#26 A whale named Moby Doll

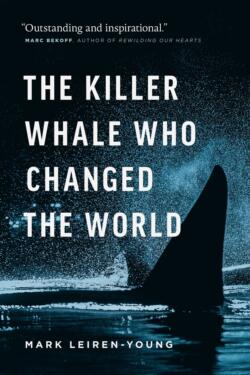

The Killer Whale Who Changed the World

by Mark Leiren-Young

Vancouver: Greystone Books with the David Suzuki Institute, 2016

$29.95 / 9781771641937

Reviewed by Daniel Francis

First published Oct. 17, 2016

*

My most memorable encounter with a killer whale occurred in 1987. Newly returned home after sixteen years living in eastern Canada, I thought it would be a good idea to take my Ottawa-born children on an outdoor adventure to acclimatize them to their new coastal habitat. What better than whale-watching at Telegraph Cove on Vancouver Island? It was late afternoon and the captain of the boat was losing hope that we would see any whales when a message came over the radio that a pod had been spotted in a channel not far away. Soon they were breeching and spy-hopping all around us. Welcome back to British Columbia!

My most memorable encounter with a killer whale occurred in 1987. Newly returned home after sixteen years living in eastern Canada, I thought it would be a good idea to take my Ottawa-born children on an outdoor adventure to acclimatize them to their new coastal habitat. What better than whale-watching at Telegraph Cove on Vancouver Island? It was late afternoon and the captain of the boat was losing hope that we would see any whales when a message came over the radio that a pod had been spotted in a channel not far away. Soon they were breeching and spy-hopping all around us. Welcome back to British Columbia!

Thirty years earlier I would have been teaching my children to fear orcinus orca as a man-eating monster of the deep. Killer whales were once among the most reviled animals on the planet, targeted for sport and slaughtered to make animal food. Fishermen shot at them with rifles, and the government installed a machine gun overlooking their migration route to drive them away from local salmon grounds. Murray Newman, the first director of the Vancouver Aquarium, remarked that they were considered “the marine world’s Public Enemy Number One.” Yet here we were admiring their sociability and apparent intelligence, shooting photographs instead of bullets. The whales had become the poster animal for BC’s coastal environment. What happened?

The Killer Whale Who Changed the World

What happened, according to Mark Leiren-Young in his engrossing new book, The Killer Whale Who Changed the World, was a whale named Moby Doll. In the summer of 1964 a whaling expedition mounted by the Vancouver Aquarium managed to capture a young killer whale off the south end of Saturna Island. Intending to kill a specimen to use as a model for a hanging sculpture in the Aquarium’s foyer, the hunters instead “hooked” their quarry with a non-fatal harpoon shot through the back. Not sure what to do, they called in Newman and his colleague, the neuroscientist-politician Pat McGeer, who made the decision to keep the whale alive.

The hunters led Moby Doll, as he became known, behind their boat across the Salish Sea “like a dog on a leash” to a dry dock on the North Vancouver waterfront. For weeks the animal refused to eat and McGeer used a long pole with a hypodermic syringe at the end to inject vitamins and antibiotics. The whale attracted an enormous amount of attention; it was as if a creature had arrived from another planet (which in a sense it had). The public was allowed to visit the dry dock and the press kept a daily watch. Eventually Moby Doll was moved to a purpose-built enclosure at Jericho, which is where he died less than three months after his capture. The city went into mourning. “It was like a death in the family,” said McGeer.

Moby Doll’s time in captivity was brief but it was a transformative event in the history of the BC coast. It marked the beginning of a remarkable change in public perception and scientific understanding. This is the real subject of Leiren-Young’s book and the reason why he argues that Moby Doll “changed the world.” Able to get close to an orca for the first time, people began to recognize that it was a peaceable, intelligent animal, not a fearsome monster. The downside of this discovery was that a market opened up for captive whales. Around the world, marine parks and sideshows wanted their own Moby. The coastal waters of British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest turned into a hunting ground for killer whales. Leiren-Young calculates that by 1973 almost fifty of the animals were captured here and at least a dozen died in the process. The value of a killer whale soared to $400,000 in today’s money.

In one sense, then, Moby Doll was a disaster for the orcas. On the other hand, the hunt that he inspired led scientists to question the sustainability of unregulated live capture. In 1971 a Nanaimo-based federal scientist named Michael Bigg came up with a plan to count the local orca population. The results were shocking. Everyone had assumed there were thousands of whales; instead the census showed there were only a few hundred. This in turn led to regulations prohibiting capture and protecting the whales. Meanwhile, Bigg and other scientists carried out research that taught us much about the behaviour of the whales: their social organization, their intelligence, their “language,” their life cycle. There is much still to learn, but most of what we do know is thanks to Bigg and his colleagues and successors here on the West Coast.

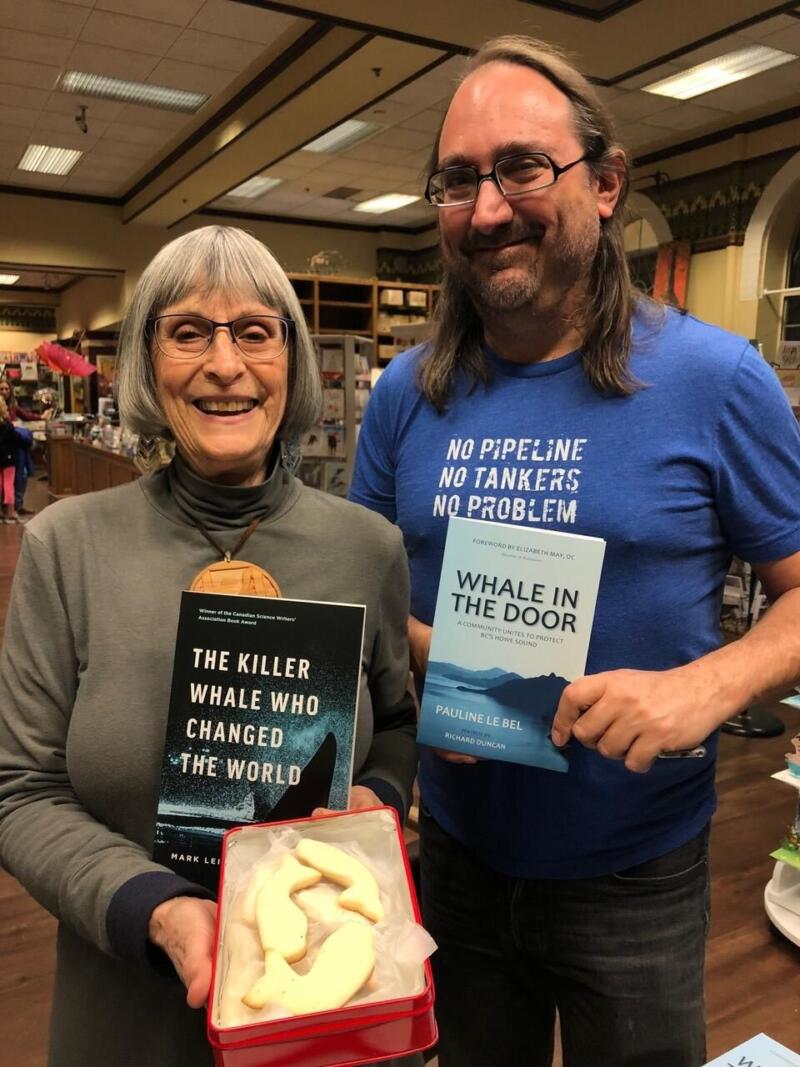

Leiren-Young tells this story with gusto. He seems to have talked to everyone involved with Moby and with subsequent orca research. The book comes with some interesting photographs but shame on the publisher for not including an index.

It is evident from Leiren-Young’s account that while Moby Doll may have changed our world, he did not change the world of the orcas all that much. Humans have stopped killing them but there are other threats. In some countries, live capture continues. Locally, the decline in salmon stocks threatens their food supply. Whale-watchers sometimes harass the animals by chasing them “like a pack of hound dogs.” Noise pollution from boat traffic interferes with their ability to communicate with each other and perhaps identify prey. Fuel spills have the potential to contaminate their habitat.

Moby Doll was the beginning of a profound transformation in the way that humans thought about whales but Leiren-Young’s book tells us that there is much still to learn about the orca and a long way to go before they are safe in their coastal environment.

*

Daniel Francis edited the Encyclopedia of British Columbia (Harbour, 2000), having previously worked as an editor for Mel Hurtig’s Encyclopedia of Canada. Francis has also written the definitive biography of Louis Denison Taylor, which received the City of Vancouver Book Award in 2004. He recently received the Governor General’s History Award for Popular Media / The Pierre Berton Award at Rideau Hall in Ottawa. For more information about Francis and his thirty books, visit his blog.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “#26 A whale named Moby Doll”

Comments are closed.