1079 Motherhood and talking plants

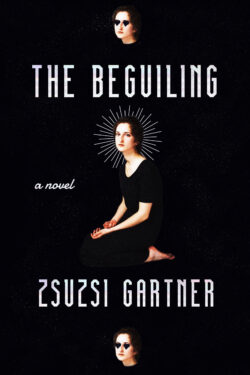

The Beguiling

by Zsuzsi Gartner

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (Hamish Hamilton), 2020

$29.95 / 9780735239357

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

Motherhood is difficult and often unrewarding. Before I am besieged with outrage at how motherhood offers a profound experience unlike any other, please reread that sentence: I said often, not always. A statement need not be unequivocal to be treated as such. For example, dissent has a delicious way of feeling virtuous and sanctimonious, but dissent is not virtue.

Motherhood is difficult and often unrewarding. Before I am besieged with outrage at how motherhood offers a profound experience unlike any other, please reread that sentence: I said often, not always. A statement need not be unequivocal to be treated as such. For example, dissent has a delicious way of feeling virtuous and sanctimonious, but dissent is not virtue.

The Beguiling by East Vancouver writer Zsuzsi Gartner has a fantastic premise and awesome writing to boot. Although “awesome” has become, in the age of increasingly rote hyperbole, a word taking the place of formerly serviceable words like “fine”—a brainless way to express affirmation—when I say that Gartner’s novel is awesome, I mean that it is awe-inspiring. Lucy, the protagonist, becomes a magnet for confessions after the unsavoury death of her beloved cousin, Zoltán. Gartner’s opening line is a question: “Did it really all begin with that wretched business concerning my cousin?”

Lucy becomes privy to fantastically weird and intimate confessions including but not limited to: a pug hell-bent on enacting revenge on its owner’s lover; hermaphroditic plants identifying with Shylock from The Merchant of Venice; a nurse who confesses to having switched two babies on purpose to allow the sickly baby to be taken care of by the wealthier family (a case of unethical ethics, if you ask me); a woman who fakes cancer and inspires Lucy to briefly and disastrously feign a cancer scare herself to Pippa, her high-achieving daughter. Lucy is neither a Stepford mother, nor is she anything like Sheryl Sandberg (thankfully); in fact, she is not even the primary caregiver. Lucy is irreverently candid in her experiences as a mother: “Becoming a mother had just made me want to kill people” (p. 122).

I don’t believe that literature is a panacea for an empathy deficit, nor do I think literature should be tasked with such a grievously large responsibility it is doomed to fail, but I do think literature has the ability to help us realize that our sordid conceptions of ourselves as uniquely perverse and scarred are widely shared, even borderline universal. Lucy’s own admissions seem relatively sparse and guarded in comparison; we are told just enough without having to rely on too much inference. In other words, Lucy’s appetite for the confessions of others and how she views them—generally, quite sympathetically—is an effective way for the protagonist to learn about Lucy obliquely.

Gartner is canny with her commas: omitting them where they would be customary, e.g. “In some oblique way they blamed the movies” (p. 6) and deftly employing one near the end of a sentence with a final punch of a verb choice, e.g. “The girls always passed quietly by, unmolested” (p. 111).

When it comes to describing Gartner’s writing, I become uncomfortably close to genuflection. I relished Gartner’s writing, sentences like “Zoltán’s scrotum had been ravaged until it hung like the derelict flag of a failed nation” (p. 21) and “The first time he dared lick them an instant hard-on pressed so theatrically against the crotch of his Levi’s [that] Martin thought it would torpedo through the fly, the teeth of the zipper tearing his dick to shreds” (p. 108). Gartner is not one to shy from phallic violence, or really, from anything. She writes about penises and sex unsentimentally, a trenchantly detailed insouciance that is often laugh out loud funny: “She had pictured the small defeated man’s cock as a limp tube encased in a wrinkled foreskin, but it’s a robust and tawny mushroom. As Eva sucks him off he continues to whimper, wiping uncannily large tears from his eyes. A couple of them splash onto her bent neck and trickle warmly down her spine” (p. 170). In this novel, even a tumescent penis is more comical than frightening, mere anatomy pathetically hoping—expecting—to be serviced.

Lucy is comfortably literate. She corrects her mother’s misconception of Frankenstein as the monster. Her mother’s response? “Nobody cares how smart you are” (p. 19). Of doctors, Lucy thinks, “Doctors and their lack of a classical education, it’s truly disheartening” (p. 257). The Beguiling is a zing to read—often unique, often humorous, and Gartner does not shy away from alliteration, either, e.g. “She looked queasy, as if she’d just slurped back a super-sized serving of impossible mother” (p. 97).

I am reluctant to say Lucy is a subversive female protagonist, as “subversive female protagonist” has become stripped of its original meaning insofar as it has come to mean the following: not being maternal; being promiscuous without waiting for a man to call; identifying as any orientation that isn’t heterosexual; behaving like a stereotypical man but as a woman; being demonstrably angry. In other words, it’s just another way of calling a woman difficult and mystique-ruining. It seems to me that a subversive female protagonist is a catch-all phrase to describe someone who is—wait for it—human. As the comedian Jen Kirkman once said, “Women are literally human.”

Lucy is divorced and her daughter is in the primary custody of her ex-husband, which, despite everything I’ve said about subversive female protagonists and women being literally human, surprised me. In a good way. If you’re constantly inundated with a halcyonic image of motherhood—even if you are repulsed and have an immense ideological dissent with all of it—you are still being inundated. By which I mean, I am still pleasantly surprised when I come across a female protagonist who not only finds motherhood difficult, but actively seems to dislike it. Lucy could accurately be described as an anti-natalist. Mind you, that’s not the same thing as hating children, which, while increasing in social traction—I saw a bus ad recently suggesting that people limit themselves to one child for environmental reasons and no, the bus was not a relic from China—is still massively frowned upon, if no longer utterly taboo.

Lucy demolishes stereotypes about women, perhaps even giddily so (I should add that female characters that do, at least to some extent, fulfill stereotypes about women, have a lot to offer. After all, a stereotype is a massive oversimplification; it is the very opposite of nuance). Lucy becomes a dog owner, which had this effect on her:

Acquiring a dog changed me more profoundly than having a child did. Most people laugh when I mention this, as if I’m kidding, but some, new mothers in particular, visibly recoil. Gimli hollowed out a place in my heart and inserted a spigot out of which poured, if not exactly sticky affection for humankind, a new tolerance for people and their foibles that I had hitherto lacked. (p. 122).

Of other mothers, Lucy expresses that “The other women frightened me with their zeal for educational paraphernalia and their deep knowledge about the toxicity levels of various teething apparatuses” (p. 125).

If books like Regretting Motherhood: A Study by Orna Donath, Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty by Jacqueline Rose, Motherhood, Sheila Heti’s autofiction novel, and The Push by Ashley Audrain are anything to go by, motherhood is difficult. It’s not a secret, either. So why is the myth of maternal bliss or even maternal instinct still floating around like irrepressible lint, causing detritus that, even when confronted with the truth, seems inordinately difficult to eliminate? Perhaps women themselves are complicit in helping to propel the easily disproved fallacy that motherhood is not only life-changing (of course it is), but the quickest shortcut for a woman’s life to have meaning, selflessness, and exultance? I mean, of course women are complicit in helping to support the myth. The myth has been around for so long that it would be strange if they were not. Of course, this myth is a real disservice. The state of not having a child becomes an identity and is treated like a dearth, i.e., childless (hence why some people prefer to say “child-free”). But, as Heti points out, why is the negative constitutive of an identity?

In Heti’s autofiction novel, the protagonist expresses ostensible ambivalence about motherhood. After running into a friend with all the conventional markers of success, i.e., a husband and children who learns that Heti doesn’t know if she wants a child or not, Heti’s friend says: “You should go and spend some time with people who do have children, watch them and see what it’s like. I thought, I don’t even want to spend one second doing that” (p. 132). That doesn’t sound like ambivalence to me, but actual distaste for a lifestyle dictated by motherhood.

Meanwhile, Lucy is flummoxed when her daughter, Pippa, stares forlornly at Lucy’s fridge, devoid of Pippa’s artwork. There is no pretence at a maternal instinct:

“What had upset her? I didn’t know much about children—not anything really, except that I’d been one once—but this didn’t seem normal. The fridge was bare, not even graced with a grocery list or a souvenir magnet. Was she disturbed by her own reflection?

“Her drawings,” Julian leaned in and whispered. He indicated my fridge with a nod of his Colin-Firth-as-Mr.-Darcy chin. He whispered for me to fetch them. “Just tell her you were cleaning for our visit and put them away for safekeeping.” He put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Lucy, please.”

But, of course, I really couldn’t. And I couldn’t admit I had thrown them out. In a strangled voice, no longer sotto voce, Julian told me not to be a cunt and stick some bloody drawings on the bloody fridge so we could go have our bloody dinner” (p. 73).

Lucy has “long believed that people ought to have licenses for having children. It’s more difficult, more dangerous, and there’s more potential for wholesale destruction than with driving or flying a plane. The shocking negligence with which we procreate!” (p. 78). To which I say: indeed.

Near the end, we learn of Lucy’s relationship with Oisín, a “wee man” in Ireland, who was “frightfully charismatic about his passionate devotion to his cause and the fact that he didn’t give a fuck what anyone thought of him” (p. 223). Lucy speaks about her abortion without censure, though she does say “I’m resolutely pro-choice, but there’s a degree of brainwashing that occurs when you’re marinated in Catholicism in your formative years, when you embrace the faith with an adolescent fervour as I did. I’m preprogrammed to think of a fetus as a person. So not murder in the first degree, but manslaughter, if you will. My plea: self-defence” (p. 224). Her strongest surge of affection for Oisín? “I never adored Oisín more than the afternoon when I told him I was going to dispose of his child as if it were a carton of Chinese takeout gone off. I needed to appear that offhand if I wasn’t to cave. Did I subconsciously want to cave?” (p. 222). Oisín couldn’t be more different from Pippa’s father, Julian, the British lawyer she eventually marries and divorces.

Although the Anthropocene havoc—my own coinage for what is usually referred to as climate change (a comprehensive but also suffocatingly broad, bland term) and, anachronistically still, global warming—is not a major focal point in The Beguiling, when Lucy is, essentially, being monologued by a panoply of plants in the Waterlily Pavilion, the human role in ecological destruction is clear. The plants have a lot on their minds:

Our bitterness extends well beyond the missing pleasures of procreation. We know our Shakespeare. We identify with Shylock. Does a milkweed not bleed? … That bitter discharge from what you call euphorbia that stings and burns your clumsy fingers? Think of that as silent weeping. The sweet-scented mounds of cedar and pine on the sawmill floors? Call it teardust. Far from insensate, we feel much too deeply. …

We want—nay, demand—our pound of flesh.

… And who among your kind has considered the loneliness of office plants, cowering under artificial light, cigarette butts and the dregs of weak coffee polluting their meagre soil? When our liberation begins, the ficus and philodendron will be on the front lines.

… We will smother you as you sleep, pull you earthward as you trudge loudly through glen and vale on your determined eco-vacations, poison you as you nibble at your little al fresco feasts, strangle you as you continue to thumb yourselves into catatonic states, as you sweep the filthy laneways of your cities, as you chant to your one god, or many gods or loudly deny the existence of any deities. … Enough with the Greek and Latin! Enough with the yoke of Linnaean binomial nomenclature! We want to name our own names, we want to explode taxonomies, criss-cross borders. It’s true that we respond well to music. But it is time to make our own music. Sing, O Muse, of the rage of that fool Achilles all you want, the raging of your gods and your inchoate boys and your abandoned girls. We are our own muse and we will drown out the bleatings of the human sheep (pp. 247-250).

Gartner is able to distill humour from cancer:

Alopecia. There’s another fine word, speaking of inevitability. When you had radiation treatment, the hair on your head was the first to go. In solidarity with your scalp, you got a full Brazilian. Your husband tried to hide his delight, but not very well. “Is having cancer always this sexy?!” Then he looked mortified and cradled your bald head as if it were a dead kitten, a weird dead Russian hairless Sphynx, and wept (p. 91).

The long-running idea that female characters need to be both likeable and relatable—whatever the hell that means—is a bullshit expectation with a strong foundation in expectations of women at large. People like flaws; they like antiheroes. Whether they like antiheroines as much is another thing altogether, but even these leniencies come with biases of what constitutes an endearing flaw and what is unforgivably objectionable. I adored Lucy precisely because of how self-aware, shame-filled, and clever she is, how grippingly unmaternal and dog-loving she is. Lucy doesn’t need to be likeable, but she is. She’s exhilaratingly antithetical to conventional lies we’ve been fed about motherhood, but nevertheless steeped with a guilty conscience for myriad perceived sins.

Zany, smart, and adroitly droll, The Beguiling’s most beguiling aspect is how one person—Zsuzsi Gartner—has the gall to be so singularly talented. Gartner has a maddening amount of talent, with not a drop wasted. One can only hope to absorb some of it through osmosis.

*

Jessica Poon is a writer, line cook, and pianist in Vancouver. She recently completed her bachelor’s degree in English literature at the University of British Columbia. Visit her website here. Editor’s note: Jessica Poon has also reviewed books by Robyn Harding, Brad Hill & Chris Dagenais, Lindsay Wong, Emily St. John Mandel, Sheung-King, Eve Lazarus, Annabel Lyon, Monika Hibbs, Grant Hayter-Menzies, and Wayson Choy for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster