#963 If I came back as a flower

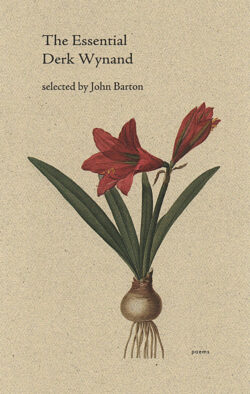

The Essential Derk Wynand

by Derk Wynand, selected by John Barton

Erin, Ontario: The Porcupine’s Quill, 2020

$14.95 / 9780889844407

Reviewed by Christopher Levenson

*

To be direct, simple, and yet also powerful in the evoking of strong, intimate emotion is one of the trickiest tasks for any mature poet but Wynand succeeds impressively, even in such early poems as “What I remember:”

To be direct, simple, and yet also powerful in the evoking of strong, intimate emotion is one of the trickiest tasks for any mature poet but Wynand succeeds impressively, even in such early poems as “What I remember:”

Of/ the women who/ held the ladles / I remember only/ the salt in/ their voices. Of/ my teachers I / remember best of/ all you. reminding / me nightly of/ the words for / night —

To this ability he often adds a sly charm, as evidenced in the prose poem “One cook, once dreaming,” or in the effectively whimsical and affectionate “A kind of Spring Fever,” which starts: “if i came back as a flower would you pick me if i spoke/ says eva my wife.”

Indeed at times Wynand seems to take an almost flirtatious delight in his own insouciant versatility. Take these lines that conclude “Tropical Snowman:”

Yes of course it’s self-referential — or is it

reflexive? — the cozy vacuum of our lives

promising to keep us warm as coffee or soup

and me, presumably snow or ice before, now melting

toward you, and you, without pretence to modesty

claiming those classic lines you have given yourself.

And while you don’t return my gaze, neither do you

refuse it. No, this work catches us well enough,

you with your dreams of steamier climates,

me with mine of chasing after you south.

So too in “Crosswords,” where his wife Eva’s search for clues, Sibelius’ music, medications, and the intrusive sound of nearby church bells establish the context for a domestic relationship that is wittily outlined in the final lines:

Churches, he says,

should haul down their bells, give it a rest.

A silence, she says, in music, four letters, thank you.

His travel poems, whether set in Cuba, Mexico, Portugal or the Netherlands, share a similar lightness of touch in their evocations of local atmospheres. Typically “Skating down a Dutch canal” (complete with its knowing references to modern Dutch writers) provokes him to imagine a whole life story for the young, blond woman skating behind him, while “Old Town,” set in Lisbon’s ancient Alfama district memorably captures an experience familiar to many travellers:

We accept the rain from the wash

overhead, the geraniums dripping

over the edge of a balcony.

Starting from the top we wind

left and right and left again

as the close walls dictate,

the only direction we can rely on: down.

However pleasing such poems of relationships and travel may be, Wynand’s themes are not confined, as Barton’s mainly biographical and not in any real sense critical introduction implies, to the intimately playful. Beyond the success of, say, “Earthquake,” which neatly combines dramatic presentation of the couple’s reaction to the physical event with an endearing intimacy, they extend also in a non-rhetorical way, to the socio-political in poems such as “Status of the beggar in Old Havana” or, more directly, in “Figure.” Here his typically measured and cool language, with its series of statements — in fact there are remarkably few questions in Wynand’s poetry — parallels the “professionalism” of the bureaucrats of genocide, such as Eichmann and Himmler, to achieve instead a bitter irony.

For me the lack of punctuation that is a notable feature in some of the middle and later poems is not a problem in itself. How could one not admire the illusion of ease in managing the sinuous syntax this necessitates, as here in the first lines of “Reconstruction”?

after such fires and counts of the dead no one foretells

that the smoke will clear that they will let go of their

claims and what claims them diamonds letting go of their

necks and fingers the titles forgetting the men who have

held them while bricks fall in on ancient deeds the hold

on things the hold of things broken like the portals and

doors the towers and city walls

Akin to an interior monologue, the constantly shifting focus of attention is almost hypnotic and, as befits a translator, Wynand shows himself to be acutely aware of the doubleness, the duplicity, of language. Nevertheless a technique that can sustain the reader’s interest for a page or so may be less effective over a longer term. Thus although no one would deny that “Airborne’s” eight pages without breaks and in one continuous sentence is a tour de force, for me at least, despite many attractive local effects, it was indigestibly long.

Although Wynand mostly avoids overt solemnity, and in poems such as “Chagall” can be positively delirious, it seems to me that his work flourishes and compels our interest by virtue of a directness of evocation, a tone of cool appraisal by his range of controlled suggestion and the simplicity of his diction.

*

Born in London, England, in 1934, Christopher Levenson came to Canada 1968 and taught English, Creative Writing, and Comparative Literature at Carleton University from 1968 to 1999. He has also lived and worked in the Netherlands, Germany, Russia, and India. He has written twelve books of poetry, the most recent of which is A Tattered Coat Upon a Stick (Quattro Books, 2017). He co-founded Arc magazine in 1978, was its editor for the first ten years, and was for five years Series Editor of the Harbinger imprint of Carleton University Press, which published exclusively first books of poetry. He has reviewed widely, mostly poetry and South Asian literature in English, in the UK and Canada. With his wife, Oonagh Berry, Christopher moved to Vancouver in 2007 where he helped re-start and run the Dead Poets Reading Series. Editor’s note: among the books he has reviewed for The Ormsby Review are those by Daniela Elza, Sarah de Leeuw, Susan Buis, Miranda Pearson, E.D. Blodgett, Nicholas Bradley, David Zieroth, and Kate Braid.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#963 If I came back as a flower”