Music’s power and magic

The Three Sisters

by Paul Yee (illustrated by Shaoli Wang)

Vancouver: Tradewind Books, 2024

$24.95 / 9781990598265

Reviewed by Alison Acheson

*

The Three Sisters, a picture book, is Paul Yee’s tenth work with Tradewind Books, including short fiction for teens and the Shu-Li series. Shaoli Wang has illustrated most of these books for younger children.

Yee (Bamboo) has been the recipient of the Governor General’s prize and others. The jury’s citation for the Vicky Metcalf award of 2012 notes that his works “stand as classics” and that Yee is “virtually the first children’s author to document the Chinese Canadian experience from its early days to the present.”

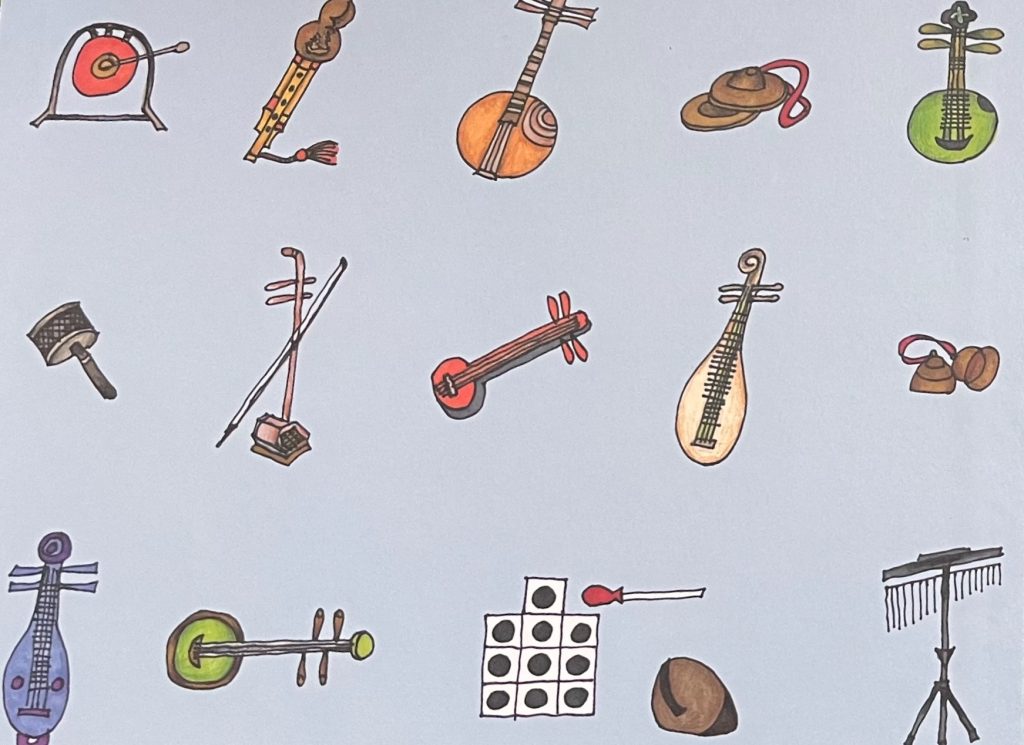

The drawings on the end-papers—what holds the guts of a picture book to its cover—can be a treat, and in The Three Sisters don’t disappoint, with no less than thirty musical instruments illustrated. A young reader could peruse and try to name or guess at the instruments—a wonderful introduction to the theme of music, as well as musical culture—and to ponder similarities and differences world over. What is a flute? What is a drum? A stringed instrument? Altogether a magical beginning and close to an original folktale.

As with any folktale, even an original, there are recognizable motifs and tropes, the number “three” being an example. In so many folk and fairy tales there are three brothers; let the three sisters play on!

On the first page is Emperor Wang with his red and orange clothing, who believes that the only alternative to not being a coward is to be a fighter; he is a simplistic and ignorant man. His advisors want peace, and he wants none of it. In the cloud of his thought bubble we see warriors warring.

The only thing that soothes this emperor is music. A couple, wife and husband, are the court musicians. They have three daughters who practice their own music out in the garden; in the garden the colours are purple and green—verdant, calming, and imperial.

The emperor demands that the daughters play for him, even though their father says they are not yet ready.

This is when the story gets interesting! The reader will have to consider and possibly discuss: are the daughters really not ready? Is their father being too protective? Or is he wanting not to give in to the demanding and selfish emperor?

The father pays a price for standing up to this nasty man; he is sent off far away to do military duty, to play music for the troops.

Before he goes, he shares his musical wisdom with his daughters. This wisdom is later recalled and considered by each daughter when it’s her turn to perform for the emperor.

But the bullying of the emperor continues. The daughters, one by one—in the tradition of such stories—must play music for him. And one by one, with those words of their father in their minds, magical things happen. In the end, they make an escape, and the emperor is brought—literally—to his knees to call for peace.

Here again, the story grows doubly interesting and might elicit good questions from the readers: is it enough that the emperor seems to change because of the fear he feels? Is it useful that he feels fear? The story says that it’s at “the sight of such magic” that he changes. But is that enough? Does he need to feel the magic in his heart, to be touched by it and truly want peace? Or does he now feel bullied, and will his anger begin to grow again? At what point do we stop seeking revenge? Is fear a positive? Or does it cause anger and vengefulness?

The story can bring about discussion of such issues. Raising questions has been the traditional role of folk and fairy tales: to examine our lives, and to safely “rehearse” the possibilities. Even the youngest children will have thoughts on these questions. Anyone who has experienced unfairness will have ideas.

Also to be discussed: what is the role of art in the world? If music is the only thing that calms this bully, what might that mean? What of other art forms?

That will lead naturally to a long look at the illustration, the colours used, the expressive faces of both humans and animals, the bright flowers in the healing garden, the positioning of the magical elements throughout.

In the end, there’s a lovely warming sense of family, with the father delighted over his daughters’ success, and his own yearning to be home—a positive landing place.

On the opening page, Yee dedicates the story “To a world without war.”

Here’s to a book that holds that hope!

*

Alison Acheson is the author of almost a dozen books for all ages, with the most recent being a memoir of caregiving: Dance Me to the End: Ten Months and Ten Days with ALS (TouchWood, 2019). She writes a newsletter on Substack, The Unschool for Writers, and lives on the East Side of Vancouver. [Editor’s note: Alison Acheson has also reviewed books by Leslie Gentile, Caroline Lavoie, Janice Lynn Mather, Li Charmaine Anne, Linda Demeulemeester, Hanako Masutani, Julie Lawson, George M. Johnson, Janice Lynn Mather, Jacqueline Firkins, Barbara Nickel, and Caroline Adderson for BCR; and Dance Me to the End was reviewed by Lee Reid.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster