#41 Haggerty’s pre-Hippie Vancouver

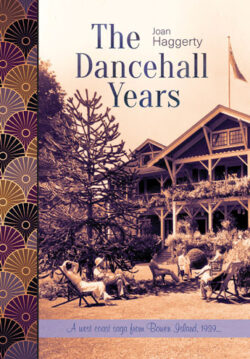

The Dancehall Years

by Joan Haggerty

Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue Publishing, 2016

$20.00 / 9781896949543

Reviewed by Tom Shandel

First published November 11, 2016

*

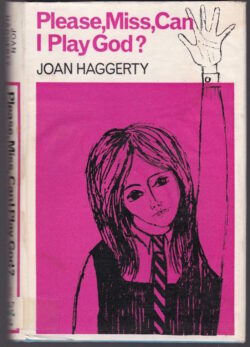

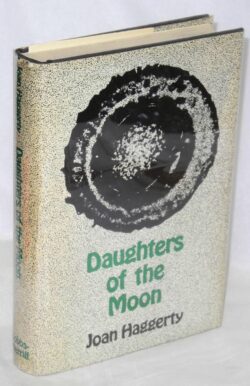

Joan Haggerty has always been in a vanguard of very few. Her first book, Please, Miss, Can I Play God (Methuen, 1966), was based on her teaching drama to inner-London kids. Daughters of the Moon (Bobbs-Merrill, 1971) her debut novel, presented a struggle for self-determination via the power of childbirth and the independent female. It was followed by The Invitation: A Memoir of Family Love and Reconciliation (Douglas & McIntyre, 1994), another story of motherhood transcending shibboleths.

Joan Haggerty has always been in a vanguard of very few. Her first book, Please, Miss, Can I Play God (Methuen, 1966), was based on her teaching drama to inner-London kids. Daughters of the Moon (Bobbs-Merrill, 1971) her debut novel, presented a struggle for self-determination via the power of childbirth and the independent female. It was followed by The Invitation: A Memoir of Family Love and Reconciliation (Douglas & McIntyre, 1994), another story of motherhood transcending shibboleths.

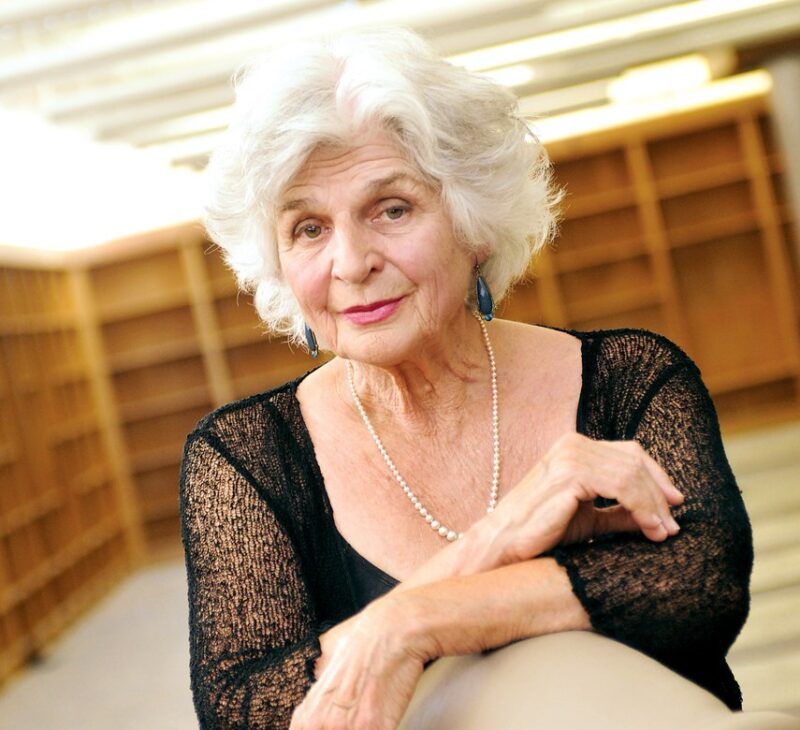

I’ve lost touch with Joan Haggerty over the last twenty-five years or so, but her new book brings back to mind so much of what made our friendship work for me. In The Dancehall Years, she is as fearless as ever in revealing her guts with shameless honesty.

The Dancehall Years fills an important gap. Not many books reveal a street-level depiction of Vancouver in the 1940s, ’50s, ’60s and ’70s before it became “world class” and corporate.

Vancouver during those decades was a place for intolerance of racial and religious differences, unquestioning acceptance of the status quo, unarguable patriotism, the sacred belief in manners and financial self-reliance. This “small-c” conservativism of middle class Canada prompted many of us to renovate ourselves—Joan Haggerty included.

For Joan, this prevailing conservatism was found in leafy south Dunbar, Southlands, Magee High School and summers on Bowen Island. Although The Dancehall Years is set in Joan’s own history and memory for its authenticity and accurate detail, it soars beyond memoir when it brings important contemporary values to bear on the idyllic world on Bowen Island.

A young, central character, Gwen, must come to grips with the Japanese internment during the Second World War, inciting her to forge her independence from the constraints of her upbringing. Inter-racial marriage and childbirth out of wedlock are the touchstones for her emotional and critical responses.

From 1939 onwards, we follow Gwen’s progress as she matures and experience Bowen Island through her eyes.

Bowen Island in the 1940s was to Vancouver’s middle class what Georgian Bay is for Ontarians. Taking the Union Steamship from Vancouver harbour to Bowen was a couple of hours’ journey, far enough away that many people stayed over in rentals or brought their tent. Bowen’s small community of locals serviced the annual invasion of summer visitors.

The not-forgotten struggles of The Depression were lightened by escapes to the soft summer days on Bowen. At the heart of Bowen social life was the local hotel and the dance hall, the centre of adult pleasure where Gwen and the other kids gathered in the early evenings to stare in wonder through the windows at the fairyland world where children were not allowed.

Then came Pearl Harbor in 1941. Due to patriotic racism, the Japanese Canadians, even if they were born in B.C., were forced to be exiled inland, even from quiet and comfortable Bowen, and properties were confiscated. In The Dancehall Years, as a youngster, Gwen watches uncomprehendingly the removal of a respected Bowen family integral to the life of the island.

Most of us know about the internment story through the writings of Joy Kogawa and David Suzuki, or through documentaries such as one made by Linda Ohama. As someone who has lived most of my life on the West Coast, I thought I knew all about the Japanese Canadian internment story, but this rendering has made a deeper impression on me.

As an old Japanese Canadian couple is dispossessed of their property, the indifference of Bowen Islanders to not only former friends but important suppliers of food from their gardens is shocking. This easy bigotry is handled brilliantly, particularly within the intimacies of Gwen’s own home with her Dad.

But Haggerty takes it much further. Not only is there the reality of inter-racial relationships in 1941, but a child is born, and in a monstrous attempt to “protect” both the young unwed mother and the family’s reputation, Aunt Isabel is told the baby died at birth. This family skeleton haunts her book, and Gwen, as she grows up, comes to understand the horrific lie which middle-class sensibilities found necessary.

Along the way, The Dancehall Years also offers a multi-faceted representation of coastal life: an appreciation of tides, of commercial fishing, of UBC and “higher learning,” of synchronized swimming, and of being a single Mom in an age when pregnancy out of marriage was something to hide. Same sex relationships were taboo and families still valued their pristine reputations higher than children’s originality and possibilities.

Few novels resonate so well with the zeitgeist of my formative years here since the 1950s. We were a post-Beatnik, pre-Hippie generation—not necessarily a lost generation but surely a mostly ignored one.

*

Tom Shandel is a journalist and filmmaker who knew Joan Haggerty when they were wannabe actors in the Sixties, taking classes at UBC. Before he became a prodigious documentary filmmaker, they both appeared in Elmer Rice’s Dream Girl for the UBC Players Club. Tom Shandel lives at Cowichan Bay.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#41 Haggerty’s pre-Hippie Vancouver”

Comments are closed.