‘Realism laced with compassion’

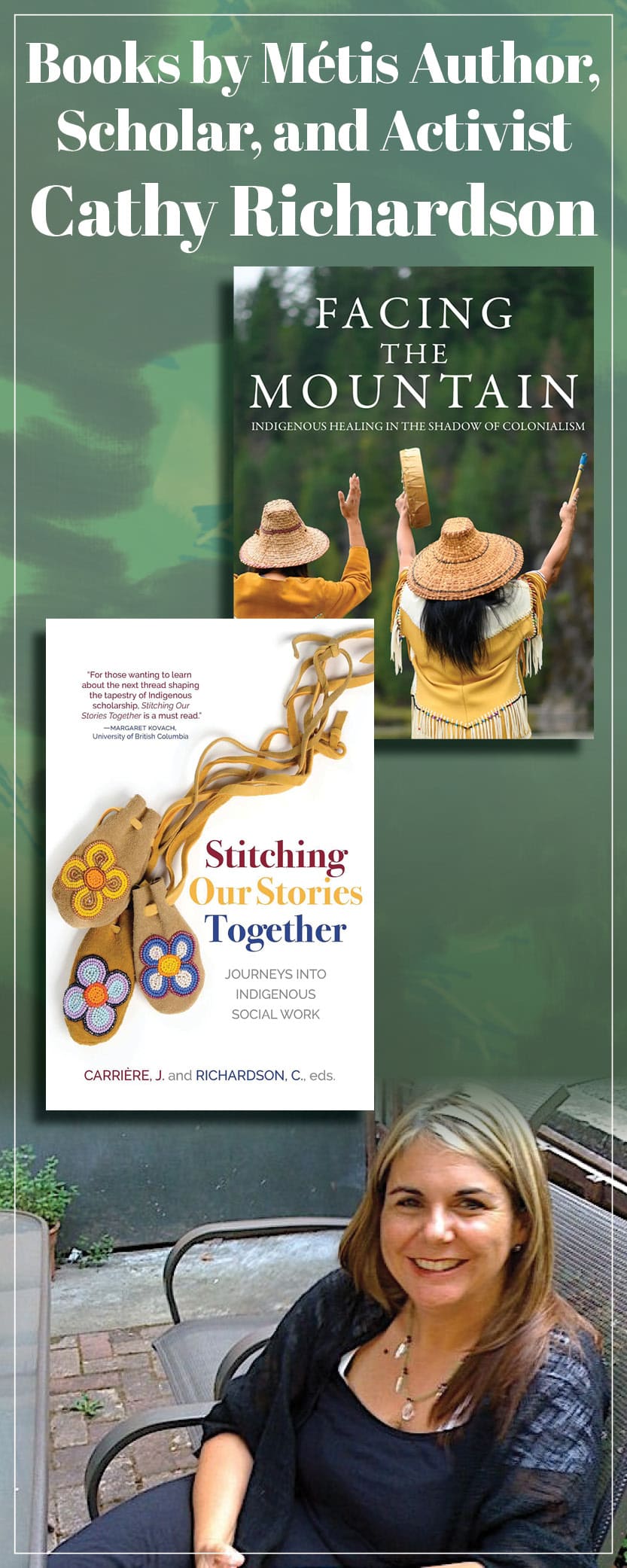

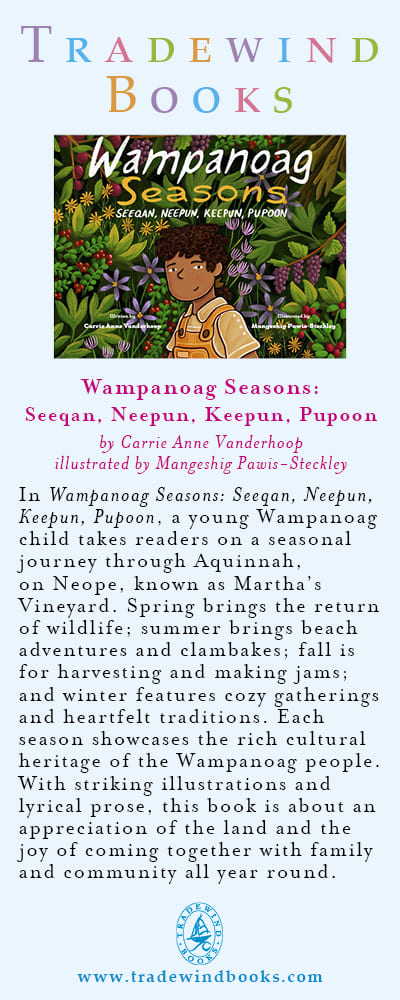

Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes: essays on motherhood

by Adrienne Gruber

Toronto: Book*hug Press, 2024

$23 / 9781771669030

Reviewed by Linda Rogers

*

Every human function is poetry, and poetry is about transformation, image into idea, idea into reality, back and forth, and that is why it is fascinating to notice how seldom poets render extreme transformation into poetry, or in this case, poetic prose. Could that be a function of the patriarchy, ewwww, disregarding discharge of human tissue, animate beings in the skins we inhabit.

Disgorging mouths and vaginas are finding voice in public discourse.

When I, as a young poet, ventured into the indecent terroir of mothering, my mother-in-law, a highly weaponised, intensely self-regarding lowlife critic, alumnae of the garden club and beneficiary of nannies, told me she had to hold her nose at the prospect of reading my poetry reeking the stench of blood and milk. She didn’t mention tears because there were stillbirths in there. Who would grieve the death of a child? Four actually. Mine.

This mid-century attitude does not deter Adrienne Gruber, who strides into the story of her life after birth wearing hip waders, ready to examine the phenomenal lives of Mothers and Other Mothers, both versions of the much-maligned female parent.

“While this era of medicating women to the point of erasing their memory is long over, there still seems to be a lack of full disclosure when it comes to birth.”

Wading is the operative word, because her birthing option was home delivery using, we presume, an inflatable pond full of love bugs from the microcosm to exit the blobs of flesh growing inside her, little girls, it turns out, swimming to the destiny foretold by the first sperm donor, “He for God and she for the God in him.”

Remembering she is a poet and learning she is the daughter of a scientist we expect clinical observation of pain and we are served that with unflinching candour. It ain’t all pretty, so look harder and what you see is the matrix of love and connection. Mother as nerve endings is the first canticle, a song if not of pure joy, at least of maternal endurance. Gruber writes of mental breakdown and pharmaceutical therapy, anxiety that lives in the one-celled animals that inform us of the fight or flight responses that govern our lives, whether we admit it or not. She loves the idea of motherhood, unconditional love, but the journey is harrowing, the gynecological/psychological equivalent of fingernails on blackboards, tearing the night sky apart. But, in the end, the blackboard embraces as it informs us that we are one in the many, stars burning bright.

This book is as much about the ease in dis/ease as it is about parenting, and Gruber does not flinch from what we need to know about the suffering of ourselves and others.

Observation of fractals leads to meltdown as congenital hypersensitivity manifests in acute anxiety. The mother eats sour grapes and the daughter’s teeth are on edge. “She beats her wings and there is a 6.4 earthquake in California.” Her imagery is gorgeous, pond life in a microscope, but it does jar the soul in its amplitude, so we are all, readers, and writer, mothers and daughters, in a crisis condition.

The conventional wisdom of earlier generations who embraced twilight birthing, so that the most glorious moments in human history were obliterated by opiates, might place a caveat on this book of unlies. Would first time femmes enceintes parse their swollen abdomen (hmm, a word from the patriarchy as if bellies, bosoms, and bums, all the beautiful B words are owned by the men in Amen) as a kinder alternative to parturition?

“After having kids,” she writes “bodily functions quickly became a kind of muse. My literary bread and butter.” And there are hungry mouths to feed.

Gruber, a glorious answer to the accusations of “too many nerve endings” explains her acute sensibilities in chapters devoted to sound and smell, the affliction of uber sensates, I was going to write “humans” but isn’t “smell” the first line of defence for all child-protecting mammals in the animal kingdom, hence “animals.” Are we not endowed vigilance so that our children survive the sad trajectory of war on ourselves and each other.

Gruber, a glorious answer to the accusations of “too many nerve endings” explains her acute sensibilities in chapters devoted to sound and smell, the affliction of uber sensates (I was going to write “humans” but isn’t “smell” the first line of defence for all child-protecting mammals in the animal kingdom, hence “animals”?) Are we not endowed vigilance so that our children survive the sad trajectory of war on ourselves and each other.

And who is the saint, the pillar of rectitude enduring sleepless nights interrupted by arbitration of the most important post-colonial matters before the people in her memoir? For most of the book, he is Dennis, the loving husband and dad who stands by his woman, a creator in the human and artistic sense, a sacred obligation.

As if we need to be told, a surprise maybe to some, but not this reader, from his first breath fluttering her heart and the pages of her book, Dennis is exquisitely Indigenous, sensitive to the source and resource of parenting, the unshakeable foundation and vulnerability of his culture ravaged by men raised in the homoerotic anti-familial culture of British boarding schools.

We love him before we properly know him as the embodiment of ancient values. He too suffers from traumatic genetic memory, his cortisone levels armed for battle. Just as he fiercely protects survivors in court, he spends sleepless nights defending his children from the anxieties that daily assail him, the knife edge of terror.

Gruber brings out her knife in self-defence against an unsympathetic reviewer, an unusually sharp poetic device. Usually, we ignore our critics. But this is a struggle for survival of the real story, so she resists, and with lethal eloquence.

I would tell her about an act of grace with the well-known writer I once described as an ice queen, an empathy avoider in her otherwise brilliant canon. And this, the woman who wrote the book on uncivil society, women with suppressed souls and sensibilities, also the daughter of an entomologist, forgave me saying the world needs naïve idealists.

Bring on realism laced with compassion.

Barricaded by high intelligence, humour, and fierce love, their three young daughters live in the theatre of joint defence. That is one definition of family. Her girls may be afflicted with monsters, martyrs, and marionettes, but in the end, they have an affirmation; the M word that matters, Mother, genetic memory all reproductive species from the smallest organisms have in common.

*

Canadian People’s Poet Linda Rogers is a writer with intense mother and aunty connections to the human family. Her current work includes a biography of Chief Tony Hunt and Hallelujah, The Cat Came Back! the plague memoirs of elder women. [Editor’s note: Linda has reviewed books by Peyman Vahabzadeh, Michael Elcock, Marion McKinnon Crook, Tim Schouls, Michelle Good, and Marilyn Bowering for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “‘Realism laced with compassion’”