‘Being in relationship with place’

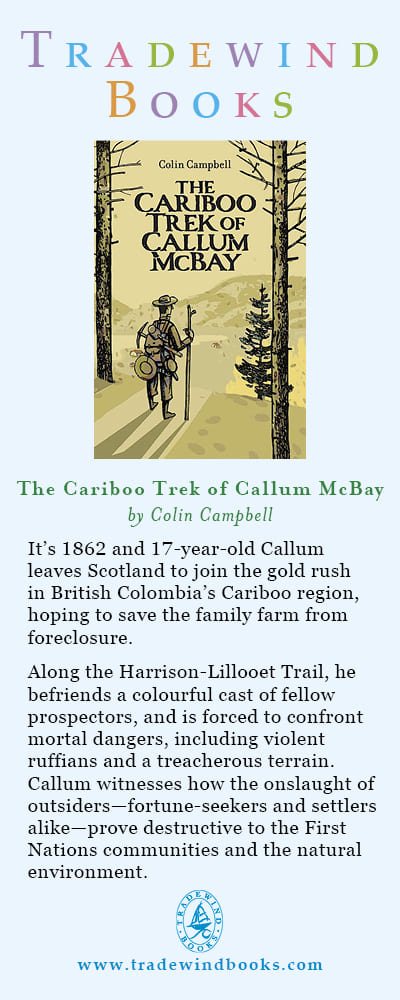

Held By The Land: A Guide to Indigenous Plants for Wellness

by Leigh Joseph

New York: Wellfleet Press (a Quarto imprint), 2023

$24.99 / 9781577152941

Held by the Land Deck: 45 Ways to Use Indigenous Plants for Healing and Nourishment

by Leigh Joseph

New York: Wellfleet Press (a Quarto imprint), 2024

$19.99 / 9781577154440

Reviewed by Kenneth Favrholdt

*

Held By The Land (Wa Ch’ích’istway Ta Temíxw) is a unique and beautiful publication describing the cultural importance of trees, shrubs, flowering herbs, ferns, horsetails lichens, and seaweeds to be found here. Author Leigh Joseph is an Indigenous ethnobotanist who was compelled to write the book for her children, community, and her home territory, Skwxwu7mesh (Squamish, British Columbia). The book’s title, Joseph says, means “being offered what you may need in a particular time.” Plants provide that.

Joseph’s ancestral name Styawat, meaning “the wind that blows away the clouds and brings the sun,” was bestowed by her late great-uncle Chester Thomas from Snuneymuxw (Nanaimo First Nation) where she spent much time as a child. She completed her Masters of Science in Ethnobotany at the University of Victoria (2012) under the guidance of Dr. Nancy Turner, Dr. Trevor Lantz, and members of her Skwxwú7mesh family and community.

Joseph’s book is more than a field guide to plants. It reflects her philosophy and love of nature. She states, “The book is meant to be an intersection between my lived experience as an Indigenous woman, my training in Western science, and my cultural journey toward identity…. I intend this book to be a helpful companion and to support cultivating respectful ways of being in relationship with place and with plants.”

In its 191 pages, Joseph has combined her deep knowledge of plants, how plants can be harvested (either “growing in the wild or planted in a garden setting”), and their uses (gifts is a better expression). Plants, as living things, are considered relatives among the Skwxwu7mesh. “This belief in plants as relations frames the entire relationship with culturally important plants and the ecological habitats in which they grow.” This philosophical approach permeates the book and Joseph’s outlook.

The first chapter explores the relationships with plants and the land from a cultural and personal context. Chapter 2 explores the teachings that plants carry and “what we can learn when we are more attuned to plants and the environments in which they are found growing.” Chapter 3 looks at building your own apothecary at home. Chapter 4 is about harvesting; Chapter 5 introduces steps for developing ones very own botanical and land-based mindfulness practices. The next section of the book goes into detail about 44 culturally important plants that grow in the Squamish territory. Including eight tree types; nineteen shrubs such as devil’s club, labrador tea, sala, soapberry, and wild rose; and thirteen flowering shrubs, including camas, cow parsnip; stinging nettle, and yarrow. The last section of plants incudes lichen, horsetail, fern, and red laver, an alga.

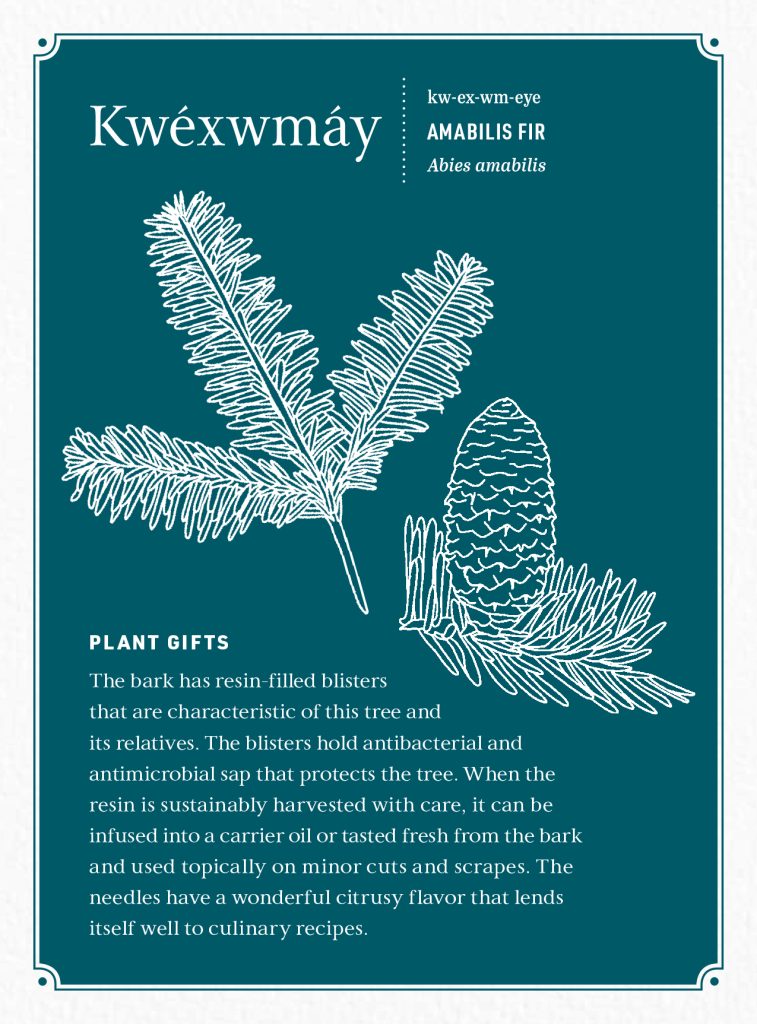

Although Joseph’s research focuses on the plants of the Squamish area, many of the plants can be found in many parts of British Columbia. In her descriptions of each species Joseph speaks of building relationships, habitat, botanical description, sustainable harvesting and timing, and plant gifts, including how the plants can be used medicinally and in culinary recipes. Joseph states, “The ranges of most of the plants included here are vast and will cover many different Indigenous territories as well as ecological zones.” For example, she states, “Kwéxwmáy (Amabilis fir) is found from southwestern British Columbia except Haida Gwaii, down to the Cascade Mountains in Washington and Oregon and to Northern California.” The plants are named in the Squamish language translated by Myia Antoine and Sarah Jeffreys.

The book concludes with Joseph’s reflections on what she has learned (and what her readers can take from her practice), followed by a botanical glossary, an overview of plant oil used for skincare, and some additional recipes to those described earlier in the book. In her acknowledgements, Joseph thanks her Squamish ancestors, her children, grandparents, mother and father, siblings, auntie, and many others. The references and index provide a key to other resources.

While there are earlier books that describe Indigenous plants such as her mentor Nancy Turner’s Food Plants of Coastal First Peoples (1995) and Jim Pojar and Andy MacKinnon’s Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast (1994), Joseph’s book, in a way, is a prequel to others.

Everyone should learn more about the natural environment and the plants that are nourished by the land. Says Joseph, “Plants and the land have agency. They have their own spirits, names, interconnections, needs and power.” At a time when many Indigenous groups are making a renewed connection with the land, this guide supports that initiative and provides an example of the work that is being undertaken.

At a time when decolonization is important to the revitalization of Indigenous peoples’ knowledge and culture, Joseph’s book breaks new ground in the way plants are described, utilized – and respected.

*

Held By The Land Deck is an accompanying resource to the book, consisting of an attractive set of 4 ½ x 6 inch cards and a small guidebook. Joseph describes how to plan a foraging trip, how to set up a home apothecary (a collection of plant ingredients with topical and internal health benefits), how to identify 44 culturally significant plants of the Squamish region and beyond, how to harvest plants, and how to develop a respectful relationship with them. A 45th card shows illustrations of different leaf and inflorescence types.

The plants appearing on the 45 profile cards are written in Skwxwu7mesh (Squamish), a phonetic pronunciation, English, and their scientific (Latin) name. The cards are colour-coded for trees, shrubs, flowering herbs and ferns, horsetails, lichens, and seaweeds. Joseph provides information about poisonous plants and sustainable harvesting and wildlife. Leigh has stated, “the cards are a great portable option to bring on the trail with you or even use them as flash cards to practice the Squamish plant names.” The plants are shown in drawings, not by photographs, highlighting their outlines and texture. I would protect the cards and guidebook in a waterproof ziplock bag — the only caution not mentioned.

The guidebook describes how to use the cards, including cautions about poisonous plants, and advice about harvesting. There is a short botanical glossary, and an appendix of “Recipes for Inner and Outer Health” and “Building Relationships with the Land.”

Leigh Joseph, it should be mentioned, is also an entrepreneur who has brought together her knowledge of Indigenous science and self-care, producing skincare products that incorporate sustainably harvested and sourced botanicals. The company she founded, Skwálwen Botanicals, “draws on ancestral teachings that are connected to traditional plants and the land in her research.”

*

Kenneth Favrholdt is a freelance writer, historical geographer, and museologist with a BA and MA (Geography, UBC), a teaching certificate (SFU), and certificates as a museum curator. He spent ten years at the Kamloops Museum & Archives, five at the Secwépemc Museum and Heritage Park, four at the Osoyoos Museum, and he is now Archivist of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc. He has written extensively on local history in Kamloops This Week, the former Kamloops Daily News, the Claresholm Local Press, and other community papers. Ken has also written book reviews for BC Studies and articles for BC History, Canadian Cowboy Country Magazine, Cartographica, Cartouche, and MUSE (magazine of the Canadian Museums Association). He taught geography courses at Thompson Rivers University and edited the Canadian Encyclopedia, geography textbooks, and a commemorative history for the Town of Oliver and Osoyoos Indian Band. Ken has undertaken research for several Interior First Nations and is now working on books on the fur trade of Kamloops and the gold rush journal of John Clapperton, a Nicola Valley pioneer and Caribooite. He lives in Kamloops. [Editor’s note: Kenneth Favrholdt has recently reviewed books by James R. Gibson, Patrick Brode, Taiaiake Alfred, Wayne McCrory, Michael Hood & Tom Jenkins, and Rueben George with Michael Simpson for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster