Discovering the explored

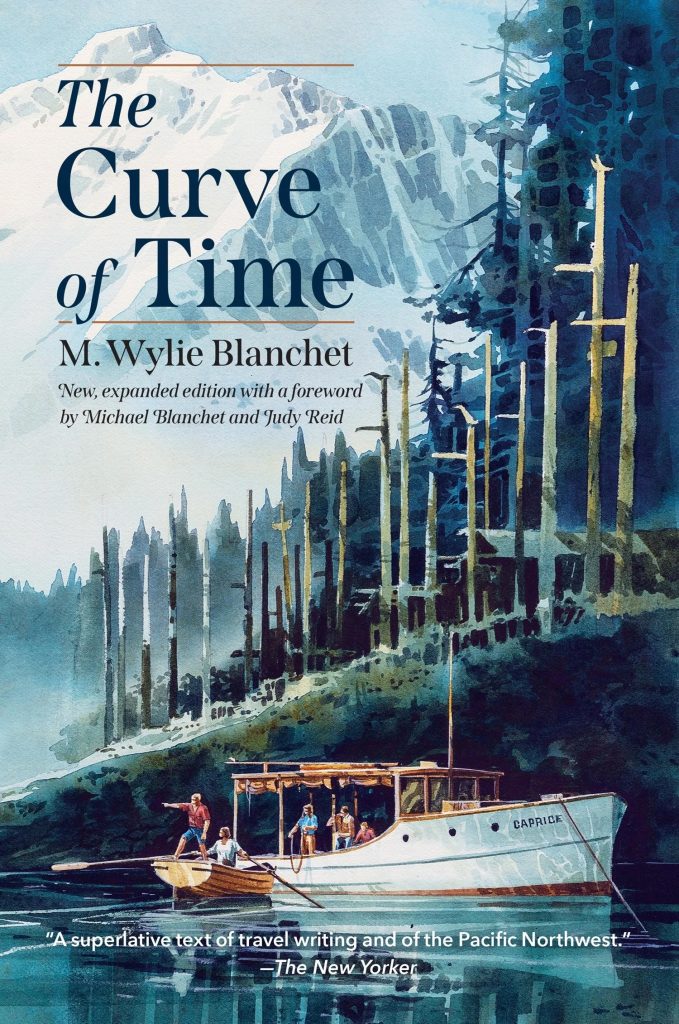

The Curve of Time: New, Expanded Edition

by M. Wylie Blanchet (forewords by Michael Blanchet and Judy Reid, preface by Howard White, essay by Edith Iglauer)

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2024

$19.95 / 9781990776786

Reviewed by Matthew Downey

*

It has been nearly a century since Muriel “Capi” Blanchet, as a widowed young mother of five, first began sailing the coastal waters of British Columbia with her children. Her classic book of memoirs about those experiences The Curve of Time is now over 60 years old and has seen 11 editions in print. Its latest expanded edition, which includes a foreword from Blanchard’s grandchildren, the author’s own personal correspondence, supplemental chapters not yet published in book form, and numerous illustrative photographs and maps throughout, greatly enhances the book’s historical context while maintaining its unique personal characteristics. With its mix of transcendent personal philosophising and unique environmental culturalization, Blanchet’s writing remains highly relevant to the 21st century British Columbian as an historical text and enduring influence on British Columbian identity.

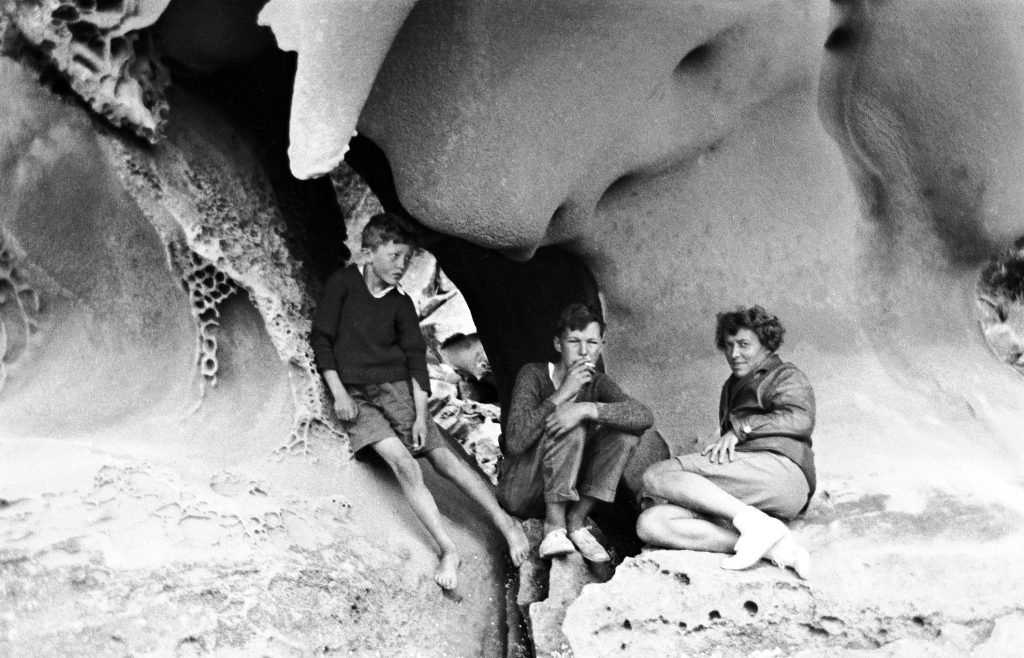

One learns a lot about Capi Blanchet through reading Curve of Time. Her own personal experience is paramount, and every other character remembered throughout the narrative, even her own children, slip in and out of focus with the scenery. The entire story takes the form of waves of memory from throughout the course of about a decade of experiences traversing the inner passage between Vancouver Island and the mountainous inlets of mainland British Columbia. As the reader rambles around Capi’s point of view, learning more about her natural, philosophical, and practical interests, and gaining insight into her emotional attachments, one is yet struck with a sense of mystery about her. The biographical sketches and other supplementary additions featured in this expanded edition provide a great appreciation of Capi’s personal intrigue. Having been born a High Anglican in Quebec near the end of the 19th century, Capi married young and moved with her husband and small children to North Saanich in 1922. After only four years on the West Coast, Mr. Blanchet disappeared in a boating accident; that boat, the Caprice, having been recovered unlike its pilot, was the same small yacht that the Blanchet crew would trust with taking them on their many annual summer trips up the coast through the years. This irony colours Curve of Time, though the husband’s absence is only cryptically referenced in brief moments of reflection. It casts a dark grey tone on the events of the book – both those of dangerous excitement and comforting relief – in a way that perfectly matches the rainy-drenched coastal geography, contributing to its intrinsically British Columbian identity and its place in establishing the mythical culture of this province.

The name of Curve of Time makes reference to the philosophies of J.W Dunne, which root a belief in precognitive dreaming in a theory of time that states how waking consciousness creates an illusion of progress, and only in sleep can we see glimpses of the oneness of past, present, and future. Dunne’s theories, as relayed through the writings of Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck, provide a thematic inspiration for Blanchet’s writing, as well as a subject of reflection throughout the narrative. On several occasions Blanchet seeks to validate the ability for some dreams to predict personal experiences. Wildlife encounters and the weather are glimpsed in dreams, only to later be encountered by the Caprice’s crew.

Moreover, the book’s very structure embodies its author’s Dunnean disposition. Set over the course of a decade, Blanchet skips to-and-fro between the years, never giving much note of the particular time besides the months and seasons. Each new chapter takes the form of a conversational memory, with even the Blanchet children fading in and out of narrative relevance with little intro or exit. The Curve of Time is a variety of disparate memories stitched together, sacrificing chronological accuracy for geographical detail (although even its place-descriptions remain unreliable). This impression of an endless yet incongruous summer is suited to the clouded coast of BC, in which August can unpredictably feel like November, July like September, September like August, and June like March.

Blanchet’s contemplation of the illusory nature of the present seeps into her description of space. Just as the past and future live alongside one another in the dream-state, isolated wilderness and human community coexist in Blanchet’s description of the coast. The wilds are anything but empty, and not untouched by human activity. Curve of Time puts on display coastal British Columbia’s own version of the wild west, in which homesteaders and transients alike seek to make their marks in a land untapped by European industry. However, unlike the more familiar American wild west narrative, in which individual industriousness contributes to an inevitable march towards violent and assimilatory progress, Curve of Time features a deceptively cyclical vision of the ongoing settlement of Canada’s west coast. Characters encountered and befriended by the Caprice’s crew, usually men, include Norwegians, Californians, and French Canadians. While attempts are made at logging, hunting, fishing, and planting by these 20th century pioneers, in Blanchet’s description these actions are more akin to the futile and monkish behaviour of hermits than the spearhead of colonization. The settlements and homes described nearly always come across as temporary, destined to die out with its inhabitants. Like characters in a Tolkien story, in the midst of the most unapproachable locations the Caprice’s crew come across surprisingly refined and comfortable cottages complete with inviting hearths, intriguing libraries, and productive orchards. However, Blanchet describes a world of decay rather than development; if her writing is infused with colonial assumptions, it lacks colonial sympathies associated with geographical consumption. The Blanchets explore the aftermath of European civilization’s entrance into the region, and as Curve of Time’s reference and mirrors Captain Vancouver’s exploratory travels through the coastal inlets in search of a Northwest Passage it acknowledges a sense of mastery of the territory while maintaining its mystery. The coastal passageways had been thoroughly recorded, but they beg constant re-exploration; it had been settled but is doomed to be constantly re-settled.

Blanchet’s experience of the rural coast as contradictory realm of static progress and decay is the context in which the Indigenous peoples exist in her view. In her writing they are an ephemeral presence, treated with a mystic respect yet unacknowledged as a practical presence. A striking curiosity inspires Capi to seek out the winter villages of First Nations up the coast as places of particular interest, and she is reverential towards their ability to instinctually navigate the tidal torrents that surge through the Discovery Islands. Simultaneously, however, the Blanchet crew betray a certain disregard of the Indigenous peoples’ present cultural rights. While casually breaking into longhouses left abandoned for the season Capi and her children gain unfettered access to the personal and ancestral belongings of its sometime inhabitants. Artefacts are grasped from the beaches, only to be revealed as the former contents of decaying coffins placed in the trees according to the First Nations’ traditional customs. While mostly positive feelings towards Indigenous people are expressed, Blanchet’s writing portrays them as an unfamiliar people. The Indigenous villages feel like a part of the limbo that is the natural world to Blanchet, distinguished apart from the peopled elements. In this way Blanchet is thoroughly of her time, despite her attempts to communicate timelessness; her assumption of Indigenous decline matches her era, but the way the First Nations and their proud history are tied to her natural appreciation nonetheless contributes to Curve of Time’s relevance as a cornerstone of British Columbian cultural heritage.

Curve of Time amplifies an imagined identity of British Columbia, one in which an implausible combination of wildness and civility are highlighted to great measure. Its relevance as an historical text is tied to the way in which it embodies the inalienable characteristics associated with Pacific Canada – the meaning behind the images that we put on our postcards, licence plates, and TV commercials. Blanchet champions the idea of British Columbia as a wilderness that is not untouched but nonetheless untamed; it is infiltrated by the subtleties and odiousness of human society but overpowering in its resolute aloofness.

One gets a sense that Blanchet is unusually prepared and capable within her environment, with her exceptional mechanical skills and a decisive disposition, and yet one can regardless never be prepared enough to deal with the challenges of the unconquerable natural world. For all the consultations of charts, stars, and local knowledge, intuition is oftentimes the more reliable advisor to Capi. Ultimately, the Caprice and her crew are dependent on nature’s will; they learn from and utilize tidal charts but acknowledge that the key is just waiting and listening for the right time. Illustrating Capi’s desire for natural faith, she fondly references a story of how the Indigenous people could supposedly rely on the goodwill of their gods for the right moment to pass through tidal rapids. Mastering the mysteries of British Columbia’s wilderness is not about imposing one’s intellectual force on its problems but rather is made possible through the maintenance of social resilience. The ideal of BC inspired throughout Blanchet is society within nature, accepting its pre-eminence while paving around it; this is an ideal many British Columbians pretend to pursue to this day.

The enduring cultural resonance of Blanchet’s writings, and its corresponding consistent appeal to readers, rests on its establishment of a metaphysical underpinning for the particular character of British Columbia’s coastal culture. Strange and sometimes contradictory feelings attach people to this place – pride and fear, awe and indifference, exploration and homeliness. An eeriness pervades the Curve of Time – the sort of dreamlike eeriness that might feel familiar to those from coastal BC. The same natural features that make such endearing tourist postcards can kill you with a change in the wind – the austere mountains can produce an outburst of avalanching ice; the marine passageways criss-crossing the coast can inhale a boat within a whirlpool or rip its hull with a hidden reef. For those homesteaders Blanchet encounters the dramatic scenery can inspire the artful humility of natural coexistence, or its imposing heights can drive one to claustrophobic mania. Vancouver Island and the coast is an uncanny place; there is an ever-present stink of death in the mist and rain that feeds the rainforests, and one sometimes imagines its acidic soil could decompose a pickup truck. But there is a civilized comfort to accepting that eeriness and resigning oneself to live within it, and that is what Blanchet embodies alongside the other character she meets hellbent on living along the coast. Curve of Time represents a significant part of coastal British Columbia’s cultural heritage – Blanchet’s writing epitomises the provincial stereotype as the home of aspirant eccentrics, philosophically ponderous lumberjacks, and hopeless romantics seeking to carve out a small, domesticated presence in the dense rainforest. Blanchet’s representation of British Columbia, in which urban settlement is an exception to the cultural status quo, still resonates today; the fact that waterproof hiking boots and raincoats remain the height of Vancouver fashion speaks to the way that even some of the most metropolitan British Columbians identify with the same wilderness Capi Blanchet contemplated all those decades ago.

*

Matthew Vernon Downey is an independent writer and researcher based out of Victoria, B.C.. He has degrees from UVic (BA hons) and the London School of Economics (MSc) [Editor’s note: Matthew Downey has also reviewed books by Jonathan Manthorpe, Robert Amos, Alan R. Warren, Gregor Craigie, Robert Crossland, and Donna (Yoshitake) Wuest with Joe W. Gardner for The British Columbia Review. He has also contributed an essay on the subject of Amor de Cosmos.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

4 comments on “Discovering the explored”

Capi Blanchet was my neighbour in the 1950s and 60s…when I was a child living on Curteis Point. What an extraordinary woman! I admired and feared her, as she could look fierce, with a blunt or laconic manner in speaking. I only saw her at Halloween, when I would knock on her door for candy. When Richard Mackie of the BC Review (then Ormsby Review) saw my comments about Capi in my autobiography, he asked to publish the story. Titled The Spider Hunters, my story described the forest and ocean culture that Capi was part of, along with publisher Gray Campbell, and other assorted war heroes hiding out in the woods. I regret that I was too young to appreciate these folk whose colourful post-war culture shaped my childhood. — Thanks, Lee Reid

Thanks for sharing this, Lee, as well as providing the link to your excellent contribution to the Review, The Spider Hunters. What a wonderful connection to have made, with “Capi.” It’s often when we reach adulthood when we realize the connections, and perhaps questions, it would have been ideal to ask of those figures we grew up with, isn’t it?

One of my favourite books. Utter magic. I recently completed a novel that follows in its beautiful shadow…

Excellent Theresa! I’m looking forward to reading it.