Here With Us In This Home

by Deborah Vieyra

Just Another Day in Paradise

Her first TIA happens at a seaside resort. She comes to me, her language elsewhere, grasping only to the phrase “my heart feels empty.” The phrase dawdles from her mouth on repeat, the same intonation in every iteration, the same surrender in every execution.

My heart feels empty, my heart feels empty, my heart feels empty.

Her face sags and that stupid ad with the stupid voiceover rides in like a night in crackling static to save me from my helplessness. The stupid signs. From the stupid ad. Drooping face. Slurred speech. Extreme confusion. She is having a stupid stroke. My dad is watching some stupid television show, maybe sports, maybe some other stupid thing. My mom comes to me on that stupid couch. My mom, she comes to me while I am there half napping on some stupid seaside timeshare resort couch and I become my mom’s mom.

I remember a man calling to me on the beach. I was a young child and the Whites Only / Slegs Blanke signs had just recently been torn down. (Honestly, I don’t remember the part about the signage because maybe it wasn’t the sort of thing you talk about with a small child. I learned about them in a school textbook a few years later when we had to digest a history still too hot to eat). Still, I only recall white people on this beach: dunked by violent waves, white-washed in the sea, buried (whole-bodied) in the sand with only the burnt pink heads sticking out. I remember a man calling towards me with his big bony finger like the beginning of a fable that has lost its moral. I was so small and I clung to my mom and I would not go with him because my mom was safe and he was scary. I remember we spoke, my mom and I, about this incident—after—and this is when she taught me the word beckon. (This is how little girls everywhere learn words—from incidents.)

Now, she, my mom, is coming to me, her daughter, at a seaside resort, for this: to hang on to me while something, someone beckons her to a dangerous place. But my arm has grown long like an adult arm and hers is now only that of a small child and something is beckoning her and I have to remind her what the word means—beckon—and why she mustn’t go with him. My heart feels empty.

“Dad!”

“Dad!”

and

“Dad!” again.

That’s my word now, in the key of hysteria—always in a key of hysteria, it feels.

My mom speaks in Afrikaans, then English, then both. She wants to go pee, her pants are falling down, we need to get her to Emergency, her underwear is falling about her knees and we have to get her pants up and where are the car keys even. My dad stage whispers, “I think she’s having a stroke. I think she’s having a stroke.” The moment is all comma splice, no punctuation strong enough to separate the independent clauses. Here on holiday in a timeshare, it’s been planned for months, what a great deal it is, an extra night’s been thrown in, we’re at the seaside, we’re right on the water’s edge, waves are crashing mercilessly on the shore, there’s an informal settlement just outside that six separate holidaymakers have now complained about, the management doesn’t know what to tell them, the road to the resort complex has poverty on both of its sides, like a blurted out secret that has failed to keep itself.

My mom’s having a stroke and we’re not even sure where the closest hospital is. We, my father and I, we stumble her to the car and somehow get her to the somewhere hospital that we somehow find and who knows if she’s dying or having an existential crisis or what the difference even is.

She stays in the hospital for days, forgetting and forgetting. By the time the next hospital visit comes a few weeks later, she’s forgotten the first.

Your Ticket to Paradise

Dementia derives from the Latin root demens: “being out of one’s mind.”I keep wondering if my mom is out of her mind, where is she then, and has anyone taken her spot inside?

I hear dementia is related to oestrogen production, to deafness, to depression, to tinnitus, to genetics, to alcohol use and misuse, to smoking, to obesity, to being old, to doing too little, to getting too stressed, to ageing—definitely that—mostly to ageing, to getting old, to not wearing a helmet when you go skiing, to cell phones—dubbed Digital Dementia—to poor fucking luck. Depression, depression, depression. Social isolation, that’s a big one, yes, especially after the pandemic. Did she even leave the house? Obesity. Air pollution. Not getting good quality sleep. Being isolated. Depression. Depression. Depression.

My mom’s long forgotten that my ex-husband exists but still hangs on to the names of the local birds (fork-tailed drongo, oystercatcher, plover, hadeda—ibis, the hadeda ibis, her favourite sound, no, second, to the dishwasher?) She’s forgotten about the chicken sosaties we’ve just decided to have for dinner but not the opening of The Rubaiyat of Omar Kayyam.

Awake! for Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight:

Yes, Mama. Carpe Diem, Mama.

We, my dad and I, we sit at the dinner table: potatoes, our chicken sosaties too—what did we do before the air fryer?—and the salad, with those strawberries, three punnets for ZAR50.

My mom sits on the loo, forgetting why she’s there. If it’s like yesterday, she’s rolling up toilet paper in her hand to get ready for the main event and then rolling more and more until the whole roll is almost off its roll like a show where the opening act goes on forever as the headliner’s gone AWOL.

My dad calls to her, “Are you coming to join us?”

“Why?” she asks, “Have you fallen apart?”

We wait for her—we won’t say grace until she arrives. I take a nibble of a strawberry from the salad, my dad a bit of potato. We don’t tell on each other. We’re complicit, the two of us, my dad and I, sharing sanity, not yet officially exiled from our minds—if we don’t think too hard about it, we’re having fun. I love the nudge-nudge-wink love that has become a part of my story with my dad.

Paradise on Earth

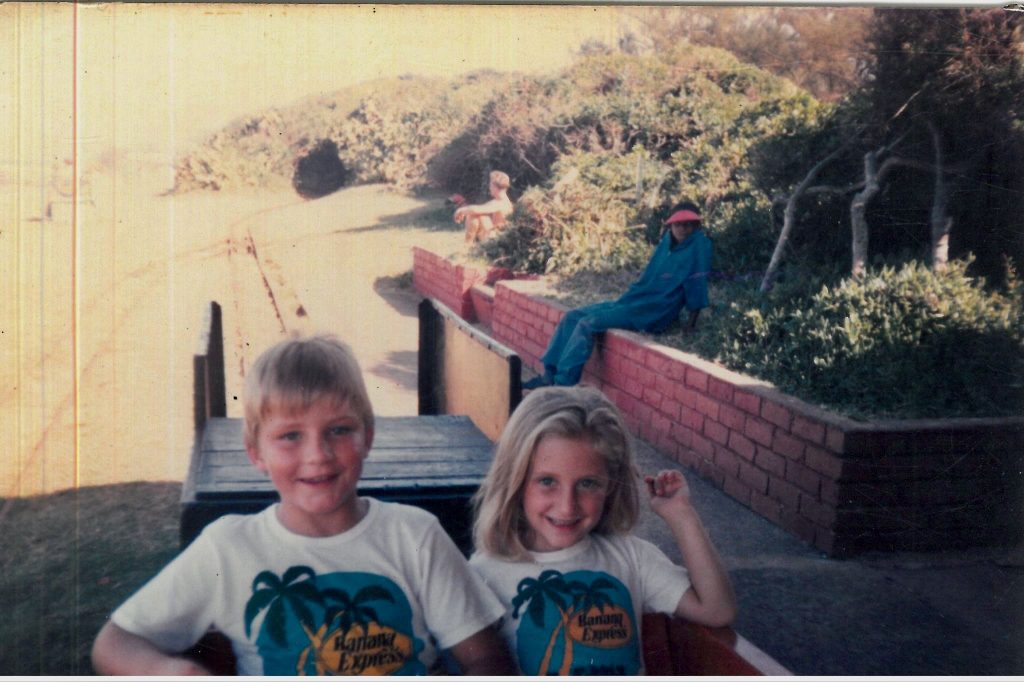

The Banana Express was a little tourist train that ran along the Kwazulu Natal South Coast, just near Happy Wanderers where we used to spend our holidays.

You can see the Banana Express in this photograph:

That’s me and my big brother in matching Banana Express t-shirts, about to go for a ride along the little track. It’s cute, the palm trees; tropical, the area. I remember avocados the size of a human head, and not my human head but my dad’s human head: that big. I’m thinking it’s still Apartheid in this picture of the Banana Express because democracy only came in 1994 when I was ten and, in this picture, I think, I look younger than that.

Look back at the picture. See the man in the background sitting on the brick wall? See him? I don’t remember him nor believe I ever knew him, but he is in this family picture. He was a worker there, at Happy Wanderers or the Banana Express. I think. I think that from his blue overalls. Those are workers’ overalls.

Now, in 2025, a political party exists in South Africa that has performatively conjured the Black South African worker from invisibility: they have actively remembered him. The EFF (Economic Freedom Fighters) come to parliament dressed in the overalls and hardhats of labourers, or the fem pinafore and head doek of the domestic worker. The EFF has been around for over a decade. They’re black nationalist and communist—and they’re in parliament: the Apartheid government’s nightmare made real. After all, the powers-that-were built their propaganda machine on the threat of the Swart Gevaar (Black Danger) and the Rooi Gevaar (Red Danger)—and very often got the two colours confused.

There is much to be said about the Economic Freedom Fighters of today, like that white people are terrified that they’re going to take the land back by force and then “we’ll turn into another Zimbabwe.” But that’s not the whole story. Dramatic in-fighting and abdications of leadership within the EFF have taken up some real estate in the nation’s headlines and there are various corruption charges stacked against the EFF leader, Julius Malema—so about that fighting for economic freedom for all, who knows?

I don’t want to talk about Julius Malema, really, or the EFF. I just think it was pretty clever what the party did with their parliamentary attire, you know, artistically, theatrically, aesthetically, to make manifest in the public consciousness the invisible people that built and sustain and dig and sweat and die and die for this place.

Regardless, my family photos need to be cropped to look cute; parts of our memories need to be edited out to have them happily.

Maybe I’m also out of my mind, a node in a collective brain that is demented.

Historian David Andress’ uses the term cultural dementia to talk about the senile brain state of the West and its relationship to a savage colonial past—forgetting is one way to create at least a performance of absolution from your own brutality. Andress is talking about the U.S., the U.K., France, and the demented brain of Empire. Think MAGA, think Brexit, think Le Pen. Think countries that matter—not some embarrassing cousin of white supremacy at the bottom tip of Africa.

Regardless, when I hear Andress say cultural dementia, I hear him gossiping about us down here.

Dreaming of Paradise

In my dream, I grow an old man beard and my mom gets lost inside it. I’m clumsily braiding my beard, clearing the way so that she can find a path out, when a gentle don’t-wake-the-baby Dad voice floats in from the adjacent room and into my consciousness:

“Do you want me to call Deb?”

I am called regardless and appear in their room where my smallest mom lies on the vastest floor. This vertical life had gotten too much, and she seems to have flipped her orientation. I think of the vertigo of being human, of being on these two legs, us, upright, heads in the clouds and further; sometimes all we need to do is come back to earth.

We fall—in love, from grace, to the ground.

Paradise Lost

TIAs are transient ischemic attacks. I didn’t always know this—nor do I want to know this now—yet I toss the acronym around with ease as if I belong to a club. “Ischemic” has to do with blood flow to a body part. Ischemic. The consonants get stuck in my throat: a clot unto themselves. They think TIAs are what my mom’s been having, but tbh it’s hard for even the doctors to be sure. Either way, whatever she’s been having, she’s having the same thing now.

My mom vomits into my hand, speaks in the dialect of the Surreal, conks out and back. I’m driving the little car she used to drive—it’s small and dubbed Half Loaf because that’s what it looks like and that’s how she thinks. I can’t find the ER because I have a terrible sense of direction, even in a crisis, and I always turn left when I’m supposed to turn right (I got that from her, my mom, she’s the same) and now it really matters this perpetual disorientation because she—is she dying now?

South Africa has a two-tier healthcare system: public and private. According to our constitution, everyone has the right to access healthcare. The public has the right to public healthcare. The trouble is that nobody really wants to be in the public. It would appear that healthcare is a topic best tackled in private. So: there’s free healthcare for all except those who don’t want to use it, which is everyone who can afford not to do so.

When in 2023, the government passed the National Health Insurance Act to “achieve universal access to quality health care services in the Republic in accordance with section 27 of the Constitution,” opposition went viral. Fair enough. The public utility Eskom has had a hard time keeping the country’s lights on—so how could we (whomever we mean by that “we”) trust them (whomever we mean by “them”) with our very lives?

Add to this that Apartheid, “the state of being apart,” divided up the land and its services along racial lines. The coordination of services to areas that were outside of white centres was, it may come as no surprise, severely lacking. One might say that 30 years after the end of Apartheid, the ghost of the body of Apartheid remains—except that when it comes to the country’s cartography, He never really became a ghost at all.

I once visited my uncle in Baragwanath, an infamous public hospital in Johannesburg. Most people I have told think this fact is weird because my uncle was white. The story went that my uncle drank himself from riches to rags and then straight into becoming a cautionary tale. There he was, doing MENSA puzzles, leg freshly amputated, on a stretcher in a hallway of Baragwanath. Was that blood or fecal matter on the walls? Was that the sound of a gunshot or machinery collapsing?

I’ve heard the public hospital in my parents’ small white-ish town is better than Baragwanath. But we’re not taking the chance. When it comes down to it, nobody even mentions the chance as an option.

All I can think about is my mom as I struggle to find the Emergency entrance to this private hospital. I will empty out every measly bank account I have to get her care. Where are my socialist ideals now?

This time in hospital, she hallucinates a man called Mike whom she sees standing behind me. She is upset when he leaves. Did we offend him?

She tells one batch of visitors that she’s landed up in hospital because she fell off a horse, the next batch that it was a bicycle, the next that she tumbled down a mountain range. It would appear her Hero’s Journey was birthed in a writers’ room where the air was thick with dissension.

A Paradise Manner

My dad takes Half Loaf to the mechanic—the left light is out and the tire dodgy—right next to Fruit and Veg, where you can get three punnets of strawberries for ZAR50. He tells the mechanic, what was his name, Gavin?, that he needs a car that works to drive the 60 kms to George where his wife is in hospital. She has dementia, he tells Gavin—Gary? Gordon? Was it even a G name? That she’s been in and out of hospital, falling about the place, she has Parkinson’s and dementia and cellulitis and edema of the legs and high blood pressure and a great sense of humour and a penchant for adventure and cholesterol issues and diabetes. This makes her a fall risk and not really even that much of a risk anymore because risk implies future action and the action has already happened, and she’s in hospital—in George—and that’s why we need the car to work—it’s about 50 kms, what is it? — 60 kms away and the trucks on that road and the Kaaimans Pass (we should stop there someday, go down to that beach?) can stall you even if you’re making good time because of the road works on the other side and the trucks, even if you think you’re making good time. We’re thinking, we need care for her, and, that we can’t do it alone. A care home maybe, but.

White people are different with their old people, my dad reports that Gary, Gordon, Simon, Mark, says, For us, it’s a responsibility. We take care of our old people. No question. Not the same for white people, he says.

I think of the isiXhosa word umlungu. The word refers to “white people,” “white bosses,” and possibly to the “dirty white foam of sea waves.” It might come from the word ubulungu, which means “deposited out of the sea,” or perhaps more accurately, “sea scum.”

Fool’s Paradise

A post-Apartheid law exists to protect the ageing:

The Older Persons Act 13 of 2006 intends: to deal effectively with the plight of older persons by establishing a framework aimed at the empowerment and protection of older persons and at the promotion and maintenance of their status, rights, well-being, safety and security.

However, according to Human Rights Watch, this act has been far from implemented:

“Despite the act’s stated aim, many older people who were displaced during apartheid still do not enjoy their right to live independently and within the community, with hundreds of thousands of older people unable to access the basic care and support services they are entitled to so they can live with dignity in their own homes and communities.”

The young victims of the Apartheid system are now the elderly victims of the Apartheid legacy.

During one of her hospital stays, my mom starts remembering.

“I remember,” she remembers, “looking out on the frosted veldt. It got cold there in the Free State and we were barefoot a lot of the time. I remember a policeman chasing a black man. I think the man was in trouble because he didn’t have his passbook. Or he did. But he was in a white area at the wrong time. I remember that policeman chasing the man. I was small.”

“Another time,” she recalls, “I remember my mom crying at the window. I don’t think she wanted me to see. We lived in a dusty mining town, and she was a poet. Actually she was an alcoholic. There are some things you don’t want to remember.”

A Little Piece of Paradise

We walk into Paradise Manor, prospective clients window shopping. This one is on a farm, idyllic in comparison to the institutions that file away the elderly in archives of bleached tile, only to be searched for by the odd family visitor, now and then, when the guilt gets too much.

The inside of Paradise Manor smells like food that can be eaten in small chunks. The scent of cleaning products works hard to disguise the traumatic memory of piss. Collages of photographs, bright construction paper, and lumo highlighters advertise the adventures of Granny D., of Bob, of Simon, the South African Airways Pilot who is still flying in his wheelchair in the living room.

I am the white daughter of a white mother making arrangements with the white owner of the care home. Old white people with little conscious memory are served by people of colour who dote on their every need, feed them, listen to their stories about how they might have had a family once, knit with them—look how many rows you’ve done, it’s almost a square—colour in with them, laugh with them, walk with them. Too easy, perhaps, this reality, in a country where remembering can just get too much.

South African care homes: the final scene for a generation that had a 0 marked on their ID documents because white was neutral.

Paradise Regained

My mom keeps asking when she is going home. Sharon, with her yorkie dogs, explains that in her managerial position of this long-term care facility, she hears this a lot, about going home. Yes, it could be home like where they came from, but it could also be home, she says, gesturing like an amateur actor to a fake sky.

I can’t judge. I don’t think I know what I mean when I say I want to go home or feel a desire to go home. Scrambled eggs for brains, I write in my journal. I write the date in my journal too, followed by depends who you ask.

Before I left Canada to come to this crisis, my mom would ask repeatedly if my ex-husband and I had separated. Again and again, I would have to relive the details of my divorce, sucking more air out of the story every time I told it until I eventually had it totally vacuum-sealed: just said, “alcohol: I wanted to stop.” She liked that.

She has now written my ex-husband right out of her script like a day-player she couldn’t develop into a character with legs. Without the story of marriage to hold onto, she wonders now why I went to Canada. I start to wonder too. If she can fall in so many ways, I think, so can I:

I tell her I had frequent flyer points.

I tell her I was a spy, a diplomat, a vegan fur trader.

I tell her I was an arctic explorer who got lost.

Trouble in Paradise

Siena is my mom’s best friend. My mom says that God put her and Siena together, but it was most likely the neighbour who did it when Siena was recommended to my mom as an outstanding domestic worker. Siena is with me when my mom has one of her alleged TIAs. Siena weeps for my mom on multiple occasions, tells me sy’s ‘n ander sort mens—a different kind of a person. I take Siena home, telling her in my white-speak that she’s part of the family, that she means so much to us, god shut up deborah, what are you saying? I take her home to an informal settlement at the end of the same farm road my mom’s care home is on. South Africa has been quite proficient at structuring both its rural and urban areas to keep labourers out of sight and in desperate precarity. Siena knows the care workers from Paradise Manor—my man’s se niggie! Daai vrou—sy’s in my kerk.

An Ethics of Care. What a joke.

I feel demented.

I want to think all these complicated thoughts, look at context, understand it, but I’m grieving and sore and raw and I don’t know anything except that I want my mother back from where this condition has taken her. Her naughty eyes are still there, and her jokes keep going like nobody informed them that the show was closing.

“Did you see the horses today, Mom?”

“Neigh.”

The signature inflections in her voice are there too—“Hello, my darling and beautiful daughter, hello Baby Bear”—and that strange innocence she’s always had.

And so is that impenetrable suffering that allowed nobody far enough in.

“How are you feeling, Mom?”

“Not great.”

“What does not great feel like?”

“I don’t know but I feel it everywhere.”

She always wants to brush her hair and loves a book on etymology and that one about the world’s stupidest signs. I have her here, all of that, she is here with us in this home, here, this care home, this Paradise home, this complicated home, this homemade home of people stuck together with a despite-it-all love. She is here in this home not in that one (points to the sky). But she is sending parts of her to survey new lands.

The parts that are off are the ones that were in charge of our long conversations about the diction and syntax of everything from road signs to the works of Gerard Manley Hopkins, the parts that would tell me about all the misfit people she collected on her walks and the kids that everybody else had given up and she had decided to love. I give the axioms she penned back to her: “There are things to worry about and things to not worry about”; “There are no naughty children (there are only stories, and everyone’s got one) and no naughty dogs.” I tell her I too was an exception to the rule (i before e except after c—it seemed my mom and I were always following c).

There are other parts too that I’m glad are gone. (Can I say that? I said it.) The parts that told me that the best thing I ever did in my life was get married to my now ex-husband, the one she’s forgotten, that this was my greatest achievement. The part that would expect a female brand of duty out of me perhaps because it was what she had expected of herself. The part that didn’t get proper help for the anxiety and depression that punched it out within her. The part that once did a deep dive into herself and never came out.

My mom has two stuffed animals at Paradise Manor. They are called Shitface and Arsehole. They came into her life when she was in hospital one of the times and then she liked to cuddle them then. Now, they mostly sit on her shelf. She seems pissed off with them. Some days in the hospital, she would tell me that their names were Sweetie and Darling. The next day, they were Shitface and Arsehole again.

Relationships are like that, I suppose.

The Road to Paradise

We had a caravan that my dad would park at Happy Wanderers so that we didn’t have to tow it the five or so hours back and forth from Johannesburg.

I remember. I remember Happy Wanderers because this is what we were, weren’t we?

There was an old man called Madala (which I think wasn’t his name at all and rather a term of respect because he was old.) Madala used to take us on pony rides around the campsite at Happy Wanderers. I don’t know what any of this means.

I don’t want to remember my memories. I don’t know how to.

My heart feels empty. My heart feels empty. My heart feels empty.

References

Assal F. “History of Dementia.”Front Neurol Neurosci. 2019; 44: 118-126. doi: 10.1159/000494959. Epub 30 April 2019. PMID: 31220848.

Andress, David. Cultural Dementia: How the West has Lost its History, and Risks Losing Everything Else. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018. Kindle Edition.

Human Rights Watch. “‘This Government is Failing Me Too’: South Africa Compounds Legacy of Apartheid for Older People.” HRW.org. 27 June 2023.

Mvanyashe, Andiswa. “Umlungu: the Colourful History of a Word Used to Describe White People in South Africa.” The Conversation: August 7, 2023.

South African Government. “Older Persons Act 13 of 2006 | South African Government”: https://www.gov.za/documents/older-persons-act. Accessed: 30 October 2024.

South African Law Library, National Health Insurance Act, 2023, 16 May 2024. Accessed 20 December 2024: https://lawlibrary.org.za/akn/za/act/2023/20/eng@2024-05-16.

*

Deborah Vieyra is a South African-Canadian writer, teacher, and performer. The recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship, she holds an MA in Applied Theatre Arts from the University of Southern California and is currently completing an MA in Graduate Liberal Studies at Simon Fraser University. She’s got a thing for storytelling as a force for individual agency and social change — either you tell your story or your story will tell you — and is passionate about mentoring others to help them chase their tales.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster