#454 The home children of Cowichan

Marjorie: Too Afraid To Cry. A Home Child Experience

by Patricia Skidmore

Toronto: Dundurn, 2012

$30.00 / 9781459703391

*

Marjorie: Her War Years. A British Home Child in Canada

by Patricia Skidmore

Toronto: Dundurn, 2018

$30.00 / 9781459741669

*

Both books reviewed by Sylvia Crooks

First published December 26, 2018

*

Heart-rending stories of children forcibly separated from their parents are all too numerous. We are daily made aware of the permanent scars left by residential schools, by governments falsely believing that they were acting in the best interests of the children and of society. We are shocked to learn that the practice lasted almost into the 21st century.

It is equally shocking is to learn that over a ninety-year period more than 100,000 poor British children were separated from their families and sent to Canada, to be trained to serve as farm labourers and domestic servants. They have come to be called Home Children. The program was meant “to secure the best opportunity for thousands of poor children who have little or no chance in the Mother Country.” It was also meant to help keep the colonies white. It is estimated that some ten percent of the Canadian population today is descended from these Home Children.

Marjorie Arnison was ten years old in 1937 when, without explanation, she was suddenly packed up and sent away from her family’s Tyneside home in northeastern England to the Prince of Wales Fairbridge Farm School at Cowichan Station, near Duncan on Vancouver Island, 6,000 miles away. Three of her confused and frightened siblings were sent away with her, clinging together as long as they could, but eventually separated from each other as well.

Marjorie’s daughter Patricia Skidmore tells the compelling story of Marjorie and the 11 members of the poor and vulnerable Arnison family who were victims of the child emigration program which had been carried out in Britain for over 300 years. As Skidmore writes, it is a story that centres on loss: “loss of country, loss of records, loss of family and of roots.”

The Arnison children were not slum or street kids. They played in the clean air and long, sandy beaches of Whitley Bay on the shores of the North Sea. Like 95 percent of the child emigrants sent overseas to the colonies and dominions, they were not orphans. But they were poor, often without warm clothing, shoes or sufficient food. In the early 1930s their father had moved to London to find employment, and the children stayed with their loving mother who did what she could for her children from the meagre funds her husband sent her only occasionally.

Immigration officials from the Child Emigration Society in 1937 identified the Arnison children as good candidates for the emigration program, and got permission from their father in London to take four of his children, with the agreement of the children’s mother and of the children themselves. The agreement of the mother and children seems not to have been sought, so ten-year-old Marjorie, twelve-year-old Joyce, eight-year-old Kenny and seven-year-old Audrey were parted from their mother and family home forever.

Years later, when Marjorie married and had a family of her own, she never revealed to her children that she had been a Home Child. She was angry at the loss of her family, and ashamed of what she considered rejection. She was silent because she had lost her roots. Her trauma crossed three generations: Marjorie’s own of course; her mother’s, Winnifred’s, who suffered “eternal distress” at the loss of her four children to Canada; and her daughter’s, the author’s, who grew up feeling shame and alienation from her mother who seemed to be harboring dark secrets from her past. Patricia Skidmore writes, “For years I had been ashamed of my mother. She was ashamed of herself. We were nobody. We didn’t belong. The shame was so heavy that, as a child, I felt it covering me, my head, my shoulders, even obscuring my vision…. My mother’s shame was my shame. Her rejection was my rejection.”

Finally, Skidmore decided to undertake a search for her mother’s past. She carried out pains-taking research to piece together her mother’s early life. She managed to awaken her mother’s memory which she had suppressed for so many years. The result is two books, based largely on the memories of Marjorie and her siblings, written in lively prose, and passionate in wanting to make the Arnison family’s trauma more widely known.

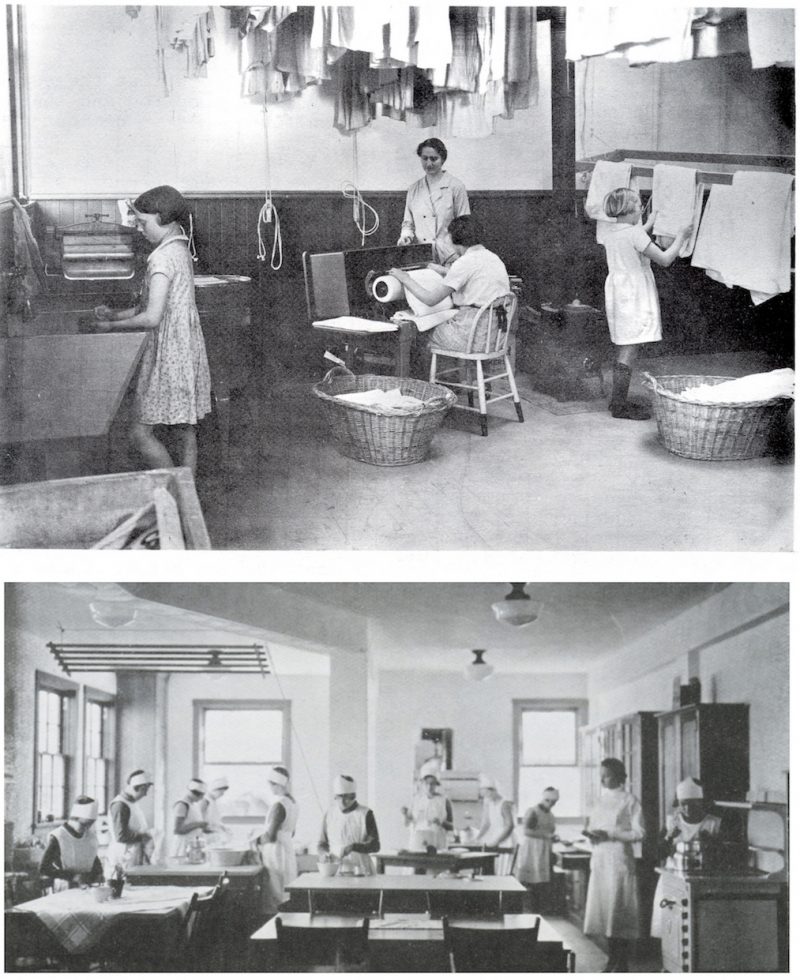

The first of the books, Marjorie Too Afraid to Cry: A Home Child Experience, was published in 2012. It tells the story of Marjorie’s journey with her three siblings, first to the Middlemore Emigration Home in Birmingham, to await and prepare for the journey abroad. It is Dickensian in its account of the callous treatment the children received there, like prisoners deserving of punishment, often cruel and without a shred of compassion.

After six months at Middlemore, Marjorie and her brother Kenny were suddenly sent off to London, then Liverpool and across the Atlantic to Canada. There was no chance to say goodbye to their two siblings left behind at Middlemore, Audrey, the youngest sister, because she was recovering from an illness, and Joyce, the protective oldest sister, considered too old for emigration. Audrey later joined Marjorie and Kenny at the Fairbridge Farm School but Joyce was made to stay at Middlemore, permanently separated from her siblings, until she was old enough to leave the Home for employment.

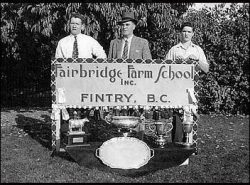

Marjorie Her War Years: A British Home Child in Canada, published in 2018, is a sequel to Too Afraid to Cry, focusing on the life of the children at the Fairbridge Farm School on Vancouver Island. The school was founded by South African Kingsley Fairbridge, whose intention was to provide impoverished British children with a healthy, rural environment, where they would be taught skills to prepare them for employment as farm workers and domestic servants. A Fairbridge school had been operating in Western Australia since 1912 when in 1935 the school was founded at Cowichan Bay, near Duncan. When it closed in 1949, 329 British children had passed through the school.

Marjorie and her brother Kenny arrived at the Fairbridge Farm School in September, 1937. Their younger sister Audrey arrived a year later. Marjorie spent five unhappy years at the school where she claimed she was “not brought up, but dragged up.”

The children were assigned in groups of about twelve to cottages on the large property, each of which had a “cottage mother,” most of whom Marjorie describes as “bitches from hell.” Skidmore writes in some detail of her mother’s memories of psychological and physical abuse: the lack of any affection, the undermining of self-worth, sadistic punishments for such transgressions as bedwetting.

The children were forced to lie to guests of the school about their miserable conditions, and letters to their parents in Britain were highly censored—only glowing reports were allowed or punishment followed. Evidence of sexual abuse of the children was made public in March, 2018 by the British Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse: Child Migration Programmes. Marjorie was aware of this abuse and, being ever protective of her younger siblings, she constantly warned them of it.

Skidmore details the daily life of the children at the school, made alive by imagined conversations, presumably based on Marjorie’s memories, and those of her brother and sister, whom Skidmore interviewed in later years. But one might question the need to invent the conversations and inner thoughts of the unfeeling cottage mothers, when their acts of cruelty and abuse have been documented by Marjorie and others who lived on the farm.

The one positive experience Marjorie enjoyed was the summer she spent at the Fairbridge Fintry Training Farm on Okanagan Lake, established to give the boys some instruction in working an orchard. Marjorie and another girl were sent to help in the kitchen. It was the first bit of freedom and kindness she experienced in her five years with Fairbridge.

Skidmore’s two books are an important contribution to efforts by British, Australian and Canadian governments to make the history of child emigration more widely recognized for the damage it did to so many British families. In 2009 the Australian prime minister made a public apology for the wrongs committed against the child migrants who were sent to Australia from the 1920s to the 1970s. British Prime Minister Gordon Brown in 2010 followed suit, and invited 65 of the migrants to London to hear his public apology on behalf of the British people.

Marjorie was among them, having finally consented to her daughter, Patricia Skidmore’s urging that she go. It was an emotional experience for Marjorie, and cemented the reconciliation of the three generations. Marjorie learned from meeting family members after so many years, that her late mother had grieved for her lost children to her last days. And Skidmore, through the uncovering of her mother’s history, had come to appreciate the courage and strength of character that had seen her mother through so many trials.

The Canadian government, too, does not escape the author’s anger and criticism, for the willing part it played as hosts of the child migration program. In February 2018 the Canadian House of Commons passed a bill proclaiming September 28 of each year British Home Child Day in Canada, recognizing the contribution the children have made to Canadian society, and “the hardships and stigmas that many of them endured.”

The research that Skidmore undertook is impressive. An extensive bibliography attests to many visits to archives and libraries, internet research and personal correspondence and interviews.

Marjorie’s story is enhanced by many photos of Marjorie and her siblings, both as children, and as adults when they met again, and scenes from Middlemore and Fairbridge. The first book has five appendices, including a transcript of Gordon Brown’s apology to British child migrants, and an extensive child migration timetable. Both books have a helpful index.

The two books are harrowing to read, but this story of one family’s experience helps us to better understand the destructive effects of the child migration program. They are also a testament to the human spirit, to resilience and reconciliation.

*

Sylvia Crooks is a retired faculty member of the UBC School of Library, Archival and Information Studies. She is the author of two books: Homefront & Battlefront: Nelson BC in World War II, and Names on a Cenotaph: Kootenay Lake Men in World War I.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster