Empire’s remote rural estate outpost

Between Heaven and Balmoral: A History of Cary Castle, British Columbia’s First Government House 1860-1899

by Robert Ratcliffe Taylor

Victoria: FriesenPress, 2024

$17.49 / 9781039184534

Reviewed by Martin Segger

*

This is Robert Ratcliffe Taylor’s third architectural biography. His previous two were The Spencer Mansion: A House, A Home and an Art Gallery and The Birdcages: British Columbia First Legislative Buildings 1859-1857. In terms of its topic, the book nestles between two previous volumes, Peter Cotton’s architectural exploration of the two Cary Castles that preceded the present 1958 Government House, Vice Regal Mansions of British Columbia, and Government House: The Ceremonial Home of All British Columbians by Rosemary Neering and Tony Owen which primarily focuses on the current house.

In the first two of eleven chapters, Taylor recounts the sad tale of George Cary, a brilliant and frenetic barrister, politician, and entrepreneur who imagined himself as a country gentleman squiring over a rural estate on the outskirts of this outpost of the Empire. Arriving in Victoria in 1859, Cary combined the roles of Attorney General for the colonies of both British Columbia and Vancouver Island, along with those of barrister, land investor, and member of the House of Assembly. In the latter role, he acted as de facto finance minister and wrote several bills, including ones establishing the land registration and taxation regimes, a voting bill and a companies registrar for the new colony. While doing so he acquired extensive speculative land holdings around Victoria. Alas, Cary’s career was both meteoric and short. His ambitious political efforts and development schemes devolved into financial insolvency, accusations of fraud, and finally “certified insanity.” In 1865, his friends financed a ticket back to England, where, mad as a hatter, he died the next year.

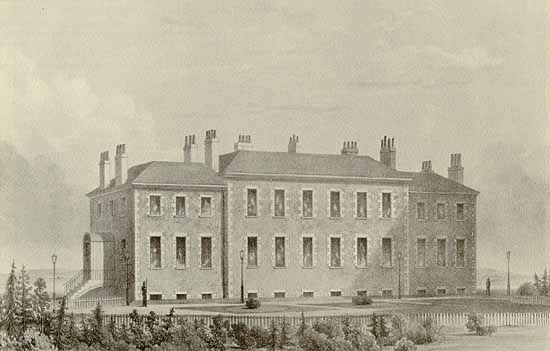

The precarity of the young colony’s finances and dithering by the Assembly required several feats of procedural legerdemain. The new Governor, Arthur Kennedy, obtained a loan from the Bank of British North America, bought the house along with a lease of some of James Douglas’s farmlands, then flipped them to the colonial government. Alas, Kennedy was to discover he’d bought “a pig in a poke.” Sitting abandoned for two years after Cary’s bankruptcy the house was mouldering wreck with numerous roof leaks and other deficiencies. Kennedy commissioned the new-to-Victoria, but probably most professional team of architects in the town, John Wright and George Saunders, to draw up plans for renovation and expansion of the castle. Alas, cheapness, combined with a lack of competence in the construction industry and shoddy building materials, resulted in leaks, mould, drafts, and even fires that would plague Kennedy and subsequent vice-regal inhabitants throughout the structure’s 35-year life.

Wright and Saunders’ ambitious plans, which incorporated parts of the existing turreted stone building, were never completed. However, over the ensuing years what gradually emerged was an eclectic combination of Victorian cottage, colonial bungalow, and Gothic ruin.

Taylor devotes chapter four to a virtual tour of the house as it appeared between 1875 and 1882 following earlier additions. This is skillful detective work as photographic records are haphazard and a complete set of as-built drawings has not survived. By then we find a U-shaped plan with various appendages, which unfold like a minor country house. Formal spaces such as a large ballroom, drawing room, dining room, billiard room, entrance hall, and garden verandahs are punctuated by numerous fireplaces and chimneys. (The latter contributing to its ultimate demise.) A second floor accommodated five formal bedrooms, dressing rooms, water closets, and some servant’s accommodations. Photographs reveal sumptuous furnishings and elaborate fixtures including cut-glass chandeliers. This image Taylor pieces together from contemporary paintings, photographs, auction inventories and, ultimately, the insurance claim after the 1899 fire.

A rich social history fills in the story. Taylor takes us through the tenancies of the vice-regal representatives whose serial occupation set a high standard for the cultural life of Victoria in those years. Alongside this was a constant battle with both the British and local bureaucracies regarding gubernatorial stipends, expense accounts, repairs, and upkeep. The sorry state of the house might have contributed to Governor Seymour’s ill health and finally death while on tour to Bella Coola in 1866.

A major feature of the house was its location and adjacent gardens. Governor General Lord Lansdowne noted, during an 1885 visit, that he would love to pitch his tent in spot on the Rockland landscape which by that time it combined formal gardens, natural woodland acreage, and of course, the dramatic views and vistas across Douglas’s Fairfield farmlands to the snow-capped Olympic Mountains outlining the fringe of the Juan de Fuca Straits. Battling inadequate water until hook-up to the City mains in the late 1880s, a series of talented head gardeners managed to maintain extensive lawns along with patterned floral beds, the effect recalling English landscape gardens of the day. Lady Aberdeen commented on their “very gay appearance.” Lt. Gov. Richards was a passionate amateur gardener and was often mistaken by visitors as the hired man, much to his amusement. The gardens provided a fitting backdrop for the endless round of fetes, receptions, balls, verandah teas, “musicales,” at-homes and games of croquet that constituted the active social life of Victoria’s polite society.

The ceremonial and social life of Cary Castle is detailed in the book’s final chapters. These and enlivened by a rich account in Chapter Ten under the title “Working at Cary Castle.” Here it is interesting to learn of the lives and rituals of the supporting cast, from Chinese cooks to personal secretaries. Often the latter came as part of the vice-regal entourage, sometimes a close relative. Maids, messengers, housekeepers, coachmen, and gardeners all had roles to play, proverbially “keeping the show on the road.”

Throughout this compact volume, Taylor provides the reader with a rich context, recounting how the lives of this class of colonials constantly referenced their British roots whether it was in choices of furnishings, social rituals, class attitudes, and even how they imagined the social roles and situation of the house itself. In this little changed from Cary, its builder and first resident, to the last Vice Regals, the McInnes family.

The book closes with a dramatic account of Lt. Gov. Robert McInnes and his wife Martha narrowly escaping the disastrous fire that finally put an end to all this on May 18, 1899, as Taylor recounts, the last and ultimately most devastating of 9 recorded fires in the building. The Vancouver Province lamented the loss of “one of the most historic and as well as one of the oldest residential buildings of B.C.” Cary Castle had witnessed a turbulent political and social history that included a colourful Attorney General, Governors of British North America’s western-most colonies, the first Governor of Vancouver Island, then the combined colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia, and early Lieutenant Governors of the post-confederation province of British Columbia.

But in terms of British Colonial history the house remains an anomaly. This is somewhat explained by situating it within the penchant for castle building facilitate by the new-found wealth of Victoria’s aspiring gentry class. Such crenellated piles which dominated the early rural landscape of Victoria included Charles Pooley’s “Fernhill,” Senator MacDonald’s 1877 “Armadale” in James Bay, and ultimately the 1887 “Craigdarroch Castle,” coal baron Robert Dunsmuir’s castellated monument which upstaged Cary Castle both in scale and its nearby hilltop location atop the Rockland escarpment. Castle building continued into the Edwardian era. Cary Castle II held onto its predecessor’s name when Francis Rattenbury and Samuel Maclure completed their arts-and-craft style evocation of the castle form to serve as the replacement government house in 1903. As late as 1914, architect Henry Griffith completed “Spencer Castle” (he actually called it “Fort Garry”) for himself atop a craggy bluff on upper Cook Street. But the ultimate expression of the style had to await Hatley Park, James Dunsmuir’s full-on version of the English castellated country house completed in 1908 with 650 acres of manicured gardens and woodland landscape on the road to Sooke, now home to Royal Roads University.

Situating the symbolism of Cary Castle within the expansive country house building of the mid-Victorian period, including the ambitious efforts of the royal family at Balmoral, Aberdeenshire, or Osborne on the Isle of Wight, is a topic that could be further developed.

As Taylor notes, Cary Castle did not stand up to other Canadian vice-regal accommodations such as Halifax, St. John’s, or Quebec City. To a professional civil servant like Governor Musgrave, whose colonial service reads like a tour of the far-flung regions of the Empire including South Australia, Jamaica, Queensland, and Newfoundland, Victoria’s rambling cottage would have been a bit of a let-down. But it should be understood the colony of British Columbia was established at a radical intersection British imperial enterprise. Under Disraeli’s reform government ,the mid-nineteenth century witnessed the disestablishment of an Empire dominated by the great national joint-stock corporations, the British East India Company, and the Hudson’s Bay Company being illustrative examples.

Governor’s residences in the age of the corporate (by royal warrant) empire freighted heavy symbolism linking these enterprises with the sovereignty of the Crown reinforced by the firepower of the British Imperial Navy. The rule of the East India Company effectively ended in the chaos of the 1857/8 Sepoy mutiny and Parliament had dissolved the EIC by 1874. The Hudson’s Bay Company turned over its colonial settlement franchise to the Crown with the establishment of British Columbia and Vancouver Island colonies in 1858. By 1864, a representative government had been established in Victoria. The HBC had already begun ceding its land holdings to the Dominion of Canada, as British colonial policies now focused on an Enlightenment-inspired vision of a networked Empire consisting of self-governing Dominions. Outsized neo-classical monuments were not part of this vision; neither was money made available to build them. So diminutive Cary Castle, more public garden than building, comfortably fit the new order – although interesting in that, when it came time for the Province to replace the smouldering ruin with a new Government House, Cary Castle II, both in size of its monumental presence and a home-grown architectural style, would make a bold statement about the new Province’s aspirations as a major player in the Canadian confederation.

Three appendices contain anecdotal side notes on the main text. Detailed footnotes follow.

Taylor provides us with a good and engaging read which benefits from his attention to detail and the variety of perspectives on the topic at hand. Victoria still presents a rich heritage of similar monuments which could easily support this kind of treatment.

*

Martin Segger is an architectural historian, writer, and urban critic. He has written extensively on Victoria’s built environment. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of BC, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on BC historic and decorative arts. He is group-coordinator of the UNESCO Victoria World Heritage Project. [Editor’s note: Martin Segger has recently reviewed books by Michael Prokopow, Raymond Biesinger & Alex Bozikovic, Allen Specht, Liz Bryan, Michael Kluckner, and Marc Treib. He reviewed two previous exhibitions at the Wentworth Villa Architectural Heritage Museum: From the Ground, into the Light: Organic Architecture of the Islands, 1950-2000 and John Di Castri, Architect, A Retrospective (1924-2005) for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Empire’s remote rural estate outpost”

Thank you! Most interesting!

You’re welcome, Graham. Many gems of historical architecture were, and still are, to be found in and around Victoria.