#807 North Pacific Imperial Gothic

The Birdcages: British Columbia’s First Legislative Buildings, 1859-1957

by Robert Ratcliffe Taylor

Victoria: FriesenPress, 2020

$16.99 / 9781525547041

Reviewed by Martin Segger

*

This handsome, generously illustrated volume is essentially the biography of a building. Building biographies, multi-disciplinary by nature and ranging across the architectural, social , and cultural historical genres, are all too rare — perhaps because they so often cross the boundaries of historical specialties as they are taught. But Robert Ratcliffe Taylor has obviously found a niche here. It is his second such book; the previous volume, The Spencer Mansion: A House, a Home, and an Art Gallery, applied some kind investigation into the history of the former Rockland family home (1912), now the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. However, unlike the Spencer Mansion, of the Birdcages not a trace remains today.

This handsome, generously illustrated volume is essentially the biography of a building. Building biographies, multi-disciplinary by nature and ranging across the architectural, social , and cultural historical genres, are all too rare — perhaps because they so often cross the boundaries of historical specialties as they are taught. But Robert Ratcliffe Taylor has obviously found a niche here. It is his second such book; the previous volume, The Spencer Mansion: A House, a Home, and an Art Gallery, applied some kind investigation into the history of the former Rockland family home (1912), now the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. However, unlike the Spencer Mansion, of the Birdcages not a trace remains today.

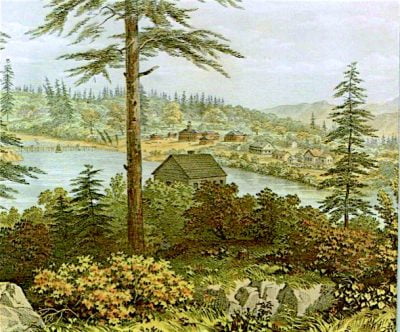

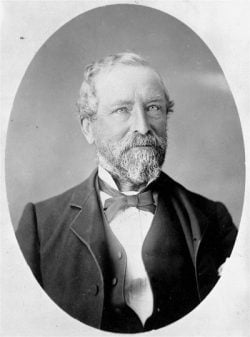

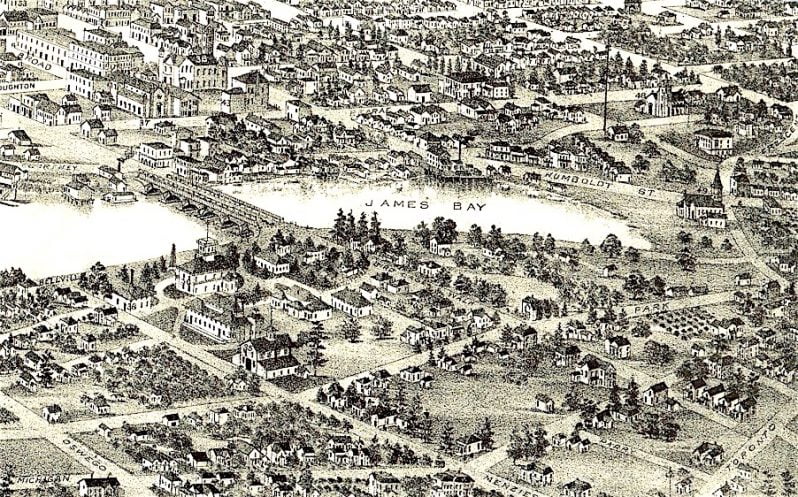

Termination of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) occupation licence in 1849, prompting the formation of the Colony of Vancouver Island, was followed in 1858 by the sudden arrival of over 30,000 miners seeking entry into the Fraser goldfields. The first of several “rushes” overwhelmed the local population of about 1000 residents huddling in the immediate vicinity of the HBC’s Fort Victoria palisades on the north side of the James Bay inlet. Over the next few years, side-stepping London Colonial Office opposition, former HBC chief-factor and now newly-minted Governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island, James Douglas, deftly organized a complex series of land-sale transactions to fund the construction of a set of administrative structures ranging along the south side of the bay. As Taylor points out, they effectively proclaimed a message of law and order to the waves of disorderly migrants suffering all the symptoms of the gold-fever delirium on the door-steps of this out-of-way colonial outpost. Douglas intended it to demonstrate the presence of authority; construction began in June of 1859.

Despite their diminutive scale when measured against the present neo-classical palace which replaced them 50 years later, in their day the Birdcages certainly claimed their own presence on the harbour front. Contemporary engraved illustrations present them as a piece of foreground stage scenery set against the high drama of the snow-capped range of the Olympic Mountains seen in the distance ramped across the skyline and rising above the littoral plains of the distant mainland, now Washington State, USA.

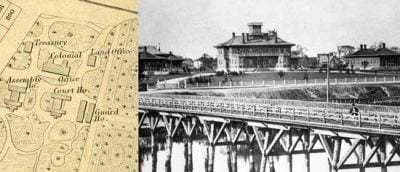

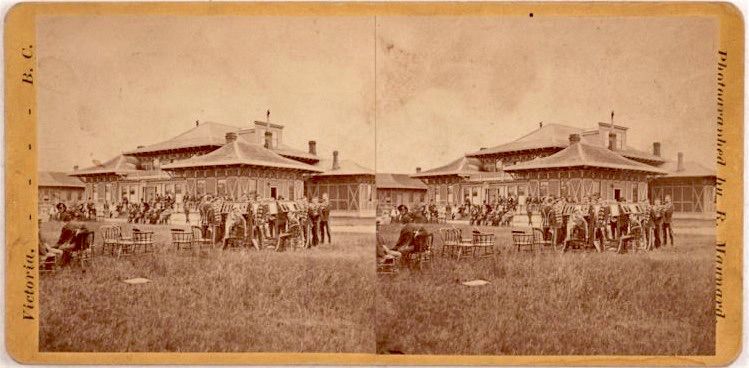

In ground plan, the main complex comprised five buildings set apart to mitigate the risks of fire. This included a pitched-roof central block anchored by a tower flanked by four one-storey cottage-bungalow structures. Further out on the periphery, almost as an afterthought, on the East side was a barracks for the militia, and to the West, as a later addition, the drill hall. The construction technology, unique in the day to Victoria, was timber with “brick noggin” infill, the exterior effect commonly known as “Tudor Revival” or “neo-Tudor.” Eves and soffits were articulated with decorative fretting and ornamental brackets. The centre building, the actual “colonial administration building,” first contained the governor’s office, and later (post-confederation) the office of the Provincial Secretary. Others variously accommodated the Hall of Assembly (or legislature), the Supreme Court, Treasury, and Land Office. Over time these functions were adjusted to accommodate the growth of the civil service and the functions of government.

They attracted public criticism almost from the outset as a “nondescript … gingerbread contrivances,” or by the Victoria Colonist newspaper editorial writer as a “mixed style of architecture, the latest fashion of Chinese pagoda, Swiss Cottage and Italian-villa birdcages.” And thus the name “Birdcages” stuck. The Colonist was under the editorial control of one Amor De Cosmos,” an ebullient Nova Scotian who, despite the suggestive eponymy of his assumed name, didn’t like much about the Colony’s Governor, James Douglas – or, obviously, his buildings.

Birdcages is very efficiently organized and highly readable. (Full disclosure: the author references several of my publications, and I reviewed early drafts of some of the chapters of this book.) An opening summary list of chapters includes references to the illustrations used. That, and the very complete index make this a very accessible text for quick consultations by others researching the topic. The fourteen chapters offer up bite-size chunks of the subject matter, beginning with one that quickly summarizes the social and political context of Governor James Douglas’s decision to commission the buildings. The next two outline the professional background and personal life of their designer, German-born Hermann Otto Tiedemann (featured in an essay by Robert Taylor in The Ormsby Review, no. 211, November 26, 2017 — Ed.). Taylor does a credible job of sorting fact from anecdote and fiction about this rather enigmatic figure. Frustratingly, as he admits himself, he was unable to fill a large lacuna in Tiedemann’s biography which has also eluded other historians of this period: that is, the missing details of his early training and life before he landed in Victoria to hang out his shingle as a land surveyor. Instead, Taylor does offer us some credible speculation.

The ensuing chapters, some quite brief, set the the buildings within the prevailing Victorian design aesthetic, cover the rather turbulent story of their construction, and describe the finished project in detail. Chapter 7 shifts the focus, first outlining a history of the use of the buildings, emphasizing the working conditions of several generations of civil servants, and then conveying through the eyes of the politicians how the legislative hall functioned, or not, including reference to the occasional public protest that sequestered the inmates for fear of serious manhandling if they stepped outside.

The subsequent topics Taylor recounts in fascinating detail include: how the building were a constant work-in-progress; issues arising from original design flaws or shoddy constructions; significant events including exhibitions of pomp and ceremony; and adapting one of the structures to temporarily accommodate the young one-way passengers arriving on the “bride ships” in the 1860s.

Taylor notes the ongoing and extensive repairs required to keep out the rain and drafts that constantly plagued all the buildings. He references comments, made at the time of construction, on the shortage of skilled trades and reliable contractors. Rightly so, although the specific problem was probably the construction technology which Tiedemann specified. The HBC had long perfected a technique for dealing with green timber which is subject to ongoing shrinkage over time. Their pièce sur pièce method of piling squared timbers into a slotted upright frame allowed for easy constant maintenance by just re-chinking the top horizontal timbers. Tiedemann either didn’t appreciate its utility in the changeable West Coast environment or he didn’t know about it. In the case of the Birdcages, the mix of stable brick with shrinking timber constituted what is called in heritage building conservation parlance “inherent vice.”

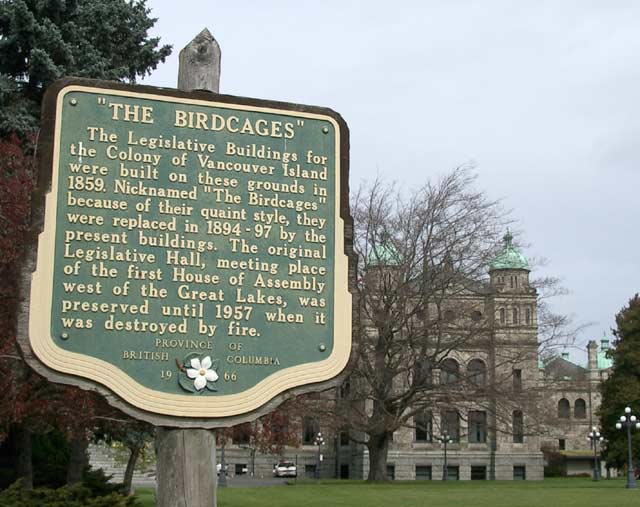

The final chapters of The Birdcages cover the rather ignominious fate of the complex as the site was re-arranged to accommodate the construction of the new “Parliament Buildings” in the 1890s, and the Birdcages’ final demise with the fire of 1957, which destroyed the last standing structure, the Assembly Building, long adapted to use as the Provincial Museum of Minerals. Oddly, as the author then notes, in an abrupt change of popular opinion, the buildings had become their own legend. A dewy-eyed nostalgia prompted many to remember them fondly, some even suggesting that the Assembly should be reconstructed in the province’s centennial year (1958) as a memorial to the province’s humble role in the great game of Britain’s empire on the Pacific. It was of course a futile wish, but an early indication of Victoria’s later enthusiasm for preserving its architectural heritage.

Dr. Taylor’s informal, even breezy, and highly readable writing style belies his significant academic credentials. However, these are certainly revealed in the back-matter, which is almost a volume unto itself. The eighty-some pages of appendices contain a list of significant structures in Victoria and New Westminster (the British Columbia mainland colonial capital) that were contemporaneous with the construction of Birdcages; a list of architects, contractors and tradesmen along with individual biographies associated with the buildings over time; an essay on the James Bay Bridge which connected the north and south sides of James Bay; another essay on Sir James Douglas’s own house, which by its use and adjacency to the Birdcages can almost be considered a part of the complex, and also a very revealing discussion on the trials and tribulations of actually carrying out the research and sorting through the often-times confusing documentation, or lack of it. The endnotes contain extensive footnotes, reference sources, bibliography, a very comprehensive index (tiresome to compile, but infinitely useful to other historians in the trenches of local history research — thank you!) and, oh yes, an autobiographic note which includes a very full list of the author’s previous publications!

In the opinion of this reviewer, admittedly an architectural historian, Taylor’s most significant contribution is to firmly locate the Birdcages within the Victorian romantic picturesque aesthetic, and thus the imperial ideologies of the day. He calls this the “colonial picturesque.” In doing so, demonstrating how this was done not only by clearly appreciating Tiedemann’s use of an eclectic stylistic vocabulary, but also demonstrating how the buildings were meant to be experienced. He devotes one chapter to a fictional visit to the building by a contemporary, a clever device which demonstrates how the buildings worked as ornaments within a contrived landscape garden park, or arboretum.

This idea died hard. Even though F.M. Rattenbury finally provided the province with a monumental Palladian villa to house the 1893 Parliament Buildings, he was careful to situate them within Tiedemann’s arboreal park. The editorial writer of the local Victoria Times newspaper began his review of Rattenbury’s new monument by imagining himself in a Wordsworthian sublime moment as a “South Sea Islander,” at some point in the distant future, ruminating on the ruined remains of this glorious pile, at what he describes as “the western extremity of Britain’s vanished empire.” Rattenbury was furious when the mature trees in front were cut down. The effect, of course, was to better show off this expensive new symbol of national hegemony that the brooding pile still commands over Victoria’s harbour entrance, an expression of the city’s ambition to be a major a communications and trading entrepot, equal to San Francisco, Tokyo, Calcutta, Sydney, or Shanghai.

The diminutive Birdcages make for an interesting architectural comment of the larger geo-political forces of the time. The elite rationalism of the enlightenment was giving way to the populist emotionalism underpinning the idea of the nation state. By the mid-nineteenth century Britain was feverishly constructing a new political ideology, ending the suzerainty of the early breed of multi-corporations (i.e. the royal charter monopolies such as the British East India Company in the Far East and the HBC in British North America) in favour of direct sovereign imperial rule. The 18th century Scientific Revolution was transformed into the 19th century Industrial Revolution, generating huge wealth for the new entrepreneurial class. The liberal Whig plutocracy of the Enlightenment had by marriage or purchase merged with the old Tory landed aristocracy. Holding the reins of power meant maintaining the loyalty of the mushrooming urbanized workforce of factory production, at home and abroad. To some degree unwittingly, John Ruskin and William Morris, both brilliant publicists, with their fantasies of reviving a glorious past imagined as a medieval peasant paradise, played into this.

Gothic provided a visual language for this. The contrived garden landscape, the promised Eden of medieval Christianity, provided a context. The change was so abrupt that in 1840 a Roman Catholic “gothicist,” A. W. N. Pugin, had to be brought in to shroud architect Charles Barry’s rationalist plan and classical elevations for Britain’s new parliament buildings in medieval wedding-cake finery. British cities and British colonies sprouted ornate gothic churches designed for ritual rather than preaching. Public gardens, contrived Edenesque landscapes, gave the image of Britishness to suburban England and also to a newly renovated colonial enterprise everywhere in reach of the Royal Navy.

Speculative housing tracts and country houses alike saw Palladian palaces replaced by overblown (or reduced) cottages, or sometimes even castles, set within garden landscapes. The classical orders of the old Empire, whether in the Caribbean, the South Pacific, or across the Indian Raj, gave way to the picturesque romantic piles of the new. Compare for instance the serious Georgian style Government House overlooking St. John’s built for the Colony of Newfoundland 30 years before the Birdcages. The India High Courts in Calcutta had to be Gothic, along with the railway stations. To avoid the tropical heat of the Indian Deccan, colonial officials retreated to their summer hill-station “residences.” At Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India, this was a Tudoresque country village clustered around an Elizabeth-style Royal Lodge and Gothic Revival Roman Catholic church, as well as a Viceregal Lodge (1880) in the Observatory Hills. At Ooty, featuring the Queen Victoria neo-gothic library and gothic-revival St. Stephen’s Church, the Maharajha of Mysore built himself Fernhills Palace (1844), essentially a range of Swiss chalet pavilions set in 50 acres of manicured gardens.

The Birdcages should therefore be cast in the role of garden pavilion architecture, set in a coniferous arboretum. Think of the eclectic assemblage of exotic follies dotting the landscape of Kew Gardens, well known at this time. Even so, like the Barry-Pugin British Parliament Buildings, the plan and layout of the Birdcages is a that of a classical Renaissance villa. This eighteenth century rational arrangement is then disguised in mid-Victorian romantic picturesque clothing. Amor De Cosmos, if as Whig-liberal as his name suggests, would probably have preferred a (republican) classical palace. He is quoted as once saying “what I love most … love of order, beauty, the world, the universe.” Understanding this explains the “completion” of the central administrative building with an offset conical tower. Taylor thinks it compromises the original design. It does, but it purposely corrects the too classical form of the original building to give it a more picturesque (and Canadian national?) silhouette — perhaps a subtle reference to the French Chateauesque style, the official variant of the “gothic,” an official branding exercise by the post-confederation Dominion of Canada.

Without doubt, consciously or otherwise, both Douglas and Tiedemann, along with the local colonial power brokers, evidently understood this. One of the first acts of Douglas when the HBC lands were ceded back to the Crown was to establish Beacon Hill Park. It, and Ross Bay Cemetery (1872) remain two of the finest examples of Victorian picturesque landscape design in Canada. Tiedemann’s reputation as an architect rests to large degree on his three gothic revival churches in Victoria and New Westminster. Victoria’s first Victorian garden suburb was laid out in 1865 by Colonial Surveyor-General Joseph Despard Pemberton, Tiedemann’s boss during the building of the Birdcages. (For this prestige-enclave of hobby-farm size residential country estates he subdivided part of James Douglas’ Fairfield Farm!). One is tempted to speculate as to whether or not Tiedemann had spent part of his “lost” years in the Pacific colonies.

Ideologies of architectural style track ideologies of governance and social order. The 19th century notion of the nation state was a heady mix of idealist sentiment, nationalist pride embedded in romantic historicism, and patriotic altruism. A utilitarian belief in science survived and, as the tumultuous debates in the Birdcages’ Assembly Building attest, so did a nascent notion of liberal democracy. But stripped down, it was an ideology of power writ large on an international stage. Colonialism, “the white man’s burden” and the notion of a superior “master race” were virulent strains imbedded within it.

Ultimately these presented as the Nazi and Fascist parties of Germany and Italy. It took two of the bloodiest wars in human history to kill off this particular virus, only to be replaced by two new equally grandiose political abstractions, Marxism (the Communist International) and global economic neo-liberalism. In the aftermath of WWII, these ideologies adopted their own signal imagery: Abstract Modernism, otherwise known in architecture as the International style. As its name suggests, it quickly became the symbol of both government and corporate institutions of the new global world order, from the Lever Bros’ or the Bronfmans’ corporate headquarters in New York to the gleaming banking towers of Shanghai and Kuala Lumpur; from United Nation headquarters in New York, to state-sponsored socialist neo-urbanism in Corbusier’s Chandighar, India, and Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasilia.

Perhaps we are currently witnessing the death-throes of these ideas as well, at the hands of an actual biological virus. If so, what architectural clothes will this new world-order adopt? Intimations of Immortality… indeed.

*

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of British Columbia, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (Heritage Architectural Guides, 1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on B.C. historic and decorative arts. His most recent publication, concerning the Modernist architectural heritage of Victoria (1935-1975), Conservation Guidelines for Modernist Architecture in the Victoria Region (2020), is available in a free on-line digital version. Martin currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia and for Government House, Victoria.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#807 North Pacific Imperial Gothic”