#764 Refuge at Hot Springs Cove

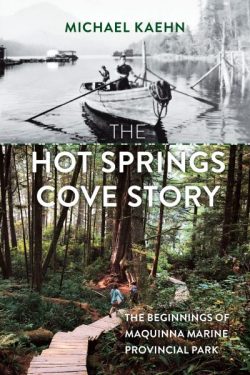

The Hot Springs Cove Story: The Beginnings of Maquinna Marine Provincial Park

by Michael Kaehn

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2019

$24.95 / 9781550178609

Reviewed by Mike Starr

*

Ivan Clarke and his wife Mabel donated the land beside Hot Springs Cove to the Province of British Columbia to create Maquinna Provincial Park. This book, which provides some background to the story of the hot springs and the park, is really two stories; the first, and most fully developed story, is that of Clarke and his family, and the second is that of Hot Springs Cove and the Park, whose history is bound up with that of Ivan Clarke. I found both stories interesting, but even more interesting to me is what they didn’t say. Who was Ivan Clarke as a person? He was apparently a remarkable man, judging by the list of his accomplishments presented here, but accomplishments don’t tell us much about the real essence of a person. And what of Hot Springs Cove? We get glimpses of the place as Mok-she-kla-chuk, “smoking waters,” frequented by the Manhousaht and Ahousaht people since time immemorial for washing, drinking, healing. But how did they feel about this place, and about the settlers like Ivan who moved in and “developed” the cove?

Ivan Clarke and his wife Mabel donated the land beside Hot Springs Cove to the Province of British Columbia to create Maquinna Provincial Park. This book, which provides some background to the story of the hot springs and the park, is really two stories; the first, and most fully developed story, is that of Clarke and his family, and the second is that of Hot Springs Cove and the Park, whose history is bound up with that of Ivan Clarke. I found both stories interesting, but even more interesting to me is what they didn’t say. Who was Ivan Clarke as a person? He was apparently a remarkable man, judging by the list of his accomplishments presented here, but accomplishments don’t tell us much about the real essence of a person. And what of Hot Springs Cove? We get glimpses of the place as Mok-she-kla-chuk, “smoking waters,” frequented by the Manhousaht and Ahousaht people since time immemorial for washing, drinking, healing. But how did they feel about this place, and about the settlers like Ivan who moved in and “developed” the cove?

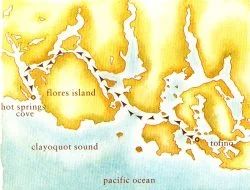

The first chapter, true to the book title and cover photos, is mostly about the hot springs, and acknowledges the traditional use of the hot spring by the Nuu-chah-nulth (Manhousaht Nation amalgamated with Ahousaht Nation, which is one of the fourteen Nations comprising the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council). The chapter also notes visits by early sailors and settler fishermen and sets the stage for the Clarke and Hot Springs Cove stories. We follow the recently divorced (as we find out later) Ivan Clarke, with his pre-emption papers, sales shop goods, tent and two dogs, as he travels to the cove and sets up business.

The second chapter backtracks to Ivan’s parents, and to his birth in Victoria in 1903, where he spent his early years. The chapter provides some leads for interesting family stories, for example the tragic murder-suicide involving Ivan’s older sister and her husband, of which the true story “has never been revealed publicly.” (This is not entirely true; I found the story, submitted by the author, in a 2017 newsletter of the Alberta Genealogical Society, and it would make great fodder for a historical fiction novel.) I can’t help but think that this traumatic event would have had an important effect on the 11-year-old Ivan, and I’d like to know what the author thinks.

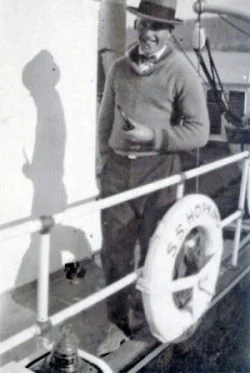

At an early age, Ivan started his career working on boats, and the author describes the various boats in detail, giving us their names, dates of construction, length, and tonnage, the types of log booms or coal barges they towed, etc. This attention to detail applies to many pieces of the story. Mr. Kaehn certainly did his research, but a lot of the detail seems extraneous, even to the story of Ivan, and certainly to the story of Hot Springs Cove (formerly Refuge Cove).

Who was Ivan Clarke as a person? While the author provides a wealth of detail on Ivan’s actions and accomplishments, he only gives us a few direct quotes from Ivan, and even fewer clues to his personality, such as descriptions of his feelings, the quality of his relationships, or his reactions in various stressful situations. There is no mention of Ivan’s reaction when, confronted with a drastically reduced standard of living during the Depression, his first wife Beatrice refused Ivan’s proposed housing, “and the marriage soon ended” (p. 24). However, in a candid moment that reveals something of his fears following the failure of his first marriage, Ivan told his son that he kept his second wife “barefoot and pregnant” so she would not leave him (p. 97)!

I only found a few other moments in the book that gave clues to Ivan’s emotions, such as when he reacted angrily to the schoolteacher who, when Ivan and his family were attending a Sunday religion class, criticized his smoking in the schoolhouse. Ivan is reported to have said, “Come on boys, we are out of here!” (p. 97).

The author had a prime opportunity to explore Ivan’s feelings when confronted with the tragedy of the accidental death of his son, Billy, of carbon monoxide poisoning on his fishing skiff while docked at Hot Springs Cove. Instead, he reports the funeral arrangements and appointment of an executor, and goes on to other stories in the next paragraph (p. 130). The sudden death of Ivan’s wife, Mabel, was another missed opportunity. We hear about the transportation of her body, the top-of-the-line casket and funeral services, and then we’re back to news about yachts and passenger ships, with no report, or even speculation, about Ivan’s feelings (p. 138). I feel like I have just read dozens of factual newspaper stories about him, but that I don’t know the real Ivan Clarke.

How did people at the Ahousat First Nation community feel about Ivan, and the hot springs? The book doesn’t say in so many words, but the author does report a lot of interaction with Indigenous people. The first known photo of what became Hot Springs Cove was from the 1860s, and featured “Sailors from a British Man-of-War Purchasing Salmon from the Indians.” The Indigenous people in the area were willing to trade with the newcomers beginning from the first European visits to the West Coast, and continuing into the 20th century. The trade was mostly carried out from boats until Ivan Clarke set up the first land-based store in the Cove. The location of a Nuu-chah-nulth (Ahousat) village at the Cove, and the prospect of trade with them, as well as with people from the fishing boats that took refuge in the Cove in stormy weather, influenced Ivan to locate his store there.

Over the years, Ivan had many dealings with the Nuu-chah-nulth people: he purchased fish and masks (and commissioned an Orca carving), and he sold them supplies; he also sold their artisanal work in his store, and invited them for annual Christmas feasts. Ivan’s children played with children from the Indigenous community, who sometimes attended the same school. It would have been interesting to interview some of the elders to ask them what they remembered, or what had been passed down through oral history, about Ivan and about the hot spring. As it is, the book is based on many documents, giving the perspectives of those writing the articles, who tend to be settlers, and on oral interviews with Ivan’s offspring.

Despite its shortcomings, the book offers an interesting look at a portion of Vancouver Island’s West Coast during a transitional period of its history. The transitions continue today; in 2017 the provincial government contracted with the Ahousat First Nation to manage Maquinna Provincial Park. Given the millennia-long association of Indigenous people with the hot spring, I find this entirely fitting.

*

Mike Starr (M.A. Canadian Studies, Trent 1992), retired in 2017 from Parks Canada, where he had spent 24 years as an interpreter, planner, and manager at three different national historic sites, most recently Fort Langley. He now does writing and editing from his home on the Sunshine Coast. Contact him at mike@prose-star.ca

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#764 Refuge at Hot Springs Cove”