Recognition and epiphany

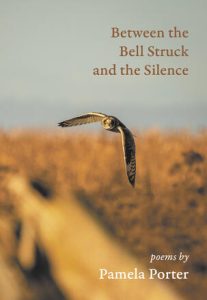

Between the Bell Struck and the Silence

by Pamela Porter

Qualicum Beach: Caitlin Press, 2024

$20.00 /9781773861418

Reviewed by gillian harding-russell

*

Elegiac and redemptive, Pamela Porter’s Between the Bell Struck and the Silence brings brief moments of recognition as those symbolized by the image “between the bell struck” and “the silence” of epiphany that follows. Echoing John Donne’s bell image in Meditation XVII of Devotions on Emergent Occasions as a reminder of our mortality and need for conscience, Porter lends resonance to her soul’s search while immersing herself in nature and struggling to come to terms with her past.

Intricate and integrated, the poetry collection features an owl motif that flits through her poems to angle down and look the speaker in the eye, as does the wolf in a landmark poem where the poet comes face to face with her problematic but loved father. Poetry is a genre that focuses on images and the minute as microcosm for larger human concerns, and Porter manages a wrenching of the soul through select detail and an imagery that draws on nature and the human.

In the opening poem “Dust to dust,” Sidney resident Porter (Likely Stories) weaves elegant stanzas of alternating one, two, or three lines to introduce a “a forest of towering firs” where owls live and provide the life and soul of the landscape. While “a gust of wind/could take the house,” and nature is seen as a danger to humans at the beginning of the poem, the “buzz and crack, as firs felled one by one” marks an ambiguous turning point where humans have gained a dangerous upper hand in the order of nature. The speaker notes the “quake” as the “great firs” “crashed” to the ground and how “the owls rose and flew”:

I’d never spotted the nests, so high in the thick of the forest.

And no official sent to look.

Five, six, seven fled as one, resembling the souls of those

just now leaving the earth.

In dovetailing reversed lines, the closing verses repeat the opening lines with an expression of subdued shock and misgiving at the sacrilege: “Write it in your holy book. Open your hands over all you once knew.” Just as the owls open their wings to escape, so the speaker opens her hands in tacit outrage and hurt.

Conscience and a sadness of trauma likewise enter the home rather than nature in the beautifully woven verses in “Call me by my name,” where “something forbids me to speak” and the “language of this house/is silence”—so that what is known is repressed and unspoken. Again, the image of the bell struck enters this poem that speaks obliquely in a manner that would please Emily Dickinson with her artistic dictum, “tell it slant.”

And the shadows grow large across the yard,

but hold no language, as the tongue

that never collides with the bell, never

measures the bell struck and the silence.

Only in part 6 and the final lines of the poem does the psychological injury to the speaker become known. “There are no bones inside the heart./How then does it break,” she tacitly implores herself and the listening reader.

Glimpses and tableaux within poems set scenes, and some of the more narrative poems, such as “The Lieutenant” and “The Unadorned” provide an elliptical background and suggest the context for the speaker’s suffering. In the first, with the speaker we suffer “the war in the house” between the Lieutenant and his wife, and from blaming the bad-tempered husband the reader shifts loyalties to consider the wife’s atrocities in “The Unadorned.” Here the “girl” is seen to have “climbed high enough/into the branches of the sycamore” to see clearly into her mother’s bedroom where she witnesses her mother’s infidelities.

One of the most poignant poems is “‘The silence of the dead is all we own’”—the title borrowed from Patrick Lane’s “Small Elegy for New York.” In this lovely poem, during which the speaker goes about her daily chores of feeding the horses in a rural setting, she becomes aware of a “presence,” and looks up to see a wolf, “dark faced with grey at the tips of its ears” by a “nurse log crumbling through time/and weather”—”…so I stood/eye to eye with the wolf, how the yellows of its eyes/pierced mine….”

As the speaker considers that the wolf must have “swum the strait under moonlight” to arrive where he has on the island with her, “something/inside me knew: he had come in a form in which I/could see him—my father, come back as a wolf.”

By turns, we become familiar with the speaker’s personality and her introversion, and in no other poem is this need for meditative seclusion inside nature so clear as in “Personal distance.” Here the poet admits that she likes to venture out in the morning before anyone else, and treasures her solitude with the peace and creativity it allows her.

So not to startle the new buds,

I whisper to them that I too am shy;

how hard it is, what effort to form the words

when someone happens along the trail to talk,

Before this interruption to her thoughts, her “ear” was “listening for news the ferns have to tell,/and the mosses who cover the nurse log” with “the everlasting silence of the soul.” Again the “nurse log” comes up that will return in the poem “‘The Silence of the dead is all we own,’” where the wolf of her father turns up to greet her soul with a kind of harsh understanding that is not unmixed with love.

Between the Bell Struck and the Silence contains poems of immense beauty while the speaker seeks redemption for psychological injuries of the past and finds it in nature. Porter’s deft handling of “a music of imagery” (to borrow T.S. Eliot’s term), and her pitch-perfect tone makes this collection a poignant and rewarding read. Here is a poet at the height of her talents who has published yet another memorable collection.

*

A poet, editor, and reviewer, gillian harding-russell has published five poetry collections, most recently In Another Air (Radiant Press, 2018) and Uninterrupted (Ekstasis Editions, 2020), both nominated for Saskatchewan Book Awards. Also, The Alfred Gustav Press released a chapbook Megrim (2021). Her work has been published widely in literary journals across Canada, including most recently poems in The Queen’s Quarterly and reviews in The Fiddlehead. She lives on Treaty 4 territory. [Editor’s note: gillian harding-russell has written about collections by Svetlana Ischenko, Donna Kane, Diana Hayes, Susan McCaslin, Marlene Grand Maître, and Ian Thomas in BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster