Diffident souls in liminal states

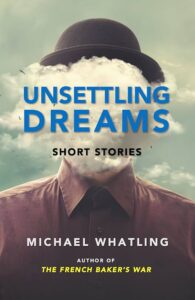

Unsettling Dreams: Short Stories

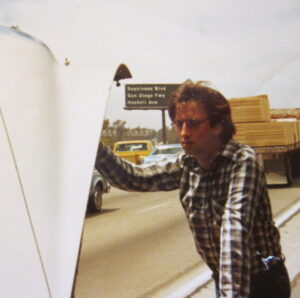

by Michael Whatling

Victoria: Mortal Coil Books, 2024

$16.99 / 1777569958

Reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

Michael Whatling, author of Unsettling Dreams, makes doubly sure to emphasize the imaginative link between his debut short story collection and Franz Kafka’s iconic short novel, Metamorphosis: the writer, resident of Victoria, chooses both a title and epigraph that refer directly to the ghastly experience of Gregor Samsa, Kafka’s protagonist. Readers braced for stories that read like “unsettling dreams,” however, may be surprised that, far from dreamlike, almost all of these short stories are almost painfully lucid. In fact, this is true of even of the three least straightforward narratives—one a futuristic dystopia, another filtered through the mind of a delusional young man, and yet another constructed as shards of street youth consciousness.

The stories may not read much like dreams, but are they “unsettling”? No word could be more appropriate. “The Empty Seat” is an acute example: an anxious and bullied office worker scuttles off his commuter bus to escape from a frighteningly unhinged fellow passenger. Building tension as his protagonist scurries through the dark streets, Whatling (The French Baker’s War) ends the story in a way that is all the more “unsettling” because it is not explicit. In dystopian “Americium’s New Flag,” the author likewise combines mounting tension and sinister vagueness: Elizabeth nervously rationalizes her anxieties about her husband’s safety in the face of escalating threats from an ominous big brother figure. She is delivered, finally, only a terrible euphemism. Unsettling? You betcha.

In most ways, in fact, it is what Kafka’s protagonist experiences after he awakens from his “unsettling dreams” that most links these thirteen stories. In fact, while there is an almost virtuoso variety in these stories, as a collection they are strikingly unified by a vision of those who, like Samsa, struggle with the pain and strangeness of being solitary.

Diffident, sensitive, and anxious, most of Whatling’s protagonists—boys and young men typically—also make their way alone. One says, cautiously, “He confessed he didn’t have many friends, and I said I didn’t have many, either. Or any, to be honest….”

The protagonist in “Holy Ghost” likewise reflects, “I’m almost eighteen, so it’s okay for me to be on my own, though I notice I bite my nails more than I used to.” In “The Freeman Tavern,” thirteen-year-old Rutherford, bullied and taunted both by his drunken father and by his pedophile bar buddy, is without a shred of support and, like so many others, utterly mute and passive. In “are ‘friends’ virtual?” a boy feels as if “he’s the last one left in a world devastated by nuclear holocaust.” Callaghan, the alienated protagonist in “The Empty Seat,” curses not just his “miserable existence, but mostly himself for being unable to do anything about it.” Echoing him, the lone protagonist in “The Spanish Lesson” sits paralyzed and tongue-tied, as he yearns to intervene between a beautiful girl and two drunken louts.

As if to reinforce the sense that his protagonists are strangers in strange lands, Whatling begins and ends with stories centred on the same boy. In “Indian Land,” the author documents an incident in 1974, when white residents on a reserve near Montreal were forced to move. Displaced, the protagonist, a boy, scrupulously avoids other boys in his new town. His bleak understatement highlights his profound separation: “I think it will take some time before I can find my way around.” In the concluding story, “Dog Cemetery,” he returns to the reserve to find a job digging graves for dogs. After an astoundingly intense, though isolated, experience, he feels himself further trapped in silence than ever—even in the presence of the old woman who has hired him: “We drive back in silence. I want to say something to the Old Lady, but I’m not sure she’ll understand. I’m not sure I do.”

What’s striking about the boy’s state of mind, though, is something much larger. What he would like to tell the old woman, but cannot, is that he has just had a visionary experience: “I’m at both ends of a microscope at the same time: I see and am seen.”

Although this is the most vivid such event Whatling writes about—and places as the end of his collection—it is characteristic of a second string of associated themes. Indeed, as much as this is a book of alienated, diffident souls, it is about liminal states too, states where realities pull apart. Quite apart from the duality of the boy’s vision is the duality of his identity: he is neither “Indian nor white.” Similarly, the young woman protagonist in “Through the Woods” finds herself almost beyond emotion or understanding, as her partner tells her their relationship is over. She is in a limbo between dualities, realizing that “the things she never had, but cherishes, are more valuable than what he has, but never knew.”

Many of Whatling’s other characters are similarly unmoored from opposing certainties. In “And They Still Play War,” Reeves finds himself trapped into re-enlisting in the Vietnam War in order to earn the money that will keep his younger brother in school and out of the war. Feeling an intense pull towards his superior officer, he is unable to save him from violence. Stunned and disoriented, as Whatling writes, “Reeves is amazed how all at once direction seems obvious, then suddenly non-existent.” The speaker of “Holy Ghost” feels similarly disconnected: “Father Morrell could look right through me like I was no longer there.” The parallel sensation of Thomas, the mentally ill protagonist of “Orange Lady,” is even more intense: “He walks faster as his arms detach and float away.” Perhaps most poignantly, the old woman in “Dog Cemetery” recalls, evoking a different kind of limbo, “They said I wouldn’t be a person if I did [marry a white man]. According to our law, if a Kanien’kehá:ka woman marries a white man, she’s no longer one of us.”

A third thread running through the stories is the nature of friendship, especially between boys and young men. Always viewed from the perspective of one of the two, these relationships are permeated with loss or yearning. In the first story, “Indian Land,” the protagonist, bitter about being forced to leave the reservation, turns to Donny for support, only to find that “Donny looks ahead, his face miserable, so unlike the way he usually is.” In the last story, some years later, Donny reappears, and for a short period the bond seems to revive, but quickly drains away: “he looks at me with eyes steady as the noon sun. He wants to say something, but instead he turns and goes inside.”

Similar relationships colour “Through the Woods” and “Holy Ghost,” but it is in three other stories where Whatling does most to give poignant resonance to the theme.

Most veiled and elusive is the way that Reeves, the protagonist in “And They Still Play War” is drawn to his superior officer—in the end, though, he is desolated and disorientated by their tragic separation. Almost in the opposite vein of narration is the boyhood friendship between Kevin, the bumptious narrator, and his sickly and timorous “best friend,” Tom Finn. Determined to bring some spark into Tom’s sheltered life, Kevin engineers “adventures,” sorties that turn sadly askew and only drive the boys apart. Oblivious of what the author indirectly makes clear to the reader, the saddened Kevin can only say to himself, “Tom Finn’s my best friend and I miss him.”

It is in “Thumbing My Way,” though, that the relationship between boys is most intense and most poignant because Whatling veils it in pure suggestion. Over the course of a summer the relationship between the 18-year-old host and his 14-year-old cousin turns from icy indifference to emotional intimacy. As the protagonist writes in recollection, “Jamie was my first crush.” How we are left to intuit what Jamie felt in return, though, is part of the affecting drive of the narrative: the uncomprehending narrator can only report what he understands—far less than what, the author suggests, Jamie is experiencing and what leads to the subsequent tragedy.

Narrative thrives on tension or conflict, of course. While Whatling is clearly most interested in propelling his stories through shades of internal tension, he also does a lot with bad guys. And “guys” is the operative word. Although it may be facile to use the term “toxic masculinity,” the brutal male behaviour the author records is… unsettling. “It’s only harassment if you hear them say no… and I’m hard… of hearing”: the coarse humour and complacent swagger of the office boss in “Empty Seat” exemplifies most repellently the kind of male bullying that the author repeatedly exposes. Zane, in “Thumbing My Way,” is similarly abhorrent: politically rightwing and verbally abusive, he is on the run west “because he ‘banged up’ his girlfriend and she’s been ‘nagging’ him to marry her.” The type is everywhere: two bar drunks in “Spanish Lessons” guffaw inanely and, and with sexual innuendo, verbally taunt a young woman; Rodriguez, a fellow soldier in “They Still Play War,” “only seems to talk about the girls he banged back in high school….” The guise can change slightly but the abusive behaviour is the same: the boy in “Freeman Tavern,” for example, suffers from his father and his “drunken, violent… slow-to-ignite, but explosive anger.”

In broader ways, too, Whatling writes from a position of deeply held societal values; they matter. The demented evangelist who rants in “Orange Lady,” like viciously judgemental Father Morrell in “Holy Ghost,” reveals to us as much as we want to know about intransigent ideologues. The oily bafflegab of the regime in “Americium’s New Flag” is merely a secular version of the same thing. This twisted utopia, illuminatingly, permits three—and only three—societal values: “Technology, Science, and Military.” Not much different, really, is the “beefy” oaf in “Spanish Lessons”: “He was probably in Commerce, and his ambition was to work for some multi-national and die from cirrhosis by fifty.” Societal values, for Whatling, really do matter.

The most inimical societal force in Whatling’s story worlds, though, is war. “I thought their war was the most horrendous thing in the world. They could all go to hell”: the speaker in “Thumbing My Way” says only most vehemently what this story develops most fully. The Vietnam War in particular becomes, in two separate stories, the darkest of dark forces. More than just a sociopolitical nightmare, the war is entangled in the emotional nightmares of three main characters.

Clearly, it would be a hardened reader indeed who did not feel the bleakness of the vision stirred into being by these stories. The irony, as it is with all skillful writing, is that the author’s deftness with the craft of fiction is as strangely humane and life-asserting as the stories themselves are… “unsettling.”

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at UVic and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, UVic, and finally Lester Pearson College in Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at Banff School of Fine Arts and UVic. He lives at Nanoose Bay. Visit his website here. [Editor’s note: Theo Dombrowski has written and illustrated several coastal walking and hiking guides, including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), and Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island (RMB, 2018, reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen), as well as When Baby Boomers Retire. He has reviewed books by Frank Wolf, George Zukerman, Robert Mackay, Genni Gunn, Eric Jamieson, Adrian Markle, and Tim Bowling, for BCR.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an online book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster