Alice Munro’s Tragedy of Secrets and Silence

by Holly Hendrigan

[Warning: This article contains details of abuse

and may affect those who have experienced

sexual violence or know someone affected by it.]

Alice Munro was not a character in an ancient Greek tragedy, but in her downfall, life imitates art.

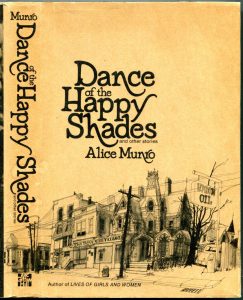

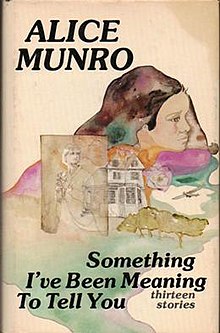

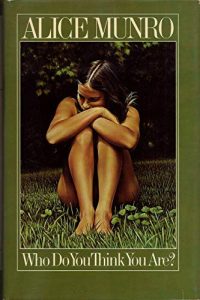

Born in 1931, the daughter of a Wingham, Ontario mink farmer, she was academically gifted from an early age. She married Bill Munro at twenty, moved to British Columbia, had three daughters, got divorced, moved back to Ontario, and married Gerald Fremlin in 1976. During her lifetime, she arguably became the best English language short story writer on the planet and won all the literary awards: the Governor General’s; Giller, and Booker prizes as well as the Nobel Prize for Literature. She is the subject of book-length biographies and hundreds of peer reviewed journal articles. She was beloved, and her public persona was that of a modest, kind, classy lady with a happy extended family. She died on May 13, 2024.

Two months later, her youngest daughter Andrea Robin Skinner published an article in the Toronto Star that completely changed the world’s perception of her mother and her short fiction (2024). Skinner wrote that Munro’s second husband sexually abused her when she was nine years old. She kept it a secret from her mother for seventeen years. When she told Munro in 1992, a family crisis ensued; Munro left Fremlin for a while, and he threatened to commit suicide. Ultimately, Munro chose to stay with him, and remained married to him until he died in 2013. Readers who idolized Munro are still reeling at the news that she did not leave the pedophile. Some threw her books in the garbage, and literature instructors are divided on whether to retain her works on their reading lists (Thompson, 2024; Pelz, 2024; Friesen & O’Kane, 2024). Globe and Mail arts reporter Marsha Lederman (2024) speaks for many when says her readers feel betrayed, because they trusted Munro through her insightful fiction. We cannot un-know her terrible secret. As Thomas King might say, Alice Munro’s story is now ours, and we distraught readers must “do with it what [we] will” (2008, p. 29).

To come to grips with this story, we could approach Munro’s trajectory through the lens of ancient Greek tragedies. This framework is not perfect: for example, Munro’s tragedy unfolds over five decades and concludes posthumously, whereas Ancient Greek tragedies such as Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, Sophocles’ Antigone, and Euripides’ Medea all take place over twenty-four hours. Still, it is possible to overlay Alice Munro’s story onto the structure that Aristotle developed in Poetics (1999), his short treatise of drama criticism written circa 345 BC. Munro was a member of an elite, an essential characteristic of a tragic hero. She also experienced three events that tragedies include: hamartia, peripeteia, and anagnorisis. Hamartia was her error in judgement; peripeteia, her reversal in fortune; anagnorisis, her (and her readers’) change from ignorance to knowledge. The great Greek playwrights brought these elements together, which allowed audiences to identify with the characters and feel pity and terror—catharsis—at their demise. We have all made mistakes, suffered consequences, and acknowledged our wrongdoing. Aristotle argues that watching an imitation of human weaknesses played out on stage—always with great suffering and violence—provides spectators with a release, a purgation of our emotions.

Why bother with Aristotle’s theories when considering Alice Munro, though? Real life and theatre are altogether different. When actual living people are involved, we lack the emotional separation we have when watching a play. Catharsis in the Alice Munro tragedy is limited and imperfect. But I hope that analyzing her life as though it were art will throw some light on us as fellow imperfect beings. Ancient Greek tragedies contain believable and fallible characters who wreak enormous destruction and suffering, and we exit the theatre with a better understanding of life’s messiness. Alice Munro’s story is a learning opportunity on unfathomable marriage dynamics, secrets, deference to power, and duplicity. It teaches us something about human nature, even as this tragedy provides limited, if any, emotional release.

Background on Greek Tragedies

Understanding Munro as a tragic figure requires some knowledge of Greek tragedies writ large. While an exhaustive summary of Poetics is beyond the scope of this essay, Aristotle’s definition of tragedy is worth quoting: “the imitation of an action that is serious, complete and substantial. It uses language enriched in different ways, each appropriate to the part [of the action]. It is drama [that is, showing people performing actions] and not narration. By evoking pity and terror, it brings about the purgation [catharsis] of these emotions”(1999, section 6). The three great Greek tragedians frequently mentioned in Poetics are are Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Most of their plays have been lost, but from the hundreds that were performed when the playwrights were living, thirty-two extant copies remain: seven each from Aeschylus and Sophocles, and eighteen from Euripides. Poetics provides Aristotle’s opinions on ‘best practices,’ and remains relevant today, as it is frequently cited in contemporary screenwriting manuals (Economopoulou, 2009). Aristotle was the first to codify the plot structure and character elements of Western storytelling, which involves hamartia, anagnorisis, and peripeteia.

Two Greek tragedies—Sophocles’ Oedipus the King and Aeschylus’ Agamemnon—clearly illustrate these plot elements. Most people are familiar with Oedipus Rex (ca. 427 BC), which unravels the backstory that explains why a plague has descended on the kingdom of Thebes. Twenty years earlier, an oracle told King Laius that he would die at the hand of his own son. To counteract this, Laius asked to have his infant son Oedipus abandoned on Mt. Cithaeron. The servant disobeyed Laius and offered him to Polybus and Merope of Corinth. As a young man, Oedipus learned that he was destined to kill his father and marry his mother. like his own father, he thought he could outsmart his fate, which illustrates his hamartia. He left his family home and did exactly what the Oracle had forecast: he killed a stranger who happened to be his father and unwittingly married his mother. During the play the men who facilitated his adoption admit what they did (anagnorisis), and Oedipus blinds himself, abdicates his throne, and exiles himself (peripeteia.)

Aeschylus’ Agamemnon more closely resembles Alice Munro’s story. Agamemnon is on his way home victorious from the ten-year Trojan War. People there are anxious, due to the circumstances of his departure, where he sacrificed his daughter in order to leave for Troy. The Chorus, voicing public sentiment, calls the slaughter of Iphigenia “reckless” (Aeschylus, l. 223), which signals Agamemnon’s hamartia. Shortly after he returns, his wife Clytemnestra, who never forgave him, stabs him to death in the bathtub (peripeteia). Agamemnon’s anagnorisis consists of two lines shouting out that he had been “struck a deadly blow” (lines 1342, 1345), recognizing the circumstances that caused his reversal of fortune.

Both Oedipus and Agamemnon are complex characters with flaws, which allows the audience to identify them and thus experience catharsis at the end of the play. Oedipus unwittingly kills his father and marries his mother, but his transgressions lead to a plague in Thebes that would end only after he left. The audience feels sympathy for him but also knows that incest and parricide warrant consequences, and he must abdicate his crown and live in exile. Agamemnon’s case is slightly different: he has a choice, and he prioritizes his military goals over his daughter’s life. Most parents can relate to the difficult balance between their careers and their parental responsibilities but would never kill their own child to go fight a war. Clytemnestra’s grief and fury is understandable, and contemporary audiences most likely believe that Agamemnon’s punishment fit his crime. Watching these plays surfaces pity and terror in the audience, and by the end, we can stand up in our seats and yell “Bravo!” at the spectacle, releasing the tension that built up during the performance.

Hamartia, Peripeteia, and Anagnorisis in the Alice Munro Tragedy

Nobody is clapping at Alice Munro’s demise, but mapping Aristotle’s theory of tragedy to Munro’s life remains a worthwhile exercise. It begins with identifying her hamartia. As classicist Kenneth McLeish describes it, hamartia is a tear in the universal order, which includes errors in judgement as well as “wilfully taking any course which you knew to be wrong” (as quoted in Aristotle, 1999, p. xi). Agamemnon, for instance, knows that killing Iphigenia is morally wrong. Two pivotal instances of hamartia set off Munro’s tragedy: first, her marriage to Gerald Fremlin, who turned out to be a temperamental, controlling pedophile. There were early indications that he was troubled: in 1978 friends told Alice Munro that he exposed himself to their daughter (Skinner, 2024). More importantly, though, her decision to stay with him after learning what he did to Skinner crossed a hard line of parental duty and care.

Munro’s peripeteia, or reversal of fortune, is linked to her hamartia. In Greek tragedies, the reversal is staged within the confines of the play, but in this case, it occurred decades later, when Andrea Skinner published her article in the Toronto Star. Alice Munro fans, who unwaveringly support Skinner, reacted to the news with shock and outrage. In Greek tragedies, peripeteia involves physical violence or exile; in Munro’s tragedy, peripeteia involves her tarnished reputation. What a reversal from May 2024, when her obituaries were full of praise and love. Anthony De Palma (2024) declared in the New York Times that her stories were “without equal,” and novelist Richard Ford proclaimed that her writing was “as good as it gets.” De Palma’s obituary also mentions Munro’s tendency to avoid publicity. Two months later, the public discovered why Munro avoided having in-depth conversations with journalists.

Posthumously, Munro has joined a club of controversial artists that have been labeled “art monsters”: creators of groundbreaking art whose personal lives disrupt our appreciation of their art (Dederer, 2017). This club includes Pablo Picasso, Ezra Pound, and Woody Allen. Picasso treated the women in his life badly, driving some to suicide (Delistraty, 2017); Ezra Pound supported fascist dictator Benito Mussolini and broadcast antisemitic messages during World War Two (Kindley, 2018); Woody Allen married his adopted daughter, his junior by thirty-five years (Fragoso, 2015). We make personal choices that determine the extent of this disruption: many people put these mens’ biographical details aside and visit the Picasso Museum in Barcelona, appreciate and study Pound’s Imagist poetry, and buy a ticket to watch Allen’s Annie Hall in a repertory theatre. But others say ‘nope’ and avoid them, exercising their intellectual freedom to choose what art they see, read, and watch. Of course, cultural gatekeepers also play a role in determining the legacy of controversial artists. English literature departments and individual instructors will decide whether Alice Munro remains on reading lists in English classes, and publishers will assess whether there is a market for keeping her books in print. Are any filmmakers or playwrights currently interested in adapting her stories, as was the case with Sarah Polley’s Oscar-nominated film Away from Her? It is too soon to tell.

Many people, including Alice Munro’s own children, firmly believe that she belongs in the canon of Canadian literature, despite her decision to remain married to the man who sexually abused her daughter (Dundas and Powell, 2024a; Stratton, 2024). At the time of writing this essay, most of the reliable sources of information on the topic were written by Munro’s adult children or journalists and published in the news media. In the years to come, we can expect scholars and literary biographers to take a closer look at Munro’s personal life in relation to her literary works. Stories such as “Runaway,” which deals with mother-daughter estrangement, and “Vandals,” where a couple commits property damage to a man who sexually abused them, are, clearly, not entirely fictional. Where peripeteia in Greek tragedies is well-defined, the extent of Munro’s peripeteia is less clear, but we know it is substantial.

Anagnorisis, or discovery, is the most complicated and layered of the three elements, evolving over fifty years. It first occurred in 1976 when Skinner told her father, stepmother, and stepbrother what Fremlin did to her that summer. Jim Munro insisted that everybody shut up about it. As Margaret Atwood says, “they were from a generation and place that shoveled things under the carpet” (Alter et al., 2014). After learning the truth in the early 1990s, Skinner and Munro became estranged, especially after Skinner had children in 2002 and refused to let Fremlin near them. Two years later, Munro lied, telling New York Times reporter Daphne Merkin (2004) that she was close to all her daughters. This statement made Skinner so angry that she went to the police with proof of Fremlin’s abuse. When the police came to inform Fremlin that he was being charged, Munro told the police that Skinner was lying (Powell and Dundas, 2024b). Yet in March 2005, Fremlin pleaded guilty of indecent assault. Skinner managed to create a public record that refuted her mother’s gaslighting.

Munro knew that she should have left Fremlin in 1992; she also knew that her reputation would suffer if people knew the truth. She told her biographer Robert Thacker, “That would become what people would know. I worked for a long time to be who I am” (Aviv, 2024). Still, Thacker reports that Munro’s estrangement from Skinner was “one of the saddest things in her life” (Alter et al., 2024). In 2008, Munro felt that her daughter wanted to inflict suffering on others. Several years later, however, her perspective on her family relationships changed. By 2011, Munro began having issues with her memory, which eventually developed into Alzheimer’s Disease. After Fremlin died in 2013, Munro said, “I do not wish to be buried next to that man” and “It was beastly of me not to get rid of him” (Aviv, 2024). Munro’s anagnorisis was private rather than public.

By contrast, Agamemnon’s anagnorisis is public: everyone in the country knows what he did to appease Artemis. In “The Sacrifice of Iphigenia,” Agamemnon is shown on the left, hooded, looking away, while his daughter is carried away for sacrifice. His shame and guilt match Munro’s. Still, like Munro, he set these feelings aside while he got on with career. He even expected to resume his marriage after the war, but his wife Clytemnestra had other ideas. Gerald Fremlin also acknowledged, to Sheila Munro, that he was wrong to have abused her sister: he said, “it’s terrible, what I did to my family” (Aviv, 2024). He continued with his marriage and his intellectual pursuits for the rest of his life and was not outed until after Munro died.

As in Greek tragedies, with Alice Munro, the truth and their consequences eventually prevailed. In the ensuing deluge of media stories, we learned that Douglas Gibson, Munro’s publisher at McClelland & Stewart, and Robert Thacker both knew, and remained silent (Alter et al, 2024). Indeed, it was an open secret, echoing the title of Munro’s collection of stories published in 1995. Margaret Atwood and Jane Urquart found out after Munro won the Nobel Prize in 2013. Carole Sabiston, Skinner’s stepmother, claims that “[e]verybody knew” (Dundas and Powell, 2024a). A journalist once asked her at a dinner party if the rumours were true, and she answered yes. To say that “everybody knew” is an exaggeration, but the story seems to have been widely known in certain Canadian literary circles, and news outlets ignored Skinner’s emails telling them of Fremlin’s conviction (Dundas and Powell, 2024b).

Understanding Catharsis

Alice Munro’s story roughly follows the pattern of an Ancient Greek tragedy, with a unique blend of hamartia, peripeteia, and anagnorisis. But what does catharsis—pity and terror—look like? In tragedies, we project ourselves onto the characters and suffer, and learn, alongside them. Aristotle argues that we enjoy tragedies because they result in a feeling of “pleasure” that is “peculiar to tragedy” (1965). In fact, McLeish’s translation indicates that feeling pity and terror is satisfying (1999). In the Alice Munro tragedy, we may recognize and relate to themes such as family secrets and family estrangement. Munro’s decision to stay with Fremlin turns out to be a sadly common phenomenon, and, to a lesser or greater degree, some of us may have also disappointed or even betrayed someone in order to further our own ambitions. Munro’s tragedy also exposes the propensity to close ranks to protect someone who is a literary celebrity, a family member, or a close friend. Finally, we understand that, like Munro, our public personas differ from our private selves, having learned that a successful and seemingly well-adjusted Canadian writer tamped down a shocking and violent secret. If you used to think that, unlike you, Munro lived a perfect life, we found out in July that her family life was anything but.

Delving more deeply into catharsis in the Alice Munro tragedy involves uncovering some painful truths. First, experts in child abuse were not surprised when the truth about Fremlin, Munro, and Skinner came out (Ireton, 2024). Many women stay with men who harm their children. Indeed, Skinner’s stepbrother Andrew Sabiston calls their story “a textbook case of [how] families deal with sexual abuse” (Dundas and Powel, 2024a). Sam Lazarevich, the detective who collected evidence of Fremlin’s crime, agrees, speculating that it happens out of love, fear, or dependency (Powell and Dundas, 2024). Munro’s friend Vera Steffler believes it came down to money and security: Munro was living in Fremlin’s house and claims she did not become wealthy until she won the Nobel Prize (Baleeiro, 2024). Munro herself resisted the “misogynistic culture” that expected her to sacrifice her own needs for her children (Skinner, 2024). As Steffler puts it, Munro was simply “looking out for herself at that stage of the game” (Baleeiro, 2024). She did not drive and needed Fremlin as a chauffeur. Clearly, there are many reasons why women stay in troubled relationships; the sad point of this tragedy is that it happens more often than we would like to believe.

As we reflect on what catharsis looks like with Alice Munro, it’s fair to ask whether her story reflects her generation’s values. I disagree. Even two generations ago, parents protected their children from pedophiles as best they could. In 1969, when Jane Morrey was nine years old, she reported to her mother that Fremlin, a family friend at the time, exposed himself to her. Morrey’s mother kicked him out of their house and broke off their friendship (Forrest, 2024). Verna Steffler, a contemporary of Munro’s, disagreed with Munro’s decision to stay with Fremlin (Baleeiro, 2024). While sexual abuse might be more openly talked about now than it was in the 1970s, even then, abusers were shunned if not criminally charged.

While people believed young Andrea Skinner when she told them what happened, nobody seemed to think it warranted exposure. Skinner’s father Jim Munro, once a beloved Victoria bookseller and Order of Canada recipient, sacrificed his relationship with his own daughter to protect Alice (J. Munro, 2024). Sheila Munro, Andrea’s older sister, published a 272-page biography of their mother that barely mentions Andrea and certainly does not mention what Fremlin did to her (S. Munro, 2001). In 2005, Skinner provided Robert Thacker with evidence of Fremlin’s crimes, and he refused to include it in his biography, claiming that it was “a private family matter” (Alter et al., 2024). At least one journalist in Carol Sebaston’s orbit refused to report on it. When journalist Sandra Martin began writing a story on Fremlin’s court case, her employer The Globe and Mail refused to publish it (Aviv, 2024). While the secret keepers did not all know each other, this story has the makings of a conspiracy of silence.

Munro’s tragedy thus reveals how reluctant we are to challenge literary celebrities. Maybe people simply wanted to believe the image that Munro projected, whether they knew the truth or not. Douglas Gibson may have known that outing Munro put McClelland & Stewart’s financial interests at risk. Munro’s personal friends undoubtedly wanted to protect her from scandal. But the fact remains that professional biographers and journalists have an ethical duty to report truthful information that is in the public interest, and their silence was appalling.

Finally, we have learned that we human beings are flawed, inconsistent, and make mistakes. As Walt Whitman (1892) put it: “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself, / (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” We were wrong to assume that someone who wrote so perceptively about human relationships would never betray her own daughter. Atwood, a friend of Munro’s for decades, remarked, “You realize you didn’t know who you thought you knew” (Alter et al., 2024). Munro wore the persona of a kind and generous person very well. Jonathan Franzen, for one, was misled by her dust jacket photos, where she was “smiling pleasantly, as if the reader were a friend, rather than wearing the kind of woeful scowl that signifies really serious literary intent” (2004). However, she probably inhabited that personality much of the time: as her daughter Jenny stated, “She was warm and delightful and had a loving kind of personality. I was devoted to her. It’s very complex” (Dundas and Powell, 2024a). Still, Jenny and the rest of her family also knew that Munro turned a blind eye to her husband’s crimes against her youngest daughter. While it is easy and convenient to provide someone with a single label, be it Good or Terrible Person, Munro proves the opposite is true. Aristotle would nod approvingly at viewing her as a tragic hero, as hamartia cannot occur in people who are innately wicked.

However, the fact that Alice Munro and her family are not fictional characters weakens our experience of catharsis. When we watch Agamemnon we appreciate the complex situation on the stage and feel pity and terror for the characters, but we also know that Iphigenia wasn’t real, and that the actor playing Agamemnon bleeds fake blood into the bathtub and when the play is over he will remove his makeup and get in his car and drive home. But Andrea Skinner is real, and so was her self-serving troika of parents who caused her such harm: Alice and Jim Munro, and Gerald Fremlin. Skinner and her siblings have to deal with their shame and complicated feelings for the rest of their lives. At the end of this tragedy, I don’t feel purged—I’m still processing my catharsis and listening to Thomas King telling me that it’s my responsibility now to do something with this story. At best, then, catharsis in the Alice Munro tragedy involves what we allow ourselves to learn from it. Di Brandt (2024) advises us to face the truths that she hid, and do better, because they will not disappear by looking away, discarding her books, or refusing to read her.

Applying Aristotle’s framework of hamartia, peripeteia, anagnorisis, and catharsis situates Munro within a context of notable characters who made a terrible mess of their lives and that of their loved ones. Alice Munro, her family, and the Establishment of Canadian literature forced Andrea Skinner to “live a lie” to project a fictional version of the famous writer (J. Munro, 2024). This deception was a wound that hurt the entire family, and it did not begin to heal until they acknowledged what happened. Viewing this story through the lens of tragedy demonstrates that their actions and reactions were, sadly, not entirely remarkable. But there is room to grow: as Andrea Skinner remarked (2024), “I want so much for my personal story to focus on patterns of silencing, the tendency to do that in families and societies.” Her family tragedy is an object lesson in the destructive force of silence. We could all reflect on points in our lives when we have chosen to say nothing or speak up and ask ourselves who suffered from our silence.

Bibliography

Alter, A., Harris, E. A., & Isai, V. (2024, July 9). A Silence Is Shattered, and So Are Many Fans of Alice Munro. The New York Times.

Aristotle. (1965). Poetics, section 1453b (R. Kassel, Trans.). Perseus Digital Library. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0056%3Asection%3D1453b

Aristotle. (1999). Poetics (K. McLeish, Trans.). Nick Hern Books.

Aviv, R. (2024, December 23). Alice Munro’s Passive Voice. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/12/30/alice-munros-passive-voice

Baleeiro, B. (2024, July 9). In Alice Munro’s hometown, an exposed family secret stuns fans, friends. London Free Press.

Brandt, D. (2024, August 17). Munro’s coverup themes seen in new light. Winnipeg Free Press, C1.

Dederer, C. (2017, November 20). What Do We Do with the Art of Monstrous Men? The Paris Review. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/11/20/art-monstrous-men/

Delistraty, C. (2017, November 9). How Picasso Bled the Women in His Life for Art. The Paris Review. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2017/11/09/how-picasso-bled-the-women-in-his-life-for-art/

DePalma, A. (2024, May 14). Alice Munro, Nobel Laureate and Master of the Short Story, Dies at 92. The New York Times.

Dundas, D., & Powell, B. (2024a, July 7). A conspiracy of silence: To protect their mother, Alice Munro’s children kept a secret. Now, they want the world to know. Toronto Star, A.3.

Dundas, D., & Powell, B. (2024b, July 16). A “family matter”: How the story of Alice Munro’s daughter could stay hidden for so long. Toronto Star, A.8.

Economopoulou, K. (2009). Aristotle’s Poetics in Relation to the Narrative Structure of the Screenplay [M. Phil, Nottingham Trent University]. https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/64/1/203971_Karmela%20Economopoulou%20Dissertation.pdf

Forrest, M. (2024, August 8). Second alleged victim of Alice Munro’s husband says parents must protect their kids. Waterloo Region Record, A.5.

Fragoso, S. (2015, July 29). At 79, Woody Allen Says There’s Still Time To Do His Best Work. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2015/07/29/426827865/at-79-woody-allen-says-theres-still-time-to-do-his-best-work

Franzen, J. (2004, November 14). “Runaway”: Alice’s Wonderland. The New York Times.

Friesen, J., & O’Kane, J. (2024, July 11). Academics grapple with how to teach Alice Munro’s work in wake of daughter’s sexual assault revelations. The Globe and Mail, A14.

Ireton, J. (2024, July 22). Alice Munro stood by her man. She’s not the only one. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/alice-munro-stood-by-her-man-she-s-not-the-only-one-1.7267722

Kindley, E. (2018, April 23). Coming to Terms With Ezra Pound’s Politics. The Nation.

King, T. (2008). The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative (3rd ed.). University Of Minnesota Press.

Lederman, M. (2024, July 9). Alice Munro betrayed us, and her own legacy. The Globe and Mail, A11.

Merkin, D. (2004, October 24). Northern Exposures. The New York Times.

Munro, J. (2024, July 13). I didn’t tell my mom. It was a giant mistake. Toronto Star, A.15.

Munro, S. (2001). Lives of mothers & daughters: Growing up with Alice Munro. McClelland & Stewart.

Pelz, B. (2024, July 25). Teaching Alice Munro. The Mookse and the Gripes. https://mookseandgripes.com/reviews/2024/07/25/teaching-alice-munro/

Powell, B., & Dundas, D. (2024, July 12). Munro accused daughter of lying. Toronto Star, A.1.

Skinner, A. R. (2024, July 7). My mother was famous for her stories. This one is mine: My stepfather sexually abused me as a child. When I finally told my mother, she broke my heart. Toronto Star, A.2.

Stratton, A. (2024, July 12). In defence of Munro’s legacy. National Post, A.9.

Thompson, N. (2024, July 10). Academics re-evaluating how to teach Munro’s work after daughter’s abuse revelations. Victoria Times Colonist.

Whitman, W. (1892). Song of Myself. Poets.Org. https://poets.org/poem/song-myself-51

*

Holly is a member of the 2022 GLS cohort, and has an old-timey Honours English Literature degree from UBC. She lives in East Vancouver, and worked for years and years as a public and academic librarian.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “Alice Munro’s Tragedy of Secrets and Silence”

A fascinating take on what is a tragic story in the Greek sense as the author makes clear. My “forgivenesss” for Munro is immaterial but it won’t be given. I regard the canon of her work with distaste and will never read the works again. She was a Narcissist who ultimately betrayed her daughter.

Holly,

Thank you for this brilliant and thoughtful discussion.

Your choice to compare Munro to the Greek tragic hero is both startling and appropriate.

Munro did not belong merely to the elite. As a Nobelist, she belonged to the elite of the elite.

And her betrayals were not commonplace. Munro’s betrayals were epic. Not only did she betray her daughters, she also betrayed her readers.

Munro used her later writing as a complex apologia. Readers would read her stories embedded with her knowledge and psychological analysis of pedophilia before they knew about her husband’s pedophilia. World wide, readers were enlisted, just the way her first husband, her acquaintances, her publishers, her biographer, the local press and the local judge were enlisted. There is an epic nature to the betrayals.

Your choice of Agamemnon as the best comparison to Munro provides a terrible and important shock of recognition. I appreciate your careful, thoughtful work in this essay very much.

I still believe that college courses on Munro should be team taught by literature and psychology. But in addition to Andrea Skinner’s essential Toronto Star essay of July 7, 2024, your essay should be added to the reading list.

One thing: yes, Munro is a “tragic” hero. But the real hero here is not Munro. The real hero is Andrea.