1194 Return of The Fire-Dwellers

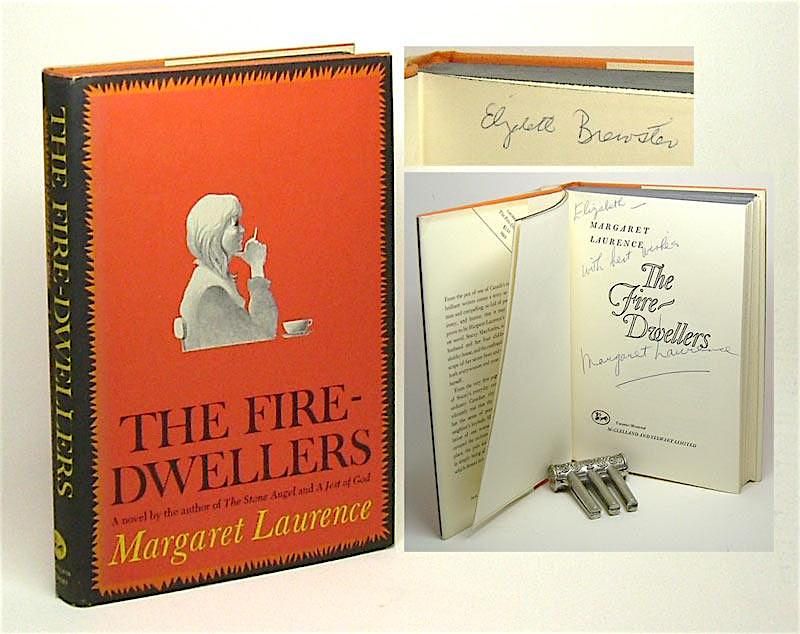

The Fire-Dwellers

by Margaret Laurence

Toronto: Penguin Random House (Penguin Modern Classics, Emblem Editions), 2017

$19.95 / 9780735252837

First published by McClelland & Stewart, 1969

Reviewed by Harper Campbell

*

To read Margaret Laurence’s The Fire-Dwellers (1969) is to see a very different Vancouver from the one that exists today. Well, “see” isn’t really the right word; for the most part, this novel is bare of explicit visualization. Instead, we are put in the mind of Stacey MacAindra, middle-aged wife and mother, and are treated to her constant stream of thoughts and memories. Rather than see Vancouver, we feel it in our bodies, a kind of phantom presence.

To read Margaret Laurence’s The Fire-Dwellers (1969) is to see a very different Vancouver from the one that exists today. Well, “see” isn’t really the right word; for the most part, this novel is bare of explicit visualization. Instead, we are put in the mind of Stacey MacAindra, middle-aged wife and mother, and are treated to her constant stream of thoughts and memories. Rather than see Vancouver, we feel it in our bodies, a kind of phantom presence.

In many ways reading this novel reminded me of Daphne Marlatt’s poetry from the seventies. Marlatt referred to her poetry as “proprioceptive,” that is, not asking the reader to see with her eyes, but to feel from within her body. Her poems, such as those collected in Vancouver Poems (1972), don’t give you a touristic list of visuals, but through their choppy and not easily deciphered flurry of words they bring you physically into the felt space of 1970s Vancouver. That is just what The Fire-Dwellers does, too — it immerses you in the felt Vancouver of 1969 as if it were a pool of water.

So you sense, rather than see, the character of the city. First of all, it’s flat, something pointed to when Stacey refers to “one of the high-risers near the bay” as if it were a novelty. The social culture among Stacey’s set is suburban, based on Tupperware parties, going to the hairdressers, and looking after each other’s kids. The sense of space is probably best articulated in this passage, where Stacey is travelling:

The Chev is parked in front of the house. Stacey turns the key and starts. Before she has driven a block she realizes she is driving too fast but does not slow down. She looks in the rear-view mirror, half expecting to see Mac’s car, but there is nothing behind her at all. She has no idea where she is going. She heads into the city along streets now inhabited only by the eternal flames of the neon forest fires and a few old men with nowhere to go or youngsters with nothing to do. Then through the half-wild park where the giant firs and cedars darken the dark sky, and across the great bridge that spans the harbour, past the shacks dwelt in by the remnants of coast Indians and the apartments and garden-surrounded houses of the well heeled. Along the highway that leads up the Sound, finally and at last away from habitation, where the road clings to the mountain and evergreens rise tall and gaunt, and the saltwater laps blackly on the narrow shore, and the stars can be seen, away from human lights.

We see this, but more than see it we feel the spaces involved.

Another thing about Vancouver in this novel — it is a very white city. Except for one Indigenous woman Stacey meets in the Downtown Eastside, every character is white. As we can see in the excerpt above, with its Indigenous “remnants” and “shacks” at Capilano Indian Reserve No. 5 (Tsleil-Waututh Nation), The Fire-Dwellers features a narrative of “disappearing” Indigenous people. While there is something missing, ethically, from such a vision of things, it does seem to reflect white Vancouverites’ real attitudes at the time — even and especially those of a liberal like Laurence.

Interestingly, the counterculture makes only a marginal, shadowy appearance in Stacey’s world. She befriends a kind of hippie midway through the book, and her fourteen year old daughter, Katie, is attracted to the new popular culture, as any fourteen year old would be. For the most part, we are reminded how small the impact of the counterculture was in some people’s lives, and how strong the continuity mainstream culture — especially consumerism.

If anything defines Stacey’s world, it’s 1960s consumer culture. She relentlessly reads the beauty magazines at the hairdresser’s, goes to those Tupperware parties at her friend’s house, and in an extended subplot, her husband Mac takes a job selling vitamins that involves them in endless consumerist hokum. In many ways this aspect of the novel reminded me of Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman, also published in 1969.

While the counterculture never takes centre stage, it exists as a reproach to the way Stacey and her family live their lives. A major theme of this book is communication. Stacey is miserable largely because she can never truly communicate with the people in her family. Her husband, Mac, is brooding and tense. Nothing she says to him ever seems to come across right, and they bicker constantly through the novel. Her kids, too, much as she loves them, are in a way inscrutable to her. She recognizes that she is missing out on their real lives, unsure of what they are thinking about or what matters to them.

The failure of communication is somehow tied to the Protestant Christianity of Stacey and Mac’s parents. It seemed to require so much suppression of feeling and denial of affection. Both Stacey and Mac remember their childhood homes as cold and uncommunicative spaces, spaces marked by silence and unspoken wounds. Stacey is dying to break through this wall of ice and really be able to communicate with the ones she loves.

In a way we are witnessing, with Stacey and her family, the beginnings of our current obsession with communication. Nowadays people find relaying their feelings an enjoyable and honourable pursuit, something to spend a great deal of time and money improving. Indeed, Vancouver and the West Coast in general seem to have led the way in Canada to a culture of emotional honesty.

Stacey’s family trouble is also explicitly tied to an emerging feminist consciousness. Through Stacey’s eyes we see just how gendered the breakdown of communication is in her family, with Mac’s silent stoicism a prime example. And we see Mac trying to enforce a similar kind of masculinity on his sons that is vocally homophobic. Stacey’s family starts to resemble ground zero for the massive social changes that began in the 1960s.

It’s tempting to look back at the breakdown of 1960s attitudes as leading inevitably to our own. People’s uncommunicative families were driving them crazy, and now we have abundant emotional communication, with every phone conversation ending in “I love you.” Gender roles and their production in family life were also driving them crazy, and now we’ve made room for much more variety of gender expression. We are the solution to the problem they faced. But by retroactively turning the flow of history into a lazy river with no sharp bends, we minimize the eventfulness of the time and the real possibilities that were in the air.

After all, in 1970 the social critic Paul Goodman (1911-1972) referred to “a political, cultural, and religious crisis that must be called pre-revolutionary” in America. In many ways we have assimilated the turbulence of those times into an essentially uneventful story, and so we are cautious of a word like pre-revolutionary. But it speaks to the intensity of the disillusion people felt with the phoniness of consumer culture, the violence of the government, and simply the untenability of the status quo. As Goodman notes later in New Reformation: Notes of a Neolithic Conservative, his utopian insights were popular in Canada at that time:

Since I am often on Canadian TV and radio, I tell it to the Canadians. If they would cut the American corporations down to size, it would cost them three or four years of high unemployment and austerity, but then Canada could become the most livable nation in the world, like Denmark but rich in resources, space, and heterogeneous population, with its own corporations, free businesses, cooperatives, a reasonable amount of socialism, a sector of communism or guaranteed income as fits modern productivity, plenty of farmers, cities not yet too big, plenty of scientists and academics, a decent traditional bureaucracy, a non-aligned foreign policy.

Violence is another main theme of the novel. Stacey’s world is full of a violence that is normalized and never leaves the picture. It happens in her family, on the street, in stories with friends; it comes over on TV and radio in stories of Vietnam and riots in American cities. We see it in the Downtown Eastside when Stacey visits there; we see it in her memories of small-town Manitoba. The novel is permeated with a stain of violence that seems inescapable.

Laurence seems to be pointing to a sense of a status quo breaking down. People’s lives just don’t seem to make sense anymore. Stacey has no idea how she ended up in this family situation, living this life, and is dying to escape if she could only do so without letting anyone down. The other characters feel the same, in their own way, and the world as a whole seems to be on the brink of collapse.

Interesting as these themes are, they are not always well incorporated into the text. The thematic content frequently works against the credibility of the realism. That’s true in the subplot about Stacey’s husband Mac and his new job. The phoniness of his work culture defies description and brings the novel itself down to the level of a cartoon. It’s also true about the character Luke, who is something of a hippie. His scenes work and he’s far from being a cardboard character, but if it weren’t for his contribution to the themes Laurence pursues, it’s hard to see why he would be in the novel.

All things considered, though, The Fire-Dwellers is very well put-together. Stacey and her world have a kind of solidity which makes them compelling even when the plot is not going anywhere in particular. It’s a solidity that is not always vivid, at least in the sense I usually think of the word; characters don’t snap to life with unforgettable liveliness. Instead, the characters are really there; they were there yesterday and they will be there tomorrow. Her craft in character-building allows me to put my trust in Laurence as a novelist while she winds me through the various stages of the novel.

The form itself is experimental in an interesting way. Most of the novel is made up of Stacey’s internal monologue, much of it self-critical. She is always appraising and reappraising the people and events around her, trying to make up her mind about them. Dialogue appears without quotation marks, seeming to make it an appendage to the internal monologue. Other sections set in a different font depict images from Stacey’s memory and imagination. They seem not to come as verbalized sentences, but as transcriptions of wordless images that Stacey sees. If all this sounds a bit confusing, it’s handled in a very confident way that makes it easy to fall in with.

Here’s an example of how the novel reads. This is from one of the more experimental parts, the family at breakfast:

Come on, you kids. Aren’t you ever coming for breakfast?

THIS IS THE EIGHT-O’CLOCK NEWS BOMBING RAIDS LAST NIGHT DESTROYED FOUR VILLAGES IN

Mum! Where’s my social studies scribbler?

I don’t know, Ian. Have you looked for it?

It’s gone. I gotta take it to school this morning

Well, look. Katie, have you seen Ian’s social studies scribbler?

No, and I’m not looking for it, either. If he wasn’t so

Stacey, the party starts at eight tonight. Be ready, eh?

Sure, yes yes of course. Duncan, eat your cereal.

I hate this kind. Why do you always buy it?

You say that about every kind I buy. C’mon.

WORD FROM OUR SPONSOR IF YOU HAVEN’T SEEN TOOLEY’S NEW SHOWROOM YOU’RE IN FOR A REAL COOL SURPRISE

As you can see, the form takes unusual risks and breaks conventions, but doesn’t ask you to stop and puzzle out what the heck is going on.

Although The Fire-Dwellers is very readable, it’s not always pleasant to read. By the two-thirds point in the story, Stacey is so mired in her crises that opening the book sometimes felt like entering an airless room. And because we are exposed to all of her self-criticism, the book can put you in a similarly negative state of mind. Indeed, I think some readers might find all this too upsetting to enjoy.

But I do recommend this book. A strong imagination underpins the events of the story, giving it a heft that is hard to describe in a short review. For all its depictions of stagnancy it never leaves the reader loitering around. To anyone from Vancouver, it will have a special interest as a snapshot of a turning point in the history of the city. It sheds light on people’s lives from the city’s past, and it will bring back memories for anyone who remembers the way things were in those pre-revolutionary days. It does so all the better because it succeeds as a novel.

*

Harper Campbell has published poetry in Salish Seas: An Anthology of Text + Image (Aboriginal Writers Collective West Coast, 2011), an essay in The Salt Chuck City Review (volume 1, 2019), and translations of the Indonesian poet Chairil Anwar in Columbia Journal (2021) and Ezra (forthcoming). He has an honours degree in philosophy and Asian studies from the University of British Columbia. Editor’s note: Harper Campbell has also reviewed books by jaye simpson and Joshua Whitehead for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “1194 Return of The Fire-Dwellers”

An amazing piece — it brings a modern eye to an older book that, after so many years, remains ‘modern’ in some of its own ways.