#694 My name is Lane Winslow

A Deceptive Devotion: A Lane Winslow Mystery

by Iona Whishaw

Victoria: Touchwood Editions, 2019

$16.95 / 9781771513005

Reviewed by Kim Naqvi

*

“He doesn’t seem like the romantic type. I mean, he’s kind of old.”

“He doesn’t seem like the romantic type. I mean, he’s kind of old.”

“The world is full of mysteries, Constable.”

Clever dialogue, and an ear for human flight and fumbles, places Iona Whishaw’s Lane Winslow mysteries in the “cosy crime” category. Expecting to be intellectually challenged and entertained, readers follow Winslow — retired spy and aspiring poet — and her police friends. They needn’t fear being dropped into a black pit of existential despair or the gruesome horrors of humankind’s worst atrocities. Still, Whishaw acknowledges the harsh realities and complex motivations underlying her chosen genre. Deceptive Devotion opens with a sudden, shocking killing. In a two-paragraph prologue, the reader enters and leaves a victim’s body in his last astonished moments. The body remains undiscovered while a tapestry of post-war innocence, ignorance, romance, infidelity, intrigue, heroism, egotism, geopolitical machinations, revolution, village gossip, displacement, and neighbourliness is woven into a credible context in 32 concise chapters over almost 400 pages.

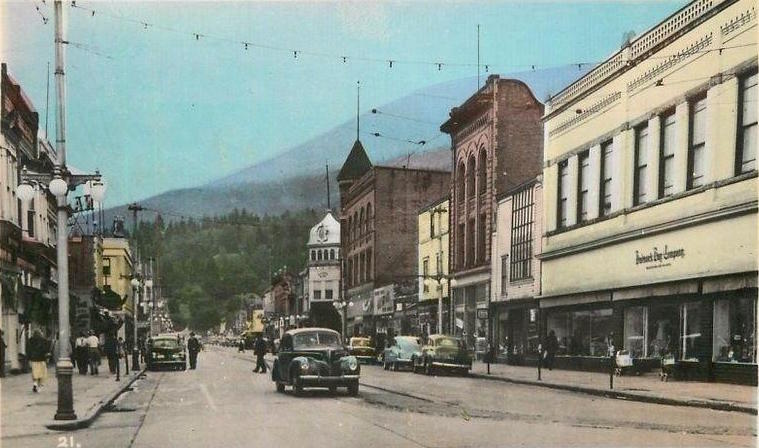

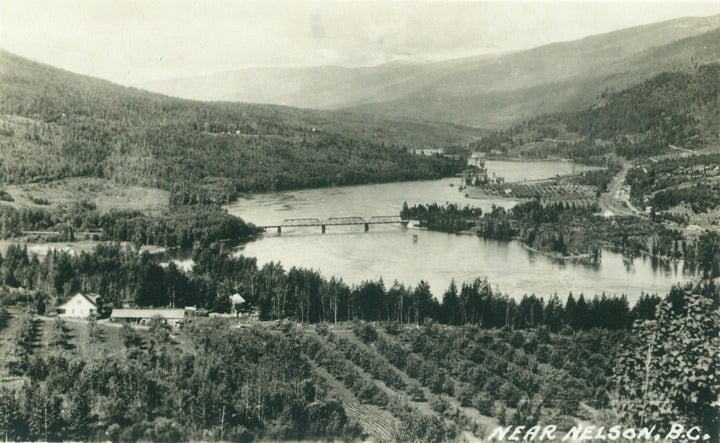

Such a structure could become formulaic. But Whishaw, a retired school principal and social worker, is also a poet, writer, and well-travelled daughter of a geologist father and a mother who was a wartime spy. She is able, through carefully chosen words and characters, to create complexity beneath a superficially idyllic 1940s Kootenays. No question, this book is for entertainment and relaxation. But it does not ignore the world or impose characters who are too supercilious or self-consciously clever to inspire engagement.

After leaving the reader with a September corpse, Whishaw takes us back to July, to the casual but deadly gossip of Soviet bureaucrats sharing vodka and cigarettes at a dacha. It’s an effective reminder that the Kootenay’s orchards and homesteads co-existed with an escalating Cold War, and that the world was recovering — at best — from six years of bloody chaos. Senior agent Aptekar, introduced in previous Lane Winslow mysteries, realises he is not safe in the new Russia. Back ahead to September and a stray Russian countess, Orlova, is deposited on Winslow’s doorstep in need of housing, translation, and her missing brother. From there, the book follows Aptekar, who is fleeing exile and execution, and Orlova, who is seeking remnants of a shattered past. A cold war underworld of displaced people, reconstructed identities, and precarious lives is credible, if less familiar, part of 1940s postwar Canada. Whishaw makes it ring true.

Side stories keep the reader engaged. The entertainingly named Inspector Darling and Winslow are to wed, to the delight of overexcited locals. Constable Ames seeks his sergeant’s stripes in Vancouver and helps Darling track the countess’s brother. Fortunately, Ames and Darling are often on the phone, their banter being one of the series’ highlights. An adulterous couple argue over how to deal with the violent cuckolded husband roused by their affair. The police station, with its small cast of characters, suffers a replacement constable of unknown quality. Finally, Lane’s old nemesis, boss, and lover messes about in the background, inexplicably involved in Aptekar’s case and reminding us that not all love is lovely.

One can imagine Whishaw’s pleasure in creating Orlova, who quickly emerges as more than she seems. As a small woman over sixty she is constantly dismissed. Track the references to “old” and “elderly” woman — it’s more fun when you remember that Whishaw is also over sixty. Talented, intelligent, strong willed, and passionate, Orlova strikes Winslow as someone whose abilities probably never found their proper outlet. As a young Orlova’s father sadly observes, “the world would not part for this giant of a girl.” Whether Orlova is friend or foe is much of the mystery.

The ugliness of war, ideological passions, ambition, and ego finally converge; Whishaw’s fictional sleepy hamlet of King’s Cove, Kootenay Lake, is allowed to move forward while a new set of wounds heals.

In a recent blog, Whishaw reflected on the similarities of poetry and mysteries, which are seemingly at opposite ends of the literary spectrum. She notes that “[b]oth deal in spiritual uncertainty, and both explore the very gritty core of what it means to be human.” At the heart of crime mystery is human motivation, an elusive quality that we all share. As Darling advises Ames:

We never, with all that we do, can know the full story of someone’s murder, the full deep reason why someone would kill someone else, and what those last minutes were like. But we are humans, and there is a certain amount that we know about the world around us from what we feel, and while those feelings do not constitute forensic evidence, they can sometimes be an indicator that we need to look more deeply….

Thank you sir …. I don’t think that part about feelings is in the sergeant’s manual, by the way.

Mystery writing often overcomes formula through the use of supporting characters who ground fantasy in recognisable details and plausible feelings and emotions. More than most genres, mysteries repeat characters and locations. Their cosiness can come from old relationships featuring and emerging in ongoing stories that are larger than one crime. Whishaw’s regulars remind us that wars, revolutions, and the appalling loss of young men in wartime mark everyday lives and landscapes; that humour can and does stand in for open expressions of love and respect; that madness might merely be repressed honesty; that minor characters have lives and histories as complex as the lead; and that, given its impact on daily life, doing the dishes gets far too little literary attention.

*

Kim Naqvi is a native of the Canadian prairies, and a prairie kid at heart, but has lived in the BC Interior for most of the past 12 years. She teaches human geography at Thompson Rivers University and has a special interest in the meaning of landscape, and the absurdity of contemporary economic practice and culture.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#694 My name is Lane Winslow”

Comments are closed.