A Sound Education

by E.R. Brown

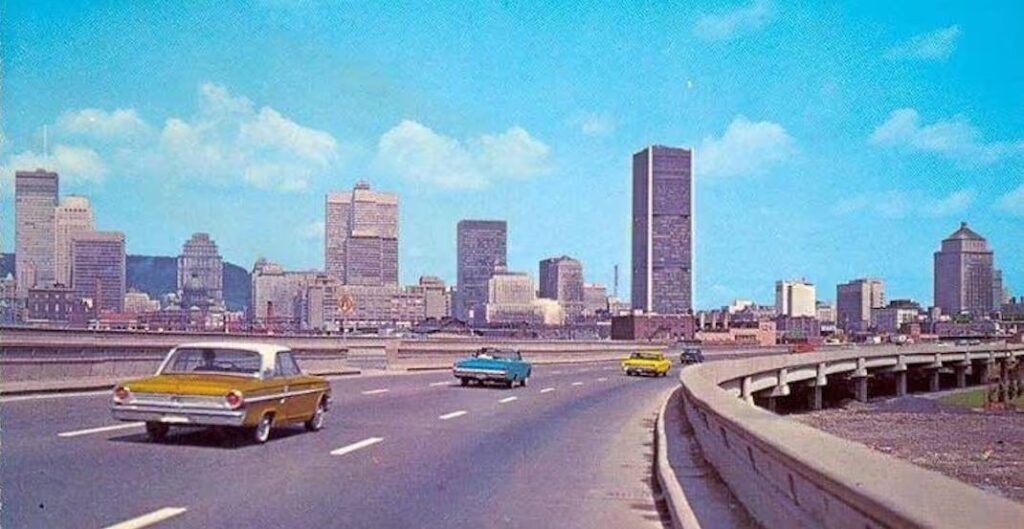

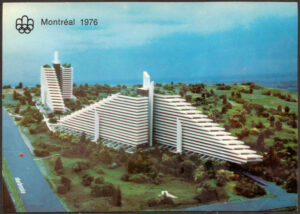

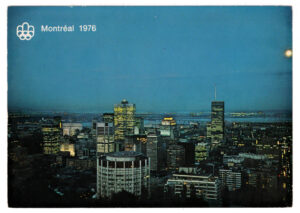

Montreal, 1976

A LONG NAKED LEG SLICES the air above my head, sending the bare-bulb worklight swinging. Reflexively I duck, even though I’m used to it by now, and I keep my hands locked on the sound gear, ready for the next cue.

“Hey babe,” she purrs, “Whatcha doing after the show?”

I shake my head. She is persistent. It’s a running gag, how that mock Lauren Bacall tone lands with her Aussie accent and the fact that she’s wearing nothing but a sequinned G-string and peacock-feather wings.

Her name is Roxy. She’s an acro-dancer at the Café Montmartre, an exclusive, expensive supper club in one of Montreal’s finest hotels. She’s waiting at the stage-right curtains for her entrance in the grand finale. I run the sound system, which is my six-nights-a week job. Daytimes I’m at university.

I’m stripped to my undershirt because it’s a steaming 35 degrees in the control booth, a grimy cubbyhole crammed with sound and lighting gear. She’s near naked because that’s the show: they start in CanCan regalia, ruffling their petticoats in rich patrons’ faces, and gradually shedding items as the show goes on. For anyone under fifty, it’s weirdly unerotic.

Roxy struts her winged apparatus with supreme confidence. Stage makeup exaggerates her eyes, which are large, dark, and soulful. Then there’s the lipstick she applies to her nipples. When she caught me staring as she touched it up, her hey babe was how we started chatting.

She’s still waiting for my answer. “Are you all going somewhere? Isaac?” Trying to include the lighting op into the conversation.

We have a connection, Roxy and I, but we won’t be going anywhere, not as a couple. First, we’d send the Cafe M gossip circle into overdrive. Second, I have a girlfriend.

Third, which Roxy doesn’t know about, it’s end of term. I’m a joint major in music and communications. Before morning I have to proofread a paper on micropolyphony in Ligeti’s Atmospheres, and at nine I’m booked into the Electronic Music Studio to edit my music track for a student film, a violent little feminist sci-fi short called Marge.

Isaac doesn’t bother to answer. His sweaty armpit is inches above my shoulder and his eyes—and mine, too—are on the singer onstage, Giselle (“Direct from the Lido in Paris!”) as she drags out the last notes of her signature song. Isaac claims it was a hit fifteen years ago in Belgium. Her backup music is on tape—the tape deck is rolling right beside my forearm—and if she milks it too long, the tape will run out and she’ll be singing over silence. That would be my fault, of course, and she’ll dump all over me when she flounces offstage.

Giselle’s not my concern. I’m locked into the next cue, which will be in blackout.

Giselle’s final note tails off and Isaac plunges the faders. In darkness I trigger “Life in the Fast Lane” and bump the volume to 10 while Roxy and the dancers glam onstage for the slam-bang finale.

Isaac and I are tight, like I imagine firefighters are, or soldiers in the trenches. We spend nearly every night in this five-by-eight cubicle, jammed between tape decks and a wall of steel levers—long mechanical faders that Isaac raises or lowers to control the lights. It looks more like a WWII submarine than a modern theatre. When he runs out of hands, he uses a knee. When Isaac clambers my way, I have to contort myself to let the fader swing past one ear, never losing my grip on the controls or my view of the stage and possibly missing a sound cue.

Isaac has warned me about Roxy.

The dancers tell me that there are similar clubs in Paris, with the same Parisian Playboy air of seedy sophistication. I’m not sure, but the job is a blast. For ninety minutes, two shows every weeknight and three on Saturday, I have nothing to think about except moving microphones, setting sound levels and keeping the twin Revox tape decks in sync, and never, ever, missing a cue. There are hundreds of cues, from sound effects like car horns, breaking glass, the pop of a champagne bottle (timed to a comedian’s act) to musical numbers, all in sequence, with no possibility of rewinding if something is missed.

It’s pure adrenaline, and as far from fine art as I can imagine, but when the show’s running I have no school deadlines, no rent to pay, and no Jane at home, already asleep by ten.

The things people do for a living has been an eye-opener for a kid from the burbs. My dad runs a corner store. Here, I’m working with past-their-prime nightclub singers and specialty acts that the Gellért organization pulls from around the world. I’ve put together effects and music for a ventriloquist/magician (“Direct from Las Vegas!”) and a Spanish clown. Currently, it’s The Amazing Aguanidos, a pair of massively muscled acrobat twins.

I like Aguanito and Aguanando. They speak some Italian dialect, Calabrian or Sicilian or something, but they are effusively friendly, shaking my hand every evening before they go on. Nobody in this town has seen anything like their act. They open with leaps and tumbling. They juggle in sync with the tape. Standard Ed Sullivan Show stuff. Then Aguanito braces himself at one side of the stage, arms raised, while the music slows to a drumroll. His twin bounds onto a springboard and flies above the curtains, reappearing head-down like a diver, and landing in a handstand in Aguanito’s upstretched grip.

Every night, right on cue, the audience goes nuts. There’s no stage trickery here. The diners are so close they can see the cabled muscles in Aguanito’s neck and the sweat coursing down his balding forehead.

But it’s not over. Aguanando, the upside-down twin, lowers his head onto Aguanito’s, and they release their hands. Balanced head on head, they dance a jig, followed by upside-down, rightside-up juggling. While the audience is enraptured, stagehands lower a trapeze from the ceiling, and in a clever bit of balance work, the head-conjoined twins end up swinging, only a few feet above the shocked (and suddenly silent) audience. Aguanando’s head is on the steel bar while Aguanito is suspended below. There are no nets or safety straps. Their steely grip on each other’s forearms is all that keeps them from crashing onto someone’s filet mignon.

I wonder how many of those with their necks craned up notice the frayed seams on Aguanito’s jumpsuit, or the white roots under Aguanando’s dyed hair. Every night I hope that neither of these sweet, aging guys injures himself, and wonder what they’ll do when something happens.

After the show, it’s a twenty-minute walk uphill from the hotel to the 24-hour Indian restaurant, over Montreal-in-March sidewalks rimmed with black-edged, oily remnants of the winter’s snowpack, pockmarked with crusty white dog turds. It’s near midnight, the streets are quiet and Roxy and I haven’t spoken much. The others have gone on ahead.

Finally, she says, “How’s Jane?” Roxy’s skin is chafed and raw, probably more from the stage makeup than the cold. Her fingernails are bitten ragged. She’s gorgeous.

“Doing great.” Which is not true. We haven’t spoken in days, maybe a week. Every time we do the gulf widens. “Once she’s done her final exams, that’s it. An official Bachelor of Science.”

I feel a stab of guilt that she remembers Jane’s name. What do I know about Roxy? That she’s from somewhere outside of Sydney. Tallawong? Wallongong?—wherever. It’s the home of Tibor Gellért Acro-Circus-Dance School, where she and the other dancers started as kids, from where they were hand-selected for a life of travel and glamour.

I might think it’s a racket, that organization, but I keep that to myself. Roxy’s made it to soloist. She’s performing halfway across the world from where she started. Who am I to criticize? Even it means getting by in near-poverty.

I can feel her next question coming and want to get off the topic of Jane. “She got a job already. Apparently genetics is hot.”

Roxy raises her eyebrows in that way some people do when faced with science smarts. As though it’s a whole incomprehensible universe. I know the feeling.

“Squibb Pharmaceuticals, starting in April. A nine-to-five job.” I shrug.

I don’t get it either, why you’d want to work in a cubicle somewhere, mired in routine? But that’s what she’s always wanted. We were teens together, Jane and I. She played drums and sang. I played bass. We discovered films and books; we’d lay on the golf course at midnight smoking weed, laughing and talking about life, about who we thought we might be—later, when we were older.

Now she’s gung-ho to get started, to make steady money and move on up, wherever that might mean. I’m glad for her, although I wish she’d make some effort to close the widening gap between us. I don’t make much but I’m paying all our bills, which I hope has helped her earn the Honours and Distinction on her BSc.

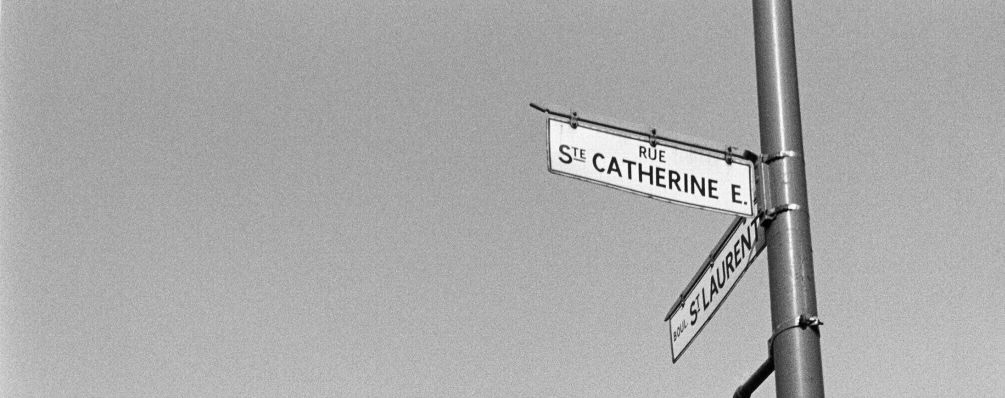

Working six nights a week hasn’t helped my grades, except for the composition courses. I’ve had a couple pieces performed, and not just student performances. Still, I’m aware there’s no money in contemporary music. That’s why I trained as a recording engineer. But it’s the way Jane tosses out that word music, though—as if it’s distasteful and certainly unserious. Which I realize, as I extend a helpful arm to Roxy as she stretches those long legs over a lake of slush at Ste-Catherine at Drummond, is why I’m in the studio or at Café M at just about every hour she’s awake.

A wistful thought flicks past: when did I last see Jane’s nipples?

Opening the door of the Indian restaurant, I raise my voice over the late night crowd. “They’re going to be talking about the new show. Who’s staying, who’s moving on.” The dancers got the news in their afternoon rehearsal, but I work nights, so I’m out of the loop. I give her a what-about-you look.

“I wouldn’t leave.” She waves a fingertip at the Cafe M crew in the back. “Not without telling you first, babe.” Her joking-not-joking gaze locks on mine for a nanosecond then flits away.

I check my watch. Nine o’clock in the studio is not far away. The Ligeti paper will be submitted as is. Fingers crossed.

We squeeze in beside Isaac, making six of us at a Formica table made for four, sharing two servings of yellow duck curry and naan bread. The restaurant is humid, and the windows facing Ste. Catherine stream with condensation.

There’s Lenore, a soloist like Roxy, and Colin, one of the two male dancers, and Bridget, the ballet mistress, who lives with Guillaume, the stage manager.

They’ve just toasted the news—to me, anyway—that Bridget and Guillaume got married over the weekend. He’s been promoted to Gellért’s Monaco office and French citizenship will open options for her outside the organization.

“At the end of the season?” I ask. Guillaume nods. “That’s in, like, two weeks.”

Throughout the company there’s an undercurrent of restriction, of confinement. Apart from the stage crew, everyone comes from overseas, with work visas that bind them to Gellért. If they quit they have to leave the country. They’re only paid when the season ends. Leave early and their salary is forfeit. It doesn’t sound legal to me, but nobody questions it.

I look to Colin for a reaction (he has a Canadian girlfriend and there’s already talk) but he’s in the corner quietly taking more than his share of curry. I turn to Lenore. “And you?”

“I thought I was going to Barbados.” She makes a face. “I’ll miss the Aguanidos. They’re so cute.”

Isaac laughs. “What are you going to miss? The sign language?”

The twins are headed to Lake Tahoe along with Giselle (“Direct from the Lido!”) I’m glad they managed one more contract.

Lenore taps Roxy’s forearm. “No worries, babe. We’ll be together. Rehearsals start on Monday.”

Roxy purses her lips, and I know there’s more she’d say if I weren’t there. She loves her job but I have Canadian citizenship.

These days it feels like I understand Roxy better than Jane. Roxy’s homesick but doesn’t want to go home. She’s lonely even though she bunks with three other dancers. She’s shy and insecure, even though her onstage persona is commanding.

Isaac elbows me. “Ready for another changeover?”

I nod. “School will be out by then. I’ve got the time and I need the money.”

We both know what’s coming. Café M will be black for a week, and in that time the old sets come down, new sets go up, new lighting and sound designs are whipped together—including the the cue-to-cue showtape—in time for final rehearsals before the curtain rises on opening night.

The last changeover took place during Christmas week. It was a good thing, Isaac and I joked over a warm-beer breakfast on Boxing Day morning, that he wasn’t Christian and I was barely talking to my parents.

“Mr G wants a private lunch,” he says. “With you.”

“He told you to tell me?” Isaac nods. Tibor Gellért barely knows that I exist. “You were talking to him?”

Suddenly the realization strikes. “Guillaume is leaving. He needs a stage manager.”

“He doesn’t need a stage manager, he has a stage manager. You’re looking at him.”

“Well done.” I raise my half-empty glass. “Life in the booth will never be the same.”

Isaac deserves it. I don’t think he has high school, but he’s smart as hell, and he never loses his cool no matter what goes wrong. He’s been the real stage manager all winter (Guillaume is pretty useless). And he’s paid his dues for Gellért, sweating in that control booth for years.

What Isaac doesn’t know—what no one here knows—is I won’t be in the booth either.

A couple of weeks later, I spot Mr G across the hotel lobby. We’ve already met—a handshake, nothing more—during the Christmas changeover. He’s stooped and rail-thin; his blue velvet jacket drapes over his shoulders like he’s a coat hanger. He’s either a millionaire or someone who dresses like one, with silk shirts and handmade shoes and heavy, gold-toned eyeglasses that magnify his eager welcome. He grasps my forearm and we walk to the booth he’s reserved.

“Call me Tibor.” His Hungarian accent is heavy. He’s made a point of seeking me out, he says, he’s so impressed with my work. He grills me on brand names of microphones, amplifiers, and speakers, asks about performance and reliability. His teeth are so white and even they look as though he just popped them in, but they don’t hide his weathered look. I don’t need to see the numbers tattooed on his forearm, Isaac has told me they’re there and what they mean.

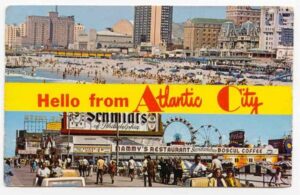

He leans closer, like he’s bringing me in on a conspiracy, and I respond by leaning in too. He has a show coming up, he explains, a big show, in Atlantic City, with Jose Carreras, maybe Placido Domingo. The sound will make it or break it. His magnified eyes narrow. “Look, son, this company is going places. The opportunities are enormous for an ambitious and talented young man. A man like you. I need people, the best people, but only if they are with me. Are you with me?”

For a moment I am with him. For a moment, it feels like the Gellért organization could be my future, the way it is for Isaac and Guillaume. But only for a moment. What does he really want with me? I’m still in school. I turned twenty-one a week ago. I just broke my girlfriend’s heart and I’m crashing on a friend’s couch.

And I have a new job.

I do the changeover and I leave Gellért. I find a replacement, a music student who knows sound equipment, and I train her on the cue-to-cue and hope for the best. Isaac stops talking to me. Roxy’s still my friend, but that won’t last. I like her more than I can say, but it’s not the time for a new relationship, and we both understand, I hope, that the citizenship thing would only entangle and complicate things. I’ll miss her. And I’ll miss this weirdly mob-like cult of an organization that, at a minimum, exploits young and has-been performers. Leaving is the right thing to do, because I feel complicit somehow, but I know I’ll miss it.

What I don’t know is that I’m about to find myself working, indirectly but seriously, for the real mob.

* * *

“NOW THIS,” Paul Beaugrand raises his reedy voice over the pounding jackhammer in the hallway. “This is the real thing.” He has a slight slur to his accented English, probably from the four beers he called lunch.

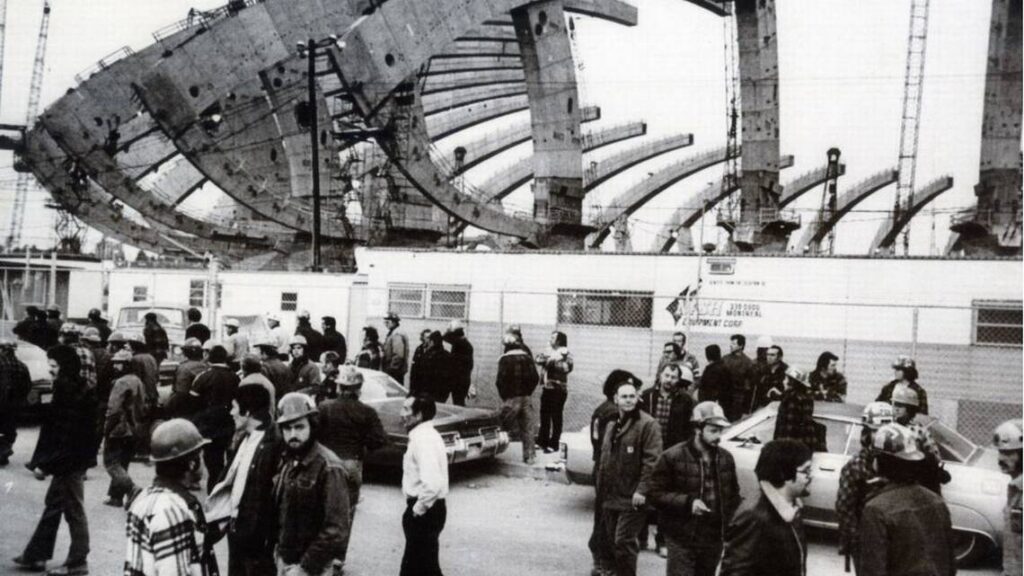

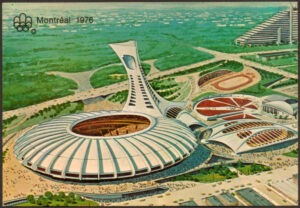

It’s a hot dry afternoon in May, and even in the shade I can feel concrete dust sticking to my back. We’re in what will be Canada’s largest sports stadium, the main venue for the Summer Olympics. The Big O, it’s called. Or the Big Owe, because costs are four times the $250 million estimate and still climbing.

Tall and bony, with Beatle-length black hair and a thin beard, blue-grey skin with burst vessels across the cheekbones and veined eyes to match, Paul is standing where the sound console will go. We are the sound team, Paul and me. He’s the senior, and there are no spares. The opening ceremonies are seven weeks away.

“Pretty damn classy,” he says, nodding approvingly at the unfinished concrete, the gaping holes where windows and doors will be, the snaking bundles of audio cables erupting from the floor and dangling from the ceiling. With that lopsided grin I never know when he’s kidding.

When it’s ready, if it’s ready, it’ll be slicker than Star Trek, with the best equipment money can buy. For two weeks, the pair of us will work with announcers—their booths are unfinished cubicles below us—and pull sound from the stadium floor to catch the sounds of athletes pounding over the track or crashing to the ground. Or accepting a gold medal. We’ll feed that sound to the spectators, up to 70,000 of them, and to the world’s largest broadcasters.

Everything will be live. Looking out on the unfinished stadium I feel sick.

Workers swarm around us, hanging cables in the ceiling, slapping up wallboard, screwing in lighting fixtures, siliconing ceiling-to-floor windows. Paul Beaugrand is the real thing. A career sound man, he’s worked in just about every major theatre and club in the city. He’s toured the continent with René Simard and Diane Dufresne. I think he’s in his late thirties, but his seamed face looks ten years older.

What am I doing here? I worked one season in a seedy little supper club, where a fuckup would be heard by a few hundred people, max. This is the Olympics. Millions of people will be listening intently.

Paul gives me that grin again. “Tout est sous contrôle?” Which is his line these days—everything’s under control?—usually meaning the opposite. Maybe he senses my panic. Then he blanches and wobbles—I’ve never seen anyone wobble before—and heads directly toward the washroom behind us. The sound crew’s private washroom, which still has no doorway, and, Paul soon realizes, no plumbing. A hand to his mouth, he elbows past a worker carrying an armload of lighting fixtures and staggers out to the hallway, where the public toilets work fine.

Does the sound crew really need that level of privacy?

Yes, they say. We need a secure bunker. Because the ‘72 Olympics are mostly remembered for the Munich Massacre, where terrorists killed eleven Israeli athletes. For ’76, the experts say the sound system is a prime terrorist target: the wrong announcement could stampede spectators and result in mass fatalities.

And we’ve apparently passed thorough background checks. We both have 001-class ID tags, the highest security clearance. An 001 tag gets you anywhere, from the press rooms to backstage at the opening ceremonies to the Queen’s royal booth.

Which I reflect on as Paul returns, wiping damp stains from his torn Beau Dommage t-shirt. The silicone fumes, he says, he’s sensitive. I’m not going to comment, but his Labatt lunch can’t have helped.

We leave the future control room and descend to ground level, checking my COJO binder (COJO is the Olympics organizing committee; ultimately we all work for COJO) that shows the cable runs from the control room to the stadium floor. It’s hard to envision the miles of microphone lines that are buried beneath the rutted bog of dirt and tire tracks.

Paul pauses. There’s that grin again. “Câlice, s’gonna be big.” He extends one arm to the north end of the field, where a flattened stub represents the future tower and retractable roof. One day they’ll finish the tower, they promise.

“Biggest opening ceremonies ever. Biggest sound system in the fuckin’ world.” He makes a fist and chucks me, gently, on the shoulder. “And we get to build it.”

Technically we don’t work for COJO. We work for a subcontractor, a small audio company run by a manager named Claude. The company has a storage depot and workshop east of Papineau, in an old brick warehouse that’s lined with racks of speakers, bins of cables, mixers in wheeled shipping crates. It’s like a wrecking yard for sound gear, complete with chainlink fences and guard dogs.

It’s a June afternoon, hot and muggy after sudden cloudburst, and the Olympics crew sit at folding tables out by the loading dock, with the doors rolled up to let in the sudden sunshine. Armed with screwdrivers and soldering irons, we’re stooped over microphone cables and power amplifiers, breathing a blend of cigarette smoke, solder fumes, and steaming asphalt as we assemble the World’s Biggest Sound System.

(Which is, apparently, true. Once it’s been used for the Opening and Closing ceremonies, this enormous 64-speaker array, which takes two semi-trailers to transport, will leave on the Emerson Lake & Palmer World Tour. We’re building a system for ELP! For a World Tour! Even the old guys are in audio-geek heaven.)

It’s a mellow atmosphere. There’s a beer fridge. People come and go. All the crew, except me, has worked together at one gig or another. They’re on leave from their real jobs in nightclubs and recording studios or rock bands, and it’s like summer camp for old sound guys (and they are old—not one’s under thirty; some are in their forties). For me this is a summer job. I’m twenty-one, the only Anglo here, and the only one who’s going back to school in the fall. Probably the only one who’s been past high school.

Everybody seems cool, even though my French is as accented as Paul’s English. While we solder away, cars and vans roll into the loading dock and people stroll in and drop off or pick up whatever they’ve rented and shoot the shit. We have a daily quota, and once we reach our number we can leave. Or stick around and earn bonus pay. I’m starting early and staying late—I’ve got nothing at home except a couch to sleep on—and my paycheque is doing well.

I like soldering. Before this job began, I put together a hi-fi outfit for a couple of rich guys. They live in an old church in the Ottawa Valley. The big room’s an art gallery where they hold informal concerts. I’ve played there, live electronics, and they asked me to help them improve the sound. So, Claude put me on the hi-fidelity table. I’m doing electronic surgery on power amplifiers: snip this, bridge that, put it back together and you’ve doubled its output power. This system is going to be a monster.

I’m enjoying a job that doesn’t have a countdown until the curtain goes up. Where you can take the time to get it right.

I pause to straighten my back. Beside me, Paul’s taking a pull of his beer.

“You know what’s weird?” I say in French (Tu sais c’qui est bizarre?), “On our timesheets, this is logged as security training.”

That lopsided grin again. “It’s a flexible schedule.”

“We’ve been here two weeks now.”

“If you want the job, you do what they say.” His shoulders lift in another shrug. “This is a good place to be. Everybody in the business comes in here.” He picks up his soldering iron. “So why’d you cut your hair?”

I run a hand over my fresh new inch-long fluff and across my shaved cheeks. “I’ve changed a few things in my life.” I’m single again, and hoping to find a place of my own. My photo ID looks like a different person.”

One of the guys listening in says, “Take six inches only, why not? Don’t need to go that far.” Heads around the table nod. Long-haired, mostly bearded heads.

There’s a moment of disapproving silence. It’s like I’ve broken a code. Truth is, it feels like long hair’s redneck now, not hippie, and these days I’m feeling closer to David Byrne than Lynyrd Skynyrd.

A delivery truck backs in and off-loads a dozen crates. They’re speakers. JBLs. With the COJO logo on the delivery stickers.

“For the control rooms?” I ask Paul.

“Good shit.” He’s right. They cost more than a used Toyota.

A half hour later a Pontiac station arrives. The passenger is a lanky guy with a shoulder-length braid. I recognize the face. I’ve worked in his studio, but never met the man himself. He waves and half the table rises from their stools, calling “J-C!”Jean-Claude Plamondon shakes everyone’s hand, even mine, and grabs a beer and catches everyone up on his Studio Champ-de-Mars. Bowie was just there with Carlos Alomar, he says, hinting that they’ll be back.

Paul elbows me and points to J-C’s driver, who’s leaning against the hood of the Pontiac. “Help the man. He’s here for a pair of those.”

“Really?”

“He recorded the opening ceremonies music. When the athletes come in.”

Are the monitors payment? I don’t have to ask. Then, another thought. “But there’s a live orchestra. That’s why we’re building this.”

“It might rain.” His grin is wide. “Hey. Everybody dips their nose in the trough.”

I’d love to work for Jean-Claude Plamondon. I go and help.

For the rest of the day—and the following weeks—cars and trucks come and go, loading speakers, cables, stands, and all kinds of gear with a nod and a handshake, most with COJO labels.

Don’t worry, Paul says, it’s nothing serious. It’s kind of funny, if you see it that way. Ripping off the man. I must look like an uptight Anglo.

He raises an eyebrow and says in a flat, cut-the-crap tone, “You want to work in this business? This is the business. It don’t matter if you make a drum kit sing, you gotta help the bosses make money. You think some Swiss bureaucrat in COJO cares about this shit? No. But ordinary people do.” He extended his arms to encompass the entire East End. “We gotta spread it around.”

From July 17 on, the Games consume my every minute. I’m the junior partner, so I’m first on site. I know our Army guards by now. It’s always the same pair in camo outfits and full weaponry outside the control room, silent and uncomplaining.

As I’m running the morning calibration routine, our military musician arrives. Handcuffed to his wrist, like something out of a spy novel, he carries a locked briefcase containing the sheet music for every national anthem. All day, every day, he sits silently beside our tape library of national anthems. Before a gold medal is awarded, he compares the tape of the winning country’s anthem to the sheet music. That’s his entire job for the duration of the games.

Next to arrive is the vocal talent, a rotating array of French and English speakers. They come bundled in neck scarves even though it’s July (to protect my instrument, you understand), and pull out spray bottles to spritz the air around them (it’s so dry in here) and suck herbal lozenges before their daily warmups of growls, hums and whale noises.

Next door to us, through a glass wall, the Swiss Timing team TV sets up their screens and computer terminals, studiously avoiding any glances in our direction. Paul’s gone out of his way to make fun of their suits and ties and prim Swiss French.

Paul arrives last, with a booming Tout est sous contrôle! that must rattle their Swiss tie-pins, and pulls a half-dozen quart bottles of Labatt’s 50 from a crumpled paper bag. Breakfast and lunch. (Although, after a few days I bring extra bagels and sandwiches, and Paul doesn’t complain.)

Every day, it seems, some official or other will crashing in here with a complaint—we haven’t announced some result or other (we don’t decide what gets announced; there’s a protocol), the announcers are too quiet or too loud (the levels are preset; we can’t change them) or there’s a special request. Yesterday it was an IOC member’s birthday, and some Belgian dweeb wanted us to play Happy Birthday (we don’t have that tape, and besides, no.)

Whatever happens, Paul likes his Tout est sous contrôle. Partly because it’s not always true: equipment is crapping out and we’re faking it and it feels like I’m running ten miles a day down to the field and back to swap out mics or cables. But so far we’ve made it work. The tens of thousands of spectators, and the millions of television viewers, haven’t missed a single update.

Seven days a week, fifteen hours a day is my kind of work schedule. I don’t want to think about failed relationships or old friends who’ve decided to shun me, I just want to work.

It’s the final day of competition.

Canada’s national anthem has not been played once. They’re saying that it’s never happened before, not a single gold for the host country. Today won’t break the record. We’re not a contender in Show Jumping.

Equestrian sports were held in the country, out in Bromont. A few days ago the fields there turned to mush in a massive rainstorm, and someone decided to bring the Show Jumping finals here.

It’s a sudden panic. The track and field surface has been cleared away and organizers are setting up the judges’ tables. The horses will run—and jump—around a timed circuit, triggered by the ding of a judge’s bell. My job, according to the COJO binder, is to point a microphone at that bell. I leave a note for Paul that I’m headed to the field with a shotgun microphone and stand and a comms headset.

Why this field is better than Bromont’s I can only guess. We had the same rain. The turf is like Waterloo after the battle, a spongy wet mess of thrashed bluegrass where chalk lines have been laid and removed, divots torn up and replaced over two weeks of intense competition. Buried out here, deep enough to be safe from cleated shoes, launched javelins and thrown hammers, are a half-dozen underground boxes containing microphone plugs and headset outlets. We learned how to pop them open during the dry runs in June.

But those were dry runs.

I find the telltale pull tab and haul on it. The sodden grass resists, then rips upward, lifted by a grey plastic lid that heaves open, splashing globs of dirt into what lies beneath.

The box is a flooded mess. The mic outlets are under six inches of water.

When the planners decided not to complete the roof over this stadium, did they tell the sound installers to use waterproof, outdoor-grade equipment?

I stand up and scan the field. Any underground outlet will be the same. The above-ground plugs are on the far side of the jumping circuit. A cable from there would risk tripping a horse.

I have no idea what do. Show Jumping starts in ninety minutes.

Eighty minutes of panic follows, in which Paul and I work though every plausible solution. We call the other venues. We call our boss Claude.

Every few minutes another panicked official knocks on our door, elevating in rank from the Canadian Equestrian Foundation to the North American to the European. Nobody’s saying Tout est sous contrôle.

We ask the guards to block visitors and give up. Paul cracks open a quart bottle of Labatt’s and offers me a swig.

The control room door opens.

Paul snaps, “Va—” which is going to be Va chier, except for my hand on his arm. Or perhaps he, too, recognizes the visitor, a beak-nosed geezer in a three-piece suit with tails and something ribboned and ceremonial on his chest. Paul might know him from the news. Two weeks ago, I stepped past him when I set up the microphone for his wife, Queen Elizabeth.

Prince Philip doesn’t bother to introduce himself, he launches into a tirade of insults and belittling profanity, accusing us, in the poshest of English accents, of unbelievable bloody incompetence. Paul turns pink and spins his chair to face the prince, but can’t get a word in. I lose track of the things that we’re called—cocksuckers and arseholes are some of commoner items—but we are damned to hell for destroying this event, this pinnacle of sport. “If that bell isn’t heard all the way to England,” he puffs, running out of wind, “the whole bloody thing might as well be called off.” He sags, turns and leaves.

At first I’m outraged. Then I’m kind of amused. I mean, Prince Philip! I knew he was a navy man, but holy crap. Then I just feel gutted. He’s right. I run through the things I should have done, the double-checks I should have made, the alternatives that we could have tried if we’d known. But it’s too late.

Or not: I spend the day in one of the announcer’s booths, with binoculars borrowed from Swiss Timing. The microphone is pointed at a water glass. Whenever I see the official’s finger twitch on the bell button, I tap a ballpoint pen to the glass making an authoritative clink. The technology is basic and I’m terrible at it, but the damn bell is heard all the way to England.

It’s mid-August. The Olympics team has been assembled for one last beer and pizza. It’s good to see Paul again.

My life is moving in the right direction: in September I’ll be in a studio apartment above a deli. It’s small and the smells rise up, but I won’t have to move back to my parents, who’d like nothing better than to gloat. My Olympics money won’t take me past December, but I’ll figure out that later.

The guys got together once after the Games ended: Emerson, Lake & Palmer visited, in person, to test the World’s Largest Sound System. They needed a hockey arena to fit the whole thing. When Greg Lake stood under the suspended array and struck a low E on his bass, enough air was pushed (by 128 woofers!) to send the tons of hanging speakers swinging backwards. Lake ran offstage in terror. But wow, it’s loud.

After lunch, Claude leads us to the loading dock waves an arm at a waiting van.

“Take a pair,” he says, “for a job well done.”

More JBL monitors. Worth thousands. It’s a payoff, I get it. For what we saw, all those COJO labels leaving the shop.

Paul shakes his head, insulted. “Why do they do this? Like I’m gonna say anything.” He punches my shoulder. “Or you. There’s no trust anymore. No respect.” He sighs and downs a mouthful of beer.

He’s right, in his way. All summer long Claude and his company have been casual, trusting us with the whole scene. Now they want us to know who’s boss. To be in their debt. It sucks.

“What if I don’t want them?” I don’t have anywhere to put them, for one thing. They’re waist-high.

He nearly spits out the beer. “Then don’t take ‘em. You think someone’s gonna break your legs? That’s not how it is. But you don’t take ‘em, don’t expect to get get hired again. By Plamondon, by anybody. That’s all.” Then the lopsided grin returns. “They’re fuckin’ good speakers.”

I’m going to school. I’m out of this business. Do I need these connections?

Still. Those JBLs are worth a year’s tuition, maybe more. And I know a couple of rich guys with a church where they’d sound great.

*

E.R. Brown is a fiction writer and editor. His novel, Almost Criminal, was a finalist for an Edgar award and an Arthur Ellis award, was named a Book of the Year by the 49th Shelf review site, and was translated into Japanese. His short stories have appeared in magazines ranging from Prairie Fire to Mystery Weekly, and dramatized by the CBC. He is a graduate student at Simon Fraser University. Originally from the Montreal area, he lives in Vancouver.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (nonfiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction and poetry)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “A Sound Education”

Characters are colourful and come to life. Interesting insight into behind-the-scenes activities at the Olympics. Well-written.