#871 Memory’s lasting irritants

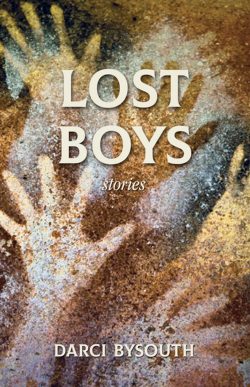

Lost Boys

by Darci Bysouth

Saskatoon: Thistledown Press, 2019

$20.00 / 9781771871754

Reviewed by William New

*

The most striking of the eighteen stories collected in Darci Bysouth’s first book read like those moments in our lives that we may want to forget about but never can. They keep coming back to irritate us — conversations we had or should have had, events that refuse to be suppressed, adventures in our histories that turn out to have been rash or dangerous or stupid or maybe even a reminder of what could have been when we finally chose convention instead. “The Heartbreaks,” for instance, tells of a group of teens who, high on weed most of the time, drive madly from Central BC to California in the 1970s in search of a musical high as well. What they see and what they fail to see lives on, though on return they’re soon seduced by what passes for suburban security or hardscrabble domesticity or random regret.

The most striking of the eighteen stories collected in Darci Bysouth’s first book read like those moments in our lives that we may want to forget about but never can. They keep coming back to irritate us — conversations we had or should have had, events that refuse to be suppressed, adventures in our histories that turn out to have been rash or dangerous or stupid or maybe even a reminder of what could have been when we finally chose convention instead. “The Heartbreaks,” for instance, tells of a group of teens who, high on weed most of the time, drive madly from Central BC to California in the 1970s in search of a musical high as well. What they see and what they fail to see lives on, though on return they’re soon seduced by what passes for suburban security or hardscrabble domesticity or random regret.

In other stories as well – “Petey” and “Lost Boys” for example — whatever is left behind keeps coming back to the narrator, demanding to be looked at. Hard fathers grow old and weak and confused; brothers with disabilities frame their sibling’s future; a sister is saved from death only to succumb years later to an overdose. Brothers, sisters, adolescent friends: the ones that get away can never get away, not entirely, but nor can she (or he) ever readily go back.

Sharp, but seldom funny, these stories are for the most part both humane and solemn. Settings range from Vancouver to the Scottish isles, from a university campus to lakesides in the Cariboo, from the 1970s to much more recent times. In “Cryptodrome,” Mt. St. Helens blows up, a metaphorical parallel to the main action. Writing about magma in her diary, one character in this story observes that crypto means hidden — the narrative exposes some of the secrets of sexual awakening and consequent questions of responsibility, the characters variously shown to be troubled and insecure. In another story, a man seeks the depths of a lake where he’s been told lie the bones of the past, but of course he cannot find them and nor can he solve his present dilemma. In yet another story, a woman seeks out her child’s father, only to find that he’s scarcely interested in the boy he did not know about.

The line between the imagined and the real is thin. In “Marrakech,” a girl and her mother live in a trailer park, on the bare earnings that come from what the mother weaves and sells, in the decade before tie-dying became fashionable; the mother keeps talking longingly about the vivid life in Marrakech that she remembers, and the girl suffers through the social slights of her biased and dismissive classmates. Years later, however, having survived adolescence, the girl learns that her mother’s Marrakech was more the fantasy of a wounded mind than a Middle Eastern reality; the story could have stopped here, but when the girl (now a mature adult) sets out to seek the real Marrakech because it seems to promise more fulfillment than whatever passes for ordinary life does, then the story moves on — but resists closure: it’s as though longing has been passed from one generation to the next, like a problematic gene of disaffection and desire.

Bysouth is most persuasive when writing about BC’s ranch country: its small towns, its one-industry opportunities, its tight-lipped families and rugged beauty. As represented here, stubbornness is a recurrent characteristic of the region’s parents and children; manliness is used as a term of both approval and threat; escape is constantly on the characters’ minds. In dark times, in these northern towns, mills close, violence flares, children disappear and families collapse. That’s Bysouth’s subject here: she does not pretend to solve problems, but she demands that attention be paid to them, and the act of story-telling itself is what drives the fragments of memory. The “Lake of Bones,” her narrator writes,

is something we all know. We know it if we’re Carrier or Chilcotin or some kind of white, if we’re reserve or ranch or if we got one of those fancy apartments in town. It’s part of being from here, like the sweathouse and the shot-up road signs and the pack of horses left to run wild down the stampede grounds…. The Lake of Bones is a terrible thing, terrible because of what’s underneath and hidden, but it’s a comfort too. It’s something that belongs to us.

And it belongs because it’s part of a story that’s shared — by old men on the salmon run, by “brush-cut white boys” at a Bible camp, by friends of the day, crouched around a circle with a joint. The “lost boys” of the title story may be dead, or may not be; reports of their disappearance may mislead; there may be any number of reasons why they’ve vanished. But the act of remembering is necessary, these stories say, no matter how much the memory irritates and the remembering hurts.

This is a first book of stories. There is much here that will engage any reader who is drawn to the human landscape of ranch country and to the fraught workings of memory, and many passages are enlivened by sharp detail. The stories themselves are sometimes a little long and a little rough: conversations can feel unworked and descriptive passages on occasion overwrought; several stories begin with a conventional ruse — a fragment of conversation that reads a little like a writing school’s motivational gesture: “Let’s go,” “Is he dead,” “You came” — but others are more formally adventurous, as in “The Things that Never Happen,” in which a set of clichéd assumptions turn out to hold hard truths. It’s when Bysouth probes these hard and hidden truths that her most arresting stories come alive.

*

William New is the author of Reading Mansfield & Metaphors of Form (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999); he has written widely on short fiction in Canada, Australasia, and elsewhere. He is also the author of a dozen collections of poetry, including The Rope-Maker’s Tale (Oolichan Books, 2009) and Neighbours (Oolichan, 2017). Editor’s note: William New has reviewed books by Julie Paul, Philip Huynh, and B.A. Thomas-Peter for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

3 comments on “#871 Memory’s lasting irritants”