#635 Go east, young man

A Voluntary Crucifixion

by David J. MacKinnon

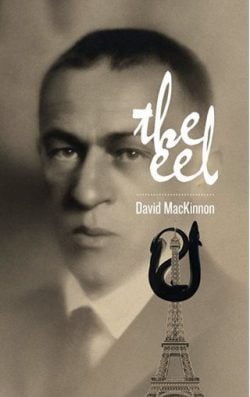

Montréal: Guernica Editions, 2019

$25.00 / 9781771832724

Reviewed by Jim Christy

*

If you’ve ever heard of David MacKinnon, where have you been? Certainly not around the literary scene anywhere in Canada, including his native British Columbia, even though he is arguably one of the best writers in the Province – and I’ll argue it.

If you’ve ever heard of David MacKinnon, where have you been? Certainly not around the literary scene anywhere in Canada, including his native British Columbia, even though he is arguably one of the best writers in the Province – and I’ll argue it.

If you know him as a writer you must be familiar with the Parisian literary world because he has had novels brought out to acclaim in Europe with Éditions Denoël, France’s most prestigious publisher. Or perhaps you know what’s going on in the Netherlands, where he has a distinct writerly presence.

Academia? MacKinnon read history at UBC, Louvain, and the Sorbonne and holds degrees in both the Civil and the Common Law”

A lawyer, MacKinnon has defended clients whose health was damaged by asbestos, translated for international tribunes in Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and become a spokesperson for Indigenous land claims.

If you’re a worker you might have come across him on the docks of Vancouver or on the oil rigs in Alberta, or perhaps it was in that toilet factory or the hospital where he carted amputated limbs to the incinerator.

MacKinnon has lived in China and Madagascar, and travelled over much of the rest of the world.

This wide experience: working, travelling, law, and academe have gone into his work, the novels Leper Tango (2012) and The Eel (2016), and most particularly the most recent, A Voluntary Crucifixion, his literary memoir.

It’s a deep well into which other Canadian writers can’t drop their little buckets.

The hero of this book, one David MacKinnon, is driven to escape what he early on realizes is, and will continue to be, a stultifying life, too small for his dreams. The title is a nod to one of his literary heroes Henry Miller, only MacKinnon’s crucifixion is not Rosy at all.

Miller needed to sink to the bottom to discover life but then he didn’t have that far to fall. His father and mother were German immigrants, the father a tailor. Instead of descending from the Lower-Middle, MacKinnon’s precipitous descent began at the Upper. He hails from a fine clan that originated in the Scottish highlands, and who came to this country during the infamous “clearances” that saw the Scots Highlanders displaced from their lands. MacKinnon’s were in Nova Scotia when Canada was barely a country.

He grew up in New Westminster where his father became a B.C. Supreme Court Judge, a solid, old money, old world figure, a conscience that would always be there looking over his son’s shoulder whether the son is doing good by defending the rights of people whose lives have been ruined by asbestos, drunk in an alley in Cairo, wallowing in the fleshpots of Hong Kong, surviving desperate romantic entanglements on several continents, or organizing hundreds of Indigenous people from around the world to march on Rome and confront the Pope with the object of convincing him to admit the crime of the Papal Bulls of 1455 and 1493 that presumed to give Catholic explorers the right to seize and exploit any and all lands they might “discover.” As for the people therein, they didn’t matter because, Tsotsi, Maori, or Cherokee, they weren’t fully human.

Our hero leaves Canada as a young man seeking the world in general and the City of Light in particular. He makes the odd trip back to Canada to work, for instance, at a big deal law firm in Québec where lawyers bill more hours in a week than there are in a week. Not only is the firm corrupt but everything else is too, particularly the government.

There’s a vignette set in a Montréal firm where two lawyers are detailing their proud chicanery. It’s like listening to a pair of Dadaists or a conversation between George Burns and Gracie Allen.

The scenes shift abruptly which lends a certain lightness to the narrative: to Coquitlam, where MacKinnon is living in a basement apartment and working the kiln at the Crane Pottery Works; then he is a roughneck in Alberta. Later, it’s Hong Kong where he is falls in cahoots with a Chinese conman. “James Lee was his fourth name….” He also called himself Joseph, Romeo, or “just plain Lee Fook Lam.”

A subtle theme throughout the book is the parallel between the displacement of Indigenous peoples and that of his Catholic highland ancestors. It’s not a wild leap to compare the Trail of Tears with the diaspora out of Scotland.

Spin the kaleidoscope and MacKinnon is lost in Madagascar, “… at a malaria-infested hole at the end of RN 12 running due south from Irondro.”

Most writers would use up fifteen pages to try and fix that locale in our minds only to bog us down in a swamp of verbiage. MacKinnon does it in a few words or a few bold strokes. “My life is a series of jagged frescoes, torn from the canvas….”

Leaving aside the fact that frescoes aren’t done on canvas but directly on to wet plaster walls or ceilings, the analogy is apt. Furthermore, MacKinnon has carefully prepared the wall, knows his craft and his tools, and has done his work before the plaster has a chance to dry so that the colours are sure to take hold. His colourful story will last long after the dry work of most Canadian novels has dimmed and faded.

*

Jim Christy is a writer, artist and traveller; he recently celebrated his 74th birthday by hitchhiking across the country, from Mission, B.C. to West Modeste, Labrador.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#635 Go east, young man”

Comments are closed.