Architectural legacies in ‘complex territories’

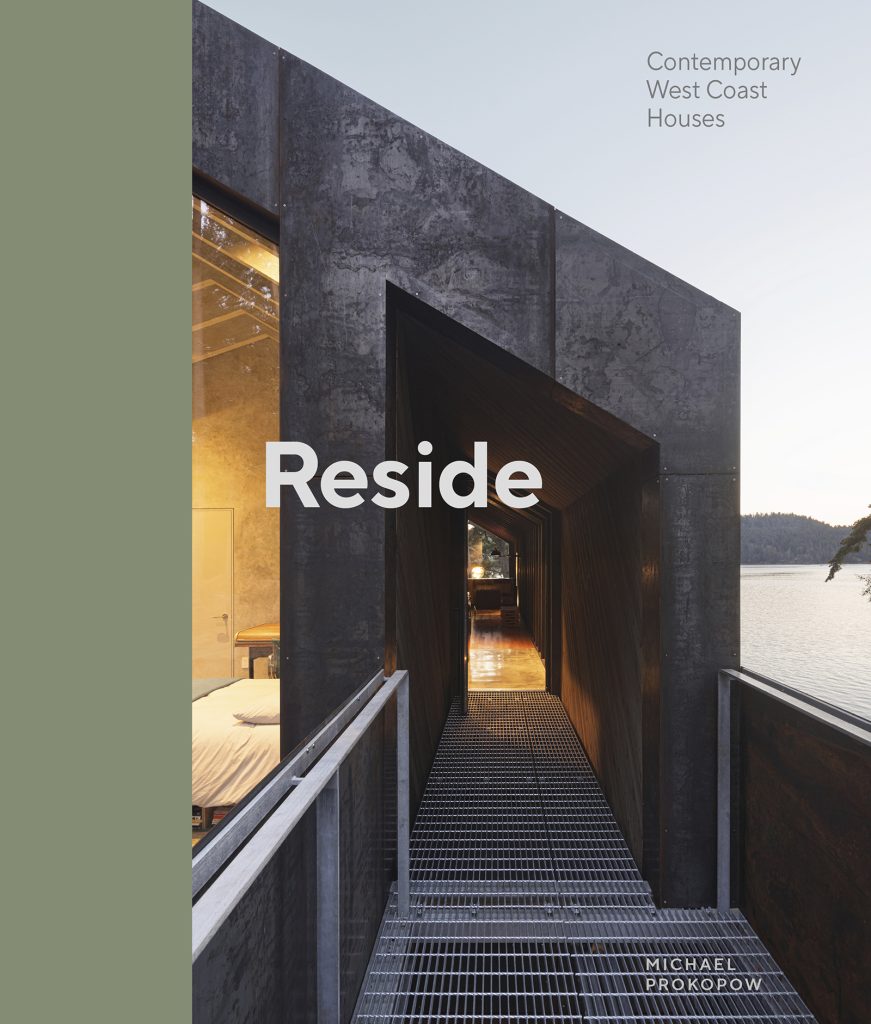

Reside: Contemporary West Coast Houses

by Michael Prokopow

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2024

$55 / 9781773272634

Reviewed by Martin Segger

*

Lavishly illustrated and produced, Reside surveys “the next generation” of West Coast architectural Modernism in British Columbia. Indeed, that is the title of the introductory essay by Clinton Cuddington.

Thirty-four short essays accompanied by colour photographs make up the bulk of the book. They are grouped thematically by location: Mountain, Forest, Shore, and City. The front flyleaf shows a map of the Province, with inserts, that mark the locations of the houses. Most are situated on Southern Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands, and Metro Vancouver. Although there is a brief end section with chapter notes and sources, the volume lacks an index, which is a pity.

Cuddington, an architect whose experience includes the office of Bing Thom and whose firm Measured Architecture contributes a project to the book, explains that Reside is an update or sequel to Greg Bellerby’s ground-breaking 2015 work, The West Coast Modern House: Vancouver Residential Architecture. Cuddington’s role was to assemble a group of representative practitioners to demonstrate the vibrancy and currency of the West Coast Modern, a continuation of the design tradition introduced in the 1950s by practitioners such as B. C. Binning, Arthur Erickson, Ned Pratt, Bing Thom, John Di Castri, Barry Downs, and others. Michael Prokopow, former curator of the Design Exchange, is a cultural historian with a distinguished academic career investigating the varied international streams influencing Western Canadian architects and designers. He skillfully knits the book together providing a preface, and an end-piece “The ‘BC Idiom’ Revisited: The Contemporary House in the Millennial Age”.

The essays or case studies each summarize essential details such as date, designers (including interior and landscape), contractors, engineers, and photographers. Street addresses are not provided, perhaps out of respect for personal privacy. The portfolio of photographs, up to six per project, is occasionally supplemented with design drawings such as plans or axonometric drawings. Each illustration is carefully labelled according to the angle of view or design feature represented. Prokopow’s accompanying text describes the design intent of the commission, technical features, a brief description of what amounts to walk through of the house, and concludes with a summary observation as to how the overall design fits within the aesthetic of West Coast Modernism.

The variety of designs addressed in the short essays is extensive. “Treetop House” by Evoke International Design Architects opens the Mountain section and is a good example of the timelessness of West Coast Modernism, as mid-century as it is contemporary and pure in its references to the Miesian geometric roots of the style. “Saanich Farmhouse” by Scott & Scott Architects addresses its rural setting, a skillful contextual design that brings together Nordic and Arts-and-Crafts influences for a sympathetic fit with location. Equally contextual but addressing a very different location (late 19th Century urban subdivision), “Union” by MA +HG Architects, demonstrates a creative response to the vertical built-forms of the immediate neighbourhood. This new “insertion’ politely steps back on the lot, an example of how to handle the current pressures for urban densification with contemporary sensitivity. A bit of surprise awaits the reader with “Francis Wood” which is actually a renovation of Victoria’s first heritage-designated modern house by the highly innovative pioneer mid-century modernist architect John Di Castri. The result is a sensitive recasting of Di Castri’s original cliff-hanging commission, adding – as Prokopkow suggests – another layer to the building’s iconic design heritage.

The final section contains entries describing the thirty-four architectural firms whose contributions form the book’s substance. Each is accompanied by a page of photographs covering other commissions representative of their work. Perhaps the most unusual inclusion here is Petchet Studio’s spirit houses in the “Little Spirits Garden” for the Royal Oak Burial Park in Saanich, Vancouver Island.

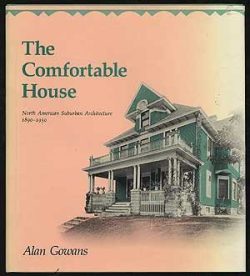

Michael Prokopow and I (full disclosure) share a common mentor: the pioneer Canadian architectural historian Alan Gowans, who founded and, for many years, chaired the Department of History in Art at the University of Victoria. Gowans is listed as one of four persons to whom the book is dedicated.

It is probably due to the influence of Gowans that we, as is common among his many students, share a deep interest in the function of architecture. By that Gowans would have meant a building’s role in society both narrowly in terms of the immediate clients but also beyond that as to its meaning in the culture of the times. Prokopow introduces the challenges of making such meaning, first in terms of current concerns around settler culture, built and otherwise, crowding out the Indigenous landscape amid current reconciliation agendas. He is particularly sensitive to the fact that no self-declared Indigenous architects, or clients, are represented in these pages.

The author continues to struggle with this issue in his final concluding essay, part of which he subtitles “complex territories.” The “BC Idiom” emerged from the intersection of a many ideas about building. Japanese, Chinese, Nordic, and American aesthetic traditions combined with the climate, geography, and native materials of locale or place. Embedded in this special place by way of history, tradition, and ecology was the presence of First Nations. Alas, they are absent from the standard narrative of Modernism. But as he points out, many minority voices were absent from the local culture of mid-century architectural practice. As a phenomenon, Modernism was, and still is, a minor slice of the domestic building stock. The style emerged among a small, elite, intellectual segment of society clustered mainly in Vancouver and Victoria that was predominantly white, male, wealthy, and completely “settler.” Open fluid interiors responded to a new casual lifestyle of the postwar family. Abstract sculptural forms devoid of overt historical references were favoured in contemporary art scene dominated by European émigré artists. This seems to persevere within the continuance of the design tradition through the years 2004-2023, as represented in this book. Whether or not this worries the author, he does not say.

Prokopow’s final note, a bit self-consciously, dwells on the usefulness of this book. It is not an academic study; nor is it a critical engagement with its subject matter. The essays are descriptive, informative, and illuminating. Many overriding issues such as whether or not any of this points to an eventual architecture of reconciliation, are not resolved. The texts of the case studies work well with the illustrations, which the author recommends readers “prioritize.” He admits there is an element of (healthy?) voyeurism in being able to walk through these houses, passing glimpses of other people’s lives.

I noted my daughter had bought the book as a décor piece, ostentatiously displaying it on the coffee table in her newly modernized living room. I asked if she had read it. “Not yet” she said. I have encouraged her to do so.

*

Martin Segger is an architectural historian, writer, and urban critic. He has written extensively on Victoria’s built environment. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of BC, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on BC historic and decorative arts. He is group-coordinator of the UNESCO Victoria World Heritage Project. [Editor’s note: Martin Segger has recently reviewed books by Raymond Biesinger & Alex Bozikovic, Allen Specht, Liz Bryan, Michael Kluckner, Marc Treib, and Daina Augaitis, Allan Collier & Stephanie Rebick. He has recently reviewed two previous exhibitions at the Wentworth Villa Architectural Heritage Museum: From the Ground, into the Light: Organic Architecture of the Islands, 1950-2000 and John Di Castri, Architect, A Retrospective (1924-2005) for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster