1089 A lifetime of care and medicine

Improbable Journeys: From Crossing the Himalayas on Horseback to a Career in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

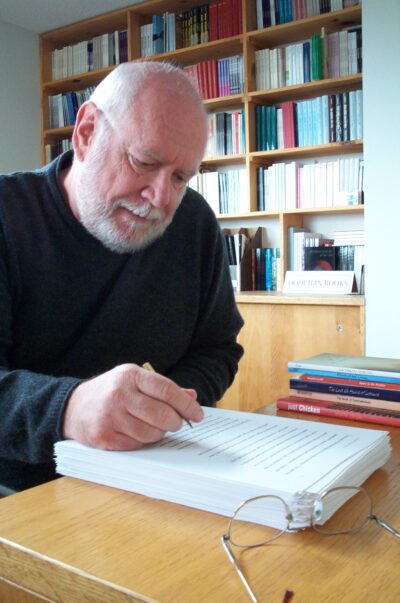

by Dr. Bernard A.O. Binns and Ron Smith

Oakville, ON: Rock’s Mills Press, 2020

$29.95 / 9781772441932

Reviewed by May Q. Wong

*

Editor’s note: for a subsequent review of Improbable Journeys by John Kenwright, see The Ormsby Review, June 15, 2021 — Richard Mackie

*

Dr. Bernard Binns’ memoir, co-written with Ron Smith, is partly a travelogue and mostly a commentary on the teaching and practice of medicine. It is a chronological autobiography. The book takes the reader on a journey through parts of the world, many of which Binns visited in his childhood, that few of us will ever have the opportunity to visit. Even with today’s modern transportation, destinations such as the Falkland Islands, the ancient Silk Route from Pakistan to Chinese Turkestan across the Himalayas, Nigeria, and Uganda might be more suited to an adventure voyager, particularly in the ways that the Binns family travelled.

Dr. Bernard Binns’ memoir, co-written with Ron Smith, is partly a travelogue and mostly a commentary on the teaching and practice of medicine. It is a chronological autobiography. The book takes the reader on a journey through parts of the world, many of which Binns visited in his childhood, that few of us will ever have the opportunity to visit. Even with today’s modern transportation, destinations such as the Falkland Islands, the ancient Silk Route from Pakistan to Chinese Turkestan across the Himalayas, Nigeria, and Uganda might be more suited to an adventure voyager, particularly in the ways that the Binns family travelled.

Binns’ acute visual, auditory, and olfactory memories provide an abundance of detail presented in Ron Smith’s understated and straightforward writing style that keeps the narrative flowing.

Dr. Pat Binns, referred to as “Father,” was a general practitioner who made impulsive decisions that led to a life of adventurous travel and a varied medical career. As jobs in Depression-era Britain were scarce, Father applied to the Colonial Office, searching for jobs around what was still the British Empire. It seems he proposed to Mother, partly in the hopes of being posted to the Falkland Islands, where married couples were sent.

Ada Binns, referred to as “Mother,” was a “strong willed and independent woman (p. 56),” trained as a surgical nurse and midwife, who took their peripatetic life in stride. Unfortunately, it seems Mother never worked outside the home again. She described the “…Falkland Islands as the most depressing place she had ever lived” (p. 4). The land was, and still is, barren and populated with vastly more sheep than people. There were no roads to traverse the island, so it was a lonely place to live. No trees provided shelter from the almost constant wind. It was in Port Stanley where Bernard was born on April 2, 1934. The family did not extend their two-year term.

While Bernard had no memory of his time in the Falklands, “[what] did surprise me was my anger when I heard Argentina had invaded the Islands in 1982. No matter how irrational my attachment now seems, this violation brought home to me how important one’s birthplace is and how sensitive people can be about it (p. 5).” This was a sentiment he would understand later in his life, working with the Inuit Peoples in Canada’s north.

After a couple of years of working back in England and almost investing in a partnership in a general practice, Father made another impulsive decision and signed up as a commissioned officer in the Indian Medical Service. Father travelled on ahead, while Bernard and his mother stayed behind to await the birth of his sister, Marjory. The family of four moved to India in 1938 and first lived in the southwestern coastal city of Kannur.

“My first vivid memory of India was of nearly drowning in the ocean (p. 7).” He describes the incident in detail. When he escaped the clutches of the sea, he told his mother that he got his hair wet because a wave had knocked him over. “At the time, I was between five and six…. I didn’t appreciate the danger. I remember thinking that if I’d told my mother the full story I wouldn’t have been allowed to paddle on the beach and that was something I liked doing (p 8).”

He also recalls in detail the comfortable house they lived in and the easy lifestyle they enjoyed, until the onset of the Second World War in 1939. When Father was shipped to the Middle East to take care of the troops, the family was moved to Bangalore, where they lived in more crowded conditions. Father became very ill and was sent back to India from the war to recuperate.

Bernard also had to attend school. His first few experiences were not positive. Even when he was privately tutored, he admitted to learning to ride a bicycle but not to read and write. He had a “mild form of dyslexia” that was not diagnosed until later and had difficulty with reading and writing throughout his life. He overcame the limitations by being very disciplined. Later on, when studying medicine, he writes, “I found it difficult to grasp this material from reading the written descriptions in Grey’s Anatomy, the student’s anatomy bible, in spite of its diagrams. I learned most of my anatomy in the laboratory actually dissecting out the structures and seeing them in three dimensions. My visual memory and logical thought processes saved me (p. 201).”

Bernard also had an ear for languages. While in India at the age of seven, he learned to speak Malayali, the local dialect, from spending time with the household servants and their children. He translated instructions from his mother to the gardeners, caregivers, and cooks. He also became fluent in Urdu, Hindi, and Turki, the language most commonly spoken in Kashgar. His fluency was such that, at thirteen, he interpreted for his parents at social functions held at the Russian Consulate. At one point, his parents had to insist that he and his sister Marjory speak to each other in English in the house so they wouldn’t lose the language of their birth. As an adult, he also learned some Swahili and Ugandan dialects and knew what his patients were saying, “… sometimes with a better understanding than the interpreters (p. 360).”

A six-week journey from Abbottabad, now in Pakistan, to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, now known as Xinjiang, across the Himalayan Mountain range, offered young Binns “… the most dramatic vista I had ever seen (including all the mountain ranges in Europe and America I would see over the next seventy years)” (p. 44). The family were piggy-backed across a river; travelled with caravans, variously riding horses, donkeys, camels, or yaks; walked across a wood and rope suspension bridge watched over by an elderly gate-keeper; and crossed three mountain passes and a glacier. This was one of the northern Silk Routes that carried “spices and cloth between India and China and then on to Europe” (p. 36) – a route taken by Marco Polo in the late 13th century.

The return trip from Kashgar via India to England after the war was perhaps even more suspenseful. The Binns family travelled an old caravan trail through Ladakh (“Little Tibet”), which had been seldom used, and they had to depend on the memory of a “very old man” who had not travelled the route in over ten years. They were shot at by a Chinese patrol that was chasing bandits in the area and suffered headaches from high altitude. Yet, Bernard was still able to marvel at the colourful dress and decorations of the men and women of Ladakh.

Young Binns saw many sights that will be familiar to nomads and traders, from the towering mountains to the colours of the flora. His historical travelogue conjures up adventure, the life-threatening danger of instant death from falling down a crevasse, or drowning from rushing glacial ice water, mixed with the realities of sharp unpleasant odours of animals, unwashed human bodies, repetitive meals, and hard sleeping surfaces. The Binns’ journey calls to mind characters whose hardiness, daring, and romance contrast sharply with this “ordinary” English couple and their two young children.

Within six months of Bernard starting high school in England, his parents accepted a posting in Northern Nigeria, where they stayed for ten years (1948 to 1958). There, they lived in six different cities, and Bernard visited them during three summer holidays. After returning to England in 1958, his parents never travelled out of the country again. Father worked as a school medical officer until almost age 90 and taught local children how to play the flute. Mother died at age 70.

On Bernard Binns’ first visit to Nigeria at the age of sixteen, his father took him on rounds to see patients, and it was then that Bernard first considered becoming a doctor. While observing him, “I was surprised and impressed by how much a patient’s answers formed a part of my Father’s assessment. This collaborative approach to diagnosis was to influence my own practice of medicine in future years” (pp 151-152).

Bernard studied medicine at his father’s alma mater, Guy’s Hospital in London. He met his future wife Elaine May Parker at the London boarding house where they both lived. She was a year ahead of him in medical studies at the Royal Free Hospital. They were married on March 1, 1957, when she had one more year, and he had two more years of studies to complete their degrees. Bernard and Elaine subsequently had three children: Helen, Kathryn, and Patrick.

Bernard describes his medical school training. Noting how certain lecturers were more effective than others, he later adapted those styles to his future teaching roles. As a clinician and professor, he learned the importance of patience, listening, and seeing people as individuals in diagnosing patients, as well as in helping students to learn.

After completing their academic courses, Bernard and Elaine worked at various short-term internships (houseman), but in different parts of the country. Bernard’s offer of an overseas internship at Grace Hospital in Winnipeg (1960-1962) provided a lucrative solution and allowed the family to be together. Elaine also found part-time work after the birth, shortly after their arrival in Canada, of their second child. Bernard recalls the pleasure of his first taste of cinnamon buns at the Toronto airport, followed by waffles with maple syrup on the plane trip from Toronto to Winnipeg.

He recalls the family’s first really cold winter in Winnipeg:

The cold had its own beauty. On calm days ice crystals hung in the air. When the sun shone on them they refracted the colours of the rainbow…. Winnipeggers took some pride in the fact that their temperatures usually ranged between -40 degrees F. (-40 degrees C.) in winter and +40 degrees C. (+110 degrees F.) in the summer. I found both extremes hard to tolerate. The saving grace was that it was very dry (p. 291).

As a newly-qualified immigrant doctor, Bernard reflected on the differences between the British and Canadian systems for teaching doctors:

Over time I realized that Canadian-trained residents and interns were more academically orientated than I was. They tended to rely on laboratory investigations more than the actual hands-on physical examinations of patients to make decisions about treatment. While their undergraduate training was much less practical than mine, their theoretical teaching was much more extensive. Our respective programs were the same length in time, but patient contact and responsibility for patient care was much less in Canadian medical schools. Their internships covered a broader range of medical disciplines than mine had in the UK – for example, everyone spent time doing maternity and paediatrics. I wondered if these differences had any long-term consequences in our roles as family practitioners (p. 298).

It might have been Bernard’s own difficult birth – he was premature, had presented hand and arm first, requiring an awkward forceps delivery, and came out with a broken collar bone and ribs – which influenced his decision to obtain specialized training in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Deciding that he would receive more in-depth practical experience in the UK, he returned to train at Oxford under the supervision of two well-known gynaecologists.

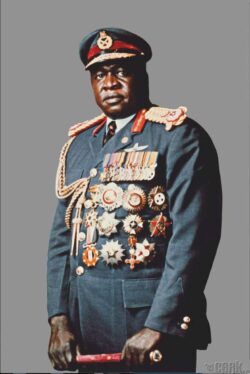

Armed with his new specialist medical credentials, the family’s next adventure was in Uganda (1965-1967). They arrived shortly after the country had gained its independence from Britain. Bernard met the Chief of Staff of the military, Idi Amin, the future dictator, at an event to celebrate the opening of a new military airport:

I remember him as a very large, ugly man, decked out in his uniform, who looked down on me from a great height. Although this occurred before he took over the country, I could sense his impatience, intolerance, power and dominance…. We shook hands, mine disappearing into his enormous hand before he moved on to another guest. I was relieved when I felt I could politely leave the party (pp. 374-375).

During this posting Elaine couldn’t practice, but she kept busy with the education of their three children, supervising the house and garden staff, marketing, learned to play golf, and organizing the social events for ex-pats at the golf club. The family also enjoyed excursions to see the natural wonders of Africa.

Poor nutrition and an abundance of tropical diseases and parasites caused many obstetrical complications for Ugandan women, as Bernard Binns recalls:

Many of the obstetrical problems that these women presented can only be read about in classic works on obstetrics dating back over hundreds of years…. Often the patients arrived at the hospital in dire straits, not only with problems related to their labour, but with other complicating factors such as severe anaemia, infections, malnutrition and treatment by some very potent noxious agents given to them by witch doctors. I didn’t doubt that many witch doctors were very knowledgeable and helped a lot of patients in the bush. Yet their remedies were doomed when it came to obstructed labours and did more harm than good…. [However], the women showed remarkable resilience and were able to recover from severe trauma, anaemia and infections (pp. 364-365).

When Bernard learned that it was unlikely that a specialist would replace him when he left, he decided that his best chance to improve the quality of obstetric care was through teaching at the midwifery school. All the midwives had trained as nurses. He taught the students about “…medical problems which affected pregnancy, labour, delivery and the postpartum period…(p. 375).”

Ugandans made do with the tools on hand. Bernard recounted the story of the town’s mechanic. “Gulu had a Shell petrol station with a mechanic,” he writes. “The standing joke was that he had only three tools: pliers, a screwdriver, and a hammer. However, he was quite competent and managed to keep most of the cars, trucks, motorcycles and bicycles in the area on the road. He certainly had no trouble replacing my broken windshield” (p. 356). Like the mechanic, Bernard’s creative lab technician at the medical clinic created a much-needed blood bank despite the lack of sophisticated resources.

When his contract was completed, the family returned to England for what turned out to be a brief stay to reconnect with their extended families. It was during this time that Elaine found an interest in anaesthesiology. In 1967, Bernard was offered a job in London, Ontario, where he completed his practical requirements to write the Canadian board exams and where Elaine was accepted as a resident in anaesthesiology. But there were few jobs in private practice in London, and Winnipeg beckoned once more, as Binns recalls. “And so, in 1968, at the age of thirty-five and ten years after qualifying in medicine, I was now a consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist in Winnipeg, Canada” (pp. 397-398). This time, he worked at the Abbott Clinic and at several hospitals, including at the modern facilities at the New Grace Hospital, where Elaine also worked. She would retire from there as head of the anaesthesiology department.

While in Winnipeg, Binns writes, “[my] gynaecological expertise in the areas of pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, myomectomies for fibroids in young patients, and some other unusual gynaecological problems, such as transexuals and gender anomalies, gradually became known and became a significant part of my practice” (p. 399).

Financial cutbacks in the province influenced the way he wanted to practice. Bernard took a cut in pay to re-train in obstetric and gynaecological infectious diseases and teach it at the University of Manitoba medical school. In 1980, it was while training with an infectious disease specialist in San Francisco, that one of the first cases of the transmission of the AIDS “virus from a mother to the in-utero fetus was recognized (p. 420).” Bernard learned the strict isolation techniques and protocols for treating patients with AIDS, which he put to use when he returned to Winnipeg.

During his ten years as Assistant Professor at the University of Manitoba medical school, he introduced a number of new innovations including gynaecological laparoscopy, improved ultrasound scans, and new areas of research and treatment for endocrine infertility and IVF (in vitro fertilisation), herpes and HPV (human papilloma virus).

He had also worked with Indigenous communities in the Canadian north. “One of the most transformative responsibilities I had… was caring for patients in [Rankin Inlet], in the Keewatin area of the North West Territories, along the west coast of Hudson Bay…. Faculty took turns going up to these northern communities to see patients, perform minor surgery, and teach the nursing staff and other health-care personnel” (pp. 427-428).

Here we see an experienced gynaecologist providing his wide experience to Indigenous communities:

… I felt strongly that we had a responsibility to care for people in their own communities…. Previously, expectant mothers were transported south and all babies had to be born in Manitoba, against the wishes of the parents who would have preferred their children to be born on the land of their ancestors. More recently, “[a] large medical centre had been built that was serviced by local doctors and midwives. This meant that women could have their babies in town…. [Immersing] myself in the culture and problems of the people in the Keewatin area brought me the greatest joy (pp. 450, 452, 457).

In 1992, Bernard and Elaine retired from full-time work in Manitoba and moved to Vancouver Island. During the past 20 years, the couple have divided their time between Canada and New Zealand, where Bernard worked part-time as an obstetrician-gynaecologist consultant and Elaine worked as a locum in anaesthesiology in Whakatane, on east coast of the North Island. Elaine Binns died January 24, 2021 at Whakatane Hospital, New Zealand, with Bernard at her side. She had just seen the published book, which was dedicated to her.

As a final word on his philosophy of medical practice, Bernard says: “…[In] New Zealand…the patient’s story remains a critical part of the diagnostic process and treatment, reminiscent of our training and early practice in the UK…. Medicine is still a relationship, an art, practiced between people, people who trust and depend on each other in a community of peers (p. 459).”

Bernard Binns’ patients and students have benefitted from this lifetime of dedicated practice that extended from a childhood in the last days of the British Empire to modern medical education and practice in England, Uganda, Canada, and New Zealand.

*

May Q Wong researches and chronicles the extraordinary in ordinary people. A graduate of McGill University, she holds a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Victoria and retired from the BC Public Service in 2004. Her first book, A Cowherd in Paradise: From China to Canada (Brindle & Glass, 2012), concerns a Chinese couple separated for half of their 50 year marriage, and the impact of Canada’s discriminatory laws on their family. City in Colour: Rediscovered Stories of Victoria’s Multicultural Past (TouchWood, 2018) (reviewed by Tom Koppel) concerns the diverse range of immigrants and their contributions to Victoria. In addition to reading, writing, and speaking to groups about her books, May creates useful and beautiful things with knitting and sewing needles – the latest being hand-beaded face masks. Editor’s note: May Wong has also reviewed books by Patrick Saint-Paul, Ian Greene and Peter McCormick, Beverley McLachlin, Graeme Taylor, Dukesang Wong, Henry Yu, Mei-Li Lee, Catherine Clement, and John Price & Ningping Yu for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “1089 A lifetime of care and medicine”

I could not put this book down, truly delightful! What a life my neighbour has had! Thank you Bernie & Ron.

Thanks for your kind and generous comments, Terri. Much appreciated.

I “paced out” my reading of the published version of Improbable Journeys in order to enjoy it thoroughly. I am very impressed with how Ron filled out the story while retaining the natural voice of my father.

Truly well done!