#940 Mack the transcontinentalist

Riding the Continent

by Hamilton Mack Laing, edited by Trevor Marc Hughes, foreword by Richard Mackie

Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2019

$19.95 / 9781553805564

Reviewed by Steve Koerner

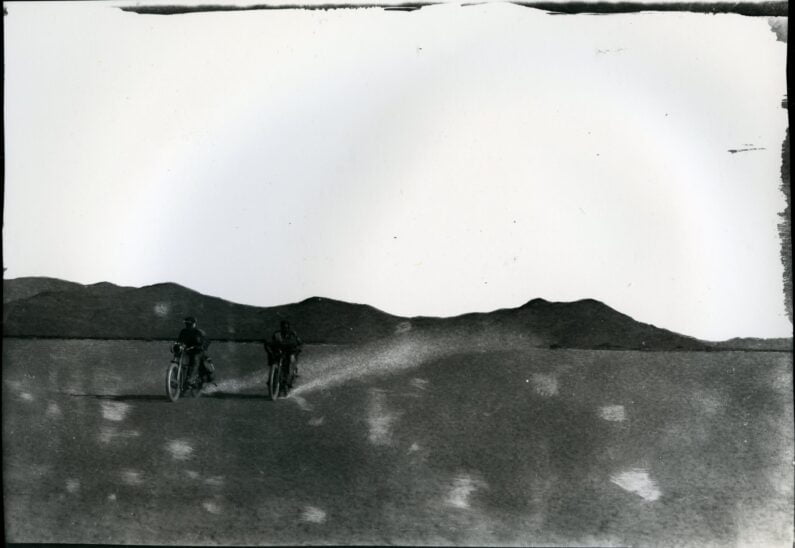

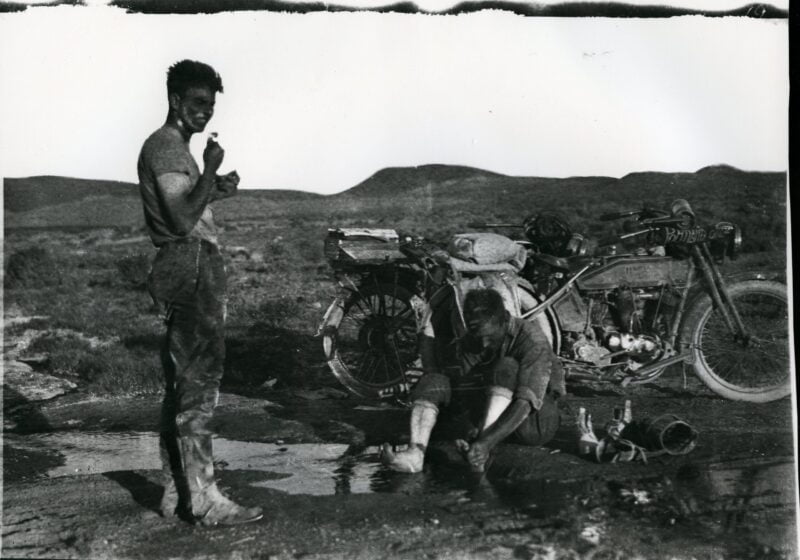

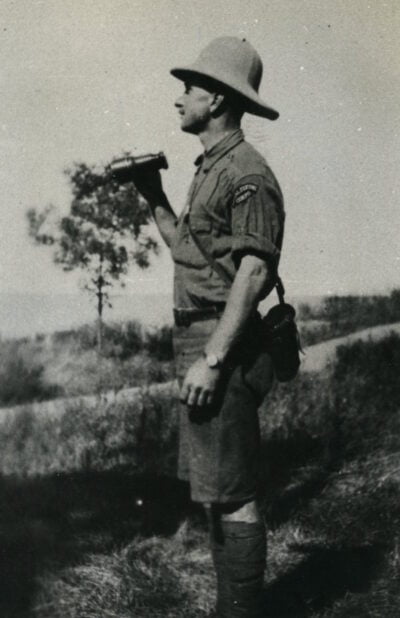

All B&W photos courtesy of H.M. Laing Collection, Comox Archives and Museum Society

*

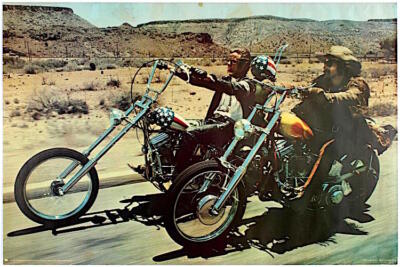

The hit 1969 movie Easy Rider featured two hippies, the self-styled “Captain America” and his sidekick Billy who, having just closed a highly lucrative drug deal, decide to ride their Harley-Davidson motorcycles eastwards from Los Angeles, intending to “find America” along the way. While doing so they experience a few adventures, smoke a good deal of pot and, when they reach New Orleans, drop some LSD and take in a bit of whoring as well.

The hit 1969 movie Easy Rider featured two hippies, the self-styled “Captain America” and his sidekick Billy who, having just closed a highly lucrative drug deal, decide to ride their Harley-Davidson motorcycles eastwards from Los Angeles, intending to “find America” along the way. While doing so they experience a few adventures, smoke a good deal of pot and, when they reach New Orleans, drop some LSD and take in a bit of whoring as well.

Alas, soon afterwards, somewhere east of the Mississippi River, their journey abruptly ended at the hands of a homicidal shotgun-wielding pig farmer.

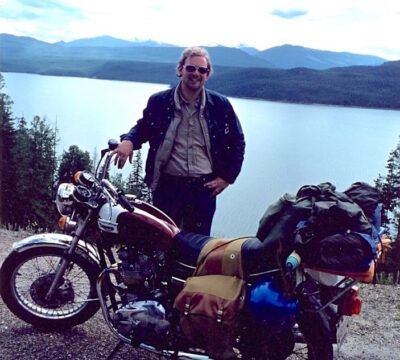

Riding a Harley-Davidson motorcycle is all Mack (Hamilton Mack) Laing would have had in common with that ill-fated cinematic duo. In Riding the Continent, his account of an epic motorcycle trip he took across the United States during the summer of 1915, there were no drugs, no whoring and certainly no death by shotgun (although Laing was sometimes harassed by unfriendly dogs and regularly tormented by clouds of voracious mosquitoes).

Instead, being an astute and sensitive observer, Laing has provided us with as much a detailed description of the lands travelled through, the people he happened to encounter and, most especially, of the flora and fauna seen, as he does about actually riding his motorcycle.

More than that, Laing also offers a fascinating snapshot of large parts of the United States during the second decade of the 20th century. Indeed, much of what we now take for granted in our 2020 automobile-centric world simply didn’t exist in 1915.

That was especially true of the roads, even inside some urban areas, which were then largely unpaved, sometimes amounting to, as Laing vividly relates, little more than winding dirt tracks.

Throughout the USA poor roads were commonplace and in Canada even more so. Indeed, as late as the mid-1950s, parts of the Trans-Canada Highway in the Prairies were still unpaved or otherwise incomplete and, until well into the 1960s, so too were sections of both the Yellowhead and John Hart highways in north-central British Columbia.[1]

Moreover, Laing’s journey took place at a time when North America was going through a critical transitional period in terms of public mobility. Mass production of the Ford Model T had commenced in 1908 and that would, within twenty years, enable millions of people to own their own automobile. However, in 1915 the majority of North Americans still continued to rely on railways, streetcars, bicycles or just walking as their means of regular transportation.

Indeed, as Laing observed on several occasions, out in the rural districts horse-drawn vehicles remained a common sight albeit were already being rapidly displaced by the internal combustion engine.

In 1915, motorcycles had kept an edge, although an increasingly precarious one, over automobiles in terms of price if not convenience. For example, a Harley-Davidson 11-F, like the one Laing rode, cost $275 while a Ford Model T car could sell for nearly $400. Consequently, motorcycles were still cheap enough to retain their popularity, despite various shortcomings, especially in cold or inclement weather never mind the rider’s far greater vulnerability in the event of a road accident, at least over the short term.

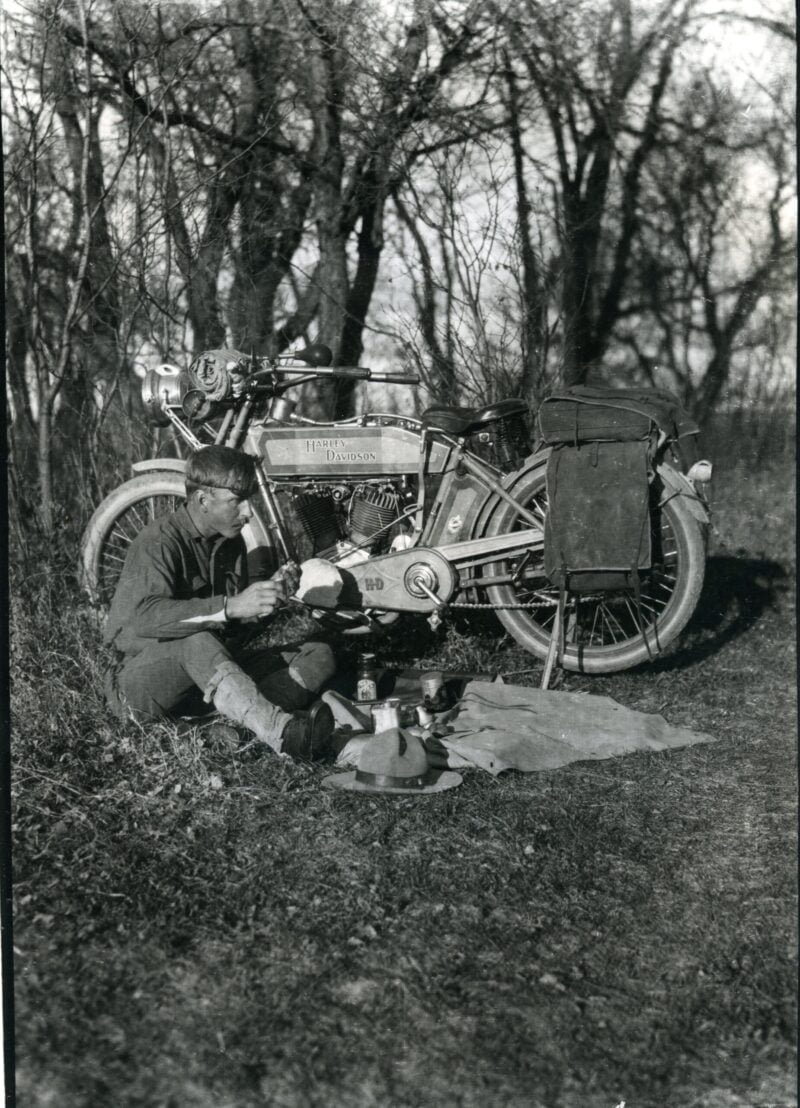

Laing tells us that he very deliberately picked a motorcycle to use instead of an automobile and not just for the lower costs. In fact, it was preferable to a mule too for that matter: “It is quite as tractable, covers the ground infinitely faster and there is perhaps as much poetry in one as in the other.” He used his to get out into more remote rural areas otherwise too difficult for other vehicles to access — indeed, Laing proudly called himself a “Motorcycle Naturalist.”

Consequently, riding a Harley across the continent that summer was not really an unlikely choice for him. Nor, even if his feat was hardly commonplace by the standards of the day, had he been the first to do so. In fact, the first recorded trans-continental motorcycle journey had already occurred in 1903 and, as recently as the previous year, Erwin “Cannon Ball” Baker had ridden an Indian motorcycle (Harley-Davidson’s main competitor) across the USA in only eleven days, an astonishingly short time considering the circumstances. Laing, by contrast, took just over six weeks but then he wasn’t in much of a hurry.

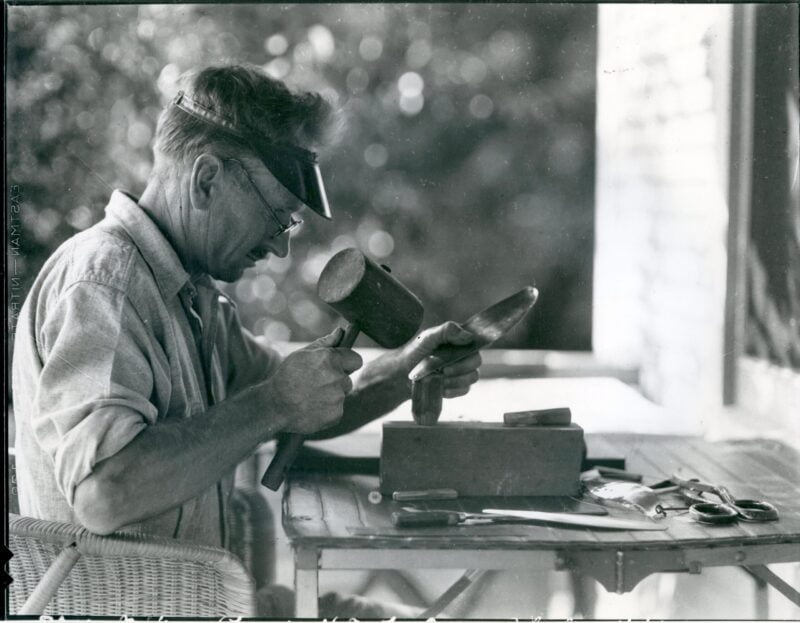

Born in Ontario in 1883 and raised from an infant in Manitoba, even as a boy Laing had shown a keen interest in the natural world, especially birds. He began his career as a rural schoolteacher but, at age twenty-eight, left for the USA to attend the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn New York. There he studied graphic arts as well as improved his already accomplished photographic skills.

He also pursued a successful career as a professional writer, having published his first book Out with the Birds in 1913 as well as articles that appeared in major American popular magazines such as Outing and Field and Stream often on topics involving natural history but also descriptions of other motorcycle trips he had made.[2]

So successful had he been as a writer that his fees helped support his motorcycling adventures and paid for the 988cc V-twin cylinder Harley-Davidson he used on this particular trip.

Laing left Brooklyn on 23 June 1915 riding his Harley-Davidson (or “Barking Betsy” as he called it) headed west following a sometimes convoluted route along a series of secondary and tertiary roads avoiding, whenever possible, the larger urban centres. If speed and convenience had been his top priority, he could have used the recently opened Lincoln Highway, one of North America’s first trans-continental routes.[3] Its two-lane surface was paved for the most part, however, Laing was far more interested in savouring the journey, pursuing what he termed a “gipsying expedition” and choose a very different route.

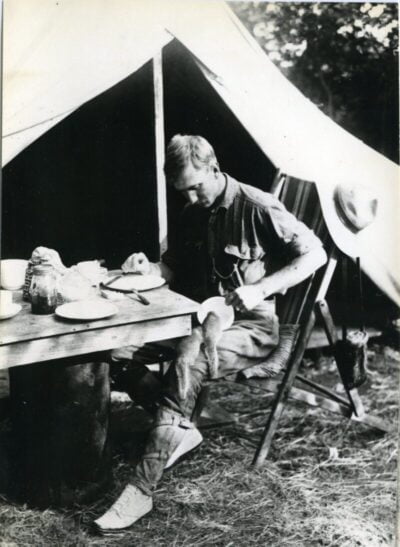

Back then there was a far narrower choice of accommodations, eateries and other conveniences available to him than to us today. Yes, he could find gasoline retailers, hotels and restaurants scattered around the countryside but certainly just a tiny fraction compared to the ubiquitous service stations, motels and fast food chain outlets one now sees clustered beside American Inter-State and other highways. Not that it made any difference to him.

Given the choice, Laing seems to have preferred dossing out in a farmer’s barn or, better yet, would simply stop and park his motorcycle a short distance off whatever road he happened to be following. There he would set up his canvas lean-to, cook dinner over a campfire, and sometimes listen to a coyote serenade before turning in.

The poor condition of the roads is a much remarked upon feature of his journey. So bad at times that he expressed distinct relief whenever he came across a section of the road that was actually paved or at least offered a firm dry surface. As a rule, however, travel could be and often was an ordeal. Once it began to rain, his motorcycle soon became stuck up to its hubs in thick mud or wet clay. He recounts one occasion while crossing Nebraska when his Harley was stuck so firmly in a deep mud-hole that it took a half-dozen labourers from a nearby road grading crew to help him manhandle it out.

Even when it wasn’t raining he could still find himself bogged down in mushy sections of the sand covered roads and, when his tires became mired in dirt ruts, the motorbike would repeatedly fall over, although not before throwing Laing over the handlebars.

Then he would have to struggle to get it upright again. Notwithstanding all these mishaps and despite the fact he didn’t wear a helmet nor any protective clothing, Laing seems to have suffered few if any significant physical injuries nor, for that matter, did the Harley ever become seriously damaged.

Still, the loose gravel or broken stone surfaced roads also meant flat tires were a regular occurrence. He could suffer several of them in succession during the course of a single day, each taking up to a couple of hours of tedious work to repair. That alone slowed him up considerably. Even keeping up a steady thirty mile an hour speed could be a major achievement. There were times when he failed to even keep that pace.

There were some mitigating factors. Then as now there was a strong bond between traveling motorcyclists. When encountering each other they would routinely wave back and forth and were always willing to help out if one of them had run into difficulties.

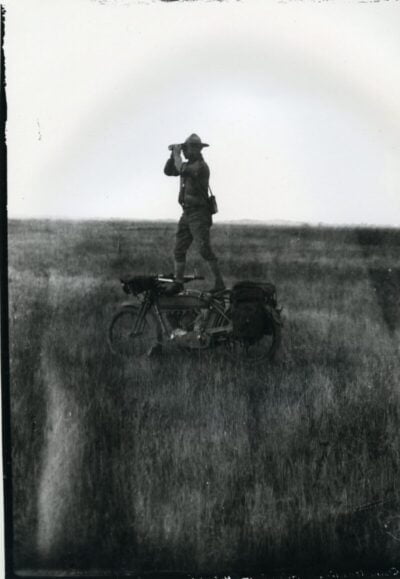

Help with road directions out in the more sparsely inhabited areas he traversed was especially welcome. Not only was there no GPS to guide the way but reliable maps were scarce. In some of the more lightly populated areas he passed through, signage was rare to non-existent and it was easy to lose one’s way.

Mechanical problems were also a preoccupation. However, the motorcycles of that early era used, by today’s standards, simple technology and Laing was often able to successfully perform roadside repair using the tool kit he had brought along with him. Still, he was always grateful for the assistance he received from the motorcycle dealerships who would regularly go out of their way to provide him with parts and service.

Keeping a slow pace had its advantages. He was far more closely in tune with his surroundings than a motorcyclist (never mind a motorist) would be today when traveling along an Interstate highway or other major route. He was a keen and close observer of the countryside he passed through, always on the lookout for local fauna not least the birds. In one instance, for example, while resting at the side of the road he noticed a meadowlark perched up in a nearby tree and eloquently described his delight when it broke into a “rich tremendous fluting” song.

After six weeks of near continuous travel, Laing’s ride finally ended on 8 August upon his arrival in San Francisco. Within a year Laing had prepared a manuscript about his experiences based on the travel journal he had faithfully kept while on the road. Unfortunately he was unable to find a publisher willing to take on the story of this two-wheeled odyssey across America. Perhaps his timing was a bit premature and too far ahead of public tastes because, only a few years later, the automotive travelogue literary genre, together with its motorcycle sub-genre, had already managed to firmly establish itself.

These accounts of travellers taking cars and motorcycles to both familiar but mostly exotic parts of the world, accompanied with colourful descriptions of obstacles encountered and overcome in the process, appealed to growing numbers of readers. Those seeking vicarious adventure could find it in books about motorised two-wheeled vehicle travel such as 20,000 Miles on a Motor Cycle in South India, Across America by Motor Cycle, Going Further, Roaring Dusk, and Nansen Passport: Round the World on a Motorcycle.[4]

After the Second World War the demand for further examples of this literary sub-genre continued into the 1950s and 1960s with books such as A Ride in the Sun, The World Before Us and others like them.[5] Their popularity carries on to the present day as titles like Jupiter’s Travels, Full Circle, Desert Travels, Bullet up the Grand Trunk Road and, probably the best known of them all, Robert Persig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Hollywood celebrity Ewan McGregor’s Long Way Round, prove.[6] Indeed, most reasonably well-stocked bookstores often have at least part of a shelf with motorcycle travel books available for aspiring two-wheeled adventurers.

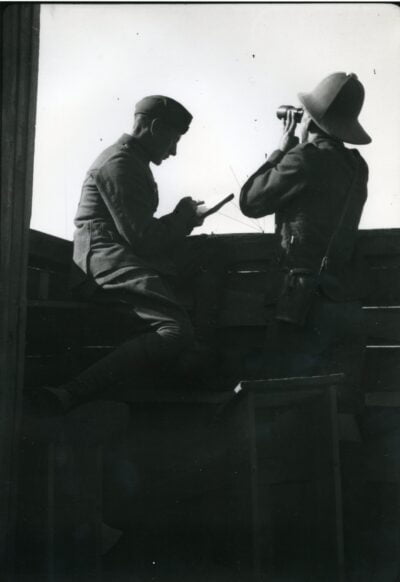

As for Laing, he joined the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 and became a gunnery instructor although he never actually left Canada on active service. During the 1920s and 1930s, he extensively travelled throughout western and northern Canada as a natural history specialist on behalf of institutions such as the Smithsonian, the American Museum of Natural History and the National Museum of Canada.

Laing continued to ride Harley-Davidsons for a few more years. Nonetheless, by the early 1920s he seemed to have abandoned motorised two-wheel travel for the remainder of his life. Laing married and settled down in the Comox Valley on Vancouver Island where he took up farming, continued to pursue his natural history interests and published articles in various magazines together with, towards the end of his life, another book.[7]

He died at age ninety-nine on 15 February 1982. Amongst his legacies is the Mack Laing Nature Park located near his old Comox Valley home.

Fortunately, the 1915 motorcycle journey manuscript was subsequently recovered by his biographer, Richard Mackie, who deposited it at the British Columbia Provincial Archives. From there it was later taken on by editor Trevor Marc Hughes and prepared for publication.

This book should give pleasure to more than just devotees of the motorcycle travelogue sub-genre and appeal to a far wider readership. Yes, in 1969 “Captain America” and Billy tried to cinematically “find” their America and failed. But, even though it has taken over one hundred years for Hamilton Mack Laing’s book to be published, there is no doubt he succeeded in finding his America and described doing so in a way that few others could have.

*

Steve Koerner, PhD, was educated at the University of Victoria and Warwick University, England. His book, The Strange Death of the British Motorcycle Industry (Swindon, UK: Crucible Books, 2012), won the British Archives Wadsworth Prize for best British business book. Steve Koerner lives in Victoria.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] See David W. Monaghan, Canada’s New Main Street (Ottawa: Canada Science and Technology Museum, 2002), pp. 72-75. See also Ben Bradley, British Columbia by the Road: Car Culture and the Making of a Modern Landscape (UBC Press, 2017).

[2] Hamilton Mack Laing, Out with the Birds (New York: Outing Publishing Company, 1913).

[3] The Lincoln Highway was officially opened in October 1913 and ran between New York City and San Francisco. It still exists although most of the original route has subsequently been absorbed by newer roads and Inter-State highways. See Michael Wallis and Michael Williamson, The Lincoln Highway: Coast to Coast from Times Square to the Golden Gate (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 2011), pp.1-7.

[4] See, amongst others, W.J. Hatch, 20,000 miles on a Motor Cycle in South India (1922), C.K. Shepherd, Across America by Motor Cycle (London: Arnold & Co., 1922), Eugene DeBogory, Roaring Dusk (Dallas, Texas: Kenilworth Publishing Co., 1928), Geoffrey Malins, Going Further (London: Elkin, Mathews & Marrot, 1931), and Ivan Sobolev, Nansen Passport: Round the World on a Motorcycle (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1936).

[5] See Peggy Thomas, A Ride in the Sun (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1954) and John Lennox Cook, The World Before Us (London: Quality Book Club, 1956).

[6] See Ted Simon, Jupiter’s Travels: Four Years Around the World on a Triumph (London: Penguin Books, 1979), Richard and Mopsa English, Full Circle. Around the World with a Motorcycle and Sidecar (Sparkford, UK: Haynes Publishing Group, 1989), Chris Scott, Desert Travels. Motor Bike Journeys in the Sahara and West Africa (London: Travellers’ Bookshop, 1996), Jonathan Gregson, Bullet up the Grand Trunk Road (London: Sinclair-Stevenson Random House, 1997) and Ewan McGregor (with Charley Boorman), Long Way Around. Chasing Shadows Across the World (London: Sphere, 2009). McGregor’s book was also adapted as the basis for a successful television series. Arguably Persig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1974) is as much philosophical rumination as it is a motorcycle travelogue. Other more recent examples of the motorcycle travelogue sub-genre include Paul Carter, Is That Bike Diesel Mate?: One Man, One Bike and the First Lap Around Australia on Used Cooking Oil (London: Nicholas Brealey, 2011), Emilio Scotto, The Longest Ride: My Ten Year 500,000 Mile Motorcycle Journey (Wisconsin USA: Motorbooks International, 2013) and Lois Pryce, Revolutionary Ride: On the Road in Search of the Real Iran (London: John Murray Press, 2018).

[7] The book is Allan Brooks: Artist-Naturalist (Victoria: British Columbia Provincial Museum, 1979).

7 comments on “#940 Mack the transcontinentalist”

Seriously, must read this!