#680 All hat and no soapbox

Mad Hatter

by Amanda Hale

Montreal: Guernica Editions, 2019

$29.95 / 9781771833905

See here for the audiobook

Reviewed by Linda Rogers

*

Don’t judge a book by its cover … at your peril. That’s a song worth listening to but sometimes, and in this case, it is all there, the rabbit’s final bone crushing scream. As the subject, an archetypal pre-Brexit Englishman, dressed in his morning coat and high self-esteem, gradually sinks into the sea, the sea, the sea, Iris Murdoch’s agonized diminishment, we are familiarized with the intoxication of suffocation.

Don’t judge a book by its cover … at your peril. That’s a song worth listening to but sometimes, and in this case, it is all there, the rabbit’s final bone crushing scream. As the subject, an archetypal pre-Brexit Englishman, dressed in his morning coat and high self-esteem, gradually sinks into the sea, the sea, the sea, Iris Murdoch’s agonized diminishment, we are familiarized with the intoxication of suffocation.

Here is it straight from Wikipedia: “Erethism, also known as erethism mercurialis, mad hatter disease, or mad hatter syndrome, is a neurological disorder which affects the whole central nervous system, as well as a symptom complex, derived from mercury poisoning.” That was then. Now safer practice has removed the mad from hatters.

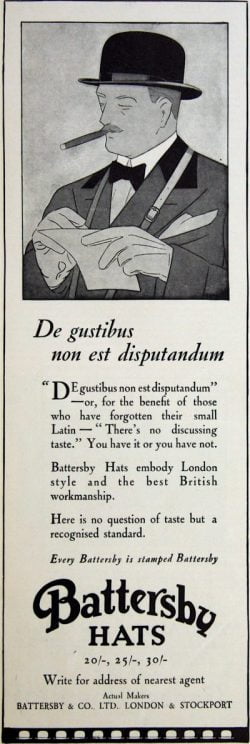

The charismatic central figure of Hale’s scrupulously researched historical novel is an upper middle class Englishmen in the garment trade. His family owns a hat factory. Christopher Brooke, to all appearances a gentleman, aspired to universality. He enjoyed the perquisites of the moneyed class while maintaining allegiance to the craftsmen who represented the tradition that created his prosperity.

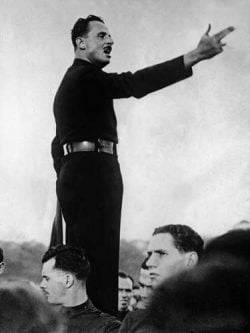

He may, as Hale — wearing two hats: faux biographer and daughter — suggests, have sniffed the glue, a perfectly logical explanation for his fanatic allegiance to the paradoxical politics of the fascist Oswald Mosley and his National Union party, which asserted the dignity of working people, the same sort of ideology which is the impetus of Brexiters today. That is a lesson not lost on Hale, who subtly, almost inadvertently, reminds us of historical parallels without overt didacticism.

If it weren’t for the Second World War, a real threat to his sovereign nation, Christopher may have been just another eccentric Englishman, standing on a soapbox in bespoke garments.

But England, with its ancient feudal governance, a class system that manifested clan loyalties across Europe and dominated an Empire of feeder economies based on slavery and colonial occupation, deceived itself with the principle of fairness, jolly old fair. Fair was punishing dissenters from the norm, whether by internment for foreigner nationals, chemical castration in the case of the hero decoder who saved the country from annihilation, or silencing the great two-spirit poet whose spirit was broken in Reading Gaol.

The echoes of make America Great Again reverberate in the Mad Hatter, a portrait of xenophobia.

The echoes of make America Great Again reverberate in the Mad Hatter, a portrait of xenophobia.

Christopher was a gentle/man who, like many Englishman right up to the Prince of Wales, descended from barbarian tribes latterly emulating the refinements of high German culture. His fictional daughter remembers his graceful wrists, hovering like Anglo-Teutonic bridges over troubled water as he played Liszt’s lyrical Liebestraum, a favourite German tune. But German was no longer comme il faut. Decent anti-Semitic Englishmen had to be appalled by Nazi ideology. Those allegiances had to be broken. Bosch was Bosch, as verboten as Kike or Wog in public discourse, and dissenters were rounded up and punished.

Canadians take note. It happened here in labour and internment camps in both wars.

Why did Christopher persist, despite the entreaties of his suffering family, despite ostracism and imprisonment, the humiliation every public school boy fears? He may have been made mad by incarceration. Madness is often congenital, but there are social possibilities. He was in trade, not quite gentry. Gentry owned land and titles as old as the land. Maybe the quintessential Englishman, Christopher was still an outsider to the ruling class and may have believed his allegiance to Mosley and the wayward prince defined him as “more.” That, plus the noblesse oblige of supporting workers’ rights.

We will not know. Others reveal aspects of the story: his children, Mary Byrne, the Irish servant, whose endearing portrait of a family is made intimate by her revelation of familiar things, and smaller players in Christopher’s constellation of appalled acquaintance.

Amanda Hale is one of those children. Part fiction, part memoir, Mad Hatter is a portrait of a family and a very difficult one to paint because everyone is moving, some hiding behind obtuse family furniture, others long in the underworld of death. As ever, Hale maintains her searing integrity, a cauterising effect as she describes the injuries that begin with the mother wound, the circumstance of her conception and birth. With ruthless attention to detail, she keeps her story focused and the characters on their relentless paths to now, because the present manifests the past. Mad Hatter is the portrait of a time, framed in historical reference but made real by her artist’s eye and determined integrity:

I won’t pretend that my story is factual. I imagine a man I never knew, creating what I cannot uncover, adorning him in top hat, bow tie and winged collar, a mad hatter. In dreams my silent father stalks me, insistent as he crosses the prison yard and turns slowly to reveal a ticking clock embedded in his crushed head.

Holding the book and the family together are the minor characters whose degrees of separation lend credibility to speculative events: Mary the humane Irish housekeeper and her hapless sister Deirdre who delivers a tragic-comic surprise as the book slowly runs out of breath, the third time under waves that compute and complicate this sexual almanac.

Sex is Hale’s glue of choice. Degrees of desire, fatal attraction, compose the sticky medium that attaches wife to husband, servant to master, and child to parent. In the grey fog of post-war England, heat is a beacon and too often a false indicator of real warmth as the cold element gradually pulls this story in. Christopher, the false prophet raging at the dying of the light, imminent submersion, writes:

In Britain nothing stays still, the sky, a constant presence opening up then bearing down, changeable. So we must endure. The light illuminates my wedding band, a circle of fire around my finger. I will not remove it, come what may.

Christopher remains an enigma, a man slowly drowning, weighted by his own tropes, dragging his family down with him. His gathering storm is a panic that suffuses Amanda Hale’s childhood rooms of memory and desire with the smells and sounds of diminishing innocence:

The head of our family was missing and I, a slow but persistent swimmer and believer in magic, spent my childhood diving for him, over and over, coming up gasping for air; not knowing whom I sought.

This carefully researched and beautifully written novel is the basket of eggs its author has carried all her life. Eggs are not an easy inheritance. Just as every woman carries her grandmother’s primal shapes in her ovaries, so Hale is called on to balance her fragile baggage, the secrets and lies and yes, the beautiful notes that are at once a painful lament and a soaring dream of love, Leibestraum.

*

Linda Rogers’ recent book is Yo! Wiksas? Hi! How are you? (Exile Editions: 2019) with artist Chief Rande Cook, and she is about to move on Repairing the Hive, third book in the Empress trilogy, and the collaborative Arioso Game with Ben Murray, shortlisted for the BC Great Novel Search. She is also working with fellow writers and artists on Mother, the Verb.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#680 All hat and no soapbox”

Comments are closed.