1012 Behold the Broughton Archipelago

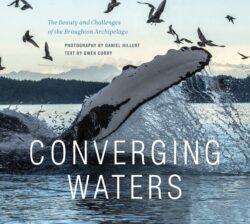

Converging Waters: The Beauty and Challenges of the Broughton Archipelago

by Daniel Hillert (photos) and Gwen Curry (text)

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2020

$40.00 / 9781771601658

Reviewed by Alex Zimmerman

*

There’s something attractive about archipelagos. They are, by definition, surrounded by water and therefore have no hard boundaries. Nonetheless, islands grouped into an archipelago have a distinct identity and character that draws us to them.

There’s something attractive about archipelagos. They are, by definition, surrounded by water and therefore have no hard boundaries. Nonetheless, islands grouped into an archipelago have a distinct identity and character that draws us to them.

For millennia, boaters travelling the Inside Passage who wished to reach the Broughton Archipelago of islands, between the northeast coast of Vancouver Island and the British Columbia mainland, have had two choices; from the north or the south. From the south they must run the gauntlet of the turbulent tidal passes to the south, either Seymour Narrows in Johnstone Strait or the chain of the Rapids in the tangle of islands and channels to the east: the Yucultas, Greene Point, and Whirlpool. From the north they must brave the unpredictable weather of the open coast of Queen Charlotte Sound to get around Cape Caution and then into the somewhat more sheltered waters that lead to the Broughtons. Either route made the Broughtons difficult to get to, especially if you were in dugout canoes or small, unpowered, or low-powered boats. Prior to European contact and settlement, this geographical position gave the Kwakwaka’wakw people, whose ancestral home this is, some measure of protection from raids by other First Nations on the coast.

These barriers did not stop settlers from establishing fisheries and forestry operations that once, for a few brief decades, occupied every sheltered inlet and cove along the coast. So numerous were they that Betty Carey, in 1937 at the age of 22, was able to row her shockingly small dugout canoe solo from Anacortes in Washington state to Alaska, without carrying weeks or months of provisions, relying on the hospitality of the logging and fishing camps and canneries along the way. Those populous days are long gone, along with the canneries, camps, and hand-logger’s floats.

Now, the region’s natural barriers once more act as filters, straining out at least ninety percent of the horde of recreational boaters that swarm the waters further south in the Salish Sea. Recreational traffic from the north consists largely of boats that have gone north and are returning on their way south. There is commercial traffic, of course, but most of it passes through the area and does not linger, with the exception of fish boats in the right season. There is now road access to the Vancouver Island side of the archipelago, but despite the influx of tourists and sport fishers in the summer, the area remains sparsely peopled.

The result of this confluence of geography with past and present human activity is an area unique to the coast. The population is not large and the ways to make a living few. The boater or kayaker (and really, this is the only way to experience the Broughtons, in my view) will encounter islands that seem largely untouched, wildlife in an abundance not found further south, and they will certainly not be bored by the changeable weather. In any given week, even in the summer, you are liable to experience everything from a tranquil flat calm to a full-blown gale, with periods of fog and rain thrown in to round out the scene. Even one brief trip in the archipelago leaves an indelible impression on those of us coming from outside. Those of us who have visited there by boat are usually drawn back again and again by the beauty, the wildlife, and the spirit of the area.

All is not as it seems, however. As timeless as the archipelago appears to those of us who only visit, the area has changed a lot over the past couple of centuries and is under threat of even more change in the near future.

This new book of photographs and prose from Daniel Hillert and Gwen Curry, Converging Waters: The Beauty and Challenges of the Broughton Archipelago, new from Rocky Mountain Books, focuses attention on the area and the challenges it faces. This is a handsome 8½ x 9½ hardcover book with full colour, full-page photographs (and one map) on thick glossy paper. Most of the 125 photos are by Daniel Hillert, with a few by Jackie Hildering, Eiko Jones, and Jared Towers. The accompanying text by Gwen Curry consists of four chapters: Community, Forest, Whales, and Salmon, with an introduction, another section at the front that is a kind of preface or second introduction, and finally a conclusion at the back.

What have Hillert and Curry set out to achieve with this book? They state their intention in the Introduction: “Dan wanted his third book to tell stories of the local history and its people, and of the challenges that this pristine-looking archipelago is facing.”

How well is this intention realized?

The photographs are wonderful. They illustrate and document, with an archivist’s accuracy, many instantly recognisable places where I have been and whose moods I have experienced. For those that haven’t visited, the photographs will be tremendously evocative of the temperament of the archipelago in all its moods. There are photos of the landscape and seascapes, and of the animals and the fish that inhabit or pass through the waters. There are photos of the built environment, sparse as it is, and photos of boats of all kinds, from simple skiff to cruise ships. And there are wonderful images of weather — the mercurial, dramatic weather of the archipelago that is central to the character of the place.

There is not a lot of text, about 34 pages in all, including the introductions and conclusion. The text does not directly relate to the photographs. The chapter on Community starts, as it should, with the Kwakwaka’wakw people and their relationship to the land and waters, and they are treated very sympathetically in the chapter. The chapter then moves on to the more recent history of contact and settlement by outsiders and the boom-bust nature of the resource exploitation over the past century and a half. The Forest chapter starts with a brief history of forestry in the area before moving on to more recent times. The chapter on Whales jumps almost immediately into telling the story of the societal shift from regarding whales as just another animal to be harvested to the more recent understanding, based on research, that whales are intelligent creatures with complex social lives.

The last chapter, Salmon, is perhaps the most compelling of all. All five native species were the backbone of the First Nations food system due to their abundance and ubiquity. The interdependence of salmon and the health and vigour of the forests that nurture them has only been understood from a scientific perspective fairly recently. The chapter covers this and gives a brief nod to the history of the abundance of the fishery, the canneries, and the people. However, the bulk of the chapter is concerned with the loss and damage to salmon runs from over-fishing, forestry, and the arrival of open-net fish farms raising Atlantic salmon.

The text, then, does a good job of articulating the challenges faced by the archipelago. Yet the reader is left wanting more from the book. The authors say that they wanted to tell stories of the local history, but I feel that they have given somewhat short shrift to some of that history. The first two chapters, together, are only a little more than half the length of the last two chapters. The treatment of Indigenous culture and experience is somewhat cursory and simplistic, focused mainly on the impact of outside explorers and settlers. Pre-contact Indigenous history is much more rich and nuanced than that.

An example of the archipelago’s fascinating pre-contact history that could have been included is the fortified village of Mamillilakala. The village’s 6,000-year occupation, the siting, the constructed defensive features such as the cut-away high bank, and the placing of big rocks to disrupt incoming war canoes all illustrate not only of the ingenuity of the Kwakwaka’wakw but suggest that life was not completely idyllic before contact.

The Kwakwaka’wakw, along with many other coastal First Nations, had a stratified society with limited upward mobility in which they also practised slavery. The potlatch, in addition to being central to maintaining culture and traditions, was also very competitive. Warfare, as shown by the need for fortified villages, was always a threat. Yet none of this is covered.

I’d also like to hear more about the history of the forest and the forestry industry in the area, especially how the Kwakwaka’wakw used the trees, which were so much more than merely the source of “fibre” that they became to modern industry. More stories about the people who took part in the forestry industry would give a more human face to the background of the present unsustainable situation. Stories of Indigenous and twentieth century use of the forest would also serve to emphasize just how much has been lost.

I found the photo captioning to be rather odd and baffling. A few locations are identified, but most are not. Photos of wildlife are usually identified, but plants and trees are not. Perhaps the intention was that the images should speak for themselves; but if that is the case, why include any captions at all? I would have appreciated more commentary on the photos — where and why taken, what aspect of the history, people, beauty, and challenges they illustrate.

I see the lack of captioning as a missed opportunity for education and further elucidation of the intentions of the book. Photos of fish boats could be captioned to tell us what kind of fishery they are outfitted for, and what part specific fisheries play in the overall catch. Photos of trees and forest are a missed chance to explain how the big trees were cut by hand – a photo of a stump with springboard notches from the hand-logging era is a good example. A photo of a Humpback Whale breeching could have mentioned the incredibly loud cannon-shot noise that results when the whale lands on the water. These are just a few examples that occur to me; I am sure the photographer could tell a story with each photo.

These criticisms are, however, only by way of suggesting that this good book could have been even better. Converging Waters shows that the archipelago’s future decline is not inevitable; it is, as its closing line asserts, “a place worth fighting for.” Together, Daniel Hillert and Gwen Curry remind us that the archipelago remains, despite the changes that have taken place and the threats it faces, a place of incredible beauty. Their appreciative celebration of the people and nature of the Broughton Archipelago – Community, Forest, Whales, and Salmon — deserves a place on your bookshelf.

*

Before retiring, Alex Zimmerman consulted on operationalizing sustainability in the buildings industry, for both projects and organizations. Alex was the Founding President of the Canada Green Building Council (CaGBC) in 2003. CaGBC became, under his watch, a recognized leader on the national stage. For many years prior to that Alex honed his professional skills in public works organizations in BC and Alberta. He started his professional career as a maritime engineering officer in the Canadian Navy. Effective writing was critical to his success throughout his career. Alex has been an avid outdoorsman and sailor all his adult life. The Navy gave him a basic grounding in seamanship, navigation, and sailing. After that, he continued by teaching in the Canadian Power Squadron. He built all of his own boats; several kayaks and both of his sail and oar boats. He has put several thousand watery miles under the keels of his various boats, but he knows that the sea still has things to teach him. Editor’s note: Alex Zimmerman is the author of Becoming Coastal: 25 Years of Exploration and Discovery of the British Columbia Coast by Paddle, Oar and Sail (2020), reviewed by Brian Harvey in The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster