1267 Footman at Government House

ESSAY: An “Odd-Man” at Government House, Victoria

by Robert Ratcliffe Taylor

*

For most people, reading another person’s diary is a furtive and shameful act. For historians, however, studying the private journal of a long-dead person can be a valuable and exciting, if occasionally puzzling, endeavour.

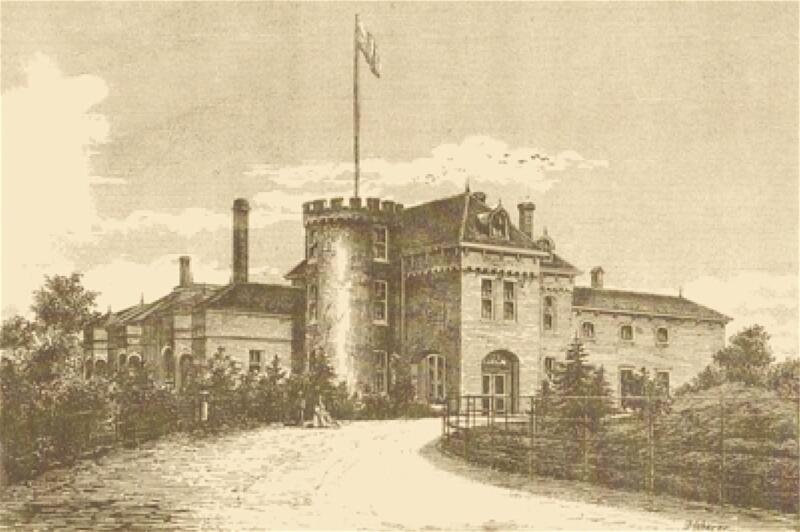

In 1870, Robert Colston was both the official government courier and a servant at Government House (“Cary Castle”) in Victoria, BC. While employed in these positions, he kept a diary which suggests that his daily life was complicated, even challenging.[1] His journal sheds some light not only on servant life in early Victoria but also on the role of the mansion in city’s economy and on the difficulties of maintaining the gubernatorial home at that time. Most important, the diary shows that Colston wore at least “two hats” and poses the question: why did he have so much work to do?

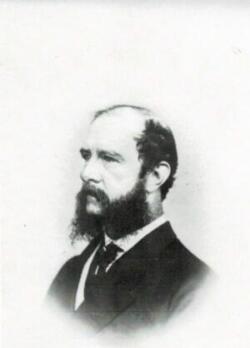

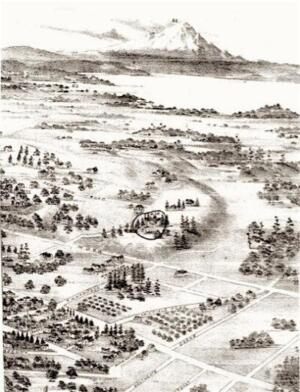

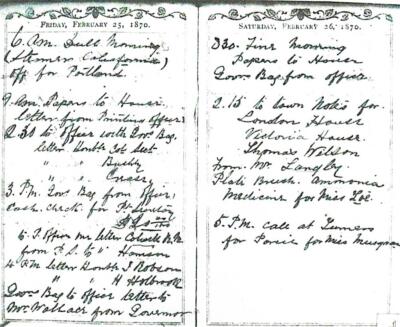

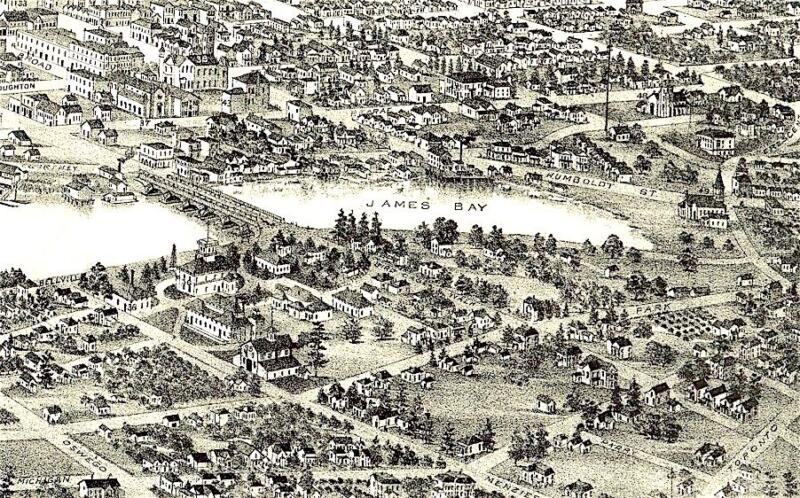

Colston’s official position was that of government messenger, taking documents and letters back and forth from the Legislative Buildings at James Bay in the city to Government House on Belcher Street (later Rockland Avenue), a distance of about three kilometres (1.86 miles). The available records suggest that he had worked for Governor Frederick Seymour in 1865-1869 before being employed by Governor Anthony Musgrave from 1869 to 1871. The diary is detailed from January to late July 1870 during which time particularly important government correspondence was carried by Colston between Government House and the Colonial Administration Building, the Legislative Council and possibly the Supreme Court and Treasury at James Bay (the “Birdcages”). Confined to Cary Castle in the winter and spring of 1870 because of a leg injury, Governor Musgrave had members of his Executive Council meet with him at the mansion to discuss BC’s joining Confederation while at the same time the Legislative Council debated the issue. Colston must have known that rain, snow and accident could damage the important documents with which he was entrusted, which may have been why he kept such a meticulous record.

After June 1870, the diary entries become sparser and gaps occur, possibly because less correspondence passed between the Castle and James Bay. By this time, the Legislative Council had voted to send a delegation to Ottawa with BC’s proposals and the governor, somewhat recovered from his injury, was more mobile and could meet with his Executive Council or bureaucrats in the Colonial Administration Building. Colston probably knew that the contents of his “government bag” were now less important and required less record-keeping. He continued to serve as messenger, however, until Musgrave resigned in July 1871, but no diary from these months has survived.

We have no birth or death dates for Colston but one Robert J. Colston arrived in New Westminster in October 1859 as a sapper and blacksmith in the Columbia Detachment of the Royal Engineers with whom he worked on the Yale -Spuzzum road, where he was injured in a rockslide. In New Westminster, he performed in the Royal Engineers’ Dramatic Club’s plays in the years 1861-1863. He must have had a sense of humour because, on March 21, 1863, in a farce presented by the engineers, “the appearance of R. Colston dressed as a ballet girl created perhaps more laughter than any thing else in the evening.”[2]

His wife, Frances Christie, was born in the West Indies, where Robert, who was with the Engineers there, met and married her. The couple had five children, Florence, Duncan, Sweeney, Robert and Elizabeth. After 1863, when the Royal Engineers were disbanded, his whereabouts and occupation are unknown but by 1865 he had entered government service, working on the gubernatorial steam yacht Leviathan which ferried Governor Seymour about on his official duties. Apparently in charge of the engine which powered the ship, he kept a journal between January 1 and June 13, 1865.[3] He must have followed Seymour to Victoria after the union of the two west coast colonies in 1866, serving as valet. The governor seems to have trusted his servant because the vice-regent’s private secretary records that, when on a ship to Bella Coola in 1869, Seymour fell ill and died “in Colston’s arms.”[4]

At this time, Robert and Frances had moved with their children to a private house in the James Bay area of Victoria. After Seymour’s death, Colston entered the service of the new vice-regent, Anthony Musgrave. Whether the new governor hired him as both a domestic servant and a courier is not clear. Government records note that, as a messenger, he was paid $500.00 per annum.[5] Presumably the governor also paid him for his domestic service but I have not found an account of this.

Colston may have been dissatisfied with his workload (courier and footman) at Government House because on March 9, 1870, while still employed by both Musgrave and the colonial government, he wrote from Victoria to Henry Maynard Ball, magistrate in New Westminster, requesting permission to take up his military land grant “for services rendered to the colony,” signing himself “late royal engineer.” Near the mouth of the Fraser River, he received 150 acres (60.7 hectares)[6] but he does not appear to have ever farmed this land.[7]

A government courier’s work was strenuous and demanding. The diary shows that, in all weather, Colston rode on his horse back and forth across Victoria, seven days a week, leaving early in the morning from the Legislative Buildings, riding up to Government House, presumably staying there until about 5 or 6 o’clock in the afternoon when he returned to “the Birdcages.”[8] With a leather pouch over his shoulder, and possibly with saddlebags, he was tasked with carrying important letters and memoranda not only to and from the seats of government but also to and from the post office, the telegraph office and the harbour. He often noted when ships arrived and if government mail was on board.

As a courier, Colston was important to Musgrave and to government officials and high-ranking civil servants and politicians. The governor had been mandated by the Imperial government to bring the united colony into the new Canadian Confederation. Insofar as Musgrave succeeded in his assignment, Colston played a small but vital part in BC’s becoming part of Canada in 1871. He notes that, in this crucial time, he carried the Governor’s letters to people such as Attorney-General Henry Crease, George Phillippo (who succeeded Crease), Philip James Hankin (former Temporary Administrator of BC), Joseph Trutch (Chief Commissioner of Lands and Works), and members of the Legislative Council such as John Helmcken, J.D. Pemberton and G.A. Walkem.

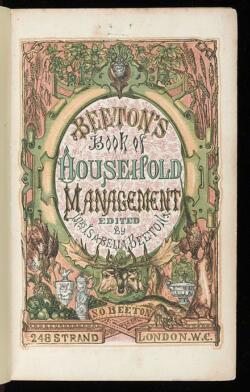

Although Colston is usually described as the “government” or “official” messenger,” he also functioned as a servant at Cary Castle, specifically as a footman but he could be called upon to execute miscellaneous duties. Colston was probably an “odd-man,” as defined by Mrs. Beeton in her Book of Household Management (1861):

Where a single footman, or odd man, is the only male servant, then, whatever, his ostensible position, he is required to make himself generally useful. He has to clean the knives and shoes, the furniture, the plate; answer the visitors who call, the drawing-room and parlour bells; and do all the errands. His life is no sinecure; and a methodical arrangement of his time will be necessary, in order to perform his many duties with any satisfaction to himself or his master.[9]

The “odd-man” was a jack-of-all-trades in the Castle where, as Mrs. Beeton noted, he was probably one of the few male servants. As a footman, Colston carried messages or letters from his master or mistress to friends, to the post office and to local businesses. He served meals and possibly admitted visitors — and served as Musgrave’s valet. In the latter role he would take care of the governor’s wardrobe, putting out the correct clothes for each day or occasion, and cleaning his boots, hats and shoes, duties which would engage him in the mornings and evenings at least — which raises the question of how Colston juggled the roles of both footman-as-valet and courier.

As Musgrave’s valet, Colston went to San Francisco on the occasion of the governor’s wedding to Jeannie Lucinda Field in June 1870. Shortly before the ceremony, he records lists, one including “socks, ring, gloves;” another, including “wedding ring, gloves.” The diary also has a page headed “Sanfrancisco”[sic], which amounts to a laundry list: nightshirts, drawers, hankies, collars, etc., presumably also for the wedding trip. On October 26, 1870, he records leaving for a trip to Nanaimo with the governor — presumably again serving as a personal attendant. Eventually Colston was back delivering mail for the governor but it is not clear if he still had to dress his handicapped master in the morning.

The work of a valet to a master with a disability would have added to Colston’s responsibilities for he helped the governor deal with the latter’s medical issues. The vice-regent had been crippled in a fall from his horse in November 1869 and also had an attack erysipelas (a serious bacterial infection and skin rash affecting the legs) and so, for example, in July 1870, Colston records bringing “medicine” from the pharmacist A.J. Langley, a druggist on Yates Street, and later taking Musgrave’s crutches into town to be mended. As the governor’s condition improved, Coston helped to move him on a lay chair and fetched stationery to and returned books from a “library,” probably Thomas Hibben’s on Yates Street. He also picked up tobacco in town for Musgrave.

As odd-man, Colston rode to the Esquimalt naval base with invitations to the Queen’s birthday dinner and ball on May 24. Describing his work for this formal occasion, the diary reveals how much business Government House brought to local commercial establishments. On May 17, for example, he fetched “china, lamps, glass” from T.J. Burns at the American Hotel on Yates Street. On May 19, he was again “bringing stuff “ for the ball. Such formal occasions also necessitated purchase of extra food supplies. And so, for example, he picked up bacon from Heywood the butcher at Yates and Broad streets; cocoanuts from Fell and Finlayson’s on Fort Street; biscuits from Piper’s confectionary on Government Street; and prawns from the Colonial Hotel on Johnson Street.

Sometimes, as odd-man, Colston carried out the gubernatorial family’s private business, depositing money in a bank, paying bills, and cashing cheques, the latter especially for Musgrave’s sister, Zöe Musgrave, who was acting chatelaine until the her brother married in June. Zöe also used Colston to fetch books and gloves for her in town or, for example, to take flowers to Mrs. Justice Crease and “cards” to Mr. Justice G.A. Walkem. Presumably for one or both of Musgrave’s sisters, he fetched perfume from A.J. Langley, the druggist. The governor’s private secretary, Anthony Musgrave Junior, had Colston pick up shirts and ties from W. and J. Wilson’s on Government Street.

After the May 24 celebration, he was working in the kitchen. “helping Smith” (the butler or housekeeper?) “cleaning plate,” then, after another dinner party, “helping Smith cleaning plate”.

As odd-man, Colston also served as a coachman. On March 19, he drove the governor into town, “the first time since the accident.” As well, he occasionally drove the vice-regal couple about, for example, to Langford and Colwood for an “airing.” On one occasion, he served as an oarsman for their boat on the Gorge.

Sometimes he functioned simply as a handyman, moving furniture, cleaning the windows on the private secretary’s office, repairing “Mrs. Scully’s stove” and fixing a leak in the roof. Surely expecting Colston to do all these jobs was stretching Mrs. Beeton’s definition of an odd-man, especially because he was also working as government courier several hours a day.

Later lieutenant-governors also seem to have employed an odd-man, expecting footmen to perform a wide variety of tasks at Cary Castle. In 1872, for example, one William Buckett is described in the BC Sessional Papers as “in charge of government house” but in 1873, he is only the “messenger.” In 1898, David Ford is a “messenger” in the Papers but in the city directory for that year he is “steward” at Government House. Did these men have to combine their work as messengers with that of odd-men, or were they promoted/demoted? Other Victoria mansions may also have employed odd-men but, because they were privately maintained, their owners may have had access to more funds than did the residents of BC’s Government House and hence had more servants with defined responsibilities. The records do not indicate whether or not the Musgraves had a butler or steward.

Perhaps, in the minds of the Castle’s residents, it made sense to use the courier as an odd-man because when he was not riding in and out of the city he was frequently on the premises. Of course, the reliable Colston must also have had the residents’ confidence — but may also have been exploited by an underfunded household.

The diary’s usefulness to historians has limits. Of the other servants at Cary Castle, Colston refers to only one besides Mrs. Scully and Smith, recording that, on February 8, the “Chinaman [is] on leave of absence,” to return on February 10. Colston does not say why the man was allowed a furlough but perhaps he resented such special treatment or the extra work required of him during the man’s absence. The fact that the Asian was given leave suggests that, a reliable and trusted domestic attendant, he too had the household’s confidence.

Colston’s diary has other limits for researchers. Because it was kept for professional purposes we learn from it little about the private man. His attitude to his employer is hard to ascertain but when, as a footman, serving at dinner parties, he describes the guests as “10 of them” and on another occasion as “80 of them.” Such laconic remarks may suggest the degree of mild contempt felt by a footman serving at table and reflecting a dichotomy of “Us versus Them.”[10] He does not mention his horse or any difficulties he had with that essential beast but, in the mid-nineteenth century, horses were like automobiles today — only when they break down do we complain about them. It would be interesting to know if Colston wore the traditional livery of a footman.

On the other hand, the diary does reveal some of the problems which the residents of Cary Castle experienced living in that mansion. In the 1860s and 1870s, governors and lieutenant-governors were not allotted adequate funds to maintain the Castle and employ sufficient staff. This underfunding began when Arthur Kennedy took up the position of Governor of Vancouver Island in 1864 and the Legislative Assembly refused to provide a suitable residence for him. His successor, Governor Seymour, discovered that, upon his arrival, his salary was already in arrears. For his part, Governor Musgrave found that the wages of servants in Victoria were much higher than they were at his previous posting in Newfoundland. In her diary, Mrs. Musgrave records how she “worried all the morning about bills.”[11] Upon being offered the position of lieutenant-governor of the new province of British Columbia in 1871, her husband declined the post partly because the remuneration was inadequate. In the later 1870s, the provincial government slashed the annual provision for heat and light at the Castle, forcing Lieutenant-Governor Albert Richards to dismiss some of his servants. When Governor General Lord Dufferin and his Lady stayed at Cary Castle in 1876, plates, linen and pictures had to be borrowed from the Trutch residence.

Apart from being underfunded, BC’s Government House, built in 1860 and expanded in 1865, was badly constructed, which explains why Colston was repairing a leaky roof. Colonial contractors were few and relatively inexperienced with the result that Cary Castle, like the “Birdcages,” built 1859-60, had defective roofs, cracks in the walls and dampness throughout. Carpenters and contractors were constantly employed by the government to repair those structural flaws until Government House burned down in 1899. It is unclear if Colston had actually to climb up on the roof to repair that leak but, if so, such dangerous work was surely beyond the duties even of an odd-man whose duties, on occasion, included those of footman and valet, and, in Colston’s case, courier — but using the odd-man saved paying a professional roofer.

Robert Colston, a former royal Engineer, may have disliked his government job(s). If his role as government messenger gave him a certain prestige, he may also have been aware of the sense of social inferiority associated with his position as a domestic servant.[12] His “multi-tasking,” moreover, may have simply worn him out. He did not remain long as odd-man or courier at the Castle and, in 1873-1874, he was again employed on a ship, sailing between Puget Sound, stopping in the San Juan Islands, and at Victoria. At certain times between 1865 and 1874, he seems to have worked at a foundry and possibly a glassworks in Seattle while maintaining his home in Victoria. Twice he records “sending money home,” presumably to his wife and family there. On September 14, 1872, he records that he “bought a doll for [his daughter] Florence.” On December 21 of that year he notes that he purchased “boots for all the children,” giving their names and the cost of their new footwear. (Canadian cross-border shopping is not a recent phenomenon.) Victoria city directories show that one Frances Colston, a widow, lived on Collinson Street between 1882 and 1885, but we have no date for Robert’s death.

*

As is often the case with historic documents, reading them raises as many questions as can be answered. For example, if Colston, as odd-man, was expected to perform as a valet — a function which he seems to have fulfilled on at least two occasions — who, at these times, replaced him as courier? Did the governor have only four servants in 1870? Apart from “the Chinaman,” was Colston Musgrave’s only male servant? If so, how could Colston effectively be both valet and courier? The well-to-do in England employed “odd-men.” Did other upper-class establishments in Victoria such as the Crease family’s Pentrelew or the Trutches’ Fairfield, also employ such a designated servant? Is it significant that, in her diary, Mrs. Musgrave does not complain about a “servant problem?”

Because the colonial government underpaid the governors who in turn could not support a suitable number of servants, the regular presence at the Castle of a youngish, healthy male (as courier) suggested that he could also be used as an odd-man, using all the human energy present in the mansion.

Robert Colston, however, was not an insignificant cog in a great wheel. Not only was his domestic service essential to the operation of Government House but his carrying of messages from there to Legislative Buildings and back was vital to the functioning of the colonial government during those crucial pre-Confederation months of 1870.[13]

*

Robert Ratcliffe Taylor was born and raised in Victoria and attended Willows School, Oak Bay Junior and Senior High Schools, and Victoria College. He has a B.A. in English and History from UBC, an M.A. in History from UBC, and a Ph.D. in History from Stanford. He taught History at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, where he was active in the Local Architecture Conservation Advisory Committee, the Welland Canals Preservation Association and the Canadian Canal Society. He has published in German history, St. Catharines history, and, with Dr. R.M. Styran, the history of the Welland Canals. “Retiring” to Victoria, he has worked as a Docent at the Victoria Art Gallery and has published books and articles on local history. Editor’s note: Robert Taylor has contributed two other biographical essays to The Ormsby Review: A Person of Some Consequence: Attorney-general George Hunter Cary (1832-1866) and The Mysterious and Difficult Hermann Otto Tiedemann. His book, The Birdcages: British Columbia’s First Legislative Buildings, 1859-1957, was reviewed here by Martin Segger.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

*

Endnotes:

[1] Robert Colston, Diary, British Columbia Archives, microfilm A00847(1).

[2] “The Columbia Detachment of the Royal Engineers.” (www.royalengineers.ca . retrieved September 25, 2020; Frances M. Woodward, “Influence of the Royal Engineers on the Development of British Columbia,” BC Studies, No. 24, Winter 1974-75.

[3]Robert Colston, LEVIATHAN ship journal, January-June 13, 1865. (British Columbia Archives, microfilm A00847 [2]) This diary is much less detailed than his later one.

[4] David Maunsell Fonds, British Columbia Archives, PR-2201.

[5] For comparison, the Sessional Papers for 1876 record that the cook at Government House earned $360.00 per annum, including room and board. (British Columbia Sessional Papers, “Return of Employees,” 1877, p. 542, https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/bcsessional; retrieved September 21, 2020.)

[6] Colston to Ball, British Columbia Archives, Colonial Correspondence, GR-1372.40.339a. A the time of this application, Colston had been repairing the roof at Cary Castle, a possibly dangerous task, which may have made him think that farming would be a less demanding occupation.

[7] In the 1890s, an “R. Colston” was farming on Mayne Island, evidently a prominent local, serving to organize social events and acting as a pallbearer. (Colonist, May 31, 1893, p. 2.) This man was probably one of his sons, Robert Christie Colston. (Canada Census 1891, www.bac-lac.gc.ca, retrieved September 30, 2020.)

[8] The details that follow are from Colston’s Diary.

[9] Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management, London: Beeton, 1861, no. 2171.

[10] Similarly, in her memoirs, Jean Rennie, an English housemaid, referred to her employers as “They” or Them.” Quoted by John Burnett [ed.], Useful Toil. Autobiographies of Working People from the 1820s to the 1920s, London: Allen, Lane, 1974, p. 242)

[11] Jeannie Lucinda Musgrave, Diary, October 2, 1870. (British Columbia Archives, microfilm A-00876.)

[12] Colston may have agreed with the comment of an English footman in 1837: “the life of a gentleman’s servant is something like that of a bird shut up in a cage.” (William Tayler, quoted by Burnett, Useful Toil, p. 185.)

[13] This article grew out of my research into the history of Cary Castle. I owe a debt of thanks to Dr. Gillian Thompson and Dr. Gail Campbell who read it in a first draft and offered useful criticism. If my readers have contributions and suggestions to make, our e-mail address is robandannetaylor@shaw.ca

2 comments on “1267 Footman at Government House”

My 3rd great-grandfather.

And Herbert Dodgson (perhaps another odd-man?) married Frances Musgrave, one of Sir Anthony’s sisters.

This was so interesting – as I have little information about Colston. Interesting that he married a woman from the West Indies, as his daughter (Florence Maria) married the descendent of some of the first black settlers in the region (William Henry Oliver Phelps – son of Edward Russell Phelps, son of Mary Cuffe, daughter of Captain Paul Slocum Cuffe) .

I will be checking all your links for more!

Really enjoyed reading this.