#400 The useful people’s ranch

Ranch in the Slocan: A Biography of a Kootenay Farm, 1896-2017

by Cole Harris

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2018

$24.95 / 9781550178234

Reviewed by Daniel Clayton

*

The Bosun Ranch, in reality a farm just south of New Denver on Slocan Lake, has been in the Harris family since 1896. “The ranch has always been near the heart of my life, and more than anything else, I think, made me a historical geographer,” writes Cole Harris (born 1936), author of Ranch in the Slocan: A Biography of a Kootenay Farm, 1896-2017.

Ormsby reviewer Daniel Clayton considers the experience of dwelling on a Kootenay mountainside across five generations and reflects on the profound influence of the Bosun Ranch on Harris’s own writing about early Canada. — Ed.

*

Cole Harris is a Professor Emeritus at the University of British Columbia and an internationally renowned historical geographer. A plethora of distinguished books and essays — most notably The Historical Atlas of Canada (1987), The Resettlement of British Columbia (1997), Making Native Space (on the making of the reserve system in B.C.) (2003), and The Reluctant Land (on the geographical evolution of Canada before Confederation) (2008) — have brought him a string of awards and accolades, including the Canadian Historical Association’s Macdonald Prize (twice), the Srivastasa Prize for Excellence in Scholarly Publishing, the Order of Canada, and a fellowship of the Royal Society of Canada.

Cole Harris is a Professor Emeritus at the University of British Columbia and an internationally renowned historical geographer. A plethora of distinguished books and essays — most notably The Historical Atlas of Canada (1987), The Resettlement of British Columbia (1997), Making Native Space (on the making of the reserve system in B.C.) (2003), and The Reluctant Land (on the geographical evolution of Canada before Confederation) (2008) — have brought him a string of awards and accolades, including the Canadian Historical Association’s Macdonald Prize (twice), the Srivastasa Prize for Excellence in Scholarly Publishing, the Order of Canada, and a fellowship of the Royal Society of Canada.

In some respects his latest book, Ranch in the Slocan: A Biography of a Kootenay Farm, 1896-2017, is unlike anything he has written before. It is a local story about a particular place rather than a geographical synthesis of larger-scale questions of colonial society and space in North America, which has been Harris’s forte. It is a story that ventures out of the Canadian/ colonial past, where Harris’s work has been focused, and into the present. It is a lovingly observed, and in places candid, portrait of the Harris family’s Bosun Ranch in the Kootenays that is based on personal memory and family records (diaries, journals and correspondence, chiefly from Harris’s grandfather, father and uncle, but also a broader body of family reminiscences), and comes with 91 illustrations (most of them family photographs).

The book’s thirteen chapters dwell on the life of a well-watered terrace — the pick of the farmland, but an “extreme example” of the “bounded space” awaiting B.C. immigrants – overlooking the town of New Denver in the Slocan Valley — a remote, scenic and tranquil corner of British Columbia to which settlers, prospectors, hippies, nature-lovers and tourists have long been drawn (p. 3). Harris provides an affectionate chronicle of the lives, gifts and foibles of the five generations of his family that have revolved around this resplendent spot, rather than a study that is drawn from the more detached interpretative vantage point and reckoning of the historical geographer.

Harris has spent most of his career painting particular people and places on to panoramic landscapes of social and geographical change, and exploring how different — colonial, native, Canadian and provincial, coastal and interior, and rural and urban “voices” — have been situated within them. Ranch in the Slocan has been written foremost for his family, and with a changing of the guard afoot in its 120-year association with this patch of land. After some years of uncertainty surrounding the ranch’s future, which stem, we are told, from a magnanimous but ineffectual will left by Harris’s grandfather in 1951, that future has now been secured (both legally and spiritually) for the fourth and fifth generations, for whom ten of the chapters lie beyond personal memory (pp. 173, 264).

The story begins in Calne, Wiltshire (UK), with Harris’s grandfather, Joseph (Joe), an energetic rugby-playing youth from an industrial-liberal-evangelical family that had made its money pioneering new methods of curing bacon and ham. While Harris skips over the matter, in England the Harris family name is irrevocably associated with its bacon brand. As the great food writer Alan Davidson explains in his entry for “bacon” in The Oxford Companion to Food (his entries for “high tea,” “noodles,” “toast” and “trifle” are legendary):

The first large-scale bacon-curing business was set up in the 1770s by John Harris of Calne, Wiltshire…. Until this time pigs for London’s bacon had been driven long distances on foot before being killed there, which exhausted them and spoiled the meat. Harris realized that it would be more practical to make the bacon where the pigs were and send that to London. The standard commercial method of curing bacon is known as the ‘Wiltshire cure’… A Wiltshire side is a large piece of meat, and is divided up for various purposes. The shoulder yields the cheapest bacon; the most valued is back and streaky bacon.[1]

Working initially out of a butcher’s shop, a Harris bacon factory was established in 1888, employing over 2000 people at its peak, and the Harris “Wiltshire cure” remains one of the UK’s most recognisable meat trademarks and export brands.

This spirit of entrepreneurship lay at the heart of the British Industrial Revolution, and it was one closely associated with philanthropy and liberal ideals of utility and social reform. Deemed to have no head for business by his father, Joe Harris was despatched to Guelph Agricultural College in Ontario to make himself “useful,” and at a time when “the colonies” were seen as a safety valve not only for “undesirables” from the lower rungs of the social ladder but also for “wayward” youth farther up, many of whom were keen to escape suffocating class conventions and use their privilege to explore the world and reinvent themselves.

The late nineteenth century was the heyday of empire, and Joe was well positioned to benefit from the opportunities it presented. At Guelph he fell in with the son of a prominent Anglo-Irish colonial family from B.C., the Musgraves, and was invited to summer with them on Salt Spring Island. He mixed easily with B.C.’s colonial gentry (and took to their leisurely life of teas, tennis, boating and nature walks), but was no snob. He travelled back and forth between Ontario and B.C., and Calne and Canada, a number of times before seeing B.C. as his destiny, and used family money to establish a farm on marshy, stumpy ground in the Cowichan Valley with the help of an “unlikely crew” of friends and misfits, including a Royal Navy deserter, “the Bosun,” with whom he formed a close bond (p. 20).

Joe ventured to the Slocan Valley in 1896 looking for land upon the recommendation of a Bohemian couple he had met in the Cowichan Valley who knew George Bernard Shaw and Beatrice and Sidney Webb (who helped to found the Fabian Society; Beatrice Webb was one of the founders of the London School of Economics). He bought 270 acres of land but figured that less than 30 acres of it “was really fit for cultivation” (p. 40). “Such a lot of possibilities and no certainty anywhere,” he reflected in a 1943 retrospective on his coming to this distant edge of B.C., which he was encouraged to write by his daughter Heather (pp. 38, 26). Ranch in the Slocan is essentially about this observation: about possibility and uncertainty; about the excitements of place and deceptions of space associated with the experience of dwelling on a bench on a Kootenay mountainside.

However, the stories bound up with this observation also spiral away from this book and into many of the broader questions that Cole Harris has pursued during his distinguished career. In other words, while Ranch in the Slocan is a family history and local study, it is also a poignant way into many of Harris’s wider takes on B.C., Canada and North America. “The ranch has always been near the heart of my life, and more than anything else, I think, made me a historical geographer,” he wrote in the Introduction to The Resettlement of British Columbia: “Most of the essays in this volume probably revolve around it.”[2]

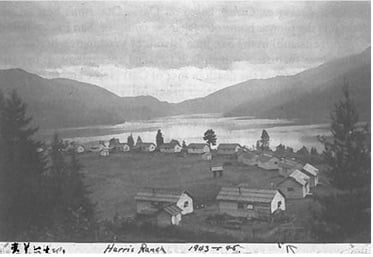

Harris brings this rotation — what there is in his family background that explains what he has done in his “larger” books — full circle in Ranch in the Slocan, albeit with some limits. For example, while Native-newcomer relations have formed a large part of what Harris has written about, Joe Harris encountered barely any Native people, especially in the Slocan Valley. The Native population there had been decimated by the smallpox epidemic of 1862. But had there been Native people around, Harris surmises, his grandfather “would have treated them with kindness and respect,” as he did the Second World War Japanese internees who were camped on the Bosun Ranch (which Joe leased to the Federal Government for $50 per month) (pp. 6, 152). As it was, Joe Harris thought he had come to an empty as well as “beautiful land and with it the opportunity to start again and right past wrongs” — the wrongs, in his mind, of a “decadent society” (p. 65).

Joe built a rudimentary cabin and subsequently wrapped a substantial ranch house around it, chiefly, Harris surmises, to please his well-travelled Scottish wife, Margaret, who he had met on an Atlantic liner in 1899, “who was accustomed to some comfort,” and who imagined (was perhaps told) she was coming to a well apportioned colonial estate (p. 53). He ploughed all the English money he had into his farm and home, putting down an orchard, raising a family, and cherishing his life and opportunity, even when the family money started to dry up and the orchard failed. There was no ready market for his produce, even when frontier commercial speculation and industry, in the form of a silver-lead-zinc mine, operated (intermittently) on Harris between 1898 and the 1930s.

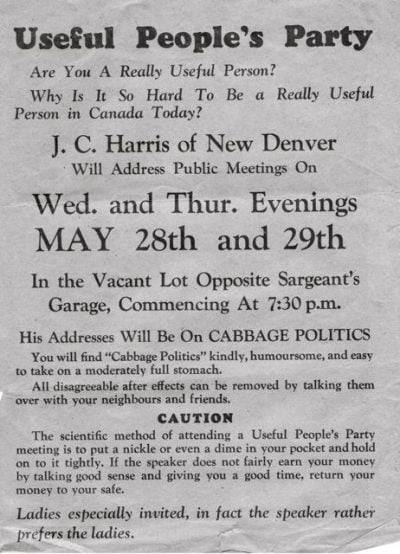

Yet there was no remorse on Joe’s part about the fact that the ranch “produced work, not product,” as Harris summarises the situation, and as life went on the place became “less a failed commercial farm than a locus of thought and argument about social change” (pp. 111, 114). Moreover, outlooks that hailed from the world Joe had left behind, including some strong attachments to Fabian (socialist) and evangelical ideals of cooperation, comradeship and responsibility (all of which circled around the question of what counted as a “useful” life and contribution to society) became reworked in the Slocan, and in some idiosyncratic ways.

Joe’s politics spawned speeches, pamphlets, and a “Useful People’s Party.” As Harris reflects on one of his grandfather’s tracts, on “cabbage politics,” “Just as there are many varieties of cabbages, so there were many varieties of humans. Whatever the variety, the value of cabbages, as of humans, depended on their having good sound heads and tender hearts” (p. 126). But included in this political vision (metaphor) were the weeds that infested Joe’s cabbage patch, and he likened them, Harris continues, to “the misplaced individuals that infest society” (p. 126). Harris thus points not just to the quirkiness of some his grandfather’s ideas, but also to the dangers that lurked in them — about society being comprised of “useful” and “useless” people, about those cabbages and weeds, for instance.

Overall, the point is that lives were being lived and ideas were being formulated within the peculiarities of a farm and were slowly veering away from their English/ metropolitan reference points. They were becoming “radically decontextualized,” Harris writes, and recontextualized along particular lines: the ranch “was not, like most pioneer settlements in Canada, a product of a stark encounter between poor immigrants and forest along the northern margin of North American agriculture. At hand, certainly, was a forest and pressing agricultural boundary, but also an English upper-middle-class background, and associated money, education, and expectations” (p. 112).

Many of these expectations remained notional and as time went by the split between these excitements of place (dreams and prospects) and deceptions of space (disappointments and failures) became more pronounced. The part of the Harris family that stayed on the ranch after Joe died (Harris’s Uncle Sandy and his wife Mollie) had a place they adored but a farm that was barely viable from a commercial point of view. They worked hard and lived frugally, and in the long run only managed to keep on top of the place with a chance windfall of around $75,000 from the sale of a power facility that Sandy had operated to the BC Power Commission in 1956.

“The value of the Ranch is something that money doesn’t enter into,” Sandy wrote to his daughter Nancy and son-in-law John Anderson in 1967, and at a moment when folk from the American counterculture movement were starting to identify the region as a destination for their own personal and spiritual (if often self-interested) quests. “The Ranch is a way of life & it’s very good when one looks around at the other ways of life and sees how much unrest and uncertainty there is,” Sandy continued (p. 191). He loved nature, loved it by knowing the land on which he lived intimately, and treated many of the wild animals on the ranch (especially deer, and a grouse he named Chunky) as pets. Nature, he judged, was more giving than human nature, and here, Harris says, is further proof that “Being in a different place has consequences” (p. 204).

In 1960s North America some of the deceptions of space that had made life on the Bosun Ranch hard for Sandy and his family were turned back into something more comforting, as Harris notes:

In a new society recomposing itself at a margin of empire where places were being created and abandoned and flux was commonly at hand, Sandy’s ranch was unusually rooted. There was no opportunity in immigrant British Columbia to live, in situ, with a long past stretching back through the generations, as so often there had been, and in many places still was, throughout western Europe, but Sandy had pushed that connection with his particular place almost as far as his immigrant society allowed (p. 204).

Elements of this connection imbued the hippy artists and crafts folk who came to the valley and ranch during the 1970s. They helped to knock down the dilapidated old ranch house (Sandy’s family lived in a cabin away from the main house that his Scottish uncle had built in 1902), and restore Joe’s original homestead (sparser cabin), which was rediscovered within (p. 180). In Harris’s estimation, this “meeting of the American counterculture and the old ranch house tended to reinvigorate the social critique embedded in the ranch,” and the labour and craft involved in this project rekindled the family’s marriage to “a place where lives might be lived creatively, close to the land, and apart from the mainstream” (p. 229).

Family histories are not easy things to write. There are difficulties of one sort or another in most families, and Harris does not paper over tensions within his. Such difficulties often involve questions of prerogative and property, and the awkward personal relationships that become entangled with them. With questions of entitlement left somewhat in the air by Joe’s will, strains between “those who lived on the ranch, and those who came for the summer” (including Harris’s father and mother, Dick and Ellen, who worked in Vancouver) grew and festered (pp. 173, 230).

This recent history of the ranch could easily have been the spoiler that brooked a rather different — Dickensian, dystopian — story, and with John, who latterly had de facto control over the running of the estate, on the verge of selling most of the land to real estate developers when the financial crash of 2008 hit and this speculative venture went up in smoke. Harris laments this scene but stays upbeat, reflecting in the Epilogue: “Perhaps land itself has no memory, though I sometimes think it does, but we who loved the ranch remembered, and were appalled” (by the prospect of this sale) (p. 258).

And so it is, you will have gathered by now, that a book which is about a particular family and place is also a meditation on where many of Harris’s core — and influential – ideas and interests come from. Let me now reflect a little on these edges of Ranch in the Slocan.

*

Harris has long pursued the question of what happens to people when they move out of one context and settle in another (particularly far-away and unfamiliar places), and has argued that social change in colonial settler societies came about through geographical change. Societies and identities changed through encounters with new lands and environments. The life-ways forged by early European settlers in North America had as much to do with the new geographical circumstances in which they found themselves as they did with the ideas and practices they brought from Europe, he maintains.

Readers will find in Ranch in the Slocan some rich family material with which to think about how, as Harris has sought to show, European societies became “simplified” (“pared away” and “recalibrated” are other favourite expressions of his) as they settled down in new lands and in new social combinations. European social hierarchies became flattened, and the consequences of colonisation were for most part dire for Indigenous people. Emigrants tended to view the new lands to which they were venturing in carte blanche terms, and enticing and unfettered spaces of opportunity, and mostly viewed the aboriginal inhabitants they met as obstacles to their ambitions. And when things did not go immigrants’ way, Native people were often made scapegoats.

This book captures Harris’s wider interest in how processes of social and geographic change were fuelled by both idealism and disappointment. Vast and inviting lands often turned out to be more limited and less habitable than they had appeared in the mind’s eye or on the map. Space was deceiving. French and British immigrants who settled around the Great Lakes and along the Saint Lawrence Valley did not get far north without running into the Canadian Shield, fierce winters, the back-breaking work of clearing land, and a struggle for survival. This is one of the core messages in The Historical Atlas of Canada.

In B.C., traders, colonists and prospectors ran into mountain ranges and steep ravines, Native people who had settled much of the most accessible and fruitful land, and on whose land lay lucrative forest and mineral reserves (not least gold), and agricultural land that proved to be considerably less fecund than it seemed at first blush. In fairly short order, settlers like Joe Harris discovered that they had come to a region that was part of a geographically bounded and regionally differentiated country.

Harris has also been concerned with how this dialectic of hope and despair was more acute, and often precarious, in the countryside than in the towns. The basic equation between land and labour was reversed in many of Europe’s settler colonies: labour there was scare rather than abundant (and often underemployed) as it was in Europe, whereas land in the colonies was plentiful rather than meagre and almost entirely owned by a small land-owning class as it was “back home.” Harris has argued that while more trappings of European class structures endured in the towns of colonial North America than in the countryside, in both town and countryside European hierarchies were prone to being chiselled away. Without a longer European past — centuries of custom and convention — cushioning and fettering individual fortunes, rural settlers in regions like B.C. grappled in more immediate and visceral ways with both the dream of being able to make one’s own way in the world and attain freedom and satisfaction through hard work, and the spectre of illusory riches and the threat of falling on hard times.

Such ideas have spawned a great deal of debate, and Harris has cultivated a historical-geographical perspective on the colonial evolution of North America that vies with sociological perspectives that tend to subordinate questions of land, environment and space to the meeting of “frontiers” of thought and experience (economic, social and political models and experiments) and the “fragments” (ethnic, religious, linguistic and agrarian sub-cultures, and class, family and village enclaves) of European society.[3]

One might question how long, by the mid-nineteenth century, the European past was for many who emigrated to B.C. They lived through the turbulence and dislocation of the Industrial Revolution: a time marked by mass uprooting and migration, and new forms of social mobility (as with the bacon-producing Harris family); by what Marxist scholars have described as a profoundly disorienting bout of “time-space compression” (a rapid rearrangement in how time and space were experienced, principally in the forms of factory work, wage-labour, time discipline, machine technology, urban squalor and consumerism); and by the increasing accessibility of empire to growing numbers of Europeans through travel, settlement and work, and which, along with mounting metropolitan awareness of colonial conditions — and importantly of Native resistance to empire — conspired to both “produce” European culture (spur its arts and sciences, and infuse its political and popular culture, and attitudes of dominance and superiority) and foster an existential crisis within it.[4] Harris himself has pondered some of these issues and they complicate how one might understand the “simplification” of Europe in B.C. or nineteenth-century Canada.[5]

Even so, Ranch in the Slocan is a vibrant meditation on why family histories matter in places like B.C., and of the pleasures and perils in recognising that such stories rub, sometimes brusquely, against canons of social history and projects of geographical synthesis like Harris’s, wherein individual actors and particular settings and vignettes are treated as exemplars of wider processes, positions and trends. Harris has toyed with this question of individual and collective, and local and non-local, meaning for his entire academic life, and this book shows that his question of “simplification” is as much personal as it is professional.

How does where one comes from, and where one settles, shape understanding both of that “where” and of “who” one is? Is genealogy more important, or more fraught, in a place like B.C., where immigrant family histories are forked in two directions: first, in the way they can be dated and resonate in quite precise ways (from 1896 in this book), compared with many “Old World” family histories that melt into the mists of time (albeit, as a large postcolonial literature now reveals, with elements of this mist scattered across oceans and empires, undermining any clear sense of, for example, “the English” or “Europe”); and second, in the sense that awareness of the youthfulness of B.C.’s non-native society comes with an anxious radiance (an added need for that society to tell itself what it is) because there is also a Native presence that does stretch back into the mists of time, and as Ranajit Guha famously observed in a wider imperial register, this presence made empire profoundly “uncanny” for it protagonists, for while empire seeks “to make a home of its territory” it will always struggle to do so because it “rules by a state [governments, colonists and ideologies of “us” and “them”] which does not arise out of the society of the subject population but is imposed on it by an alien force.”[6]

Inevitably given its remit, Ranch in the Slocan takes a selective path through such matters. However, Harris’s meditation comes with a spiritual edge that has a wider and worthy reach. As I read the book, it is about what philosophers since ancient times have called “the good life”. This expression appears in the title of an essay in The Resettlement of British Columbia — “Industry and the Good Life Around Idaho Peak,” which deals with the Bosun Ranch, and, as Harris puts it in this current book, with “two very different economies, values, and ways of life” represented by the farm and the Bosun mine (p. 69). The idea of the good life infuses the writing of his grandfather, father and uncle, and his own work. It is a buoyant idea, especially in our current dark times, and has seemingly kept the Harris family going through thick and thin.

For Harris the good life is an existential idea with profoundly geographical moorings. There are means of living and arts of living, he suggests. The former need to be measured in relation to the latter, and both need to be gauged in relation to where and how well one dwells. The good life revolves around how to find opportunity with what one has or finds where one ends up, and the responsibility one has for that bequest. Duty — or, more exactly, the duty to nurture afforded opportunity — forms a large part of the biography of the Bosun Ranch; but on Harris’s account so does fun and inquisitiveness.

Harris is by no means the only geographer to venture down this sort of path. It is ensconced within a broader tradition of “humanistic geography” which came to the fore within the discipline of geography during the 1970s, and which he helped to forge. It can be found in the idea of what one of his former colleagues, Yi-Fu Tuan, has called “romantic geography:” a geography that is not simply about the adoration of place or love of landscape, but, more fully, about the desire to find splendour and comfort in those places by questioning familiarity and complacency, embracing wonder, diversity and change, and recognising that there is a fine line between having (sharing, caring for, and experimenting with) and holding (seized and sequestering) place. Tuan’s romantic geography is a rich geography of attachments and reveries, but one that can lapse into a less attractive — defensive and inward-looking — “blood and soil” geography of loyalties and rivalries over turf, identity and nation.[7]

As with Tuan, Harris’s outlook on life, and his own hopeful version of this romantic geography, is infused with a sense of both its preciousness and precariousness: of how difficult this geography can be to make and sustain, and how place can become bound up with adversity, disaffection, suffering and loss. While Native history does not figure in this book, Harris’s Making Native Space grapples with this scene of precarity and his narrative there is troubled by how colonists came to see B.C. as a glorious new start in a place that they thought they could cast in their own image, and by pushing Native people out of the picture in the process. Of course Native homes, families and communities would suffer from the imposition of a reserve system that took away their land and the possibility of a good life. And Native people would, of course, struggle over the very thing, land, that was central to this possibility and to home and family. This is the flip side to the geography that Harris cherishes in this book, and one that he knows well.

However, his general message is one of hope, and for him hope resounds even in the ranch’s connection with one of the darkest moments in Canadian history: Japanese internment. While he observes that this amounted to a “failure of white British Columbians to come to terms with diversity,” and acknowledges that there was a local geography of Japanese-white segregation in New Denver, he uses Japanese as well as family testimony (this is the most fully footnoted chapter of the book) to suggest that “something else, something creative… was stirring on the Harris Ranch, and probably in other camps where Japanese and other Canadians mixed” (p. 172).

It is this creation and harbouring of the good life that energises Harris’s narrative in Ranch in the Slocan, and this vitality goes a long way, I think, to explaining the great pride and pleasure that he and his wife Muriel have taken over the decades in inviting people (myself and members of my family included) to visit and stay at the Bosun Ranch. This energy is captured in Harris’s detailed descriptions of the changing living arrangements, furnishings and inhabitants of the farm; and in his lengthy quotations from family letters and journals (especially in chapters 2, 4 ,5, 7 and 10).

His philosophy of the good life can be found in the detail of the book: in the diary entries, in the photographs, in the family stories and anecdotes, in Sandy’s affection for his pet grouse, in Harris’s mother’s creation of a love nest (cabin) in a corner of the ranch away from the main house, and in Harris’s own reflections on how “the ranch produced well-lived lives” (p. 262). He represents his family as lucky to have had the opportunities the ranch has afforded to live generous, caring and creative lives, and tells us that, in the end, this good life has been worked at and was never simply given, in spite of his grandfather’s money and privilege.

I will end on my own philosophical note, and finally come to my title. For me, Ranch in the Slocan opens up what the French geographer Michel Lussault has termed “the experience of dwelling” — a term he uses to evoke a basic plank of human existence (if it is still possible to talk in such a fundamental way). He writes:

Environments open and arrange themselves for and through the geographies which make them exist and that they permit. Latent before action gives them substance, they only exist in terms of potentiality and their configuration depends on possibility and constraint…. This perennial environment, which surrounds and welcomes action, and with its circumstantial spreading of life lines… is a context put into space by the very play of dwelling (by those who dwell and use objects and materials to dwell), and, by this very fact, it passes through us as much as it surrounds us, it is as much inside us as it is outside us.[8]

Harris’s great skill in this book is to show how the Bosun Ranch passes through the Harris family as much as it surrounds it, and how it is inside much else that Harris has written. To my mind, the experience of dwelling has never been far from what Cole Harris has sought to understand, and this concern is by no means confined to either rural dwelling or the North American past. It is a basic part of human existence and has a profound stake in who we are and what and where we want to be. The idea of dwelling is integral to the handle he has on the world, and it is explored in this book with great tenderness and wisdom.

The fourth and fifth generations of the Harris family will treasure the book their father and grandfather has written for them, and anyone who has visited the Bosun Ranch (or found themselves in the outdoor bath pictured on p. 232!) will find a little bit of themselves in this biography, and understand a little of what Lussault means by the “spreading of life lines” through “the experience of dwelling.”

*

Dan Clayton teaches Geography at the University of St Andrews, recently described by Michael Palin (upon receiving his honorary degree in Geography) as “the most distinguished and venerable university on the northeast coast of Fife.” Dan looks rather well in the picture (in the circumstances). It is the only one of him on the internet (that he knows of!). He has degrees from Cambridge and UBC, and is the author of Islands of Truth: The Imperial Fashioning of Vancouver Island (UBC Press, 2000), and a wide array of essays, book chapters and reviews. He continues to work, sporadically and at a distance, on the northwest coast — look out for “Placing Joseph Banks in the North Pacific: Assignment, agency and assemblage,” Journal of Maritime History — and is on the Editorial Board of BC Studies. He is also co-editor of The Scottish Geographical Journal (high quality submissions in an area of geography welcome!), and has just completed (co-authored) Impure and Worldly Geography: Pierre Gourou and Tropicality (Routledge, 2019). His PhD was supervised by Cole Harris, and one of his current projects, on the Vietnam War, was inspired, in part, by the ‘nam vets he knew during his Vancouver days.

*

[1] Alan Davidson, The Oxford Companion to Food (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 49-50.

[2] Cole Harris, The Resettlement of British Columbia (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1997), p. xx.

[3] See most recently, and for this phraseology, James Belich, Replenishing the Earth: The Settler Revolution and the Rise of the Anglo-World, 1783-1939 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 69 and passim.

[4] On time-space compression see David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989). On this fin-de-siècle existential crisis of self and empire, see Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993) — incidentally, Said first addressed this question in a talk he gave at UBC’s Institute of Asian Research in 1991.

[5] Compare Cole Harris, “The simplification of Europe overseas” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 67, no. 4 (1977): pp. 469-483; Cole Harris, “Power, modernity and historical geography,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 81, no. 4 (1991); pp. 671-683; and Cole Harris, “How did colonialism dispossess: Comments from an edge of empire,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 94, n. 1 (2004): pp. 165-182.

[6] Ranajit Guha, “Not at home in empire,” Critical Inquiry 23, no. 3 (1997): pp. 482-493, at p. 482.

[7] Yi-Fu Tuan, Romantic Geography: In Search of the Sublime Landscape (Maddison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014).

[8] Michel Lussault, « L’expérience de l’habitation », Annales de géographie, 704, no. 4, (2015): pp. 406-423, at pp. 410-11.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#400 The useful people’s ranch”

Comments are closed.