#856 Alas, poor British Columbia

The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art

by Bruno David and Ian J. McNiven (editors)

Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019

$175.00 (U.S.) / 9780190607357

Reviewed by Chris Arnett

*

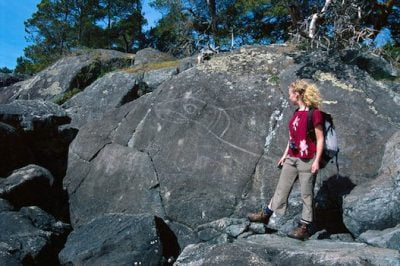

“Rock art,” for those who don’t know, is a general term for Indigenous paintings or carvings found on rock surfaces inside caves, on boulders, on cliffs, and on other geological substrates. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of these markings occur on every continent except Antarctica. In remote parts of Australia and perhaps elsewhere in the world, rock art is still being made and, on that vast continent as well as in parts of North and South America and Africa, rock art does not belong to a prehistoric past but is part of a living tradition. Wherever rock art is found it is the result of a specific activity which occurred at a specific place at a specific time, whether it was a charcoal drawing on the walls of Chauvet cave in France radiocarbon dated to 35,000 years ago or a red ochre painting on a Kingcome Inlet cliff commemorating a potlatch with — for the convenience of archaeologists and historians — the painted date of 1924. In other words, rock art has a history peculiar to where it is found and should not be confused with rock art found elsewhere. It may look similar, but rock art can be understood only in its local context. But that doesn’t stop people from making comparisons.

“Rock art,” for those who don’t know, is a general term for Indigenous paintings or carvings found on rock surfaces inside caves, on boulders, on cliffs, and on other geological substrates. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of these markings occur on every continent except Antarctica. In remote parts of Australia and perhaps elsewhere in the world, rock art is still being made and, on that vast continent as well as in parts of North and South America and Africa, rock art does not belong to a prehistoric past but is part of a living tradition. Wherever rock art is found it is the result of a specific activity which occurred at a specific place at a specific time, whether it was a charcoal drawing on the walls of Chauvet cave in France radiocarbon dated to 35,000 years ago or a red ochre painting on a Kingcome Inlet cliff commemorating a potlatch with — for the convenience of archaeologists and historians — the painted date of 1924. In other words, rock art has a history peculiar to where it is found and should not be confused with rock art found elsewhere. It may look similar, but rock art can be understood only in its local context. But that doesn’t stop people from making comparisons.

This tension between the local and the universal permeates the world of contemporary rock art research and partly explains why Indigenous British Columbia, which is rich in rock art and living rock art traditions, hardly figures in The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art, an otherwise magnificent 1135 page compendium on the state of rock art research worldwide edited by two leading rock art researchers, Bruno David and Ian McKiven, both of whom have worked with the custodians of Indigenous rock art sites in Australia. Forty-five chapters feature the work of 80 contributors covering diverse areas and subjects pertaining to rock art without much from an area of the world, British Columbia, with numerous sites and arguably the richest ethnographic data on rock art found anywhere in the world.

BC is not entirely omitted but relegated to a few very general paragraphs by David Whitley tucked inside an overview of North American rock art. In another chapter, with the rather ominous title, “Enigmatic images from a remote prehistory: rock art and ontology from a European perspective,” two European scholars question the veracity of an Nlaka’pamux elder, which is ironic given the title of their chapter and the subject of ontology, or ways of being. As I was involved in some of that original work I’ll have more to say about that below.

The lack of BC content in a book on world rock art is not surprising given two things: 1) a general ignorance by international scholars of BC rock art research, which is tied partly to 2) the agency of the rock art itself and its connection to a living tradition.

While there were early ethnographic inquiries into rock art in Australia, as attested frequently throughout this volume, scientific study of rock art actually began in British Columbia in the late 19th century with active collaborations between an Nlaka’pamux woman named Waxtko and James Teit, an anthropologist from Spence’s Bridge. Their collaborative work, published in the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History in 1896, was the first scientific study of a rock art site in North America. Teit went on to do more research, and, thanks to the cooperation and trust of his Indigenous teachers made available valuable information on rock art by informed individuals. Much of this work was published in academic journals and books but was little recognized in the world of rock art studies. Later 20th century BC researchers such as Doris Lundy, John Corner, Ed Meade, Beth Hill, and others built on Teit’s work by recording hundreds of sites along the coastline and interior travel corridors of the province and publishing books and articles on BC rock art. Interest culminated in 1977 with the British Columbia Provincial Museum hosting the fourth conference of the Canadian Rock Art Research Associates and the museum’s publication of CRARA ’77, a milestone academic work and the only compendium (so far) on Canadian rock art.

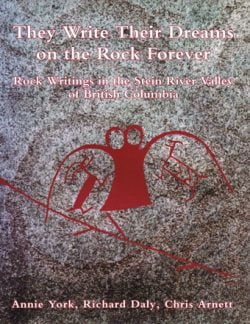

In the 1970s and 1980s, rock art sites became endangered and Indigenous people took initiatives to protect them. Rock art, or rather rock art sites, assumed a political role in the debate over land use, particularly in the Stein River Valley where a number of sites were endangered by the proposed construction of a logging access road. The presence of the rock art played a key role in the eventual preservation of the valley as a Provincial Park co-managed by the province and the Lytton First Nation. They Write Their Dreams on the Rock Forever: Rock Writings in the Stein River Valley of British Columbia (1993), co-authored by Nlaka’pamux elder Annie York, was written expressly to argue for the preservation of the valley by conveying its cultural importance as a place where Indigenous prophets left their paintings. Talonbooks has a new paperback edition in preparation.

In the 1970s and 1980s, rock art sites became endangered and Indigenous people took initiatives to protect them. Rock art, or rather rock art sites, assumed a political role in the debate over land use, particularly in the Stein River Valley where a number of sites were endangered by the proposed construction of a logging access road. The presence of the rock art played a key role in the eventual preservation of the valley as a Provincial Park co-managed by the province and the Lytton First Nation. They Write Their Dreams on the Rock Forever: Rock Writings in the Stein River Valley of British Columbia (1993), co-authored by Nlaka’pamux elder Annie York, was written expressly to argue for the preservation of the valley by conveying its cultural importance as a place where Indigenous prophets left their paintings. Talonbooks has a new paperback edition in preparation.

Annie York was a suywe, a plant specialist and seer fluent in several Indigenous dialects. She was also a natural historian who worked with many academics on various aspects of Nlaka’pamux culture, language, botany, and history. She was interviewed in her home on the late eighties and early nineties about drawings I had made of all the paintings at 17 rock art sites in the Stein River valley. The images were out of context but she was able to draw on the teachings she had received about the rock art in the valley to interpret the information. She placed it in the correct (emic) context, not one to be judged by outsiders but to be itself interpreted. This requires familiarity with local histories and of peoples and places. In her readings of the iconography, Annie York emphasized the role of the artists and the historic prophets (men and women) who predicted the coming of the whites. She used these intergenerational teachings as the basis for her interpretation of the rock art iconography in the Stein. The iconography conveyed the teachings of the prophets regarding origin stories and vision questing, things important to cultural survival.

No publications and only a few articles on BC rock art have appeared since then. Indigenous people are protective of the sites. Coffee table books on BC rock art may not be forthcoming. BC rock art, in the current local political climate of unresolved title and rights, is not always amenable to the kind of detailed scientific scrutiny and prolific publication of rock art imagery and sites in books and articles that occurs elsewhere on the planet. In 1999, for example, the Snuneymuxw First Nation of Vancouver Island successfully used the Trademark Act and a local education campaign to prevent the unauthorized use (on keychains, coffee mugs, t-shirts, etc.) of 10 important rock art images from their territory.

As images associated with holy sites, strict academic scrutiny of Indigenous BC rock art is not always desired or warranted. Detailed maps of these sacred sites and political entities are definitely not desirable: witness the 2003 boycott of a book on pictographs with GPS co-ordinates published by two BC Interior high school teachers which quickly drew the wrath and condemnation of Indigenous groups and archaeologists alike. Still, a lot of rock art research is being done today in BC in consultation with Indigenous people. Because it is part of a living tradition, research on rock art is generally circumspect and the results are not readily available or often shared. One of the few recent publications on BC rock art (on the Tseli-Waututh rock paintings of Indian Arm) by archaeologist Jesse Morin and myself appeared in the pages of Ethnohistory in January 2018 after more than two years of vetting through the community.

The content of The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art is dominated by the Australian context, where much of the cutting-edge rock art research on dating, recording, interpretation, collaboration, site management, and cultural appropriation occurs. In BC, Indigenous land claims brought together the mutual interest of archaeologists and Indigenous peoples and resulted in an explosion of research and documentation. Those few of us involved in this research in BC will appreciate the interesting similarities and differences, and, most excitingly, the possibilities of transposing method and theory (frameworks) to BC. Engaging chapters here such “The creolization in the investigation of rock art in the colonial era,” and “A new framework for interpreting contact rock art: reassessing the rock art at Nakara Springs, South Australia,” offer excellent case studies which may serve as models for rock art research in BC. Not all rock art is made by natives — and some “non-natives” shown in rock art may, in fact, be natives!

This massive volume is conveniently divided into four sections that focus on different aspects of rock art research, from the technical to the social. Part 1 features 12 chapters with up-to-date geographical and historical perspectives from around the world including areas previously ignored, such as Saharan North Africa, South Asia, and South East Asia, the latter chapter authored by Canadian Paul Taçon, a leading rock art researcher now working in Australia. Fellow Australian researcher Jo MacDonald, given the unenviable task of writing an overview for the Australian continent, no doubt echoed the concerns of the others when she writes that, “the volume of current rock art research makes writing a continent wide synthesis fraught with complexities.”

The rock art of British Columbia is only briefly covered in David Whitley’s chapter (with two paragraphs on the coast and three on the Interior) as part of a general survey of North America. Whitley knows California and Nevada well but is much less familiar with BC, a shortcoming that he has in common with other contributors. Nevertheless, the bibliographies that attach to Whitley’s and all the regional surveys — the one on the rock art of southern Africa is 14 pages long — are, along with the broad surveys themselves, invaluable guides to further inquiry.

Part 2 features the most challenging and sometimes frustrating section, with 19 chapters dealing with “Conceptual approaches to rock art: investigating meaning.” The problem with rock art is its universality, with all the implications that follow, the most significant of which is the distraction from the local. Apropos of this is the sole BC contributor, Thomas Heyd of the University of Victoria, whose chapter “Rock Art and Aesthetics” considers rock art’s universal attraction from the precarious standpoint of aesthetics, reminding us “that art is in context or it is nothing” (p. 79).

This gets to the heart of the matter in a critique of world rock art research. While there is a universal aspect of image making, there is little knowledge of the specific, i.e. the local, because in many places it is effectively gone with the passage of time or has been wiped out by colonial occupation. The perceived universality of rock art and the extreme lack of informed sources hamper all rock art research, especially in the realm of interpretation. This tension between the universal and the local, and trying to make sense of a practice spanning continents and time periods, tends to erase local history and essentialize what is a very diverse practice. The historical trajectories of every tradition should be clarified before any grand theorizing is attempted.

The chapter by Andrew Jones and Marta Diaz-Guardamino, “Enigmatic images from remote prehistory: rock art and ontology from a European perspective,” exemplifies the problems of reconciling universal aspects of rock art with the local. Boldly, the authors ask us to be cautious regarding the applicability of ethnographic knowledge, and assert that “the aim should not be to impose indigenous categories on bodies of rock art imagery. This kind of approach deadens understanding and produces course-grained knowledge of rock art traditions” (p. 490). This is a rather surprising statement given that so few rock art studies foreground any Indigenous content whatsoever (save for examples from BC). The authors instead argue for the primacy of formal quantitative methods, “whether rock art researchers are studying the parietal art of the European Paleolithic or San rock art in Africa” (p. 498).

Unfortunately, their otherwise engaging and methodologically sound argument of rock art as process suffers in its dismissal of one of the few culturally-authoritative narratives on Indigenous rock art, that of the aforementioned Nlaka’pamux elder Annie York of Spuzzum. Without going to the original publication, the authors cited an obscure article that presented Annie York’s narratives on rock art as problematic. For European scholars divorced from the cultural setting, this musing was sufficient reason to question York’s veracity on the subject. “In this case,” they write, “there was a distinct lack of congruence and of reliability relating to the interpretation of the pictographs compared against other forms of knowledge” (p. 483). Jones and Diaz-Guardamino present no evidence on which to make such a claim. Such an authoritative statement does indeed reflect European ontology after all, with its assumption of superiority over other ways of knowing or being. It is incumbent on researchers to study carefully the primary sources and not rely on secondary ones. Annie York’s name now appears in an international book on rock art — associated not with any cultural authority, but with error.

Part 3, Methods: Marks in Time and Place puts us on more solid ground with Guy Gibbon’s wonderfully succinct “The science of rock art research,” a user-friendly guide to the scientific method worth reading by anyone. His essay is followed by 11 chapters dealing with empirical and technical studies of rock art: recording, 3-D modelling of sites, pigment analysis, and various attempts to date rock art around the world using radiocarbon, optical, and uranium thorium dating.

The last part, The Public Consumption of Art: Applying and Managing Art in the Present, rounds out the book with six chapters on issues regarding cultural and intellectual property rights framed, as always, by local, political, cultural, and environmental settings. The appropriation of rock art imagery in Australia and elsewhere offers insightful (and sometimes amusing) examples. The book concludes with a moving chapter called “Visiting Gonjorings’ Cave,” co-authored with the official Indigenous custodians who describe in their own words the significance of a place people visit to construct “the map in our brain,” and to remind us of “how we are connected to country and to our relations to each other and to the painting itself” (p. 1099). For Indigenous people who maintain the connection, such sites are not dead and gone but here and now.

A must read for serious rock art enthusiasts, the size, content and price of The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art will prevent access to all but the most obsessed or interested. For those who make the effort, the world of rock art is revealed in all its complexity and cultural confusion. But as the editors explain in their introductory essay (available online for free, the rest is by subscription), the volume is only a step towards an archaeology and anthropology, implying, in good post-colonial fashion, that we’re not there yet. They understand that not everyone has the same research question, but as rock art researchers who have worked closely with Indigenous scholars, they reiterate that “the closer our investigations come to emic perspectives, the closer we come to understanding the ontological and epistemological position of rock art in the societies we aim to understand” (p.17). But as they also point out, in many places of the world this is no longer possible, and thus there are other dimensions to the study of rock art with other questions than those concerned with meaning.

*

Chris Arnett is an author, artist, archaeologist, musician, historian, and heritage consultant who lives on Salt Spring Island. He is an Honorary Research Associate in the Department at Anthropology at UBC and a sessional lecturer at both the University of Victoria and UBC. His parents, grandparents, and great grandparents instilled in him a keen interest in North American history and in the people and culture of his ancestral homelands of New Zealand, Cornwall, and Norway. He continues his ongoing self-directed and institutional ethnographic, archaeological, and sometimes musical research in British Columbia. With Annie York and Richard Daly, Chris wrote They Write their Dreams on the Rock Forever: Rock Writings in the Stein River Valley of British Columbia (Talonbooks: 1993, new edition 2020). He also wrote The Terror of the Coast: Land Alienation and Colonial War on Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, 1849-1863 (Talonbooks: 1999), and he edited Beryl Cryer, Two Houses Half-Buried in Sand: Oral Traditions of the Hul’q’umi’num’ Coast Salish of Kuper Island and Vancouver Island (Talonbooks: 2008). For The Ormsby Review, he has reviewed books by George Manuel and Michael Posluns, Hans Winkler and Cease Wyss (T’uy’t’tanat), Diamond Jenness (Barnett Richling), Douglas Delaney and Serge Marc Durflinger, and Genevieve von Petzinger.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

6 comments on “#856 Alas, poor British Columbia”

The trouble with “rock art” studies is that they are too focused on the physical, I suppose.

Chris Arnett’s excellent review of the Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art seems to overlook, both in his review and whether the topic is touched on in the book, the subject of the term “rock art” itself. As early as 1995, Mark Dudzik in an article on “The Rock Art of Minnesota” states that the phrase is a misnomer; “indeed in many quarters this application has been discarded in favor of terms such as ‘rock graphics,’ ‘rock painting,’ etc.” The word art conjures a Eurocentric view of how Indigenous peoples conceptualized their work. The still unknown function and meaning of so-called rock art including petroglyphs, pictographs, and petroforms suggests the need for a more appropriate term such as iconography. Alas, rock art may be too hard to erase from our (colonial) vocabulary. Rock iconography, though, has a neutral and more universal connotation.

Agreed. That’s why I spelled it “rock art” with quotations. In my scholarly work i use the indigenous terms.

Great review! It is really surprising how even in 2020 an academic handbook by specialists inadvertently perpetuates broad cultural assumptions that blind us from the cultural complexity of the world about us. It always makes me wonder what the point of literacy is if it does not invite us to doubt our own assumptions and learn to listen?

Of course, as a citizen/ settler of Gabriola Island, I feel the petroglyphs which we are privileged to know about deserve a mention in any such study. A good starting point is the Gabriola Museum, especially the journal Shale: https://gabriolamuseum.org/connections-and-resources/shale-publication/

I can think of a number of other fascinating BC sites. Probably there’s a book for Chris Arnett to write, bringing the research and stories together.

I’m on it.