‘A lifetime of striving’

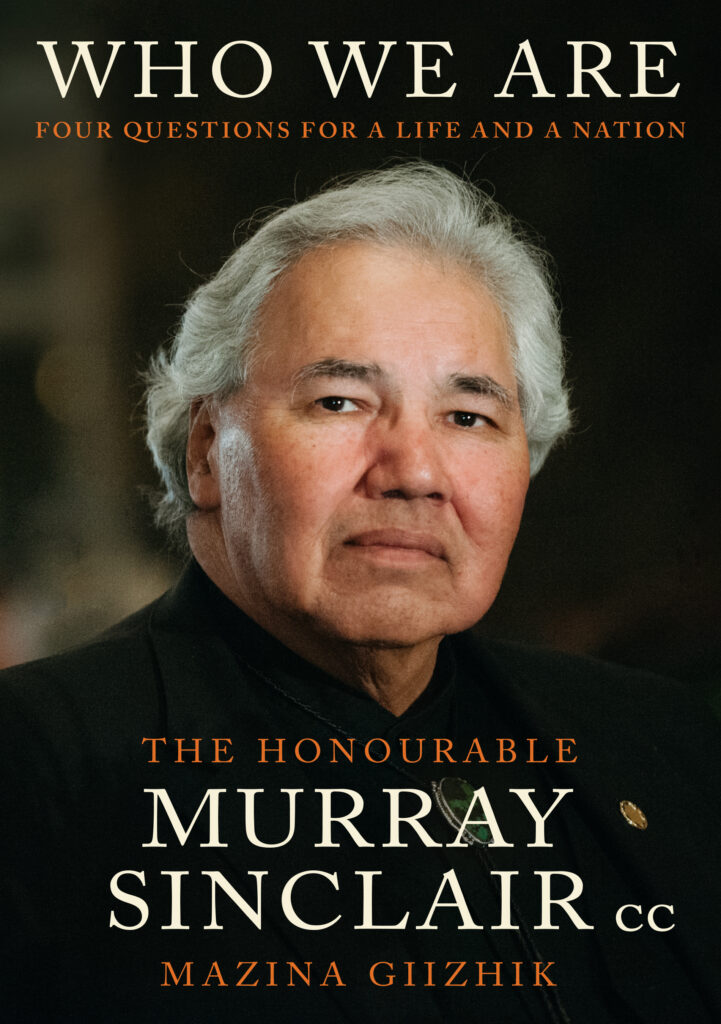

Who We Are: Four Questions for a Life and a Nation

by The Honourable Murray Sinclair CC, Mazina Giizhik (as told to Sara Sinclair and Niigaanwedom Sinclair)

Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2024

$29.95 / 9780771099106

Reviewed by Richard Butler

*

Who We Are: Four Questions for a Life and a Nation appeared only a couple of months before Murray Sinclair’s death on November 4, 2024 at the age of 73. That was probably for the best. The book is so intensely personal it would have been difficult to know what to say if you ran into Murray at a function or in the grocery store.

Who is this book for? And why does this review article about a person from Manitoba appear in a journal dedicated to British Columbia stories and authors? The short answer is that Murray’s lifetime contributions, whether personal, local or national, were for all Canadians, Indigenous or not, including all British Columbians. And so is this book. It has my highest possible recommendation.

Of course, I already knew about the public man, and had actually met Murray once, when he was presented with an honourary doctorate of laws from Thompson Rivers University. The breadth and depth of private insight and meaning conveyed by this book is quite overwhelming.

The book was largely drawn and edited from Murray’s reminiscences, as told to Sara Sinclair. That material was supplemented with stories and ideas shared with his son Niigaan, and from other sources. It begins with a commentary on residential schools and ends by including part of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission summary report. But it is so much more than that.

Despite the variety of sources, the book’s presentation is seamless and its style of prose is light and effortless to read. There are wonderful anecdotes, always to the point.

Like many other books in this genre, Murray’s stories speak of the victimization of Indigenous people. But Murray is nobody’s victim and by his example others may heal themselves and their loved ones from intergenerational trauma, just as he had.

Murray’s description of that healing process, full of humour, wisdom, and indictments, would be reason enough for you to read this book. But you can also gain, as I have, a first-hand sense of some of the more insidious causes of intergenerational trauma; why that trauma abides, just as surely as the depression, anxiety, rage and sense of worthlessness of mental illness abide; and how that trauma may in time be healed, both individually and collectively.

This book also gives a better understanding of why people call it a genocide, and has persuaded me—previously a genocide-skeptic—that the categories of genocide are not closed.

Read on if my thoughts in those respects may be of interest to you. Or simply get your hands on a copy of the book and experience its wonders directly for yourself.

Murray’s paternal grandfather was from northern Cree communities near the shore of Hudson’s Bay. His grandmother was a Saulteaux-Ojibwe and Anishinaabe but her family had become non-status. Murray tells of the two of them meeting up at the convent at Fort Alexander; marriage through arrangements made with the Mother Superior; and their return to a reserve near Selkirk for a life together.

Murray’s mother was from Fish River. His father’s family had enfranchised “so that they could remove their children from residential school.” His father enlisted in the Army and was deployed to France in late 1944. He returned wounded. The two married and had three children. His mother died soon afterward, which was overwhelming for his father. The young children were taken in and raised by the Sinclair grandparents and three “aunties” who lived with them.

It was a “very standard household for the time and location,” Murray tells us: a big log house on a small plot of land. The grandparents spoke mostly in English to the grandchildren. Granny cooked and sewed, while Grandpa earned most of the family’s money from trapping and seasonal work in the wage economy. “When the aunties were in the house, it was filled with laughter and joking.”

When their house on the St. Peter’s Reserve was falling apart, the family moved into Selkirk while Grandpa built them a new one. Living in town, Murray says, “was like moving to a foreign country.” In town was the first time Murray and his brother regularly played with white kids. The main difference, initially at least, was not with their playmates but in interacting with the parents:

It was clear from the second I met older people that they saw me and my brother as different, “dirty,” and disgusting. …. Older kids, mimicking no doubt what they heard from their parents, referred to us as “dirty Indians” and “stupid” and accused us of looking to steal what they had. We were told that our family was useless because we were poor and that the work our parents did was not as important as the work of their parents. ….

Soon enough, kids my age started to act like their parents and older siblings. By the time I entered grade one, I felt isolated from all the white kids in town, and it wasn’t just because they would not play with us. …. For years, I carried a sense of isolation and hurt because of these actions. I couldn’t understand why kids my age would do this.

After three or four years in Selkirk, the new house was finished and the family moved back to St. Peter’s Reserve. Murray attended the local primary school close to where they lived, and then a middle school for grades 6, 7, and 8.

Murray’s Granny and his aunties were always a moving force in Murray’s education. A very religious woman, Granny had made it clear early on that Murray was going to become a Catholic priest, even though Grandpa was Anglican. By the time Murray was 10, and had begun “living up to the badness” expected of boys his age, he was having second thoughts.

At 12, as a result of a surprise birthday present and the inspiration of his aunt Josephine, a teacher, Murray “fell victim to books.” He started high school in Selkirk where he excelled in sports and in the classroom. He was particularly interested in history, but noted the gaps in the version of Canadian history he was being taught.

I started to think of my life as one of failure and embarrassment… No one looked like me in the textbooks, and I learned that white people did everything that mattered. As a result I would tell myself lies in order to act like someone I wasn’t. I tried to mimic and emulate those around me who I thought were successful, even though I never looked like them and wasn’t accepted when I tried. This all led me to feel very uncertain, shy, awkward. I now know this to be shame.

Murray himself never went to residential school. Even so, the residential school his Granny had attended

taught her and everyone who went there …that if they tried to be Indian, they were going to hell[;] … that we were inferior, that we lacked a culture, we didn’t have a structure, we didn’t have a government, we didn’t really have any sense of property, so we didn’t own anything. And that we were servants to the white masters who came from Europe.

That was the gist of what was going on in Canada throughout my early lifetime. A lot of those ideas were reinforced by family members who had those messages driven into them at residential school. They drilled that into you at public school too. We were taught, and so grew up believing, that there was not anything proud about being Indigenous, about being an Indian; that, in fact, it was in our best interest to avoid identifying ourselves as Indians at all.

Reading Murray’s backstory provides non-Indigenous Canadians with a deeper understanding about what constituted the intergenerational trauma among Indigenous people through the years, trauma which continues in many individuals today. Yet it also shows us a more subtle aspect of that trauma. Murray’s Granny and aunties were, as he tells it, entirely capable and loving as parents. Naturally, they wanted what was best for the grandchildren, including success in mainstream Canada. The problem was that, in doing so, they unconsciously acquiesced in the narrative of worthlessness. In the result, the focus of Murray’s upbringing was that he had to turn himself into something better than an Indian, even though—as Murray says—Granny herself never forgot she was Anishinaabe.

At that time, Murray was also involved in Air Cadets. In the course of those experiences, Murray says, he realized “that I had been totally immersed in mainstream Canada, … raised in the belief that we were not Indigenous, that there were no longer any Indigenous peoples, and there was no point in looking.” On an Air Cadets exchange visit to Wales, Murray was asked what it was like being Indigenous and he couldn’t answer. As a result, he came home

want[ing] to know why I did not know the ways of my people, … why Canada did not know the ways of my people … [and] why Canada had all the land and Indians had these small places called reserves. I wanted to know why I could not speak the language of my grandmother, why I did not know the history and traditions of my people … and why my grandmother and so many others believed that, by not teaching me those things, she was saving my life.

Attaining meaningful success as an Indigenous person was a protracted and often painful process for Murray. He had to begin a re-learning:

I started to understand my lack of cultural knowledge more deeply as a progression of the pressures put upon Indigenous people to succeed in white society. Part of the propaganda that the education system had filled us with was that, if we didn’t succeed in settler society, we were failures.

He read about and worked directly with organizations and people seeking to restore a broad recognition of Indigenous worthfulness. His reading was “like waking me up from a sleep.” There were personal contacts with co-workers and Elders—a whole new kind of education. “Each person I met was like an entire Book of Knowledge,” he writes, alluding to the birthday gift he had received from Aunt Josephine, which she had made sure he read from cover to cover.

On one occasion, Murray tells us, he travelled to a day-long workshop to explain about constitutional repatriation and what the Constitution of Canada was all about. The community Elders had been lined up in a semi-circle at the front of the room. It became clear the Elders were going to speak first. And they did so, for the entire day. Murray was invited to a feast that evening and to come back the next day, and for two more days after that. The Elders told their story from the beginning of time. They talked and Murray listened. At the end, after he had given his response, the community member who had sat with Murray the whole time, translating for him and answering questions, told him the following:

We know that you came here to tell us about their constitution, that white man’s constitution, we know that that’s an important part of what’s going to happen in our future. But what we also believe is very important is that they need to understand our constitution. And now you have heard it.

*

From time to time, Murray had prescient dreams:

Many years later, after my grandparents had passed, I had another dream. In this dream, I was walking home in the dark. And I saw, way off in the distance, I saw a big, big flame, a big fire. I thought, there’s something down there. I had better go check this out. …. I started running towards it along this road. It was the same road that ran in front of my grandparents’ house. As I passed our house, I saw my grandmother and my grandfather standing in the front porch. My grandfather had his arm around my grandmother. And when she saw me, she started to cry.

She said, “I miss you. I want you to come … and be with me, I really miss you.” I was tempted to leave the road to be with her because I really loved my grandmother. But as I started to turn to do that, my grandfather, who was a very, very quiet man, he spoke to her in Cree and he said “No, mom, don’t call him off his trail. He has work to do. Those people down at that fire … [are] waiting for him. They need him. He has to help them first. Then he can come to you. We’re not going anywhere. We’re already where we need to be. He still has work to do.”

When Murray’s father died, and then his younger brother, Buddy, Murray was extremely hard hit. His memoir includes a remarkable poem about Buddy, which commences

If I but could

I would reach back

into your youth

and stop the movement

of the brutish hand

that hurt and left a scar

that lingers in you still …;

and which ends

But all that I can do I fear

Is listen to your words and tears

With heavy heart …

….

But nonetheless I promise you

that I will always … tell the world

that what you have revealed to me is true.

And I will sing your song each day

And tell the world in every way

That I think

You are the strongest

Most resilient

Bravest person

I have ever known.

These touching insights and affirmations are from the man who would eventually bring us the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report about the lives of Indigenous people generally. The parallels are unmistakable.

*

Murray went on to university. He thought he wanted to be a physical education teacher because sports were the one thing that had held him together during his high school years. But events intervened. He left university and worked at a friendship centre and elsewhere. He met people. He learned how to organize and influence. He joined the Manitoba Metis Federation and gradually assumed leadership roles. Murray tells the stories very well.

At age 25, he enrolled in law school. The hardest thing, he says now, “was memorizing racist ideas.” He was surprised by the number of people in the law school class who had no idea about treaty rights or about sovereignty. No doubt his professors were similarly surprised by their precocious student, able to convert a discussion of the St. Catherine’s Milling case from the issue of territoriality to the whole matter of Indigenous sovereignty. Eventually most professors realized they could escape Murray’s withering gaze by answering fully the questions he asked.

Murray graduated in 1979 and commenced articling. He tells a marvelous story about going to court and needing to look like a lawyer, needing to dress the part, and what happened when he turned up at a remand hearing wearing his brand new suit:

Judge: “So what’s this about?”

Murray: “Well, Fontaine, sir. You called Fontaine.”

Judge (looking at the papers in front of him): “Okay, Fontaine. So what are you charged with today, Fontaine.”

Still an Indian, no matter how well dressed. As fellow memorialist the late Harold Johnston once said, in one of his books reflecting on life as an Indigenous lawyer and activist, “Without humour, we’d all go crazy.”

Harold wrote about life in the law in those days in northern Saskatchewan. Both he and Murray convey some lightness but mainly the darkness of what their clients faced in dealing with Canadian justice. Both men set out to make a difference—Harold as a criminal defence lawyer and also a prosecutor, and Murray as counsel and advocate on constitutional issues and cases and advisor to Indigenous organizations.

Harold’s memoirs of his life in the law are increasingly imbued with searing anger, as he tells—for example—of young Indigenous men who happily went to jail because it would increase their status back home once they got out. Ultimately Harold came to feel that practising law was a dead end in his hopes to make life better for his communities. He went to his cabin and trapline north of La Ronge, and wrote the first of two profoundly important books about what it meant to be Indigenous in the face of the law during his life and times.1

Murray’s life in the law took a different path through those very difficult times. His own anger is there in the stories he tells, as for example about Pierre Trudeau and the 1969 White Paper proposals in relation to the Indian Act. That anger with Trudeau’s arrogance and ignorance is no less palpable than Harold’s anger against the justice system. But Murray’s anger is at a more abstract level, powerful but to me less heart-wrenching.

So Murray was able to stay in law, able to see a future role for himself in the fight for Indigenous justice. With some initial hesitancy, he allowed his name to be put forward for the position of Provincial Court judge.

Within weeks following his appointment, Murray became co-chair of an inquiry into the murder of prominent Indigenous leader J.J. Harper—labelled the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry. Following the model of Thomas Berger’s Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry from the early 1970s, Murray and his co-chair, Justice Al Hamilton, travelled extensively to northern communities.

Murray tells us that Hamilton had somehow never had an Indigenous client. His connection to Indigenous people was exclusively from what he had observed in court. He had never been on an Indian reserve in his life. Travelling with the commission was, Murray says, a real eye-opener for Hamilton.

Murray provides us with a series of delightful anecdotes, each with a clear message. Here is the first of them:

Every time we began a meeting with the community, the grannies would form a circle around me, and we would sit and chat. And of course, he saw that happening, and he didn’t participate with me in that kind of a thing. But he often privately emphasized the fact that he was very meticulous about starting on time. He wanted us to start on time so we could finish on time. And when he saw the kind of laid-back approach that I was taking to starting and making sure that I visited appropriately before we started I don’t think he quite knew how to handle that.

Of course, he learned that that was not just my way of doing things but it was also the communities’; that we needed to feel that we were part of them, and so he kind of warmed to that practice in time.

Murray tells us more about the Elders’ ways of doing things—about monthly community gatherings which were not only about what was going on at the moment but also a “process of historical transmission … by which the children had a better sense of who they were.”

After the commission had released its report, Murray was asked by the National Justice Institute to develop a course on what it is like to be a judge in communities such as the commission had visited. One example of what he taught was culturally sensitive oaths. Another was about allowing Elders to testify collectively, as opposed to singularly, as the means to convey collective memory. That was counter-intuitive to the common law methods of finding facts. Murray then tells us more about his own experiences as a judge in the north, replete with stories containing similar insights.

*

All of the foregoing sets the stage for the next part of the book, which is about what has mattered most to Murray in his life and what matters most going forward.

It starts with his children, Niigann and Dene and Gazheek, and their children, and the promises he made them about understanding Indigenous identity. It is about what he learned from his own family about being a father, and about his own evolving relationships with his own father. It is about balancing his expanding public life with his private, family life, and how with the help of Elders and family he got through it.

Then Murray shares with us some inter-personal aspects of the TRC process, making it a testimony to healing. It was about eliciting truths and listening to them. Murrray says the TRC was initially not aligned with what he intended it to be—an opportunity to engage not just with a few but with all survivors in Canada. And so they did.

Murray says he didn’t reflect on his own experience of witnessing until after the TRC process was all finished. He says the hardest part is he can’t stop thinking about it. “My concern is that if I start crying about what I’ve heard, I’ll never stop.”

Murray goes on to say he struggled with how to bring survivors’ voices into this book. But here, it seems to me, lies the greatest success of the book—using his own story as a survivor to point out the sources of the problem. “People think reconciliation is sometime in the future,” he says, “but I say reconciliation is in the past.”

What Murray survived was the result of generations of Indigenous people being told, at every turn and in every possible way, that they were worthless because they were Indian. They simply had to become something else.

That was the unrelenting message of the pre-Confederation Bagot report. It was the whole fabric of the government’s subsequent assimilation policies which gave us the Indian Act, the reserve system, the potlatch ban, and yes the residential schools. It was the message of church missionizing. It was the message of resource extraction companies in British Columbia, who hired and benefited from Indigenous workers when labour was short, but laid them off as soon as non-Indigenous workers again became available, citing the “lazy Indian” trope. It was the message of racializing laws. It was most profoundly the message of mainstream child protection agencies and the justice and health care and education systems—the “drunken Indian” trope, the “dumb Indian” trope.

What Murray survived was an ongoing intentionally-imposed sickness unto death for Indigenous people. It was a psychological genocide every bit as fatal to subsequent generations as the machetes of the Rwandan Hutu have been to their Tutsi brethren. It was genocide in slow motion, as if from the fallout from nuclear weapons.

One may legitimately be skeptical that the kinds of literal genocide defined in the UN Convention took place through Canada’s residential school system. There were no mass killings, no mass forced removals of children. Most important, there is no evidence of literal genocidal intent in those or any other respects.

However, once we accept that the categories of genocide are not closed, and that not every genocide takes the same approach to accomplish its ends, there is no difficulty finding genocidal intent in the policies and conduct of our governments, churches, corporations and, by acquiescence, members of Canadian society at large in our treatment of Indigenous peoples.

Murray’s own survival is the hallmark of his life and this book, as well as the legacy he leaves for his own children and for the future of Canada. His point is most powerfully expressed in the poem which closes this part of the book. Here are some excerpts:

… For our right to be

Was told in our Creation story

And all such teachings always held us true.

And then those others came

And with their twisted thoughts and words and tongues

Declared that all [our Creator’s] work with us was false

And that our sense of Him was wrong.

They made us deeply sick with growing doubt

As, slowly, harshly,

Like a rising tide

They drowned or drove away our spirit

Piece by piece

Child by child,

So that when we woke one dark and lonely day

We found

Our spirit and our faith had shriveled and were gone.

….

They took us off our spirit road

And tried to make us walk inside their shoes,

But when we looked behind

We could not see

The point from which our journey had begun,

And when we looked ahead

We could not hear

The voices of our mothers calling out

Nor see the light of fires

Showing our way home.

We were confused and felt like we were lost.

And so

Our spirits ran away and hid

In places dark and safe

So they would be protected

Strong and pure, ready to embrace and be embraced

When it was time.

*

The final part of this remarkable book looks forward and gives guidance from a lifetime of lessons learned—guidance to his children and grandchildren and to all Canadians:

My memoir was intended to be a learning experience, by sharing my own personal growth and the potential it has for the growth of others. I intend it be a lived learning experience for other people in my situation: this is what I experienced, and this is how I felt, and take from this what you will. Because that is how to learn. That’s how the Elders teach us. Now it’s up to you to figure it out.

“My children are my most important legacy,” Murray writes, because children reflect who we are, what we have done, our sense of purpose and whether we will fulfill that.

That spirit and ongoing challenge are best expressed in the final verses of the poem just quoted:

But now that we are finally freed

Of heavy chains of aging pain, many go in hungry search

Of spirits so long hidden, almost lost,

And there is great rejoicing

In connections strongly made.

But sadly some have found

Their spirits have been locked away,

So well and for so long

That they can not be found.

Murray’s own lifetime of striving may be at its end, but the message of this book is that there’s both hope in our children and still a lot more work to do.

*

Richard Butler lives on the traditional territory of the lekwungen-speaking Peoples, a retired lawyer and sometime law professor, and more recently a writer on various Indigenous subjects. He is the author of Taking Reconciliation Personally, I Dare Say… Conversations with Indigeneity, and the new title What Is This? Who Am I?: Culturally Informed Appreciation of Coastal Peoples’ Artworks, published through A & R Publishing. [Editor’s Note: Richard Butler recently wrote the essay An Exercise in Futility and has reviewed books by the Reverend Al Tysick, John Borrows & Kent McNeil (eds.), Karen Duffek, Bill McLennan, Jordan Wilson (eds.), C.P. Champion and Tom Flanagan (eds.), and Aaron A.M. Ross for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

- Harold R. Johnson, Peace and Good Order: the Case for Indigenous Justice in Canada, McLelland & Ste0eart, 2019, 2023;The Power of Story: on Truth, the Trickster and New Fictions for a New Era, Biblioasis 2022. ↩︎

2 comments on “‘A lifetime of striving’”

I would like to make an ongoing contribution to the process and dialogue that Murray Sinclair gave his heart and understanding to. I first encountered Murray Sinclair when I attended the University of Alberta, attended classes and began a Masters Thesis in the Department of Human Ecology based on a Native Life Skills program I attended at Stan Daniel’s. More to cone

Thanks for your comment, Lyn. What would you like to tell us about Murray Sinclair?