The symbiosis of fish and human

Travels Up the Creek: a biologist’s search for a paddle

by Lorne Fitch

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2024

$25 / 9781771607131

Reviewed by DC Reid

[Editor’s Note: Although the subject matter of the book and its review pertains to Alberta, the issues discussed within this title do have validity over the provincial border in regards to how British Columbia’s waterways are affected by industry.]

*

Lorne Fitch has been a long-term biologist, studying plants and animals in Alberta, including several species of fish. Travels Up the Creek is a historical look at how the land and water has evolved in the 20th century. The fish species include Westslope cutthroat trout, bull trout, grayling, mountain whitefish and suckers. Residents have long lobbied for rainbow trout stocking and the water bodies bear lots of this species as well.

Fitch has worked his forty-year career both outside of government and within, or, in opposition to bureaucrats as business plans repeatedly call for assessments of the areas intended for development as the positive thing seen by developers and government. For example, Alberta is the leading oil producer in Canada and its plans reflect that commercial option, along with other industries, logging among them.

His view is: “What trout need to survive are stream habitats that are cold, clean, connected and contain complex elements. The presence and abundance of trout populations is a metric of watershed health and a report card on the way we manage land use in a watershed.”

Over the years, different plans have been tried. The area close to bodies of water is called the riparian zone. Efforts by the people and the Cows and Fish Riparian Management Society, have paved a way to improvement, where creeks interact with road, construction, and industrial sites.

One of the important animals in this process are beavers: they build dams that hold fish. But there are also grasslands that need work. They provide the basis for plant-eating animals like the resident pronghorn antelope, elk, deer, and other species. One very positive fact in Alberta territory is that almost 60 percent of the land is public, and thus can be fostered to support wildlife and plants. Private ownership is 30% and 10% is federal.

The public has said they want to help, and the Cows and Fish group has given them plans to do just that. Beaver dams seem, on the surface, simple structures of logs, sticks and mud. “What is concealed is a time-tested pattern of controlled leakage, energy dissipation and groundwater recharge.” Where beavers have moved on, they can be persuaded to come back. Humans build rough structures and the beavers improve them, and their numbers grow. There is no point coming in with concrete, lead pipe, and culverts because it isn’t natural and does not result in environments that animals and fish would survive in.

Large boulders, as an alternative, were put in streams to create calm water for fish, but these soon created holes that sunk the boulders out of sight. So, beavers are better. And mimicking their work with logs, and root wads, log walls to restore stream banks worked the natural way by fostering the growth of natural trees like aspen and willow. Natural sweetgrass does one better, as it can be used in ceremonial, medicinal, hygienic, utilitarian, and inspirational ways.

Many animals depend on beavers: bison, moose, elk, caribou, deer, antelope, muskoxen, mountain sheep, and goat are the on-land species that have survived to present times. There were lots in the past: between 30 and 60 million antelope in the early 19th century. Hunters brought their numbers in North America to 13,000, though their number increased to nearly 1 million before being in steep decline presently. And beavers have worked at saving water for 10 million years. This makes it flow around the calendar down into rivers to benefit man and the plants and animals on their shores.

Sediment has been washed out of the land and downstream. Where it ends up, it forms a thick mud that sticks gravel to the bottom and makes fish-spawning redds much reduced in number. This has reduced grayling and cutthroat to shadows of their former numbers. In 1903 their numbers were so great that two anglers caught 400 cutthroat from Fish Creek south of Calgary in one day. I happened to live on the cliff over Fish Creek in the ‘60s and ‘70s and while I always caught fish in Fish Creek, and the numbers of my fish were well in excess of all other anglers, it was a few per day for me and my mother ate a lot of trout.

Fitch sums up needed streams this way: “Straightening and straitjacketing the channel and covering the flood plain with roads, buildings and parking lots compounds problems of flooding. Intact flood plains absorb and store flood water, dissipate energy, reduce erosion and add to groundwater storage, invaluable for future thirsty times.”

The result is: “a cacophony of birdsong, abundant other wildlife and a pleasant cool space for us to escape the summer sun.” So, we are part of the equation of need. And if fish can’t live in a stream we don’t do as well ourselves.

But enter business. “Today’s commercial logging is brutal, mechanized, large scale and probably economically marginal. To make economic sense the usual rules about land use are consistently watered down by the Alberta Forest Service as a sop, perhaps subsidy, to the timber industry.”

Industry and government are a generation behind the Alberta public who now see the need for leaving land and water and restoring it as well. However: “Whatever the public process is, the deal is rigged, and participants end up wasting time and energy on something our Forest Service and the industry were really never engaged in anyway.” In other words, the public has seen the need to make changes itself.

The problem is that once a wild animal has been wiped out, it creates a void that cannot be refilled. Industry says it follows all the rules and regulations, but they lobby to reduce the effect the rules and regulation have on their bottom lines. Fitch goes on to say, with his long experience, that even if that were true, the Forest Service that is supposed to be impartial, is, in his words, “a captured agency.”

“Despite our being awash, often up to our hips and higher, in a flood of plans, policies, codes of practice, strategies, bylaws and legislation, paradise continues to be eroded.” There are the ongoing problems of shifting baselines, as each successive group thinks that what it came into is where it has always been, which is not true. That is why it is called a shifting baseline. An example is the dwindling of lake whitefish, which fishing made collapse in 1878. Yes, that long ago.

Fitch points out that one of the smallest of birds, the chickadee, is “no city wimp.” These hardy souls must eat a third of their body weight each day to survive the long, cold winter night. And all winter long. If we humans were in the same, er, boat, we would lose nine kilograms each night.

Biologists introduced “combat biology.” Without their hard work, the Whaleback area, would now be: “an industrial site with multiple roads, well sites, compressor stations, pipelines, the rotten-egg stench of sour gas emissions, constant truck traffic, power lines, weeds, sediment – and no elk.” The Nature Conservancy mounted a huge campaign to raise funds which were then used to buy back the mineral rights of Amoco, thus creating a protected area, perhaps for all of time. So, success, but lots of hard work.

Another example is an industry that fixed its eyes on an open grassland and proposed a wind farm. With its eye only on the bottom line, it took biologists and the public to make the natural world continue as before. “The pro-development faction will hate you for rocking the boat and the environmental community will criticize you [biologists] for not rocking it more. It is virtually impossible to find stable middle ground.” And the war goes on, with government in the back pocket of industry, and their biologists expected to sign off in favour of development, even if the data shows the opposite conclusion. In other words, impartial data are anything but.

For example, cutthroat trout are now absent from 94% of their historical range. But people, the Cows and Fish group, and biologists are fighting back. Fitch writes:

The cow parsnip patch is a pasture for grizzlies. The huckleberry patch isn’t just a sweet treat – it is a triumph of botany over frost, aided by pollinators and enough accumulated heat units from the sun. Mariposa lily, Indian paintbrush and fireweed tell a story of niches, needs, relationships and season. Beauty, in the natural world and maybe elsewhere too, lies in the details. The tapestry that is the landscape is a weave of stories, some evident, others less so. Mostly, though, it is about humility and respect.

It took 12,000 years of rough fescue growth to give Albertans the black soils that sparked the development of the province and sustain agriculture. Now it has been designated as Provincial Grass because of its importance. Things are going, slowly, in the right direction. Thank you, Lorne Fitch, for recognizing these things.

*

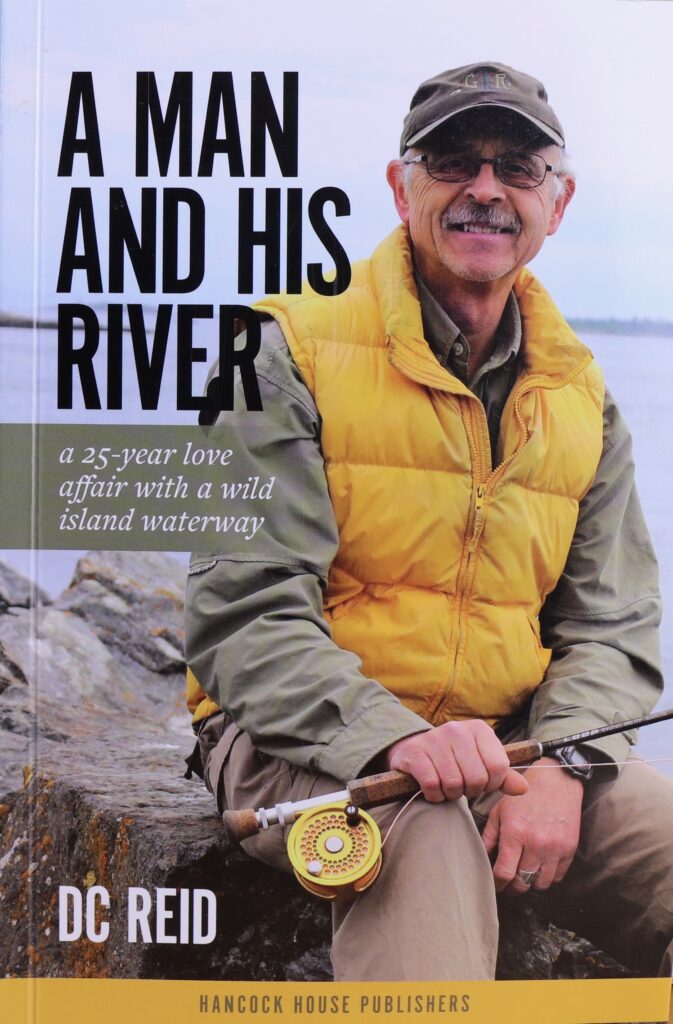

DC Reid is an author and a steadfast advocate for the Canadian literary community, having served as the president for the Federation of BC Writers, Victoria Book Prize Society, and League of Canadian Poets. He has won more than twenty awards for his work, including the 2023 Professional Outdoor Media Association of Canada gold medal for books for his memoir A Man and His River: a 25-year love affair with a wild island waterway. [Editor’s Note: DC Reid recently reviewed a recent title by George Bumann for The British Columbia Review.]

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster