Emerging from medical training

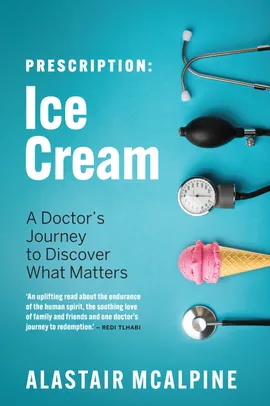

Prescription: Ice Cream: A Doctor’s Journey to Discover What Matters

by Alastair McAlpine

Johannesburg: Pan MacMillan South Africa, 2024

$37.50 / 9781770108042

Reviewed by Jessica Poon

*

Alastair McAlpine is not only a paediatric infectious disease physician, but also an unusually talented memoirist. McAlpine’s memoir, Prescription: Ice Cream, is everything you want in a memoir—immediately immersive, frequently funny, wincingly candid, and more often than not, genuinely profound.

The first section enumerates his travails and foibles during McAlpine’s medical internship at Bara, short for Baragwanath Hospital, a hospital notorious for an exceedingly high-pressure environment—even for a hospital. Or, in McAlpine’s words: “Those who had survived their internship at Baragwanath wore it like a badge of honour and had the grizzled, slightly damaged look of war veterans who had ‘seen things’, rather than junior professionals with a two-year medical apprenticeship under their belts.” McAlpine, lacking confidence and green as can be, initially struggles; however, he also consistently creates rapport with his patients and remembers their names.

When McAlpine’s mentoring physician, Chloe, instructs him to grab as many forms as he can, McAlpine sensibly asks why more forms aren’t printed—after all, if they were always available, there’d be no need to pre-emptively stock up. But obvious-sounding solutions have a way of being dead on arrival. Sometimes systems are resolutely broken and show no amenability to solutions, which means learning how to succeed in a dysfunctional environment—rather than trying to fix it—becomes an essential skill. When Chloe advises him on how to request tests for his patients in the overworked hospital, she says: “To get your requests approved in this place you sometimes need to ‘massage’ the truth a little bit.” For instance, mention you didn’t see a patient’s eyes move—because they were asleep. It’s the truth, but with an intentionally alarming implication that isn’t truthful for the good of a patient, vying with other patients with similarly compelling reasons and “massaged” truths.

McAlpine is idealistic and keen to learn. Easily overwhelmed, he recognizes that: “Each one was sick. Each one was in pain or distress. Trying to treat them as individuals when they all merged into one amorphous blur became increasingly difficult.”

“The only enthusiasm he seemed to show was during the ravenous inhalations of the cigarettes that he chain-smoked at all hours.”

When it comes to romance, McAlpine can’t quite decide between two women, ultimately ending up with neither. On a night out with is fellow interning doctors, he volunteers to be their designated driver and later reveals that he is an alcoholic with a major sweet tooth—namely, ice cream. Especially Magnums.

In the second section, the reader learns how McAlpine became dependent on alcohol I found myself fervently underlining this passage:

My self-worth at the time was built around ‘being smart’ and since I was in no way physically imposing, it was my only armour against the cruel jibes of adolescence.

… Since my identity was carved and moulded around my brain’s ability to out-think any of life’s problems, it simply never occurred to me what might happen when the problem was my brain. And what might happen when I could no longer rely on it to get me out of a tricky predicament.

I’m reminded of a rather terrible movie, which I won’t name here, where the principal’s concise advice for raising girls went something like this: “If they’re smart, tell them they’re pretty. If they’re pretty, tell them they’re smart.” The crudeness of the falsely invoked dichotomy, nevertheless, does indicate an intimate familiarity with just how irritatingly popular this false dichotomy is. If the propaganda machine classifies people based on their looks or intelligence—ignoring the obscenely fortunate people who are practically drowning in a veritable surplus of recognizably desirable traits—then, to have the one iron-clad thing you find solace in—your intelligence—reveal itself as terrifyingly precarious, not a guarantor of anything, a crisis of confidence is inevitable. It’s humbling in the worst possible way. If your highly prized, easily recognized intelligence is, like most things, liable to occasional faultiness, where does that leave your identity?

McAlpine also explains how people without addiction histories often lack a nuanced understanding. He explains the insidiousness of increased substance dependency deftly:

Addiction is an exercise in constantly adjusting the invisible line of acceptability. People say, ‘I could never drink neat vodka on my own,’ but they don’t realise that people with alcoholism don’t jump from social drinking to mixing whisky with their cornflakes overnight. Addiction, rather, is a process that goes at different speeds and in different increments for different people. You find a marker and repeatedly tell yourself and others that you will go this far and no further. But soon you find yourself nudging that line again and again until eventually simply cross it and move it to anew position. … the insanity of having an internal debate about whether it was normal to be holding out till am to have a drink simply didn’t register. The line had shifted imperceptibly until it had vanished altogether.

McAlpine simultaneously acknowledges and, with regards to himself, disavows the stereotypes that beset many people’s conception of an addict:

The trope of the damaged human, broken by life and circumstance, seeking solace in mind-altering chemicals is one that is deeply embedded in the common psyche. We understand and sympathise with this image. Who, on the other hand, would feel anything for the high-flying, wealthy white kid who drank excessively because … well … because of no reason that made sense? I definitely wouldn’t show any mercy to such weakness. I’d tell him what a miserable waste he was; that he should get his shit together immediately. Thinking about it just made me angrier and more perplexed.

There is nothing like meta-feelings—feelings about your feelings, in addition to the feelings themselves—to constitute the world’s worst cherry on top. If you’re constantly berating yourself for imperfections “unworthy” of your social standing, you’re not exactly on the road to recovery, which I’m told, time and time again by various white therapists, is paved with self-compassion.

When McAlpine is in rehab, his real, unvoiced desire is as follows: “How could I tell them that what I really wanted was to learn to drink successfully?” (This made me laugh out loud wryly).

A fellow rehab patient hooks McAlpine onto metal music, which ends up being surprisingly beneficial to a hostile, noncompliant teenage patient of his for a satisfyingly full circle moment. Of the polarizing music genre, McAlpine writes:

Metal! Where others found the cacophony stroke-inducing, I found it soothing and focusing, like an all-consuming, protective blanket flung over my smouldering mind, extinguishing the overheated anxieties and fears.

… Put simply, the vocalists were screaming so that I didn’t have to. The music was furious so I didn’t have to be. It destroyed things so that I could keep them intact.

I couldn’t have worded it better myself.

As a dog owner myself, I appreciate McAlpine’s acute understanding of how important pets are to their patients of all ages.

During one ward round, I presented Mr. Peterson, who was extremely close to his dog, a Labrador named Chuc. I mentioned to the consultant that the patient wasn’t sleeping at night because he was worried that Chuck was lonely in his absence. There was an awkward silence before I heard some coughing and stifled laughter. … While the anxiety persisted, Mr Peterson’s illness proved refractory to everything we tried. In desperation, I contacted his trusted neighbour who agreed to look after Chuck, take him in, and make sure he was fed and loved. I relayed this to Mr Peterson and instantly I could see the anxiety flow out of him like pus being drained from an abscess. His inflammation subsequently settled. The consultant took the credit because of the introduction of a fancy new medication, and maybe that did the trick, but I now make sure to ask every patient the names of their pets and who’s looking after them.

As McAlpine continues to grapple with his desire to drink, with his determination to become a doctor—a job beset with relapse possibilities in seemingly every possible way—he finds himself unexpectedly attracted to palliative medicine in paediatrics. McAlpine wonders how essential suffering is to living. Over time, he sees that desperately trying to prolong a life—which will end soon regardless—at the expense of the patient’s longing to see their family or their dog in a non-hospital setting—might not actually be the kinder thing. He observes that children who are going to die soon are far less neurotic about social media, if indeed they use it at all. They, perhaps by dint of being so close to death, know what’s most important in life—and it’s definitely not Instagram followers or the opinions of people they don’t even like. Who cares about collecting mindless likes from insipid nonentities when you’re going to die? With the permission of his young patients, McAlpine shares their insights on Twitter, which become briefly viral.

McAlpine’s memoir is a cogent, salubrious reminder that our accolades and impressive achievements are, more often than not, seldom the reason why anyone likes or trusts us. Initially, McAlpine keeps his recovery and his doctorly life neatly compartmentalized. He observes that:

Mental illness – and addiction in particular – were not spoken about publicly in the medical field. Any hint of an impediment could go on your record and follow you for the rest of your days, limiting career prospects and even registration with licensing bodies. Best to keep your problems to yourself.

Later, McAlpine decides to drop the façade of perfect professionalism. As it turns out, letting down our guard in favour of vulnerability—the parts we so desperately try to conceal with competence and emotional unflappability—are precisely what garners other people’s trust, a mutually beneficial enterprise.

Prescription: Ice Cream is a superb memoir. It is not tritely sanguine, but rather, emotionally earnest, often funny, and full of retrospective wisdom and bracing self-awareness. Plus, there’s an unforgettable anecdote involving a truly unhygienic jelly baby candy that makes me cackle inside just thinking about it. Though McAlpine humbly mentions he doesn’t know the key to happiness in the end, I think he does. After reading it, I thought about my life differently—and for longer than a millisecond, too.

*

Originally from East Vancouver, Jessica Poon is a writer, former line cook, and pianist of dubious merit who recently returned to BC after completing a MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph. [Editor’s note: Jessica Poon interviewed Sheung-King, and recently reviewed books by Jack Wang, Bal Khabra, Christopher Cheung, Anne Hawk, Pat Dobie, and Giana Darling for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “Emerging from medical training”

Such a good and comprehensive review!