 Hothouse Earth: The future is now”

Is it true that none of these books mention population control? It’s hard to imagine a way forward for the species when there are so many of us. Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb, published in 1968, seemed to have a brief impact. Has there been anything since?

Hi Michael. More recently that literature shifted away from “overpopulation” to focus instead on a debate inspired by ecological footprint analysis (i.e., absolute population vs unequal per capita consumption). So, a privileged few consuming much more than the marginalized masses.

Random example: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2009/apr/15/consumption-versus-population-environmental-impact

Thanks for the review, Graeme and Richard M–until now I had only encountered one book of the four.

David B.

Michael: Thanks for the comment. None of the books engages the population question. They are pointed in other directions. Ehrlich has not given up, of course. Here is some of what he wrote in The Guardian in 2018 (fifty years after The Population Bomb):

“Population growth, along with over-consumption per capita, is driving civilisation over the edge: billions of people are now hungry or micronutrient malnourished, and climate disruption is killing people.” True

But without drastic and unacceptable action, population control is at best a too-slow approach to a pressing problem. Even Ehrlich acknowledges this. In the same Guardian piece he said: “To start, make modern contraception and back-up abortion available to all and give women full equal rights, pay and opportunities with men. I hope that would lead to a low enough total fertility rate that the needed shrinkage of population would follow. [But] it will take a very long time to humanely reduce total population to a size that is sustainable.”

Even in 1970s, Ehrlich’s interpretation was challenged. Barry Commoner battled him over the significance of population growth as a factor in environmental degradation insisting that it was not population growth per se, but “polluting technologies and the free market that produced them [that] caused the…crisis,” See Michael Egan,Barry Commoner and the Science of Survival: The Remaking of American Environmentalism (2007)

Good reviews but surely the Jacard book deserved its own review. It is too important to show up only as not a fourth place add-on to this omnibus review.

Howard: Far from regarding Mark Jaccard’s book as an add-on, I would prefer to see it as the culmination, climax, rousing crescendo of a serious reflection on our most pressing dilemma.