‘Speak up and acknowledge’

Transforming Trauma Through Social Change: A Guide for Educators

by Theresa Southam, PhD

Santa Barbara, CA: Fielding University Press, 2024

$36.24 / 9798991258012

Reviewed by Lee Reid

*

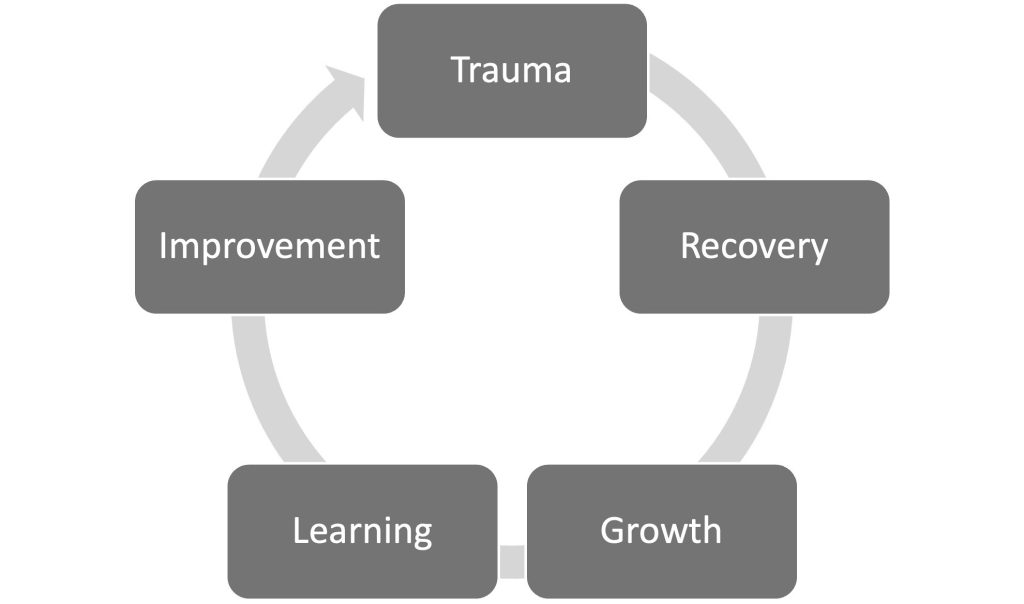

Transforming Trauma through Social Change is a nutrient-dense book of 330 pages. It deserves slow careful reading if you wish to secure a very rich education in becoming trauma-informed, through the cultural medium of storytelling. The book’s literary scaffolding is academic and therapeutic, inviting a growth mindset that encourages social and personal change in readers. “All of the case studies demonstrate the arc from trauma, to trauma acknowledgement, to critical reflection, to exploring new roles, to caring action.”

Who is the audience, you might wonder? ‘Transforming Trauma’ supports and informs educators, students, environmental advocates, teachers, historians, professors, sociolologists, counselors, virtually anyone in service to elder and younger generations, and to the earth. In contrast to the academic scaffolding, which many students and readers who enjoy evidence-based research, lesson prompts, charts, and numerous references will appreciate, the book unfolds a storytelling style that is fresh, personal, and intimate. In our multi-stress world, polarised by political and health care conflict, genocides, and wildfires, it serves almost anyone at any age to become trauma sensitive. I, as an elder, certainly am grateful for community-building maps such as this book. Theresa is one of many compassionate global trauma teachers who collaborate with Indigenous and Bipoc elders and educators. Some well-known influences on her work are international trauma leaders such as Gabor Maté and Thomas Hubl; indigenous author, botanist, and professor Robin Wall Kimmerer; mythologist and author Sharon Blackie PhD, and Buddhist mindfulness teacher Tara Brach.

Since the topic reflects daily traumas in our social, cultural, medical, and educational systems, you must at least be interested in digging below the sociocultural buzz in global newsfeeds. Theresa examines the values and stories of cultures and realities we might not otherwise have considered or understood. Are you ready for it?

Theresa Southam, the author, is a multidimensional woman who lives and works as a college administrator and teacher in the Kootenay community of Nelson, B.C. The book is evidence-based, loaded with far more teaching tools than your usual trauma research fare. It involves personal, culture-rich stories, indigenous and multicultural values, and years of the author’s hands-on relational work in education settings and classrooms. Transforming Trauma… is not easy light reading, but it is worthwhile to read, whether or not you are an educator. Seniors will find it helpful, especially if they feel called to service roles that offer guidance or compassion to others. This book represents one facet of critical relational work that teachers like Theresa are gifted at facilitating within the Kootenay’s Selkirk College setting. She is just as resilient and informed in indigenous settings, with ecology restoration and herbal healing, in ancient feminine lore, in literacy labs and curriculum planning, with conflict resolution, with walking the Spanish Camino de Santiago, and is a veteran in forging her unique feminist identity. Theresa is the mother of three young adult professionals who are trauma-informed, thanks to her.

Why I agreed to write a review is because, in essence, Transforming Trauma… is useful for educators and for humans who find our modern world challenging to navigate. Confessional here: Theresa has cast me in Chapter Five. Despite my squawking, I am one (of numerous) seniors in the book who represent aspects of ‘Ageism and Social Change.’ These folks are not ‘super seniors’ who energetically invest in the eternal youth and beauty industry, nor do they aspire to chronic busyness for a meaningful life, but they do challenge the status quo! For this review, I will offer a brief synopsis of the first three chapters, some points about the last two, and a summary. I am not trying to avoid chapter 5. Lame excuse: I simply ran out of space!

In her introduction, Theresa highlights five historic social movements which can provide classroom gateways to social reform. Those ‘change agent’ reform movements are: Land Back; Environmental; Peace; Multiculturalism; and Civil Rights. When she teaches or facilitates groups, she encourages students and teachers to ask ‘what social change movement is possible in your courses or programs?’ All five movements stem from trauma, and each has gained momentum to embrace or catalyse social change. How can we recognise them in action? Hint: our shared vulnerability as humans is the gateway. Grief, loss, disease, and pain, (which we each might recognise and relate to personally), are those familiar and inescapable gateway states.

The causes of trauma dramatically affect all communities, with disasters familiar to most of us: wildfires, wars, adverse childhood experiences (trauma), racial violence, genocides, etc. Most second and third generation immigrants carry versions of ancestral traumas from collective or enforced migrations, and political oppression. But Theresa’s approach is not complaining nor depressing. She offers concrete direction and lesson plans that support small collectives of activism and resistance. These she calls ‘cultures of resistance.’ If you treat yourself to the current biopic movie on Bob Dylan, you will see an enchanting example of what Theresa would call a ‘social imaginary’ or rebel who catalysed a musical revolution. Readers might be intrigued by the concept of ‘social imaginary’ and this is the first time I have heard the term. Like poets or artists and visionaries, “…they resist harmful societal narratives.” They reinvent and reimagine their social and cultural world. Theresa’s book offers practices and exercises designed to encourage the social imaginary minds of readers and learners. Unerringly, she connects readers to resources and activist movements that can reduce or heal trauma; and that equally support justice and social change. I will describe some in this review.

In Chapter 1 (Circles of Trauma and the De-extinction of the Sinixt People), we learn to recognise cultural and personal trauma. How? We become ‘trauma-informed’ by attuning to the signs and human symptoms of grief, loss, and bereavement; normal processes that we all experience. However, trauma casts a new light: “…there is a severe and lasting injury to the minds, bodies and souls of individuals and sometimes communities.” Trauma is “…a lasting harm that originates in a fundamental injustice.” What does Theresa mean by ‘fundamental injustice’? She means racism; the dehumanising of people by severing them from land, family, and culture. In ‘Transforming Trauma,’ indigenous advocates will applaud Theresa’s truthsaying work on de-colonising world views (i.e. racist prejudices) in academia, and international students will feel championed by her story of the injustices they face in Canada.

This first chapter teaches trauma-sensitivity through the story of Sinixt indigenous leader Virgil Seymour. He championed the ‘Land Back’ movement, and was a wise and generative man. Chapter 1 elaborates on the cultural and personal traumas caused by government betrayals. Treaty agreements were violated or rescinded, indigenous lands (which symbolised First Nations identity and sovereignty) were expropriated. By paying individuals a pittance for invaluable land, and then declaring the Sinixt to be extinct, a form of cultural genocide was sanctioned. Theresa frames the notoriously abusive residential schools as ‘workhouses’ or ‘sites of abuse and erasure.’ In ‘Transforming Trauma,’ strategies and measures designed to restore justice and emotional regulation are offered, with deference to indigenous sources. She also acknowledges the work of psychiatrist Judith Herman who was one of the first voices to assert that trauma is rooted in social and cultural causes. Herman highlights the moral and physical violence underlying culture-based trauma.

Virgil died young in 2016. His story, the story of restoring identity and hunting rights to the Sinixt nation in Colville, Washington, is an example of indigenous trauma stemming from colonisation. Actually, Virgil accomplished this work in stages, first by inviting Sinixt ‘aunties’ to cross the border to gather wild camas plants. In this story, which could similarly be applied to the traumatic incarcerations of the Doukhobor children, or the post-war internment of Japanese Canadians or of Ukrainians, trauma originates from government severing tribal connections to land and family. As well, spiritual rituals or faith in supernatural beings were amputated; banished were rituals that supported identity, autonomy, and belonging. In the least, this has caused moral injury, which is a nuanced and undiagnosable form of trauma (similar to PTSD) stemming from betrayal. One might consider the current U.S. tariffs as a form of moral injury…a betrayal of continuity of trust in relationships. Moral injury, shame and trauma transmit epigenetically down through the cultural DNAs of diverse generations. The more obvious symptoms of trauma that we see daily (or in media) are addictions, obesity and malnourishment, poverty, homelessness, random violence. Spousal abuse is another more visible form of moral injury, as are impoverished living conditions based on alarming social inequities. The cost to human health is enormous. “Adverse childhood experiences are the single greatest unaddressed public health threat facing our nation today,” writes Dr. Robert Block of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Often, the result is early human death, but that results from accumulated and transmitted cultural trauma. Theresa quotes Donna Jackson Nakazawa: “biography becomes your biology.” How true!

Our memories and accumulated life experiences live on through our nervous systems. This used to be called ‘your/our unconscious.’ The story of Virgil represents cultural trauma, but it also holds reconciliation and truth. Virgil himself felt that no one of any colour or culture should be excluded from healing and care, or the ability to forgive harm done to them. And, he participated in ‘Land Back’, a social movement that employed civil resistance to colonization by demanding that civil rights and stewardship be restored to their land. “Virgil befriended Doukhobors, whose ancestors had persecuted a Sinixt family. He saw everyone as connected.” Before Virgil’s time, reconciliation processes were initiated when a Doukhobor spokesman ultimately offered a poignant public apology on behalf of leader JJ Verigin, to Lawney Reyes and the Sinixt.

“Collective trauma is often the result of terrible experiences at a communal scale.” The Holocaust is another of the many examples of racial and cultural genocides, some of which continue today. As for the Sinixt, Virgil used wisdom, gratitude, kindness, and caring as his style of resistance in support of ‘Land Back.’ Essentially, he was saying: “We have never gone away…We can govern ourselves with our ancient systems on the land that we love and honour.”

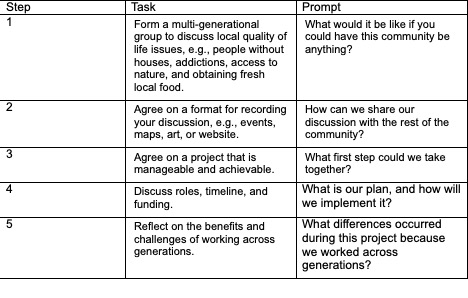

In Theresa’s book, we see reference to indigenous spirituality. We learn about the singers and the dreamers, the role of elders, the symbolic power animals in nature such as Orca or Eagle. She concludes this part with useful exercises for recognising and transforming trauma in schools and classrooms, all of which involve more reciprocal consultation with students. She recommends establishing a ‘literacy bank’ where students would be coached on the most efficient ways to glean information from a variety of sources including government, cultural, non-profits, and historic storytelling, language and lore. Wisdom (from, or taught by, elders) would be significant here.

Chapter 2 teaches us to speak up and acknowledge trauma. Essentially, to break down the codes of secrecy and silence that surround traumas. With people who fear abuse and persecution, who struggle to survive, how might we communicate with empathy and compassion? What are sensitive ways to address trauma? The chapter features Briony Penn, who championed activism against clear-cutting old growth forests on Saltspring Island. The issue the women rallied to protest was ‘Environmental Destruction.’

‘Transforming Trauma’ illustrates a format that Briony used called CITP which provides a chart for community recovery from trauma. Theresa explores the brilliant strategies the women invented and used, such as ‘barefoot mapping.’ She reveals how shared leadership evolved, and the protest strategies used by the women to effectively voice trauma. Examples of resistance were a nude calendar with community members posed in nature, culminating in a brave but risky ‘Lady Godiva’ ride on a horse in Downtown Vancouver. As Lady Godiva, Briony challenged the status quo of campus misogyny with her ride, which had a police escort. She confronted the UBC engineers who sponsored the annual Godiva ride tradition by presenting Godiva as a sex object. Her comment about the protest was, ‘When I get my PhD, nobody listens. I take off my clothes, and here you all are. Thank you, gentlemen. Now that I have your attention, I want to talk about endangered species and ecosystems. They have no protection.” The Saltspring women created trauma-reversing narratives such as “Salt Spring Island residents may be laid back, but they are dead serious about their trees.” Other groups in similar situations joined by bringing their own voices to environmental trauma. A forest trust on Cortes Island created a haunting wolf banner by artist Lisa Gibbons, with an equally poignant message: “Imagine…a forest in trust to the children.”

“Briony’s ride though the streets of Vancouver hearkens to a petition to stop corporate greed, and a reprieve for nature.” Post-trauma growth from Saltspring took the form of rich and increased collaboration with Indigenous groups. “Briony co-founded ‘The Land Conservancy of British Columbia’ which completed one of British Columbia’s first Land Back transfers by a land trust.”

‘Transforming Trauma’ confronts the polarised values of dominating ‘taker’ (extract and exploit) cultures, in contrast to ‘giver’ and ‘leaver’ eco-cultures. The latter are driven by multicultural values that aim to study, cherish, and become part of ecological systems. I appreciated Theresa’s allusions to the spiritual or mythic beings that diverse cultures call upon to protect the sacred in land. Lady Godiva was one historic person, but many cultures place faith in ‘well maidens’ or deities that protect water and wetlands, and other supernatural beings associated with plants and creatures.

CITP is also a program developed by the Pocket Project under Thomas Hubl’s global work with traumatised cultural groups. Like Briony Penn’s CITP program, Hubl follows similar ‘presencing’ principles such as 1) noticing, acknowledging and naming trauma, 2) witnessing emotional responses with compassion, deep inquiry, and deep listening, and 3) ritualising resistance through the lens of social change. Protests, story, artwork, theatre, festivals and films, social media and slogans, are some of the media used for resistance and social change.

The persecution of women through historic witch burnings is another example of epigenetic or cultural transmission of trauma. “There is a relationship between the feminine and nature,” Theresa writes “but for many of us that relationship is fraught with collective trauma. When someone calls me a witch, even playfully, I feel that trauma. To quiet that overwhelming fear, I connect with the beauty and quiet around me in my almost daily walks in nature…” What Transforming Trauma… offers is education into the historic violence and ‘othering’ (i.e. dehumanising) that underscores colonial systems of domination and extraction.

Transforming Trauma… honours the work of environmental activist Joanna Macy, now in her nineties. Macy’s ecology work, known as ‘The Great Unraveling,’ has, for decades, encouraged cultural exposure and ritualised expression of the grief inherent in traumas that harm our eco-systems.

In Chapter 3, ‘Peace’ is the change agent as we explore the values of redemption stories, or ‘wisdom stories.’ How do we make sense of trauma? How can we grow from it? For students who value peace or pacifism, how are they treated by more militant peers? Hint: we invite them to tell their stories.

For stories that heal and help, not only must there be a strong element of social connectedness, but these storytellers must also be motivated to contribute to the human condition. Their purpose is to benefit others, and not self-gratification. The Heroine’s Journey’ is one mythic example where a woman undergoes hardship (sacrifice or trauma) in order to strengthen or heal the community. ‘Generativity’ means that individuals contribute their accomplishments back into building community.

In the Kootenays, groups that were considered counterculture co-existed with the American Vietnam war protestors. For locals, the mix with immigrant cultures such as the Doukhobors, Quakers, Japanese Canadians, Chinese Canadians, was not always peaceful. All influenced and changed the systems around them. Each culture organised the lessons and growth from their traumas into resource or redemption stories that became legacies; legacies that nurtured the future and honoured the past. In turn, their stories encouraged a ‘learned resourcefulness’ that enabled the counter-culturists to become valued community members.

In Chapter 4 readers are asked: What are the new stories that emerge from trauma? For international students, (eerily similar to indigenous trauma from colonisation), the trauma is forced assimilation or ‘integration’ into white Canadian culture. What takes place under neocolonialism is erasure. Students’ values and cultural memories are ‘brushed aside’, diminished, or reduced to stereotypes. Sound familiar? Combined with exploitative treatment and abuse by landlords, or school/work systems that charge exorbitant fees, students quickly learn to present a false (or subservient) gratitude for meager concessions and low wage work. Consequently, they feel inadequate, burdened with stigma of possible failure. International students are often sexually abused, or are promised good jobs that do not materialise. They feel unable to speak out for fear of being discharged or deported. Typically, school/work systems impose their world views without consulting students about their own values and cultural traditions.

The change movement here is ‘Multiculturalism.’ Although some critics view multiculturalism as a token version of white integration, for our review’s purposes, multiculturalism differs from ‘integration.’ ‘Integration,’ as Theresa refers to it, pressures students to homogenise into white Canadian (i.e. neocolonial) values. Multiculturalism encourages diverse cultural perspectives, which are often shared through storytelling. “Trauma transformation can increase internal strength, lead to better relationships, uncover greater appreciation of life, and identify new paths.” Theresa exposes the micro-racisms implicit in higher education. “Racism is defined here as prejudice and discrimination towards a subordinate racial group by a dominant group, and justified by false notions of superiority.” Does anybody ever ask students what they need to thrive in a Canadian system? “Between 2013 and 2018, at least 15 international students studying in Canada committed suicide.”

Theresa follows this shocking news with the ‘success’ story of a South Asian student named Gangajeet Singh. Singh, a college class valedictorian, succeeded with achieving Canadian values, although his world view was often dismissed and disrespected. Theresa calls for education with more ‘intercultural competency,’ education that encourages a curious and adaptive approach to relationships. “The degree of cultural diversity in any group of humans directly relates to the degree of innovation, creative thinking, and problem-solving…” With neocolonialism, people are rewarded for effort with money; in multiculturalism, people tend to value enriched relationships and shared connections. “The opposite of the social grammar of destruction is the social grammar of co-creation where we see and sense each other.” Theresa offers a reflective exercise in the mindfulness practice of R.A.I.N. created by Buddhist teacher Tara Brach. Essentially, RAIN offers inner inquiry and a process of understanding and self-nurturing to repair trauma.

I, along with a myriad of creative seniors, are represented in Chapter 5. You, dear readers, could well be a ‘Chapter 5!’ In many quietly nurturing ways, seniors or elders can restore lost and broken connections among people. I claim to be completely ignorant about gardening, but endlessly in need of stories about culture, land, and lore. Whenever I need to gather community or stories, I will invent a change system or vehicle where people are encouraged to share their life-stories and accumulated wisdom. The garden tours are one example, along with an intergenerational school group, a food security greenhouse for seniors and youth, and face-to-face gatherings with seniors around the West Kootenay, where narrators could elicit and document their life stories. Whatever creation the project is, it invites transparent sharing and community-building. Yes, perhaps this is the style of the social or radical imaginary. “Radical imaginaries are ways of thinking about the world that pose profound departures from the dominant culture…they unmask unequal and unjust social norms.” Here, the trauma issue is ageism, and the social change is Civil Rights.

Theresa explores the tasks of quality aging (such as contemplation and stillness time, and generativity). She emphasises the need of seniors to remain relevant to their communities and family, when ageism creates more marginalisation, loneliness, and ‘the silent generation,’…an invisible population who sadly wait to die. She exposes polarity pitfalls such as the ‘super senior’ ideal of success where elders are expected to stay fit, independent, and autonomous, i.e. ideals that do not fit many seniors, and in fact keep them busy but isolated. Conversely, there is the compliant and often invisible silent senior who wants to be entertained and distracted. She examines the culture of ‘carelessness’ where programs for seniors are often created by younger people who seek obedience with the systemic rules, but do not consult personal needs of the elders. “Seniors hide their vulnerability behind stoicism or fake cheer, but suffer in silence.” Apparently, this is a quote by me!

Chapter 5 elaborates on five growth tasks for older adults (such as reviewing and changing one’s values and goals, or re-invigorating a shrinking social life). She applies the CARE manifesto model to projects that represent resistance to ageism. ‘Care’ aims to replace care-lessness or lack in our social systems. Examples of CARE are the gardening tours, or shared resources like vehicles and living spaces, or shared childcare, and neighbourly gestures of reciprocal care for homes and pets. CARE communities invest in caring kinship systems that bring all ages together. There are many exciting strategies to inspire creativity and community in Chapter 5. I will summarise with a quote that I suggest you apply to Transforming Trauma…

“…[Y]ou will find yourself resourcing from this book over the years to come. It is a wise investment. Why not give the future a relationship with YOU while you are here?”

*

A retired clinician, formerly with Nelson Mental Health, Lee Reid has written books about BC rural and coastal communities. Her stories centre around the values and health care needs of BC seniors. Lee has also written stories about intergenerational education, rural home support care , trauma, and dementia. Recently, she has written and self-published a fourth book: Stories of Mount Saint Francis Hospital: 1950-2005, which illustrates a legacy of compassionate nursing care in the West Kootenay. Her books are: From a Coastal Kitchen (Hancock House, 1980); Growing Home: The Legacy of Kootenay Elders (Nelson, 2016), reviewed by Duff Sutherland, and Growing Together: Conversations with Seniors and Youth (Nelson, 2018), reviewed by Luanne Armstrong. Visit her website here. [Editor’s note: Lee Reid has recently reviewed books by Ralph Milton, Gordon Wallace, Stefanie Green, Alison Acheson, Phyllis Dyson, and Joan Neehall for The British Columbia Review.] In 2018, she contributed a popular memoir of growing up in the south of England and North Saanich, The Spider Hunters. Lee is honoured to receive the Nelson 2024 ‘Citizen of the Year’ Award.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster