#542 Classical, biblical, theoretical

Passageways

by Philip Resnick

Vancouver: Ronsdale Press, 2018

$18.95 / 9781553805236

Reviewed by Andrew Parkin

*

This book is a selection of poems reaching back more than four decades. Unsurprisingly, we experience an array of subjects and themes expressed mainly in free verse but with very occasional rhymes. The subjects derive from Resnick’s reading and teaching as a professor of Political Science at the University of British Columbia, from his many travels to conferences worldwide, and from his family holidays with his late wife. This impressively disparate volume culls poems from Resnick’s Poems for Andromache (Pelion Press, 1975) and The Centaur’s Mountain (Pelion Press, 1986). Passageways proclaims the Greek influences in its first section, Of the Greeks and Hebrews where we discover themes from what at UBC was dubbed “Classical and Biblical Backgrounds.” Although grounded in the pre-Roman world, this poetry has a striking contemporary voice concerned with abiding themes and concerns.

This book is a selection of poems reaching back more than four decades. Unsurprisingly, we experience an array of subjects and themes expressed mainly in free verse but with very occasional rhymes. The subjects derive from Resnick’s reading and teaching as a professor of Political Science at the University of British Columbia, from his many travels to conferences worldwide, and from his family holidays with his late wife. This impressively disparate volume culls poems from Resnick’s Poems for Andromache (Pelion Press, 1975) and The Centaur’s Mountain (Pelion Press, 1986). Passageways proclaims the Greek influences in its first section, Of the Greeks and Hebrews where we discover themes from what at UBC was dubbed “Classical and Biblical Backgrounds.” Although grounded in the pre-Roman world, this poetry has a striking contemporary voice concerned with abiding themes and concerns.

In effect, we follow Ariadne’s thread through the perilous labyrinth of modern history to confront our 21st century Minotaur, the present state of affairs. But our affairs are not new; only the technology of murderous war is new. All, however, is based on our all-too-human needs. The poet hears the “Aegean/ rolling in…” and “…it is as though a Sophoclean chorus/ were warning of approaching storms” (p. 9).

“Iphigenia” leaves no doubt about the power of the ancient stories told across the centuries. The poem starts with “Snow is falling over Montparnasse/ as we leave the cinema,/ sacrificial smoke still circling altar,/ unseen blade” (p. 7). In the modern movie’s re-telling of the story there is “…no after-life/ no rendezvous at Tauris.” The poem tells us a truth about human “civilization” that exists in the mind and sensibility and not in the external trappings of the world: “Her corpse is but a testament/ to that fine line separating barbarian from Greek,/ civilization from its reptilian brain” (p.7). This poetry records the poet’s ability to read and re-live the myth or lore and see the human truth there.

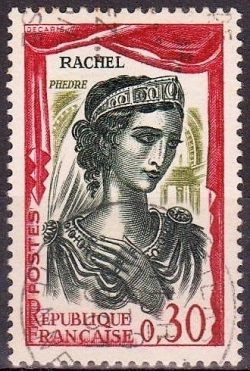

In “Phaedra” a touch of contemporary realism makes its point: “An unlit corridor separates the sweating woman/ from her wish” (p. 6). “In Alexandria” juxtaposes the Hebraic and Greek worlds and favours the good companions of Greece over the Hebraic “…precepts of a rigid code.” The Judaic poems, to me less successful, show that Resnick is Mediterranean Greek more than a strict moralist wandering the desert wastes to find a home.

The next section, Faraway Shores, meditates on youthful experience of such places as the Residencia des Estudiantes in Madrid or the Parisian Cité Universitaire, where the poet and his lady met in the Maison des Etudiants Canadiens. At a similar point in my own youth I stayed in the Maison du Maroc. All that time and world comes rushing back. As do the horrors of the Second World War in “Trade Fair Palace, Prague 1942” and the associated atrocities by Nazi Germany. Hovering there I detect the prophetic ghost of Kafka who studied Law and wrote in German his fable of man as a cockroach. Gregor’s fate foretold more than we or Kafka could imagine.

In “La Maison de Culture, Bobigny” I recognize the notorious suburb, a hotbed of French communism then, where my wife’s grandfather was once mayor. Not surprisingly, Lenin is mentioned in Resnick’s poem. The poem ends with a key phrase for Resnick’s poetry and this entire volume: “…and the ever-receding ancients/ rock us in their arms” (p. 40). In the Prague poem the cruelties of the ancient world are revisited in the Nazis’ public hangings. Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge gives a vivid and detailed account of public hangings with the repellant behaviour of the mob of spectators. This may well have influenced the British to keep their hanging of criminals within the confines of prisons.

The next section, In Troubled Times features poems about modern politics. “Alexanderplatz” jolts me into the Nazi era and Soviet past in post-war Berlin. I read Döblin’s eponymous novel just before I left home for military service. A year later, after a number of secret classrooms, I was standing in Alexanderplatz in East Berlin just to experience it. Going there was not a part of my actual mission. Suddenly loudspeakers announced, “Achtung! Achtung!” The people around me and the entirety of those in the square stood still. After the patriotic announcement there was martial music. People went about their business. My fear of a Stasi or Soviet identity check subsided. I had encountered a feature of “a regime that lived its forty years/ amidst the ruins of a still more hateful one, /snow blowing through Alexanderplatz,/…discordant, shattered lives” (p. 58).

These poems usually speak through realities and circumstances. However, ‘Le défi’ is just a clear statement that darkness is never totally locked away from our hearts; I’d call it a statement more than a poem. “Sans Illusions” is similarly a statement of the political state of play but it has a powerful moment of poetry when “…someone whispers the word ‘democracy,’/ to no avail” (p. 61). It also has a series of rhymes, with “debt” repeated and forming a rhyming couplet at the end, “…a crushing debt/ of promises only rarely kept” (p. 61). This sixteen line poem is almost but not entirely a sonnet. The use of “only” in the last line makes the rhythm more awkward than if the word “so” were used, preserving the metre.

“Fugue” is terse, elegiac, moving. It was written for Liu Xiaobo, the dissident student who faced the tanks in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, was arrested, and died in prison. Readers who want a vision of life in a Chinese prison camp will find a brilliant account in Wu Ningkun’s A Single Tear. But in the era of Chairman Deng one saw big character posters in the People’s Republic of China proclaiming, “Development is Good.” Business growth, international expansion of influence through investment, and technological mastery are now China’s major agenda. But don’t rock the boat. And the old story persists: “Hostages having been taken, Caesar ordered a forced march”!

“The Better Angels of Our Nature” addresses the recent horrors of terrorist politics. The sadists and killers remain even if the plans for a Caliphate are now on hold! The poem’s phrase about the great powers who “play their cloak-and-dagger games” is a journalistic phrase Resnick could have avoided. The “great game” was a famous phrase but concealed the lethal and vicious aspects of ensuring national security, so that we can write and publish poetry. French and British security forces have in fact saved many lives over the last decade by dismantling as many as eighty plots in a year when one or more lethal attacks took place.

“The Paradise Papers” (p. 62), perhaps the best of this batch of political poems, has clarity, momentum, and controlled indignation at the age-old means for corruption that exist and will continue. In “Political Cycles” (p. 65), Resnick shows how politics changes and passions give way before change: we cannot always, thank goodness, “…storm the heavens” (p. 65). W.B. Yeats in old age wrote “Politics.” He asked a question that shows how life is more necessary than sterile, soon to be used up ideas: How can I, that girl standing there,/ My attention fix/ On Roman or on Russian/ Or on Spanish politics?… O that I were young again/ And held her in my arms!” This famous outburst might dismay the earnest politicos but Yeats knew about politics, love, and old age.

Resnick has made contemporary issues from Brexit to Trump’s America the subject of these poems. The verse is competent but his statements are not always poetry, as in Shelley or Byron or the Tennyson of “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” But Resnick’s “Fugue” (p. 59) is a genuine poem not a mere statement. “Europa after the Rain” is a wonderfully compact poem working through striking imagery: “Europe undoes the stitches that bind the wounds…” (p. 68). It works also through references to myth and history, leading to the realization “that dreams and nightmares are really twins” (p. 68).

Resnick has made contemporary issues from Brexit to Trump’s America the subject of these poems. The verse is competent but his statements are not always poetry, as in Shelley or Byron or the Tennyson of “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” But Resnick’s “Fugue” (p. 59) is a genuine poem not a mere statement. “Europa after the Rain” is a wonderfully compact poem working through striking imagery: “Europe undoes the stitches that bind the wounds…” (p. 68). It works also through references to myth and history, leading to the realization “that dreams and nightmares are really twins” (p. 68).

Resnick as an academic knows the trendy “score” of professorial lemmings rushing to the latest academic fad, so his “Postmodern Times” (p. 69) gives a succinct assessment:

Old forms dissolve

as the fragments are rearranged

in a smorgasbord of asymmetrical shapes

with labels like discourse theory,

liquid reality, risk society.

Yet somehow these permutations fail to coalesce

while searing hatreds and warring sects

revivify postmodern norms.

The penultimate line accurately describes a situation in which scholarly enquiry, once a matter of thinking and writing and publishing results that could stand or fall according to discoverable facts and reasoned arguments, has been replaced by pre-enlightenment norms driven by the question, “whose side are you on?” Resnick clearly rejects the posturing of “theory” adherents. Those teachers who have had to work under the yoke of academic theorists will enjoy the eight lines and that rhyme on “forms” and “norms.”

For me, Resnick’s most resonant political poem is “The Lack of Silence” (p. 70). The figure of the old woman opening the poem reopens all the wounds of such civil strife as kills so many for the sake of some idea, or movement, that will be misunderstood and eventually forgotten. No wonder many ordinary citizens are wary of politicos, “thinkers” and the military. “Two Images” (p. 71) uses press photos that recall the Jewish boy in the Warsaw ghetto with his hands up and the recent refugee boy washed up on a beach. A third image most of us have also seen is that of the naked Vietnamese child fleeing a burning village. America isn’t squeaky clean either!

The “Meditations and Reflections” section comprises thirty-seven poems. “Rousseau” starts with the notion that “Jean-Jacques still haunts us” and later sums up the power of his writing: “a pen that seemed to take a Sybil as its guide” (p. 103). The word “haunts” will recall Marx’s famous “There is a spectre haunting Europe. It is the spectre of communism.” In this section political themes find a more powerful treatment than brief opinion pieces; instead Resnick now offers ideas linked to myth as well as history. In “Theomarchy” (p. 100) and “Orpheus” (p. 101) we get the best words in the best order.

“Condorcet” speaks in tones of quiet conviction. Nicolas de Condorcet had written a sketch for an historical framework of the progress of the human spirit. But he lived through the French Revolution until Robespierre’s Terror caught him as another victim of that heavy guillotine blade. In the Place de la Nation over 1500 people from ages twelve to over eighty were guillotined and over three days were trundled off to mass graves dug in the garden behind the Convent in the rue de Picpus on the edge of Paris. Two of the three graves were filled before Robespierre himself was guillotined and the terror stopped. So much for the progress of human beings.

People tried to keep low profiles by wearing revolutionary garb (cf. Soviet dress with caps and Mao suits and caps), but some Parisians and others had finely embroidered silk linings sewn inside the drab costumes. That’s a sign of hope! If they are going to terrorize because of ideology, at least we can cock a snook at would-be Kommissars. Huizinga, that fine medievalist who lived through the Nazi terror, gets a suitably accomplished poem condemning the “barbarous uses of the human mind” (p. 107). In another fine poem “The Hampels,” this couple, Elise and Otto, are tracked by the “Gestapo’s Argus eyes” for distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets. Yet their solitary deaths “leave a fleeting mark,/ a quickened beating of the human heart….” (p. 108).

The dragging of our lives towards our inevitable deaths, Resnick catches unflinchingly in “On Some Lines by Seferis” (p. 112). Yet Resnick’s poems inspired by other writers include perhaps his finest example, “On Re-reading Neruda….” (p. 116). And in “Fidelity” the poet confronts harsh truths about life that we discover by living: “The lines remain faithful,/ even when the flesh cannot” (p. 119). Horace reminds us that “The years as they pass plunder us of one thing after another” (Epistles, Book One).

The fifth and final section, “Thanatos’s Shadow” opens with “The Triumph of Death,” giving us Breughel as “a warning to be en garde” (p. 129). The poet mourns for the wife he has lost after their long marriage. His brief “Night Poem” speaks plainly of the slow march towards the invalid’s grave (p. 134). Simplicity strengthens these lines. Another very strong poem of mourning is “For Mahie” in which the poet tells of happier places and times to reach those “…tormented final years” (p. 137).

All the poems in this section move me; we all need to know what this poet has known:

“ ‘Stay,’ you want to say

with all the passion you can summon,

‘do not leave me now,’

yet the darkness has no answer

to a grieving with no cure” (p. 155).

After reading this book I feel a sincere gratitude to Philip Resnick for his knowledge of political history and most of all for being a poet who knows the worst and gives us compassion. “‘I have become my country,’ she declares,/ as Greece careens from crisis into crisis.” Here is the human sense of belonging that is different from nationalism or even patriotism. She knows it even as she dies.

*

Andrew Parkin was educated in Birmingham at school and then in the RAF Russian programme. After that he studied English at Cambridge and drama for a Ph.D. at Bristol. He emigrated to Canada and taught at UBC before going to the Chinese University of Hong Kong where, with the Chinese Canadian poet and translator Laurence Wong, he read at the Canadian Consulate and elsewhere on campuses. He retired to Paris and read for the Spring Poetry Festival there and in the “Poets Live” series, before returning to Vancouver with his French wife in 2015. He recently read with Jessica Li from his bilingual Star With a Thousand Moons (Victoria: Ekstasis) in the University of Regina and a few weeks later at York University, Ontario. Meanwhile he is completing a trilogy of novels about counter-terrorism.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#542 Classical, biblical, theoretical”

Comments are closed.