1008 Mighty land, small laws

The Diary of Dukesang Wong: A Voice from Gold Mountain

by Dukesang Wong, edited by David McIlwraith, translated by Wanda Joy Hoe

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2020

$18.95 / 9781772012583

Reviewed by May Q. Wong

*

Editor’s note: The West Coast Book Prize Society announced on April 8, 2021, that The Diary of Dukesang Wong: A Voice from Gold Mountain, by Dukesang Wong, edited by David McIlwraith, translated by Wanda Joy Hoe, has been shortlisted for the Roderick Haig-Brown Regional Prize in the 2021 BC and Yukon Book Prizes. Winners will be announced on Saturday, September 18th, 2021 — Richard Mackie

*

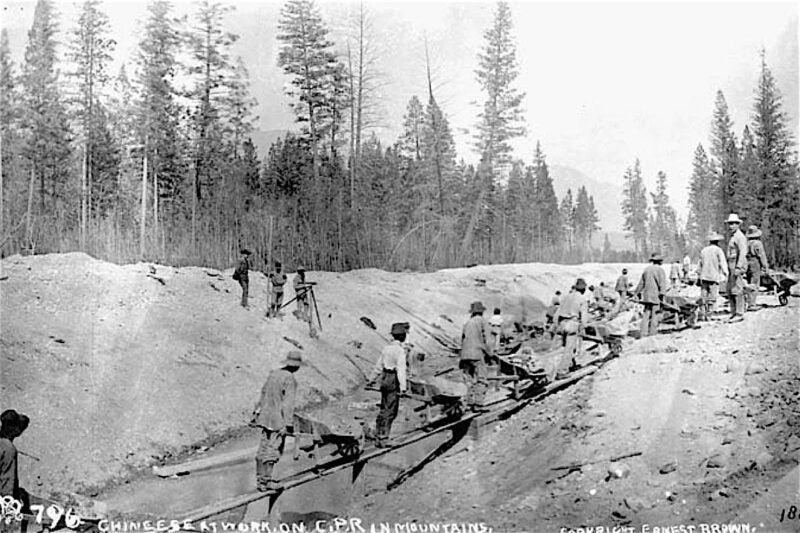

For almost 140 years, the voices of the thousands of Chinese who built the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) have been silent. While some faces may have been caught in sepia or black and white photos, they remain mostly nameless. Until now, when finally, a first person account written by Dukesang Wong (1845-1931) has become part of the written historic record of Canadian nation building.

For almost 140 years, the voices of the thousands of Chinese who built the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) have been silent. While some faces may have been caught in sepia or black and white photos, they remain mostly nameless. Until now, when finally, a first person account written by Dukesang Wong (1845-1931) has become part of the written historic record of Canadian nation building.

Original sources of information are the gold sought by students of history. First person historical written accounts of actual lived experiences are rare, and the further back in time, the lower the possibility that the journals of “ordinary” individuals have been kept, let alone cherished and/or shared publicly. Dukesang Wong’s diary excerpts are a treasure because they speak for the millions of early Chinese who escaped turmoil in China to find work and possibly a new life in Canada.

Editor David McIlwraith suggests other reasons for the dearth of such documents by the Chinese:

But pervasive myths tend to dissuade the searcher: the Chinese were illiterate, the Chinese didn’t keep diaries, their diaries could not have survived the decades, it was all destroyed in the Cultural Revolution, and so on.

A more accurate explanation for the perceived lack of primary sources might be that racism and violence directed at Chinese immigrants in the United States and Canada throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries included erasing them, both from the landscape and from history….The Chinese were attacked, killed, and driven out of towns up and down the continent. Their Chinatowns were torn down, burned down, and forgotten,….Their contributions were ignored and dismissed…. Is it any wonder that records and personal accounts are hard to find? (p. 6).

Wong’s writings are even more precious because these are the only surviving excerpts (covering the period 1867-1918) from his seven original handwritten notebooks that were all lost in a fire. The excerpts had been translated for this book by Dukesang Wong’s granddaughter, Wanda Joy Hoe, with help from two of his sons, Charlie and Dan. Wanda Joy Hoe had used the excerpts for a university assignment in 1966. Despite concerns about the limitations of these translated excerpts, such as the omission of personal family details, the story of how the paper from that assignment was re-discovered is also fascinating and is a testament to both fortune and persistence.

The totality of the excerpts comprise less than half of this slim volume, taking up only forty-nine pages, and printed in a larger font than that used for the accompanying informative commentary by David McIlwraith. Yet Dukesang Wong’s humanity shines through. The portrait I got from reading the excerpts is of a thoughtful, determined, hard-working family man. In addition to working on the railway, he was a scholar and teacher, a tailor, and a community leader.

Born in China, his family’s wealth and high social status allowed him to be raised in a life of privilege. He was given a superior classical Chinese education which enabled him to record his experiences and to ponder the circumstances of his life, work, relationships, philosophy, and social order. His status and education would have also led to continued personal advancement, but in 1867, a family tragedy reversed his fortunes and everything was stripped from him, including his parents, his family’s status, and even his ancestral home. It was this event which was the impetus for starting his diary. As the only son, he not only mourned, but for four decades thereafter wrote about trying to reinstate the family’s reputation in China.

His writings counter the stereotype of the Chinese railway labourer as illiterate peasants. As with immigrants from other parts of the world, the Chinese came for various reasons, from all walks of life and circumstances, and from different parts of China.

Wong’s traditional Confucian beliefs and values of embracing continuous learning, cultivating morality, compassion, and peace within oneself and in society, and loving one’s family are evident. While he admitted to not always being able to accept or adopt new ideas — “…I fear that I cannot change enough for this new world (p. 106)” — he sought opportunities for discussion with others on topics ranging from philosophy to politics.

For example, while still in China in 1879, he became acquainted with a Frenchman, likely a Catholic missionary, who spoke to him about Christianity. Although Wong was unable to accept the concepts of a personal saviour, an afterlife, celibacy, a virgin birth, or monogamy, he acknowledged (albeit somewhat guiltily), the value of the Western philosophy:

Today I may have dishonoured my great teacher in accepting another philosophy from a foreign land. Christian teachings are, however, just another point of view toward this life in which we all must exist, and it is certain, I think, that these lessons are about a good life of giving and helping other people. Knowledge must encompass all, including foreign teachings (p. 32).

He not only recorded the significant events in his life but also revealed his feelings. He wrote of his confusion and sorrow as a result of the family tragedy, of falling in love for the first time, and of wanting to break the bonds of tradition by showing consideration for his wife in public. Despite life’s challenges, he was also able to find things to be grateful for. For example, in the midst of worrying about the impact of the Chinese head tax on his countrymen, he wrote: “…I do wish the weight of the taxes on us was gone. One good event took place a few days ago, however, tea! Loads of tea for sipping” (p. 63).

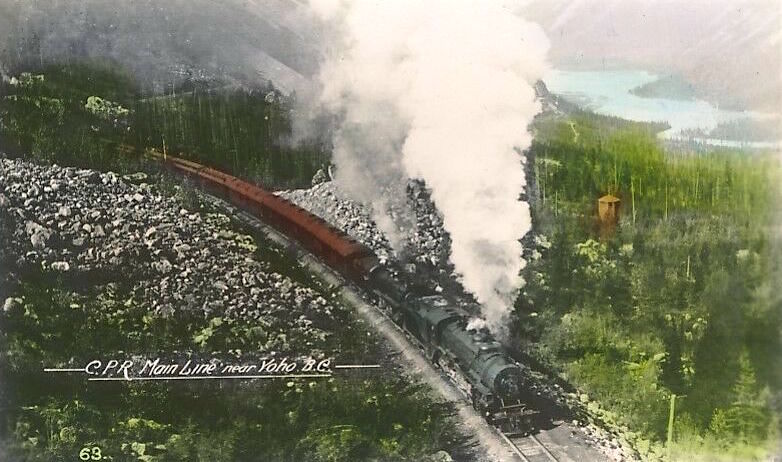

But most significantly he wrote about actually building the railway beds of this last and most difficult section of the CPR. It was this transportation link that was the carrot to entice British Columbia to join the Canadian Confederation. It was also hard, dangerous, and sometimes life threatening work for little compensation:

Autumn 1881 — The people working with me are good, strong men. There are many of us working here, but the laying of the railroad progresses very slowly. It seems we move two stones a day! And they want this railroad built across these high mountains, some two thousand miles! Even over the plains of our homeland, such railways took over a generation to build, so I can imagine these white people will face failed dreams (p. 57).

McIlwraith’s commentary provide context when dates, locations, and references to people were obscure. Using clues from the excerpts, he adds historical background to help the reader better understand what Wong was writing about. From the excerpt above, McIlwraith surmised that Wong was likely seeing the proposed route from the Fraser Canyon above Yale, where:

The number of tunnels to be dug through solid granite, and the cliff faces to be blasted away, and the hundreds of thousands of tons of rock that would have to be moved must have been daunting to the strongest of men (p. 70).

Wong was a labourer on the CPR, but he was also chosen by his countrymen as their spokesperson. His experiences served as a witness to the mistreatment, overt hatred, and institutionalized racism faced by the thousands who toiled on the railway. We hear Wong’s anguish at the illogical and inhumane treatment of his fellow Chinese workers and the pervasive and systemic racism they had to endure, for example:

Early autumn 1883 — My soul cries out…. Many of our people have been so very ill for such a long time, and there has been no medicine nor good food to give them. Even the strongest of us are weak without medicine to fight against these diseases, which spread very rapidly…. These are troubled times for us Chinese. There has been word among the employing company that we are not good workers and do not work enough for the schedules and plans of the railway owners. How does one work when so ill? (p. 59).

McIlwraith points out that Andrew Onderdonk, the American contractor responsible for constructing this section of the CPR, had seen the effectiveness of Chinese railway workers in the United States, and purposefully hired labourers from China for their skills and work ethic. Onderdonk knew they would ensure the delivery of a completed project on time – and also on budget, as the Chinese were paid only half the wages of white workers. Out of these wages, they had to buy their own tools, food, and whatever medicine they could find to treat injuries and illness. The lack of fresh vegetables and nutritious foods resulted in hundreds of Chinese workers dying of scurvy and other illnesses.

The money saved from Chinese wages was, of course, pocketed by the contractors as profits. White workers, on the other hand, were provided with gear, food, and medical care:

1885 — I am truly alone amid the dying. The leaders of the white people demand money — our poor savings — taken from we who have so little, given to those who are not so taxed (p. 60).

There is much work to be done and not enough people to labour at it. So many of us Chinese suffered and died recently; I cannot recall them all. But the western people will not allow us to land here any longer, while they scold us for not working enough. How these acts wear my soul down to nothing. Kwong tells us about the laws the white people have enacted to prohibit any further landing of our people. I cannot understand why. The work is great, and there aren’t enough labourers…. These mighty lands are great to gaze upon, but the laws made here are so small (p. 61).

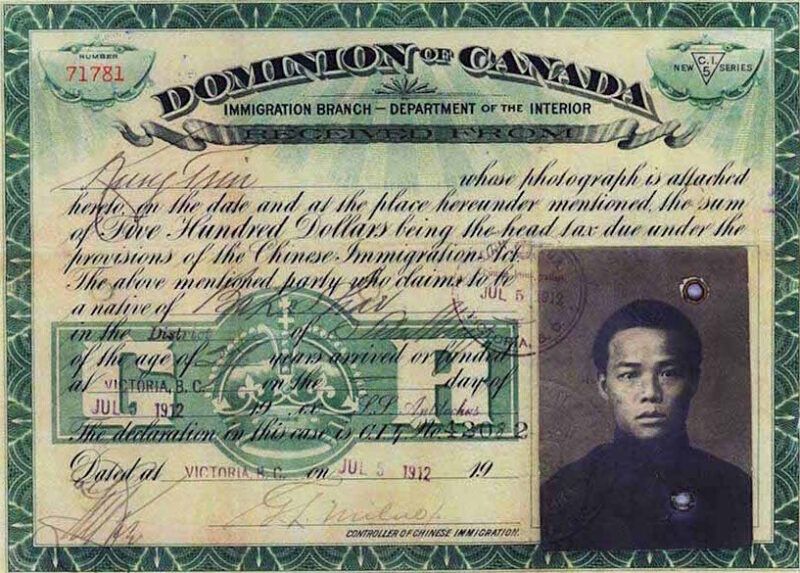

Wong refers here to the Chinese head tax. Even before the symbolic Last Spike was pounded into the ground on November 7, 1885, the Canadian government, prodded by the British Columbia government, passed a law on July 20 of that year imposing a $50 head tax on any Chinese wanting to come to Canada. The tax was imposed on Chinese people of any age, whether related to a Chinese already living in Canada or not. Amounting to about two months wages, the fee was intended to discourage further immigration from a people referred to by then Prime Minister John A. MacDonald as a “mongrel race” (p. 74).

In 1903, the tax was raised to $500, “or about $12,500 in today’s dollars” (p. 74). When that exorbitant amount was not enough to stop the Chinese fleeing war, revolution, and natural disasters to come to Canada, the Federal government passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which essentially barred all further Chinese immigration. Until it was repealed in 1947, only temporary residents like students and diplomats were allowed to land in Canada.

As the railway was being completed, the Chinese were no longer needed as a source of cheap labour, and already their contributions to this important work were being dismissed. The process of forgetting and disparaging the Chinese had been institutionalized. It has only been recently that federal, provincial, and even local governments have recognized and apologized for these past discriminatory actions.

Sometimes we might not think that these small personal surviving historical snippets are of lasting value or interest. On the contrary, it is through the lens and words of individuals like Dukesang Wong that history comes alive for future generations.

It is my hope that The Diary of Dukesang Wong: A Voice from Gold Mountain will uncover similar accounts from previously underrepresented communities, and ideally lead to their publication.

*

May Q. Wong researches and chronicles the extraordinary in ordinary people. She is a graduate of McGill University, holds a Masters in Public Administration from the University of Victoria, and retired from the BC Public Service in 2004. Her first book, A Cowherd in Paradise: From China to Canada (Brindle & Glass, 2012), concerns a Chinese couple separated for half of their 50 year marriage, and the impact of Canada’s discriminatory laws on their family. City in Colour: Rediscovered Stories of Victoria’s Multicultural Past (TouchWood, 2018) (reviewed by Tom Koppel) concerns the diverse range of immigrants and their contributions to Victoria. In addition to reading, writing, and speaking to groups about her books, May creates useful and beautiful things with knitting and sewing needles – the latest being hand-beaded face masks. Editor’s note: May Wong has also reviewed books by Henry Yu, Mei-Li Lee, Catherine Clement, and John Price with Ningping Yu for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “1008 Mighty land, small laws”