Revisiting psychogeography

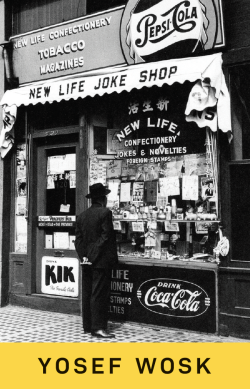

New Life Joke Shop: Travels and Observations

by Yosef Wosk

Victoria, Ekstasis Editions, 2025

$26.95 / 9781771715805

Reviewed by Trevor Carolan

*

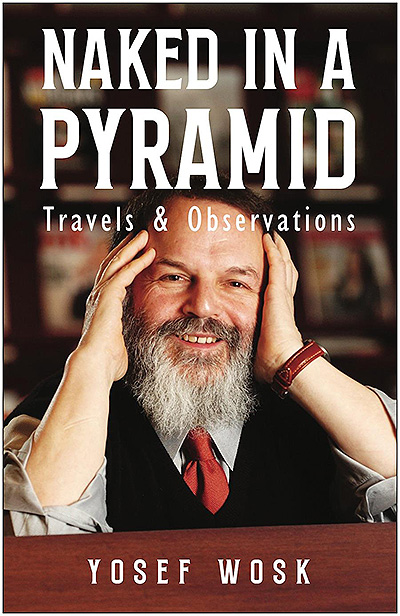

With its title derived from a 1957 black & white photograph, by Fred Herzog, Yosef Wosk’s new collection extends the existential terrain he explored in his last book, Naked In A Pyramid. Both feature the same fitting subtitle, Travels and Observations. However, if the Pyramid tales were heavy on the author’s far-flung travels, these new accounts, plumb interior realms in addressing what Wosk calls, “a confectionary, a philosophical variety store, a word emporium of observations on Ageing, Arts, Books, Charity, etc.”

Included are meditations on collecting, criticism, death, holocaust, imperfection, quest, technology, and on what last time he called Psychogeography.

Back in the day, Smoke and Joke Shops sold tobacco, sodas and sweets, newspapers, comics. You might find stamps and coins, or packs of sports cards. There’d be souvenirs for stray travellers, then the silly stuff—whoopee cushions, itching powder, novelty hats—and for more worldly purchasers, plastic-wrapped “hygiene” and “men’s” magazines that ended up in the barber shop. Somehow, joke shops faded away ahead of video stores, when lottery and phone-card outlets sprang up instead. Nostalgia is no match for limitless texting and instant millionaires.

Wosk doesn’t sentimentalize, and his didactic narrative style still leaves room for steady orders of Borscht Belt comedy. In his opening account of a visit to the former Soviet Union, a terminally Bleak House destination, he recalls a typical Russian story involving the secret police:

A Visit from the KGB

Back in the darkest days of the Soviet Union, a KGB agent goes into a ratty old building. He walks up several flights of stairs and knocks on the door of a dingy apartment with a name plate that says DAVIDOVICH.

No one answers so the agent pounds on the door again until finally an old man in a shabby coat appears.

“Does the tailor Davodovich live here?”

“No.”

“Who are you?”

“Davidovich.”

“So why did you say Davidovich doesn’t live here?”

“You call this living?”

This comes in “My Life As a Spy”, the book’s main travel story. A youngish Wosk volunteers with a friend to go behind the Iron Curtain and contact refuseniks—Jews stuck inside the state who were “refused permission to emigrate, either to Israel or another free country.” An opaque organization handled the arrangements. His task, the author says, was not to liberate these oppressed Jews, “but to bring them news from the outside world and to reassure them that they had not been forgotten.”

From my own experience travelling there in the early Seventies, Wosk’s account of knocking about that grim land in those times is entirely believable. In his reports of paranoiac hotel stays, on the cloying presence of Intourist guides and trying to give them the slip, and being approached by young citizens yearning contact with the outside world, every line he shares is deeply familiar. Never mind James Bond, simply being there was a cloak-and-dagger experience. Bugged rooms, the dearth of everyday menial comforts, the furtive approaches made to trade virtually anything from the rags off your back to ball-point pens: you were watched. If you were young, you’d be harangued. The Party didn’t blink showing you who was boss. Still, people laughed in private.

“See that building?” his guide in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, asks during another visit. “It’s the tallest in Russia.”

It was only five storeys. She let us wait.

“It’s the former headquarters of the KGB,” she continued. “Even from its basement you could see Siberia!”

Travelling the southern Islamic “Republics,” surreptitiously meeting persecuted families and individuals in towns along the ancient Silk Road—Samarkand, Tashkent, Bukhara—the pair encounter living examples of the absurdist situations that made books by Kundera, Solzenhitsyn, and others catnip reading for us in the West. As spies, Wosk reports they were, at best, well-meaning bumblers; but they had the nerve and naiveté to give it a shot, at genuine risk to themselves. That counted back when, “It felt as if everyone was guilty of something even if they didn’t quite know what it was.” That’s precisely what it was like. Timely? Alas, it’s probably what some are angling for south of the border nowadays. Not to worry: as Stalin liked to reassure, “Good citizens need not fear!” Meantime, Wosk continues searching “for peace and freedom in what used to be such a promising new world.”

Much that follows consists of addresses or talks that Wosk has presented at awards or philanthropic arts and cultural occasions. His civic-minded family has been notable for its generosity. If you’ve heard him speak publicly, he’s effective; and if you’ve heard him wail his nigun, a wordless, soulful keening direct from this dusty world to the Senior Management upstairs, then you’ll understand what Soul Brother James Brown was singing about on his knees.

A series of pensées or epistles allows Wosk to expound on his understanding of the subjects mentioned earlier. On books, of which he is an aficionado, he articulates his views on design, binding, quality of ink, mill of the paper—how to appreciate a fine volume like a precious wine, its fragrance, weightiness, visual appeal. Seldom averse to sharing a good sidebar tale, he also shares the story of Zen Master Tetsugen, borrowed from Paul Reps’ and Nyogen Senzaki’s peerless Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. Books are involved, of course; but there’s a lot about compassion, charity, about how one becomes beloved. Wosk is an ordained rabbi: you don’t share these stories without knowing how they are practiced.

In a conflicted city like present-day Vancouver, genuinely virtuous civic gestures matter. In an address on being presented with Vancouver’s Freedom of the City Award in 2022, he reprises Freud’s argument in Civilization and Its Discontents, that in agreeing to, “live relatively close to one another, [t]he price we pay is giving up some of our freedoms in exchange for other benefits such as culture, law enforcement, infrastructure, education, health, and social services.” Then he turns poet, asserting “Remember the moss and the mushroom thriving in lavish rainforest where each drop is a diamond and morning-dew a jewel of the resurrected dawn. Ours is a Garden City—every garden has its rose, each rose its thorn…” Touché.

Conflict prompts his thought, “Except for the transcendent Principle of Unity—the singular, undifferentiated Essence from which everything emanates, all that exists, with few exceptions, seems to partake of a series of dualities.” In Chinatown that’s called Yin/Yang. Accordingly, the ideas of God, a Unified Field Theory, Reality itself—all come under discussion, with a little room as well for consideration of Sport, of competition as surrogate subset of conflict.

His sparkling reflection on Criticism—compulsory reading, I’d advocate, for wannabee reviewers— explains that, “Creative criticism is humble, not arrogant…The critic must have the courage to see what exists and speak its name but should not seek to humiliate the one being critiqued.” It’s a matter of regard for, “both the artist’s struggles and achievements.” Not to do, “we tend to become apologists for mediocrity.” Could the ethical perspectives of the still-lamented Canadian arts critic, Robert Fulford, be synthesized any better?

The yearning for a sense of greater justice percolates throughout this collection. In “On Nazis,” Wosk considers that, “the Nazis didn’t just kill people, they murdered love, hope and the last vestiges of decency. They perfected murder; shamed humanity. That, after all the commentary, is their only legacy.” He adds further, “Our challenge is to be as active in pursuing peace as we are in waging war…fierce yet peaceful warriors.” While it’s off topic, but with so many needing insight right now, am I alone in saying I’d appreciate hearing from someone as wise as this man on the horror-inquisitions of our present generation’s nightmares in the Ukraine and Gaza?

Regarding psychogeography, that fascinating term he presented in his Pyramids text, Wosk is surprisingly brief. “It is the cosmos becoming conscious of itself through the agency of human awareness,” he asserts in an Alan Watts-like moment. Here, perhaps the principle of interconnectedness— what Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh termed interbeing—is implicit. In a longer, searching essay, “The Future of Knowledge: Contemplating Museums,” he appraises Marshall McLuhan and Lewis Mumford: “If technology is the thing, innovation is the fuel,” he writes. Then, moving on, he notes how many institutions “are underwhelming in their presentations and stifling in their bureaucratic attitudes,” adding an unsourced but germane critique that, “Universities are trying to meet 21st century problems with 16th century philosophy, and working in an 19th century organization.” No argument there. However, it quickly grows complex, with Wosk proposing that, “in the not-not-too-distant-future innovative technologies will be surgically implanted within us. Virtual Reality and Artificial Intelligence will be complemented by Brain-Technology Interfaces…” This agent is not qualified to assess those techno-developments. What I can appreciate is his view that, paraphrasing his luminous PhD mentor Thomas Berry, “We are in the midst of [civilization’s] next Great Conversation.”

The late-Tom Robbins said he reckoned that the first human words uttered were probably, “Tell me a story.” Similarly, Wosk suggests the universe begins with story and will end with one. He has previously declared himself “an imperfect messenger,” so his homilies are apt to wander into the realms of the sacred, but that’s the deal. Borrowing from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, a work he is unusually drawn toward, Wosk maintains, “Old Men ought to be explorers.” Yet for all his peregrinations, in “Reflections Upon Turning Seventy,” he confronts the fact that after a lifetime of searching for answers, for the greater truth, he still doesn’t know.

In the Smoke’N Joke shops you might never really find what you were looking for. Conversely, as Bob Dylan writes, how long can you search for what is not lost? That’s the thing about eternal verities, one of Wosk’s go-to mojos. Like aspirins, we stick with them because they work, especially on headaches in times like the here and now. He concedes that he has learned to choose his battles and abandoned most wars. Archetypally, acquiring wisdom obliges that we share it with others—a giving, he intimates, that also involves reciprocity; in moving us toward, he proposes, an “emerging economy of presence.”

*

Trevor Carolan writes from North Vancouver. His work appears internationally. He teaches Environmental Studies at UFV. His Road Trips: Journeys in the Unspoiled World is published by Mother Tongue. [Editor’s Note: Trevor Carolan has reviewed books by Yosef Wosk, Richard Cannings, Tom Aversa, and Hal Opperman, Jonathan Manthorpe, Michael Schauch, and John Lent for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster