Do we know the man?

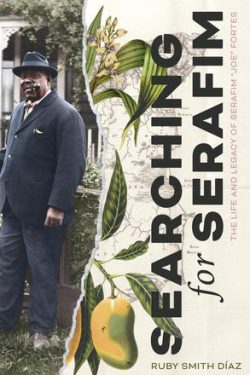

Searching for Serafim: The Life and Legacy of Serafim “Joe” Fortes

by Ruby Smith Díaz

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2025

$21.95 / 9781551529752

Reviewed by Wendy Burton

*

Searching for Serafim is described as an in-depth revelatory biography of a well-known early Vancouver personality: “Joe” Fortes, lifeguard and swim instructor in the early 1900s in Vancouver. Fortes is a legendary figure from the early days of Vancouver, guarding what is now English Bay and its swimmers. In the days when the beach was divided into male and female sections, enforced by Fortes, the recipients of his watchfulness mainly children.

Fortes is honoured in plaques, a fountain with the inscription Little Children Loved Him, a library and restaurant with his name, and the Vancouver Historical Society named him Vancouver Citizen of the Century. He is also remembered by those of us of a certain age.

But is he known?

Learning to swim at the saltwater pool at Second Beach in the 1950s, I heard his name, the mythical rescuer of many, and was told he taught my father (born 1924) and his brother (born 1920) and sister (born 1922) during the days they would go unescorted to English Bay and return at dusk, sunburned and full of tales of their swimming lessons. Imagine my surprise, and the chagrin of my family, when I discovered, and announced at the family dinner table when I was an annoying teenager, that “Joe” Fortes died in 1922.

Ten thousand people lined the streets around the centre of Vancouver, many crowding into Holy Rosary Cathedral for his funeral, according to local lore and repetition of the few facts known about Fortes. That so many people mourned his death is seen as a tribute to the man and his acceptance into the Vancouver settler community.

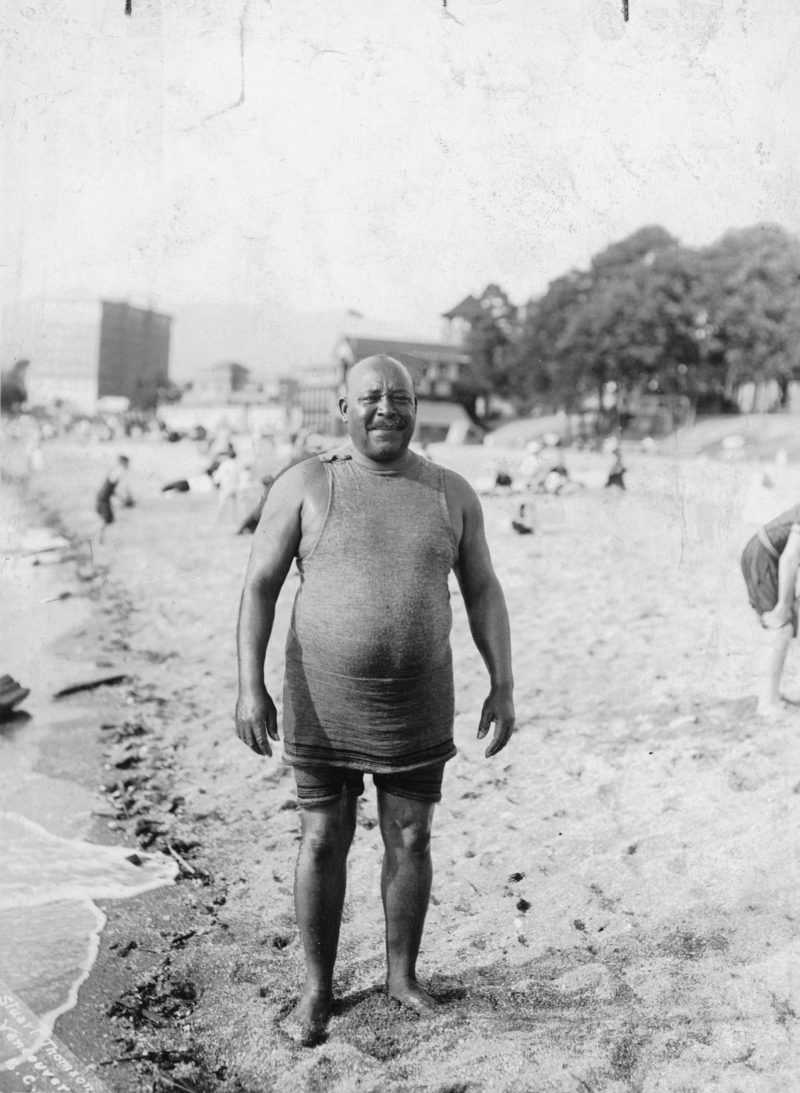

Ruby Smith Díaz sets out to find out more about this man and situate him – alongside herself – in late 1800s-early 1900s Vancouver. She begins by resurrecting his first name: Serafim. What little known of this man is woven into the fabric of early settler Vancouver. What I, as well as many perhaps, did not know until I saw a clear photograph of Fortes, was he was a Black man whose colour was literally erased in most contemporary accounts of his feats or, worse, excused with the demonizing “but.”

Much has been written about what little we know of the man Serafim Joseph Fortes. The same skimpy and well-loved stories of this mythical man who kept the beach of what is now called English Bay safe and taught a generation to swim are repeated unexamined.

Endearing stories. Comforting stories of kinder times, when ‘we’ lived, thrived, and survived, as a community. His stories of inclusion are often set against the anti-Asian riots, the Komagata Maru Incident, and – the ongoing dislocation of Indigenous peoples and their communities, including the one easily seen by Fortes directly across the inlet from “English Bay.”

Díaz seeks who Serafim was, starting with resurrecting his name and piecing together what few facts exist about him. When she encounters a blank – a gap – she colours the portrait with her own life experiences as a minority in the dominant white Anglo-European culture of 21st Century Vancouver. Reading between the lines of what is often repeated and reading against the grain, Díaz assumes she and Fortes share a culture, including what Fortes would miss, claiming scents, food, sun, warmth, and the company of others from the Caribbean.

The photograph presented early in signals Díaz’s intention. She has taken a well-known photograph of Fortes:

…and photo-shopped herself into it, so she is standing beside him:

Ruby Smith Díaz using image of the author by Keith William Miller, as well as a photo of

Serafim Fortes from the City of Vancouver Archives [AM336-S3-2-: CVA 677-440]

Díaz literally projects herself into the biography, frequently adding her own experiences to information about Fortes she presents. If the reader is aware of the facts known about Fortes, they do not come to know him any better or more than before she produced this biography. It is a memoir of her search, her overlay of her daily lived experiences onto the life of a man dead now more than one hundred years. As a memoir of research and discovery, this book is a good read. The search of the title leaves us with more questions than answers and brings Serafim Joseph Fortes into the present in a larger, fuller context. We learn more about Díaz than we learn about Serafim Fortes. Who he was remains to be discovered, guided perhaps by the unanswered questions Díaz leaves us with.

Using speculative archiving, Díaz often uses qualifiers such as “maybe,” “could have been,” “might,” “in one of my imaginings” to remind us she is building a fuller picture of Fortes from very few facts.

Her dissection of what she identifies as targeted racial violence aboard the Robert Kerr, the vessel he worked on, could as easily be interpreted as violence done not only to Fortes but to many others on board the ship, according to the First Mate’s log. What is evident is Fortes, along with others working on the ship, was the victim of a violent man the officers and captain could not control. One does not know how Fortes himself interpreted the actions of Able Body Seaman Anderson.

To accept the conclusions Díaz presents, I ask for more explanation to support her claims. What, for example, can be made of the record of Fortes’s harassment of members of the Chinese community? Díaz documents the newspaper reports, but does not explore the juxtaposition of a racialized man living in a white supremacist society – she writes eloquently of what Fortes must have made of the decision of the Vancouver theatre community to host The Clansman, a play about – yes – the KKK – with his documented antipathy toward Chinese inhabitants of Vancouver. Díaz provides an overview of the theft of Indigenous lands that made settling Vancouver possible, but does not explain Fortes’s apparent indifference to the dislocation of Indigenous communities living in what is now Vancouver.

Díaz declares she re-imagines him as an uncle she never knew. Doing so, she frequently does a summary-like explanation of topics such as the history from 1834 abolition of slavery to 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and, presumably, Black refugees coming from the US after the civil war. (Fortes arrives in Vancouver in 1885 from England, as a result of the ship he was working on breaking down so completely he was effectively stranded in Vancouver.) Was Fortes a refugee affected by the Fugitive Slave Act? Nothing in his history of working the ships from what is now Trinidad to Bristol and on to Vancouver tells us he was being pursued. Yet Diaz concludes “It was within this context of hyper surveillance that Serafim arrived in Canada, from one British colony – emancipated but not free.” Fortes arrives in Vancouver in 1885, after Confederation, decades after the events in the summary. Diaz makes a side reference to West Indian Domestic Scheme – which happened 20 years after Fortes died.

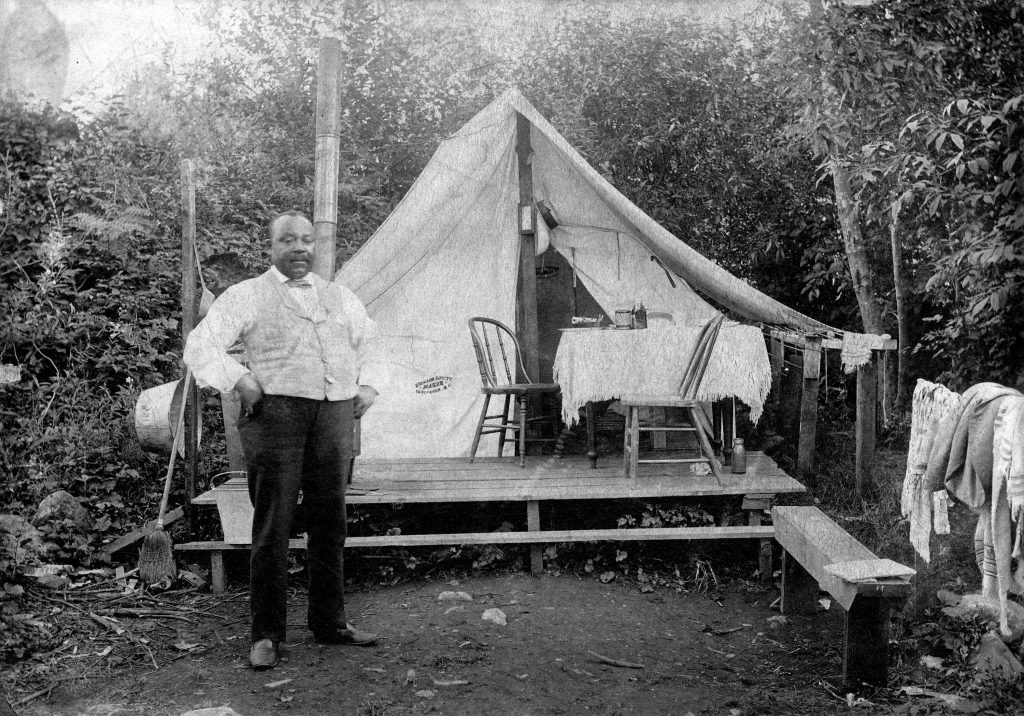

It is the conflation of historic facts with details of his life that obscure the effort to tell the reader more about Fortes. What was his experience as the “the only person of Caribbean descent living in Vancouver” according to Díaz. This question is answered with allusions: he was living on the beach in a tent until he was officially hired as a lifeguard and was paid, he was a special constable whose beat was the beach and some notorious bars, and he seemed to have special duties with regard to Chinese men on the beach and in the streets. People came calling, and he hushed his guests, women from the household of one of the two Black families living in Vancouver. Díaz believed this family may have been his only close friends.

“I imagine Serafim’s experiences through my own stories.” This is where it gets interesting. Was her starting research question how much her experience mirrored his? Was she looking for herself in his biography? How did she decide her experiences are his? In her re-telling, Serafim’s life is “shaped by the thoughts, observations and opinions of the [person] who [has] the power to hold pen and publish.” Díaz projects so much of her life onto her search for Serafim he is lost in the process.

Serafim’s story remains lost, I fear. What remains is stories told by white settlers, newspaper accounts, and biographical sketches that repeat what is known. Díaz concludes Serafim Fortes was “a poor man of African and Spanish descent who managed to gain the respect and trust of white people in a time when whites actively set laws and policies to exclude non-whites from Vancouver society … He became a hero to whites because he survived the barriers that they themselves placed against people like him.”

Who did he love? What did he think about, sitting in his tent in the dark, looking across the inlet to the Indigenous village that was shortly to be destroyed? Did he know himself implicated in the theft of Indigenous land, including the land his canvas tent occupied for many years? What stories would Serafim want us to know?

He was a devout Christian, about which Díaz says very little. His weathered Bible, his attendance at Mass, and his demonstrated piety are signs of a man for whom his faith was important. Díaz ponders the absence of Black women (or men) who could have been possible romantic interest. We knew little. We know less now, as what is known is obscured by her – she crowds him out of one of only a few photographs of this man.

The absence of his story in his own words is permanent. Díaz is “telling my life in my own words,” and for that alone this book is worth reading. She interweaves the chronology of research with poetry. She provides citations worthy of an undergraduate essay. She provides an index.

Searching for Serafim concludes with a poem, ‘Soliloquy for Serafim,’ where she weaves the fragments of his story into a compelling whole.

Serafim Joseph Fortes died as a result of a winter rescue, going into the frigid water of the inlet to save two white men. By then he would know what exposure to cold water would do to him, but he went in anyway. He was 57. That decision, that heroism, is worth remembering.

*

Wendy Burton is Professor Emerita at University of the Fraser Valley, where she taught academic and work place writing, story-telling, diversity education, and Indigenous Adult Education. In 1997, she earned a doctorate for her feminist analysis of story-telling as knowledge claims. Throughout her work life, she wrote creative non-fiction, long and short form fiction, and poetry. Her debut novel Ivy’s Tree (Thistledown) was published in 2020. She writes fiction and creative non-fiction. Her most recent essay is “Meditations on the Headstand,” Folklife, Winter 2023. [Editor’s note: Wendy Burton recently reviewed books by Gina Starblanket (ed.), Danny Ramadan, Jo-Ann Wallace, Chris Arnett, Susan Blacklin, and Tara Teng for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster