When wild creatures know you…

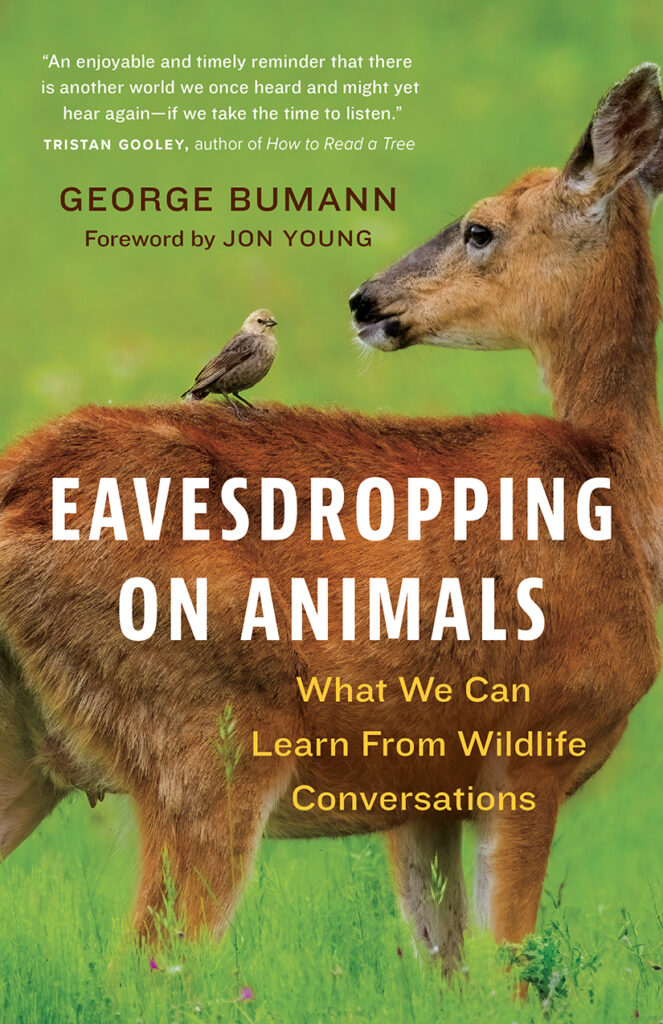

Eavesdropping on Animals: What We Can Learn From Wildlife Conversations

by George Bumann

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2024

$34 / 9781778400209

Reviewed by DC Reid

*

Fascinating is the only word to describe this book by wildlife ecologist George Bumann. It tells you how to insert yourself into the natural world and have conversations with all the animals with whom you contact. This includes birds, mammals, bugs, and specifically, coyotes, wolves, mountain lions, gophers, raccoons, rats, a good twenty species of birds and all the rest. The upper limit is up to you: to go out and find the animals, including fish, with whom you would wish to talk. Any animal is approachable in the ways described in this book.

The gist of the process is to make animals calm down around you and then interact with you in an entirely new way. From the ‘dawn chorus’ of all animals bellowing out their calls which we seldom hear as we lie half asleep in our beds. Even with eagles miles away, you can become friendly by using the techniques in this book.

Shauna is a wolf worker with Mission Wolf sanctuary. After being away for a while her wolves started calling for her when she was still in her car a mile away. And in fact, on a missed return flight, 400 miles away, the wolves began their calls. And they don’t forget a friend and keep the memory in their minds for people who have been away for ten or twelve years. Hard to believe?

Yes, but there is far more in this fascinating book. You must buy this book and learn to be inserted into the animal lives of this world. The gist of it is that if you pay attention to the animals around you, look at them, stand with your hands on your hips, you’ll scare the be’jesus out of them. But if, instead, you stand calmly, feet not pointing at the animal and don’t specifically eyeball them, you are en route to being their good friends.

And, it turns out, wild animals have words for the animals around them, for example, wild turkeys in the USA have many calls for snakes, specifically for poisonous ones. For example, rattlesnakes, copper heads, and if you are tuned in, you can expect to have 100 percent certainty that they are warning you, or simply telling you it’s a rat snake or even a box turtle Their calls are that specific. And wild turkeys have over 100 specific calls for things. You have to learn.

But first you have to become friends with the animals before they will talk to you. And did you know there are various human diseases that make it easier. For example, autism, colour blindness, full blindness and dyslexia, among others. Autism may make it easier because those who have it think in images not language: animals think in images, sounds, and smells. Many well-known thinkers were autistic: Albert Einstein, Michelangelo, and Mozart for example. And all animals smell, for example, foxes smell of burnt fried eggs, and cowbirds smell like fresh baked cookies. And humans may have as many as 54 senses not just five, or a sixth sense. And if you move with the sounds you hear, you feel it all over. Woodpeckers echo throughout our flesh and bones.

Ravens form flocks to harangue people. They call from high trees, not on the ground in front of you, so they are safe. Wolves talk to one another from as much as 10 miles away.

Spiders floating on a single thread of web travel as much as 25 or 30 miles, and were the only creatures found by scientists on the island of Krakatoa in 1883 after the volcanic explosion. Animals from small to large have lots of knowledge. For example, Bumann writes: “Making a living in the wild is not child’s play, and without a trove of learned and inherited knowledge, animals wouldn’t know where to sleep, where to get a drink, who to trust, and who to avoid, and would probably end up being someone else’s lunch.” So, wild things have lots of knowledge and how to use it. In other words, nature’s creatures are far more intelligent than we give them credit for.

Humans, though we can’t detect them, have distinctive smells. For example, we exfoliate 200 million skin cells per hour all day and night long. And this is how animals find us, for example, mosquitos. Dogs, wolves and so on can actually follow a person walking through the woods exactly on course, though that person can’t smell themselves. Search and rescue dogs go right for us when lost in the woods, and can follow scents as little as one part per trillion, the equivalent of a teaspoon of sugar in two Olympic-sized pools. Dax the dog found a five-thousand-year-old bone under14 inches of soil. Human technology can’t get anywhere close.

“Elephants decode long-distance, low frequency vibrations through their feet,” writes Bumann. Certain birds can see the Earth’s weak magnetic field for navigation. Mice croon to sweethearts in ultrasonic frequencies. Every species has its own special powers and memories. They even get to know specific humans, dozens of them. And elephants in Africa get to know humans by age, sex, and even tribal affiliation, as well as which ones mean danger.

If you are a good neighbour, word will undoubtedly spread. Grizzlies get to know vehicles by their licence plates and walk in front of them many times over the years, if they belong to humans they like, and with successive groups of cubs. But frighten the smallest of them and you frighten all of them. And if you record and then play a chickadee cursing a hawk, the alarm bell’s toll spreads across entire square kilometers within seconds.

And if you take care to understand the various calls, you can, for instance, tell if there is a fox or wolf coming your way, and to avoid it. On the other hand, mice gravitate to humans to find safety and resources. Many animals move together, such as chickadees, titmice, nuthatches and brown creepers in winter. This gives all of them, listening to each other, greater security and better feeding opportunities.

So, how do you get to be friends with animals? Well, standing with hands on your hips and looking directly at animals, scares the hell out of them. But stand or sit easily, looking away from animals, but with the corner of your eye glancing their way, relaxes them and they understand you are not there to frighten them. Over time doing the same thing with the same animal, or groups, such as nuthatches, makes them relax, and their language is so specific they will tell you of an owl-killed rabbit, etc. They have calls for tall people, small people, ones wearing green shirts, and other specifics. Animals are so acute they even recognize members of the same human family, even though they may never have met them.

“Wolves are attracted to people who are aware of their surroundings, and they are unsettled by those stuck in tunnel vision.” And sentinel behaviour is widely spread, with, for example, herring gulls and bald eagles selecting the highest spot to sit as a perch. It is a state of alarm.

How do you get to be friends? Try sitting under the same tree for a year, or even once per week, for half an hour. You will get to know all the animals and birds in the area, and over time will realize when their language shifts from loud calls of alarm to softer tones as they get to know you. But complete silence is a behaviour of alarm as well. So, listen, you will be able to hear for several miles and areas of silence or calls signalling danger.

If you fall into an animal, say you’re sorry and this silence, or reverence is interpreted as not being a threat. Repeated non-threatening behaviour makes them calm down around you. But large carnivores would move from a space of silence to the next space of silence to disguise its presence. If you disturb an animal, say you are sorry in soft tones. Sit in silent spots, the animals will notice that you are just like them. Avoid eye contact and body language of dominance. The quicker you pay attention to their sounds of fear, the more quickly you can establish a relationship of give and take. Slow down to the pace of nature. Be composed of your senses and surroundings.

So, what can a really smart animal do? Well, Clever Hans, a horse from Europe was a Russian trotting horse who had the rare ability to do math, tell time and spell words. He was a sensation and drew crowds of thousands. “Letting go serves to attenuate the divide between our inner and outer spheres and bring them closer together – this is where you will find your sincerest comfort and greatest strength.” Learn to let go. As it serves to attenuate the divide between our inner and outer spheres and brings them closer together – where you will find your sincerest comfort and greatest strength.” And this is the pace and wavelength that the rest of nature operates on.

“The response we get from these untamed companions is a gentle reminder to relax, drop our troubles, jettison the ego, and find our own better nature” advises Bumann. Another way into the world of animals is to come up with names for them, and after awhile individuals will begin to respond to their names, even if they are in a herd of animals. Say their name and they will come to you.

How close you can get is one of the deserving triumphs of this book. A female deer became so attached to her human partner that she led him into the private safe spot where she had stashed her newborn fawns so that he could see them. Such trust, such attachment. I’d love to have that happen to me in the wilderness, which is my favourite place. As I wrote earlier: fascinating.

*

DC Reid is an author and a steadfast advocate for the Canadian literary community, having served as the president for the Federation of BC Writers, Victoria Book Prize Society, and League of Canadian Poets. He has won more than twenty awards for his work, including the 2023 Professional Outdoor Media Association of Canada gold medal for books for his memoir A Man and His River: a 25-year love affair with a wild island waterway.

*

The British Columbia Review

Interim Editors, 2023-26: Trevor Marc Hughes (non-fiction), Brett Josef Grubisic (fiction)

Publisher: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line book review and journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board now consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Barry Gough, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. The British Columbia Review was founded in 2016 by Richard Mackie and Alan Twigg.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “When wild creatures know you…”