#561 At home with Jack Hodgins

Damage Done by the Storm

by Jack Hodgins

Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2019

$18.95 / 9781553805595

Reviewed by Ginny Ratsoy and Alexandra Horsman

*

First published by McClelland and Stewart in 2004, this collection has been reissued with one story added. We are happy to report that Damage Done by the Storm withstands the test of time. Although the setting and scope of the eleven stories vary, each evokes disquiet as they explore human connections and inner tensions. Like the Alex Colville paintings and Alice Munro short stories that most stay with us, these works range from vaguely disconcerting to highly unsettling, as they probe “the ordinary.”

First published by McClelland and Stewart in 2004, this collection has been reissued with one story added. We are happy to report that Damage Done by the Storm withstands the test of time. Although the setting and scope of the eleven stories vary, each evokes disquiet as they explore human connections and inner tensions. Like the Alex Colville paintings and Alice Munro short stories that most stay with us, these works range from vaguely disconcerting to highly unsettling, as they probe “the ordinary.”

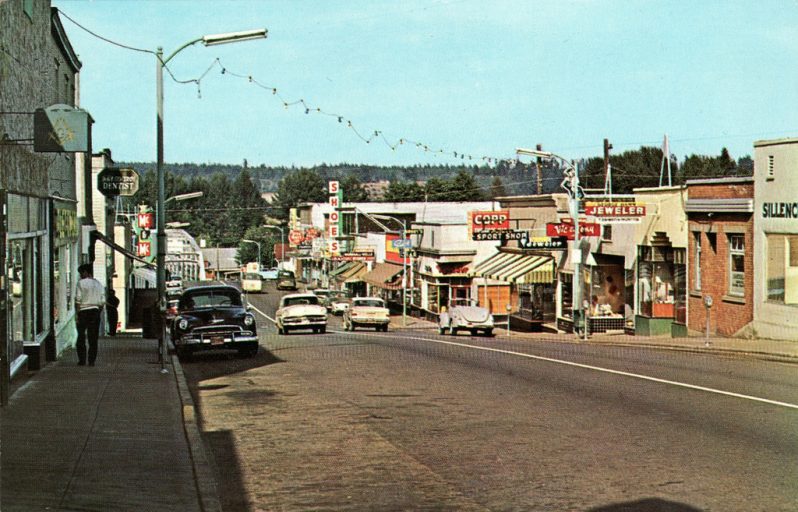

Jack Hodgins, in a 1978 interview with BC Bookworld, stated “You carry your own home around with you” in reference to the effect of his own upbringing as a loner in the relatively isolated settlement of Merville on Vancouver Island. Despite his subsequent recognition as a writer (in the form of several Honorary Doctorates, the Governor-General’s Award for Fiction and the Canada-Australia Award, among others) and an academic career that is international in scope, both the attraction to and rejection of home continue to preoccupy his writing.

Setting and characterization are inextricably linked. The Island represents the seldom-bridgeable distance between humans in both “The Crossing” and “The Drop-Off Zone,” with the ferry to the mainland acting as a limbo between one world and another. In settings further afield (the southern U.S. in “Galleries” and Ontario in the title story, for example) the gaps between generations and “close” relatives are magnified by travel. His characters, although often outwardly solid and settled, whether young or aged, are often inwardly incomplete, isolated, even precarious — at times removed from their own lives. Typically, theatrical or other artistic metaphors are employed in the service of protagonists who are occasionally artists but more often artists manqué — and seldom able to move from enactment to actuality.

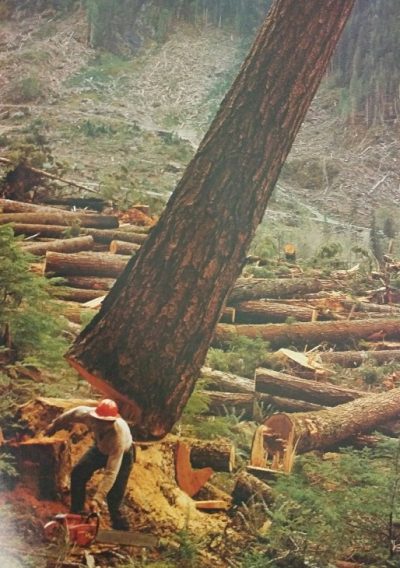

Although Hodgins returned to the comedy and magic realism of his first novel, The Invention of the World, as recently as 2014 with the novel Cadillac Cathedral, few stories in Damage Done by the Storm fit that profile. Perhaps the notable exception is “The Drover’s Wife” in which protagonist Hazel approaches Vancouver Island as a place for reinvention of the self, and her creator sees her as a vehicle for myth making. In Robert Duncan’s 1981 National Film Board documentary, “Jack Hodgins’ Island,” Hodgins stated that people migrate to the island “for very special reasons, often to leave behind undesirable places.” The island’s quality of being a place of “new starts” and opportunity proves magnetic to Hazel, who leaves her old life and family behind in Australia. She refuses to be defined by traditional gender norms and manages to make a fortune in the male-dominated logging industry. Though she is hardworking, she also earns a reputation as cold and stubborn. These traits turn her into an almost mythological being on the island; however, she never appears to make any deep and lasting connections. Hazel, free, independent, and outwardly successful, is also alone. Her experience mirrors both the myth and reality of island.

Incipient myth-making is evident in “Over Here,” which is (not atypical of Hodgins’ earlier short stories) a rite-of-passage story of a narrator looking back on his working-class island childhood. The narrator remembers his exoticized fantasies of Indigenous history as ironically removed from the reality of his relationship with an Indigenous classmate, Nettie, whose ancestry he believed he was one of the few to know. His father served as a gentle de-mystifier, gradually initiating his son into harsh realities that not only uncovered the racism of the community (and the beginnings of it in the son himself) but also led the son to the uncomfortable truth that the two of them, with their history of a disappeared wife and mother, were stigmatized in the community, too. The story opens with the father teaching the son the process of stripping bark from the cascara tree – a graphic metaphor for both colonial devastation and community pretexts. When, at the story’s denouement, the father states, “Maybe there’s more than just one plot out there,” the son de-romanticizes his own heritage and assumes the role of an Indigenous warrior.

The familiar Hodgins backdrop of “stump ranches, logging trains, and pickup trucks” also informs “Promise” where, again, an adolescent male protagonist’s dreams are measured against a hard reality. The story follows a family who receives an unexpected visit from the father’s old school principal. Initially, the principal appears to be a man to admire. He is an educated man who had encouraged the father to strive for more in life, having seen his potential. The father, in contrast, is depicted as a well-respected, hardworking man who never strove for more than the security of a job at the logging company. “Promise” makes the reader question societal values. The principal, who from an outside perspective appeared to be a man to respect, in reality turned out to be a conman who only reached out to the boy’s father to sell insurance. Conversely, the hardworking father is revealed to be the true hero of the story, as he encourages the boy to follow his dream of being a filmmaker.

Monty in “Balance,” the collection’s first title, achieves only a secondary feeling of artistic satisfaction through his role in the production of orthotics. This story also deals with the theme of understanding people through superficial lens. With a failed romance behind him, and merely perfunctory communication with his co-workers, he projects his feelings onto his geographically distant customers, personalizing the recipients of the footwear inserts to the extent that he falls in love with one of them. This Pygmalion, given only the name and location of one of his clients, invents a life for her and initiates written communication, thereby endangering the employment that facilitates the removed relationship in the first place. “Balance” ends with Monty recognizing the limitations of his artistry and his inability to bridge the chasm between imagination and execution — aware that his craft is remedial to him, as it is to the recipients of the orthotics.

Like Monty, Nathan in “This Summer’s House” is an artist-once-removed — wilfully. Nathan consciously forsook his photography because engaging in it made time pass too quickly. However, his vocational substitution, house painting, proves unsatisfying. What is sublimated must resurface in some form; in Nathan’s case it is stage designing — not only in theatre but also in the series of summer homes he and his wife rent. In particular, Nathan attempts to stage the annual visits of their offspring as theatrical productions. In fact, all aspects of his transient summer life have an air of unreality to this Walter Mitty — until a younger man whom the renters displace forces Nathan to confront the reality of the impermanence of the family visits and the class divides that would render the man homeless. The curtain has come down on Nathan’s production.

The limitations of family relationships is also central in “Inheritance,” a novella within the collection of short stories that offers us two different aspects of the theme of isolation. First, Hodgins explores the façade around family and friendship when the two protagonists of the story, Frieda and Eddie, are named heirs to an uncle’s estate. Upon learning of the inheritance, those around the couple begin to turn on Frieda and Eddie out of jealousy, wrongfully accusing them of deceit. Second, the debilitation that often accompanies aging is a facet of isolation explored through Frieda’s gradual mental degeneration. Though her illness is not overtly apparent in the story, she appears to be forgetful and require assistance occasionally to remember details: her reality is fragile on several fronts.

Geographic distance, unfaithfulness, and mental deterioration are responsible for the solitude in “Astonishing the Blind.” A middle-aged Canadian musician performing and living in Germany, unable to return home to celebrate the 60th anniversary of her parents, writes a letter to her father (who is coping with an enfeebled wife) recounting her experience performing in a town filled with blind people, whom she set out to astonish in her first concert there. Only near the end of the story/letter does she reveal that her husband is having an affair. “Astonishing the Blind” ends with her appreciation for the rarity of lifelong love she has witnessed in her parents and her promise that her next concert will be dedicated, not only to astonishing the blind, but also to her parents’ marriage. Although she has not travelled to them to celebrate their anniversary, nor even phoned in her congratulations, the art (both the music and the letter) is her gift.

A veteran at exploring the depths of isolation, art, inner turmoil, and dysfunctional relationships — and the connections therein, Jack Hodgins has, with Damage Done by the Storm, produced an absorbing collection of short stories. His emphasis on home and place engenders relatability, regardless of the reader’s familiarity with a particular setting. Damage Done by the Storm continues to demonstrate Hodgins’ talents as an author and has us looking forward to what may come next.

*

Ginny Ratsoy is Associate Professor of English at Thompson Rivers University, where she teaches Canadian Literature and delights in mentoring promising undergraduate students through service learning, research, and co-writing for The Ormsby Review. Alex Horsman is an undergraduate student at Thompson Rivers University, majoring in History and minoring in English. This is Alex’s first time co-writing a book review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher: The Ormsby Literary Society

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#561 At home with Jack Hodgins”

Comments are closed.