#954 A counsellor’s perilous odyssey

Borderline Shine: A Memoir

by Connie Greshner, with a foreword by Theresa Therriault

Toronto: Dundurn, 2020

$19.99 / 9781459746121

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

*

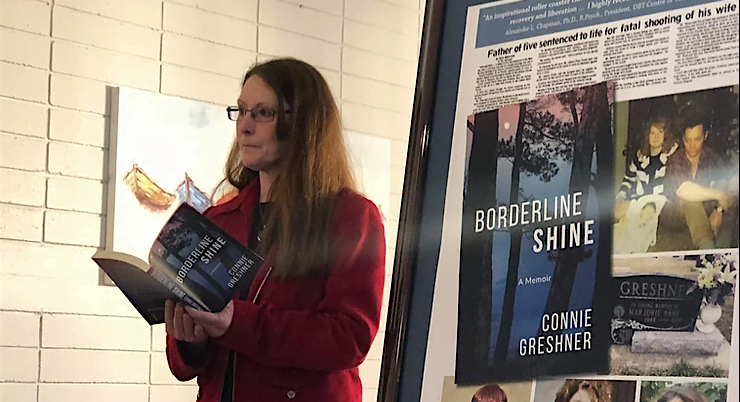

Connie Greshner calls her book a “memoir” but it doesn’t feel like a memoir. It feels like those painful slapstick comedies in which the protagonist suffers pratfall after pratfall, supposedly for our amusement, and may or may not skip bowlegged towards a happy conclusion. Only, Greshner is not narrating her pratfalls to make us laugh, and we don’t. By the end of this tumultuous, untidy, disturbing book, the reader is confused, battered, and wondering what to do next, much as Greshner has been wondering for most of her life. Then, as the credits roll on this black comedy, we glimpse a light and realise she is asking, even imploring, us to accompany her towards the light and help her keep it lit.

Connie Greshner calls her book a “memoir” but it doesn’t feel like a memoir. It feels like those painful slapstick comedies in which the protagonist suffers pratfall after pratfall, supposedly for our amusement, and may or may not skip bowlegged towards a happy conclusion. Only, Greshner is not narrating her pratfalls to make us laugh, and we don’t. By the end of this tumultuous, untidy, disturbing book, the reader is confused, battered, and wondering what to do next, much as Greshner has been wondering for most of her life. Then, as the credits roll on this black comedy, we glimpse a light and realise she is asking, even imploring, us to accompany her towards the light and help her keep it lit.

When she was eight years old, Greshner’s father shot and killed her mother. That is the first and overarching fact challenging the reader. The youngest of five children, Connie became “an awkward presence” amidst the chaos. No one, not the extended families nor the community (the small town of Ponoka, Alberta) nor the welfare and education systems, knew what to do with her, or with any of them: “we slipped through the cracks.” The father loomed over them like a malevolent shadow. A convicted murderer, he remained their legal guardian and took advantage of that position, trying to shame his children into achievement, estranging them from their mother’s family, and encouraging silence and forgetfulness. Connie’s comment cuts to the heart: “no one ever, ever mentions my mom.” Years later, out on parole, he told her: “Don’t you know what I did? I killed for you.” If there had been a separation rather than a murder, her mother would apply for custody, and he couldn’t let that happen.

As I read the Foreword by Greshner’s oldest sister Theresa, a mental health professional, I think back a very few years to when our small community suffered what seemed like a suicide epidemic. Somehow enough people went from feeling sorry and helpless to something I believe is called “empathy.” We were fortunate to have among us some people with the expertise and the will to push for aid in filling the gaps in our mental-health care, improving our links with the resources in the larger centre the other side of some bureaucratic barriers and bringing on site some professionals who cared.

The resources exist, but there have to be people who care enough to activate them. No one did that for Theresa and her little sister.

Connie Greshner’s illness has a name — Borderline Personality Disorder — which she did not learn until as a psychology student she studied the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, (DSM-IV).

She found it oddly comforting to recognize her symptoms: “How could they know what my life had been? What it still was?” That recognition had been a long time coming. Theresa assures us that Connie will “live her dream” and shine, but the beginning of the story is dark indeed.

Put in the “care” of an aunt and uncle, who had no place for her in their life, she was shuttled off to a Roman Catholic residential school in the American Midwest. Her experience differed from that of the children we these days associate most closely with residential schools, in that it was her own family and guardians who chose to put her there. She discovered censorship, rebellion, corporal punishment — and boys.

Back in Ponoka with her brother Steve and his wife Cathy, she continued her pattern as “a strange combination of overachieving nerd and crazy, dysregulated, trauma child.” Academically unstoppable, she achieved straight A’s through school and college, no matter how messy the other aspects of her life. The Greshners were written off by teachers, counsellors, law enforcement agencies, and neighbours as “one of the bad families,” beyond hope of saving, and left to survive as best they could.

Nor was this attitude unique to one community. Misunderstanding and rush to judgement were everywhere, and no sign of empathy. During her college years, seeking medical help, she overheard herself described as “another spoiled student whining that she’s depressed.” Her high school teachers assumed she would fail and did not bother to advise her which courses would be required for entrance to the University of British Columbia, her chosen place of study.

Early on she turned to alcohol. In Edmonton’s “scary bar scene” booze was her “saviour.” Drugs came and went — one is stunned by the casual references to “dropping acid — but for years alcohol was her major addiction.

And sex. Attractive, charismatic, exciting and aware of this, Connie nevertheless needed to prove her own worth and desirability, with an amoral disregard for whomever she might hurt. At age fifteen, she seduced a 22-year-old, “the most interesting thing that my adolescent eyes had seen in this sleepy little town.” A little later she considered herself “incapable of any healthy relationships,” yet a few times she came close to something meaningful, notably with three young men named (at least in this book) Jake, Jax and Jace. By the time she meets Jace, she is in her thirties and he is ten years younger, but it is with him that she forges a marriage, a family, and a working life. A lot happens before she nears anything like happy-ever-after.

Anything like a narrative summary eludes me. Connie Greshner gives new meaning to the concept of “no fixed address.” To and from Red Deer, sometimes alone, more often with one or more friends of either or both genders. Vancouver, Downtown Eastside, at the New Dodson Hotel, which now advertises as “a retirement home” but which in 1987 was an unsavoury unsanitary hole. Back to high school in Red Deer. A short time on the Sunshine Coast. An apartment in Surrey where “the tenants were all on welfare, some sold drugs, and the rest of us used.” Back to Edmonton’s “scary bar scene.” Several stints of employment at Alberta meat-packing plants, where she excels and advances — as she always does when she wants to. Physical fights with both men and women. Recurrent suicidal behaviour. Dogs and cats. Friends who disappear from her life and reappear years later, always under tentative circumstances.

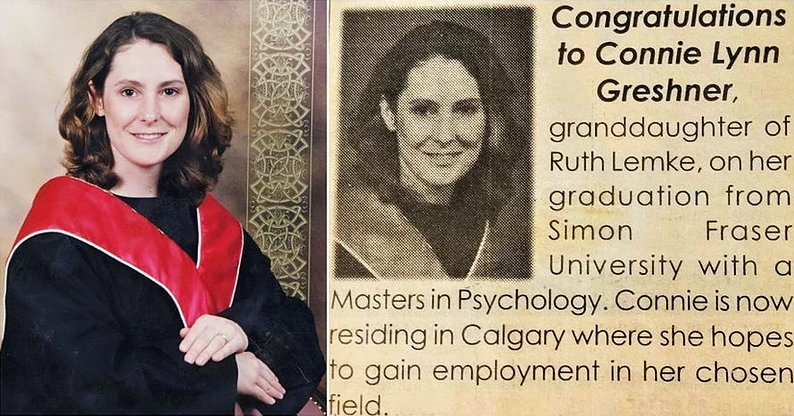

She kept on graduating “with great distinction” and went from Lethbridge to Simon Fraser University with a Research Council Scholarship of $16,000. She studied Neuropsychology and did a practicum at Riverview Hospital, where she realised that she could not merely diagnose a patient, but must do something: “assessment without intervention was not for me.” It was in this context that she recognised herself in the description of Borderline Personality Disorder.

Despite her achievements, Greshner continued dependent on alcohol and Speed. There were more “messy years” in Calgary and Red Deer, back in meat-packing, before we reach a chapter optimistically titled “Recovery.” She met Jace, with whom she works at “adulting.” For a while she was in Victoria, then back in Red Deer with her sister Theresa as life coach and a job as clinical psychology support worker, but still experiencing “cataclysmic shifts” and still drinking. Her vignettes of family life with Jace and their daughters are entertaining but a jaded reader may be forgiven some scepticism even after a physical collapse scares her enough to stop drinking.

Yet a change did happen. She began to like and trust herself, to “shine.” She, her family and her career moved to Vancouver Island, to a town which she calls “Greenwood.” The only Greenwood, BC, I can find is in the West Kootenays, but never mind — she is entitled to protect her privacy. Her account of her brother Steve’s death and her reconciliation with her siblings rings as authentic and true.

As we reach the epilogue and conclusion, we hear a loud and clear plea for help, for “someone to listen.” We have all encountered people who seem lost and beyond our help. Greshner provides some advice and resources for both the lost and those who would find them. But the message of this memoir/ manual is basically simple; do not assume, do not dismiss, do not judge. Do listen.

Whether or not the chosen format is the most effective for the message remains a question. More or less but not entirely chronological, the narrative is chaotic, confusing, even annoying. On the other hand, that is how things have been for Connie Greshner. Perhaps she did not need to include everything? but perhaps she did. Her own special gifts and intelligence make the chaos all the more compelling. She concludes: “My best hope for this book is to add to the growing awareness of the importance of understanding trauma and recovery. I hope that readers take away the message that judgment breeds shame and more suffering. Non-judgment breeds connection and healing.”

The book is a valuable insight into mental illness, and a reminder of human fragility. That Connie Greshner remains vulnerable is clear in her blog, where recent entries document events and feelings as the Pandemic closes in. What matters is that now she recognises the symptoms and knows how to deal with them. I wish her well, and I thank her for giving me the opportunity to listen to her story. Now, what can I do?

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications, including the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website. Editor’s note: for The Ormsby Review Phyllis Reeve has reviewed books by Ken Lum, Susan McCaslin and J.S. Porter, Ian Hampton, Robert Amos, Joe Rosenblatt, Eileen Curteis, Naomi Wakan, among others.

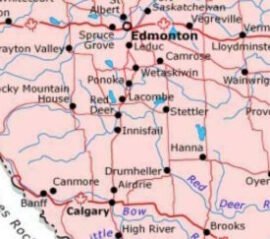

Phyllis Reeve adds a postscript about place. Connie Greshner’s birthplace and hometown throughout everything is Ponoka, a small town in south central Alberta. It is quite possible that I drove through it a long time ago en route to somewhere else. A year or so ago it turned up as the site of a mental hospital in Tina Biello’s Playing into Silence [Ormsby #559]. Before that, my reviewing of Dead Reckoning by Carys Cragg took me to Drumheller, Alberta, the site of the prison where Cragg met her father’s murderer [Ormsby 396]. I am glad I have personal ties to help me put the region in perspective. My husband was born in Stettler and spent his early childhood in Innisfail before moving to Calgary. We still have friends in Red Deer, the closest city to Ponoka, and the scene of much of this book’s action. I have cousins in Rocky Mountain House and happy memories of Drumheller. These are ordinary decent places, home to ordinary decent people, and that may be part of the point. Greshner’s frenetic dashes with all her worldly possessions as well as partners and pets back and forth between Alberta and the British Columbia coast might also remind us that these are close sister provinces, not so distant or alien. Just saying…

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster